Klotho is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the KL gene. [5] The three subfamilies of klotho are α-klotho, β-klotho, and γ-klotho. [6] α-klotho activates FGF23, and β-klotho activates FGF19 and FGF21. [7] When the subfamily is not specified, the word "klotho" typically refers to the α-klotho subfamily, because α-klotho was discovered before the other members. [8] [7]

α-klotho is highly expressed in the brain, liver and kidney. [9] β-klotho is predominantly expressed in the liver. [10] [9] γ-klotho is expressed in the skin. [9]

Klotho can exist in a membrane-bound form or a (hormonal) soluble, circulating form. [11] Proteases can convert the membrane-bound form into the circulating form. [12]

The KL gene encodes a type-I single-pass transmembrane protein [7] that is related to β-glucuronidases. Reduced production of this protein has been observed in patients with chronic kidney failure (CKF), and this may be one of the factors underlying degenerative processes (e.g., arteriosclerosis, osteoporosis, and skin atrophy) seen in CKF. Mutations within the family have been associated with ageing, bone loss and alcohol consumption. [13] [14] Transgenic mice that overexpress Klotho live longer than wild-type mice. [15]

Structure

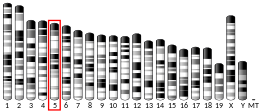

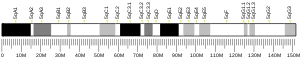

The α-klotho gene is located on chromosome 13, and is translated into a single-pass integral membrane protein. [9] The intracellular portion of the α-klotho protein is short (11 amino acids), whereas the extracellular portion is long (980 amino acids). [9] The transmembrane portion is also comparatively short (21 amino acids). [9] The extracellular portion contains two repeat sequences, termed the KL1 (about 450 amino acids) and KL2 (about 430 amino acids) domains. [9] [7] In the kidney and the choroid plexus of the brain, the transmembrane protein can be proteolytically cleaved to produce a 130- Kilo- Dalton, soluble form of α-klotho protein, released into the circulation and cerebrospinal fluid, respectively. [9] In humans, the secreted form of klotho is more dominant than the membrane form. [16]

The β-Klotho gene is located on chromosome 4. The protein shares homology (43.1% identity and 60.1% similarity) with α-klotho. [17] It should not be confused with the alpha-cut and beta-cut of alpha-klotho, which releases KL1+KL2 and KL2 domain, respectively.

Function

Klotho is a transmembrane protein that, in addition to other effects, provides some control over the sensitivity of the organism to insulin and appears to be involved in ageing. Its discovery was documented in 1997 by Makoto Kuro-o et al. [18] The name of the gene comes from Klotho or Clotho, one of the Moirai, or Fates, in Greek mythology, who spins the thread of human life. [7]

The klotho protein is a novel β-glucuronidase ( EC number 3.2.1.31) capable of hydrolyzing steroid β-glucuronides. Genetic variants in KLOTHO have been associated with human aging, [19] and klotho protein has been shown to be a circulating factor detectable in serum that declines with age. [20]

The binding of the endocrine fibroblast growth factors (FGF's, viz., FGF19 and FGF21) to their fibroblast growth factor receptors, is promoted via their interactions as co-receptors with β-klotho. [21] [22] [16] [7] Loss of β-Klotho abolishes all effects of FGF21. [23]

α-klotho, which binds to the endocrine FGF FGF23 changes cellular calcium homeostasis, by both increasing the expression and activity of TRPV5 (decreasing phosphate reabsorption in the kidney) and decreasing that of TRPC6 (decreasing phosphate absorption from the intestine). [24] α-klotho increases kidney calcium reabsorption by stabilizing TPRV5. [25] About 95% to 98% of Ca2+ filtered from the blood by the kidney is normally reabsorbed by the kidney's renal tubule, which is mediated by TRPV5. [26]

Clinical significance

α-klotho can suppress oxidative stress and inflammation, thereby reducing endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. [8] Blood plasma α-klotho is increased by aerobic exercise, thereby reducing endothelial dysfunction. [27]

β-klotho activation of FGF21 protein has a protective effect on heart muscle cells. [28] Obesity is characterized by FGF21 resistance, believed to be caused by the inhibition of β-klotho by the inflammatory cell signalling protein ( cytokine) tumor necrosis factor alpha, [28] but there is evidence against this mechanism. [16]

Klotho is required for oligodendrocyte maturation, myelin integrity, and can protect neurons from toxic effects. [29] Mice deficient in klotho have a reduced number of synapses and cognitive deficits, whereas mice overexpressing klotho have enhanced learning and memory. [30] Research with injections of klotho in primates demonstrates a positive effect on memory that lasts for as long as two weeks. [31]

Reduced klotho expression is seen in the lung macrophages of smokers. [32] An abnormal form of autophagy associated with reduced expression of klotho is linked to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. [32] (Although normal autophagy helps maintain muscle, excessive autophagy causes loss of muscle mass. [32])

It has been found that the decreased klotho expression may be due to DNA hypermethylation, which may have been induced by the overexpression of DNMT3a. [33] Klotho may be a reliable gene for early detection of methylation changes in oral tissues, and can be used as a target for therapeutic modification in oral cancer during the early stages.

Klotho-deficient mice manifest a syndrome resembling accelerated human ageing and display extensive and accelerated arteriosclerosis. Additionally, they exhibit impaired endothelium dependent vasodilation and impaired angiogenesis, suggesting that klotho protein may protect the cardiovascular system through endothelium-derived nitric oxide production. [16]

Klotho could play a protective role in Alzheimer's disease patients. [34] [35]

Research with injections of α-klotho in primates suggests a positive effect on memory that could have implications for research with humans. [31] Interestingly the cognitive effects in rhesus monkeys were observed even with subcutaneous injection despite previous results showing that klotho protein fails to cross the blood–brain barrier. [36]

Effects on aging

Reduced α-klotho or FGF23 can result in impaired phosphate excretion from the kidney, leading to hyperphosphatemia. [7] In mice, this leads to a phenotype characteristic of premature aging, which can be mitigated by feeding the mice a low phosphate diet. [7]

The plasma (soluble) form of α-klotho is most easily measured, and has been shown to decrease after 40 years of age in humans. [37] Lower plasma levels of α-klotho in older adults is associated with increased frailty and all-cause mortality. [37] Physical activity has been shown to increase plasma α-klotho. [37]

Mice lacking either fibroblast growth factor 23 or the α-klotho enzyme display premature aging due to hyperphosphatemia. [24] Many of these symptoms can be alleviated by feeding the mice a low phosphate diet. [7]

Although the majority of research has explored klotho's absence, it was demonstrated that klotho over-expression in mice extended their average life span between 19% and 31% compared to normal mice. [15] In addition, variations in the Klotho gene (SNP Rs9536314) are associated with both life extension and increased cognition in human populations and mice, but only if the gene expression was heterozygous, not homozygous. [38] [9] The cognitive benefits of α-klotho are primarily seen late in life. [9]

Klotho increases membrane expression of the inward rectifier ATP-dependent potassium channel ROMK. [24] Klotho-deficient mice show increased production of vitamin D, and altered mineral-ion homeostasis is suggested to cause premature aging‑like phenotypes, because reduced vitamin D activity from dietary restriction reverses the premature aging‑like phenotypes and prolongs survival in these mutants. These results suggest that aging‑like phenotypes were due to klotho-associated vitamin D metabolic abnormalities (hypervitaminosis). [39] [40] [41] [42]

Klotho is an antagonist of the Wnt signaling pathway, and chronic Wnt stimulation can lead to stem cell depletion and aging. [43] Klotho inhibition of Wnt signaling can inhibit cancer. [32] The anti-aging effects of klotho are also a consequence of increased resistance to inflammation and oxidative stress. [16]

Extracellular vesicles (EV) in young mice carried more copies of klotho-producing mRNA than those from old mice. Transfusing young EVs into older mice helped rebuild their muscles. [44]

The presence of senescent cells decreases α-klotho levels. Senolytic drugs reduce the level of these cells, allowing α-klotho levels to increase. [45]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000133116 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000058488 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Shiraki-Iida T, Nagai R, Kuro-o M, Nabeshima Y (January 1998). "Identification of the human klotho gene and its two transcripts encoding membrane and secreted klotho protein". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 242 (3): 626–630. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8019. PMID 9464267.

- ^ Dolegowska K, Marchelek-Mysliwiec M, Nowosiad-Magda M, Slawinski M, Dolegowska B (June 2019). "FGF19 subfamily members: FGF19 and FGF21". Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry. 75 (2): 229–240. doi: 10.1007/s13105-019-00675-7. PMC 6611749. PMID 30927227.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kuro-O M (January 2019). "The Klotho proteins in health and disease". Nature Reviews. Nephrology. 15 (1): 27–44. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0078-3. PMID 30455427. S2CID 53872296.

- ^ a b Lim K, Halim A, Lu TS, Ashworth A, Chong I (September 2019). "Klotho: A Major Shareholder in Vascular Aging Enterprises". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20 (18): E4637. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184637. PMC 6770519. PMID 31546756.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hanson K, Fisher K, Hooper NM (June 2021). "Exploiting the neuroprotective effects of α-klotho to tackle ageing- and neurodegeneration-related cognitive dysfunction". Neuronal Signaling. 5 (2): NS20200101. doi: 10.1042/NS20200101. PMC 8204227. PMID 34194816.

- ^ Kurt B, Kurtz A (March 2015). "Plasticity of renal endocrine function". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 308 (6): R455–R466. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00568.2013. PMID 25608752. S2CID 37452911.

- ^ Buendía P, Ramírez R, Aljama P, Carracedo J (2016). "Klotho Prevents Translocation of NFκB". Klotho. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 101. pp. 119–150. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2016.02.005. ISBN 9780128048191. PMID 27125740.

- ^ Martín-González C, González-Reimers E, Quintero-Platt G, Martínez-Riera A, Santolaria-Fernández F (May 2019). "Soluble α-Klotho in Liver Cirrhosis and Alcoholism". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 54 (3): 204–208. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agz019. PMC 6731336. PMID 30860544.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: klotho".

- ^ Schumann G, Liu C, O'Reilly P, Gao H, Song P, Xu B, et al. (December 2016). "KLB is associated with alcohol drinking, and its gene product β-Klotho is necessary for FGF21 regulation of alcohol preference". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (50): 14372–14377. Bibcode: 2016PNAS..11314372S. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611243113. PMC 5167198. PMID 27911795.

- ^ a b Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, Nandi A, Gurnani P, et al. (September 2005). "Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho". Science. 309 (5742): 1829–1833. Bibcode: 2005Sci...309.1829K. doi: 10.1126/science.1112766. PMC 2536606. PMID 16123266.

- ^ a b c d e Baranowska B, Kochanowski J (September 2020). "The metabolic, neuroprotective cardioprotective and antitumor effects of the Klotho protein". Neuro Endocrinology Letters. 41 (2): 69–75. PMID 33185993.

- ^ "Klotho Beta". Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, et al. (November 1997). "Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing". Nature. 390 (6655): 45–51. Bibcode: 1997Natur.390...45K. doi: 10.1038/36285. PMID 9363890. S2CID 4428141.

- ^ Arking DE, Krebsova A, Macek M, Macek M, Arking A, Mian IS, et al. (January 2002). "Association of human aging with a functional variant of klotho". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (2): 856–861. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99..856A. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022484299. PMC 117395. PMID 11792841.

- ^ Xiao NM, Zhang YM, Zheng Q, Gu J (May 2004). "Klotho is a serum factor related to human aging". Chinese Medical Journal. 117 (5): 742–747. PMID 15161545.[ permanent dead link]

- ^ Helsten T, Schwaederle M, Kurzrock R (September 2015). "Fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling in hereditary and neoplastic disease: biologic and clinical implications". Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 34 (3): 479–496. doi: 10.1007/s10555-015-9579-8. PMC 4573649. PMID 26224133.

- ^ Talukdar S, Owen BM, Song P, Hernandez G, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, et al. (February 2016). "FGF21 Regulates Sweet and Alcohol Preference". Cell Metabolism. 23 (2): 344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.008. PMC 4749404. PMID 26724861.

- ^ Flippo KH, Potthoff MJ (March 2021). "Metabolic Messengers: FGF21". Nature Metabolism. 3 (3): 309–317. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00354-2. PMC 8620721. PMID 33758421.

- ^ a b c Huang CL (May 2010). "Regulation of ion channels by secreted Klotho: mechanisms and implications". Kidney International. 77 (10): 855–860. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.73. PMID 20375979.

- ^ van Goor MK, Hoenderop JG, van der Wijst J (June 2017). "TRP channels in calcium homeostasis: from hormonal control to structure-function relationship of TRPV5 and TRPV6". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1864 (6): 883–893. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.11.027. PMID 27913205.

- ^ Wolf MT, An SW, Nie M, Bal MS, Huang CL (December 2014). "Klotho up-regulates renal calcium channel transient receptor potential vanilloid 5 (TRPV5) by intra- and extracellular N-glycosylation-dependent mechanisms". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 289 (52): 35849–35857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.616649. PMC 4276853. PMID 25378396.

- ^ Saghiv MS, Sira DB, Goldhammer E, Sagiv M (2017). "The effects of aerobic and anaerobic exercises on circulating soluble-Klotho and IGF-I in young and elderly adults and in CAD patients". Journal of Circulating Biomarkers. 6: 1849454417733388. doi: 10.1177/1849454417733388. PMC 5644364. PMID 29081845.

- ^ a b Olejnik A, Franczak A, Krzywonos-Zawadzka A, Kałużna-Oleksy M, Bil-Lula I (2018). "The Biological Role of Klotho Protein in the Development of Cardiovascular Diseases". BioMed Research International. 2018: 5171945. doi: 10.1155/2018/5171945. PMC 6323445. PMID 30671457.

- ^ Torbus-Paluszczak M, Bartman W, Adamczyk-Sowa M (October 2018). "Klotho protein in neurodegenerative disorders". Neurological Sciences. 39 (10): 1677–1682. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3496-x. PMC 6154120. PMID 30062646.

- ^ Vo HT, Laszczyk AM, King GD (August 2018). "Klotho, the Key to Healthy Brain Aging?". Brain Plasticity. 3 (2): 183–194. doi: 10.3233/BPL-170057. PMC 6091049. PMID 30151342.

- ^ a b Tozer L (4 July 2023). "Anti-ageing protein injection boosts monkeys' memories". Nature. 619 (7969): 234. Bibcode: 2023Natur.619..234T. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-02214-3. PMID 37402904. S2CID 259334272.

- ^ a b c d Zhou H, Pu S, Zhou H, Guo Y (2021). "Klotho as Potential Autophagy Regulator and Therapeutic Target". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 12: 755366. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.755366. PMC 8560683. PMID 34737707.

- ^ Adhikari BR, Uehara O, Matsuoka H, Takai R, Harada F, Utsunomiya M, et al. (September 2017). "Immunohistochemical evaluation of Klotho and DNA methyltransferase 3a in oral squamous cell carcinomas". Medical Molecular Morphology. 50 (3): 155–160. doi: 10.1007/s00795-017-0156-9. PMID 28303350. S2CID 22810635.

- ^ Paroni G, Panza F, De Cosmo S, Greco A, Seripa D, Mazzoccoli G (March 2019). "Klotho at the Edge of Alzheimer's Disease and Senile Depression". Molecular Neurobiology. 56 (3): 1908–1920. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1200-z. PMID 29978424. S2CID 49567009.

- ^ Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH (2020). "Alignment of Alzheimer's disease amyloid β-peptide and klotho". World Academy of Sciences Journal. 2 (6): 1. doi: 10.3892/wasj.2020.68. PMC 7521834. PMID 32999998.

- ^ Castner SA, Gupta S, Wang D, Moreno AJ, Park C, Chen C, et al. (July 2023). "Longevity factor klotho enhances cognition in aged nonhuman primates". Nature Aging. 3 (8): 931–937. doi: 10.1038/s43587-023-00441-x. PMC 10432271. PMID 37400721. S2CID 259322607.

- ^ a b c Veronesi F, Borsari V, Cherubini A, Fini M (October 2021). "Association of Klotho with physical performance and frailty in middle-aged and older adults: A systematic review". Experimental Gerontology. 154: 111518. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2021.111518. PMID 34407459. S2CID 237011996.

- ^ Dubal DB, Yokoyama JS, Zhu L, Broestl L, Worden K, Wang D, et al. (May 2014). "Life extension factor klotho enhances cognition". Cell Reports. 7 (4): 1065–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.076. PMC 4176932. PMID 24813892.

- ^ Kuro-o M (October 2009). "Klotho and aging". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1790 (10): 1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.02.005. PMC 2743784. PMID 19230844.

- ^ Medici D, Razzaque MS, Deluca S, Rector TL, Hou B, Kang K, et al. (August 2008). "FGF-23-Klotho signaling stimulates proliferation and prevents vitamin D-induced apoptosis". The Journal of Cell Biology. 182 (3): 459–465. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803024. PMC 2500132. PMID 18678710.

- ^ Tsujikawa H, Kurotaki Y, Fujimori T, Fukuda K, Nabeshima Y (December 2003). "Klotho, a gene related to a syndrome resembling human premature aging, functions in a negative regulatory circuit of vitamin D endocrine system". Molecular Endocrinology. 17 (12): 2393–2403. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0048. hdl: 2433/145275. PMID 14528024.

- ^ Imura A, Tsuji Y, Murata M, Maeda R, Kubota K, Iwano A, et al. (June 2007). "alpha-Klotho as a regulator of calcium homeostasis". Science. 316 (5831): 1615–1618. Bibcode: 2007Sci...316.1615I. doi: 10.1126/science.1135901. PMID 17569864. S2CID 40529168.

- ^ Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, Liu J, Cao L, Chen J, et al. (August 2007). "Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging". Science. 317 (5839): 803–806. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.73. PMID 17690294.

- ^ Irving M (2021-12-10). ""Young blood" particles that help old mice fight aging identified". New Atlas. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ^ Irving M (2022-03-16). "Senolytic drugs boost protein that protects against effects of aging". New Atlas. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

Further reading

- Shimoyama Y, Taki K, Mitsuda Y, Tsuruta Y, Hamajima N, Niwa T (2009). "KLOTHO gene polymorphisms G-395A and C1818T are associated with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and uric acid in Japanese hemodialysis patients". American Journal of Nephrology. 30 (4): 383–388. doi: 10.1159/000235686. PMID 19690404. S2CID 38277163.

- Choi BH, Kim CG, Lim Y, Lee YH, Shin SY (January 2010). "Transcriptional activation of the human Klotho gene by epidermal growth factor in HEK293 cells; role of Egr-1". Gene. 450 (1–2): 121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.11.004. PMID 19913601.

- Fukumoto S (April 2009). "[Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and bone. Regulation of calcium and phosphate metabolism by FGF23/Klotho]". Clinical Calcium. 19 (4): 523–528. PMID 19329831.

- Nabeshima Y (December 2000). "Challenge of overcoming aging-related disorders". Journal of Dermatological Science. 24 (Suppl 1): S15–S21. doi: 10.1016/S0923-1811(00)00136-5. PMID 11137391.

- Razzaque MS (March 2009). "FGF23-mediated regulation of systemic phosphate homeostasis: is Klotho an essential player?". American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 296 (3): F470–F476. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90538.2008. PMC 2660189. PMID 19019915.

- Menon R, Pearce B, Velez DR, Merialdi M, Williams SM, Fortunato SJ, Thorsen P (June 2009). "Racial disparity in pathophysiologic pathways of preterm birth based on genetic variants". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 7: 62. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-62. PMC 2714850. PMID 19527514.

- Prié D, Ureña Torres P, Friedlander G (May 2009). "[Fibroblast Growth Factor 23-Klotho: a new axis of phosphate balance control]". Médecine/Sciences. 25 (5): 489–495. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2009255489. PMID 19480830.

- Torres PU, Prié D, Beck L, De Brauwere D, Leroy C, Friedlander G (January 2009). "Klotho gene, phosphocalcic metabolism, and survival in dialysis". Journal of Renal Nutrition. 19 (1): 50–56. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2008.10.018. PMID 19121771.

- Halaschek-Wiener J, Amirabbasi-Beik M, Monfared N, Pieczyk M, Sailer C, Kollar A, et al. (August 2009). Bridger JM (ed.). "Genetic variation in healthy oldest-old". PLOS ONE. 4 (8): e6641. Bibcode: 2009PLoSO...4.6641H. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006641. PMC 2722017. PMID 19680556.

- Shimoyama Y, Nishio K, Hamajima N, Niwa T (August 2009). "KLOTHO gene polymorphisms G-395A and C1818T are associated with lipid and glucose metabolism, bone mineral density and systolic blood pressure in Japanese healthy subjects". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 406 (1–2): 134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.06.011. PMID 19539617.

- Wang HL, Xu Q, Wang Z, Zhang YH, Si LY, Li XJ, et al. (March 2010). "A potential regulatory single nucleotide polymorphism in the promoter of the Klotho gene may be associated with essential hypertension in the Chinese Han population". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 411 (5–6): 386–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.12.004. PMID 20005218.

- Yerges LM, Klei L, Cauley JA, Roeder K, Kammerer CM, Moffett SP, et al. (December 2009). "High-density association study of 383 candidate genes for volumetric BMD at the femoral neck and lumbar spine among older men". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 24 (12): 2039–2049. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090524. PMC 2791518. PMID 19453261.

- Torres PU, Prié D, Molina-Blétry V, Beck L, Silve C, Friedlander G (April 2007). "Klotho: an antiaging protein involved in mineral and vitamin D metabolism". Kidney International. 71 (8): 730–737. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002163. PMID 17332731.

- Kurosu H, Kuro-o M (July 2008). "The Klotho gene family and the endocrine fibroblast growth factors". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 17 (4): 368–372. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282ffd994. PMID 18660672. S2CID 23104131.

- Kuro-o M (October 2009). "Klotho and aging". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1790 (10): 1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.02.005. PMC 2743784. PMID 19230844.

- Wolf I, Laitman Y, Rubinek T, Abramovitz L, Novikov I, Beeri R, et al. (January 2010). "Functional variant of KLOTHO: a breast cancer risk modifier among BRCA1 mutation carriers of Ashkenazi origin". Oncogene. 29 (1): 26–33. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.301. PMID 19802015.

- Invidia L, Salvioli S, Altilia S, Pierini M, Panourgia MP, Monti D, et al. (February 2010). "The frequency of Klotho KL-VS polymorphism in a large Italian population, from young subjects to centenarians, suggests the presence of specific time windows for its effect". Biogerontology. 11 (1): 67–73. doi: 10.1007/s10522-009-9229-z. PMID 19421891. S2CID 25150050.

- Nabeshima Y (July 2008). "[Discovery of alpha-Klotho and FGF23 unveiled new insight into calcium and phosphate homeostasis]". Clinical Calcium. 18 (7): 923–934. PMID 18591743.

- Chen SN, Cilingiroglu M, Todd J, Lombardi R, Willerson JT, Gotto AM, et al. (October 2009). "Candidate genetic analysis of plasma high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and severity of coronary atherosclerosis". BMC Medical Genetics. 10: 111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-111. PMC 2775733. PMID 19878569.

- Zhang R, Zheng F (September 2008). "PPAR-gamma and aging: one link through klotho?". Kidney International. 74 (6): 702–704. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.382. PMID 18756295.

- Kim JH, Hwang KH, Park KS, Kong ID, Cha SK (March 2015). "Biological Role of Anti-aging Protein Klotho". Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 5 (1): 1–6. doi: 10.15280/jlm.2015.5.1.1. PMC 4608225. PMID 26528423.

External links

- "KL klotho [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene". NCBI. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- "GenAge entry for KL (Homo sapiens)". Human Ageing Genomic Resources.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.

| KL | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | KL, entrez:9365, klotho, HFTC3, KLA | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 604824 MGI: 1101771 HomoloGene: 68415 GeneCards: KL | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Klotho is an enzyme that in humans is encoded by the KL gene. [5] The three subfamilies of klotho are α-klotho, β-klotho, and γ-klotho. [6] α-klotho activates FGF23, and β-klotho activates FGF19 and FGF21. [7] When the subfamily is not specified, the word "klotho" typically refers to the α-klotho subfamily, because α-klotho was discovered before the other members. [8] [7]

α-klotho is highly expressed in the brain, liver and kidney. [9] β-klotho is predominantly expressed in the liver. [10] [9] γ-klotho is expressed in the skin. [9]

Klotho can exist in a membrane-bound form or a (hormonal) soluble, circulating form. [11] Proteases can convert the membrane-bound form into the circulating form. [12]

The KL gene encodes a type-I single-pass transmembrane protein [7] that is related to β-glucuronidases. Reduced production of this protein has been observed in patients with chronic kidney failure (CKF), and this may be one of the factors underlying degenerative processes (e.g., arteriosclerosis, osteoporosis, and skin atrophy) seen in CKF. Mutations within the family have been associated with ageing, bone loss and alcohol consumption. [13] [14] Transgenic mice that overexpress Klotho live longer than wild-type mice. [15]

Structure

The α-klotho gene is located on chromosome 13, and is translated into a single-pass integral membrane protein. [9] The intracellular portion of the α-klotho protein is short (11 amino acids), whereas the extracellular portion is long (980 amino acids). [9] The transmembrane portion is also comparatively short (21 amino acids). [9] The extracellular portion contains two repeat sequences, termed the KL1 (about 450 amino acids) and KL2 (about 430 amino acids) domains. [9] [7] In the kidney and the choroid plexus of the brain, the transmembrane protein can be proteolytically cleaved to produce a 130- Kilo- Dalton, soluble form of α-klotho protein, released into the circulation and cerebrospinal fluid, respectively. [9] In humans, the secreted form of klotho is more dominant than the membrane form. [16]

The β-Klotho gene is located on chromosome 4. The protein shares homology (43.1% identity and 60.1% similarity) with α-klotho. [17] It should not be confused with the alpha-cut and beta-cut of alpha-klotho, which releases KL1+KL2 and KL2 domain, respectively.

Function

Klotho is a transmembrane protein that, in addition to other effects, provides some control over the sensitivity of the organism to insulin and appears to be involved in ageing. Its discovery was documented in 1997 by Makoto Kuro-o et al. [18] The name of the gene comes from Klotho or Clotho, one of the Moirai, or Fates, in Greek mythology, who spins the thread of human life. [7]

The klotho protein is a novel β-glucuronidase ( EC number 3.2.1.31) capable of hydrolyzing steroid β-glucuronides. Genetic variants in KLOTHO have been associated with human aging, [19] and klotho protein has been shown to be a circulating factor detectable in serum that declines with age. [20]

The binding of the endocrine fibroblast growth factors (FGF's, viz., FGF19 and FGF21) to their fibroblast growth factor receptors, is promoted via their interactions as co-receptors with β-klotho. [21] [22] [16] [7] Loss of β-Klotho abolishes all effects of FGF21. [23]

α-klotho, which binds to the endocrine FGF FGF23 changes cellular calcium homeostasis, by both increasing the expression and activity of TRPV5 (decreasing phosphate reabsorption in the kidney) and decreasing that of TRPC6 (decreasing phosphate absorption from the intestine). [24] α-klotho increases kidney calcium reabsorption by stabilizing TPRV5. [25] About 95% to 98% of Ca2+ filtered from the blood by the kidney is normally reabsorbed by the kidney's renal tubule, which is mediated by TRPV5. [26]

Clinical significance

α-klotho can suppress oxidative stress and inflammation, thereby reducing endothelial dysfunction and atherosclerosis. [8] Blood plasma α-klotho is increased by aerobic exercise, thereby reducing endothelial dysfunction. [27]

β-klotho activation of FGF21 protein has a protective effect on heart muscle cells. [28] Obesity is characterized by FGF21 resistance, believed to be caused by the inhibition of β-klotho by the inflammatory cell signalling protein ( cytokine) tumor necrosis factor alpha, [28] but there is evidence against this mechanism. [16]

Klotho is required for oligodendrocyte maturation, myelin integrity, and can protect neurons from toxic effects. [29] Mice deficient in klotho have a reduced number of synapses and cognitive deficits, whereas mice overexpressing klotho have enhanced learning and memory. [30] Research with injections of klotho in primates demonstrates a positive effect on memory that lasts for as long as two weeks. [31]

Reduced klotho expression is seen in the lung macrophages of smokers. [32] An abnormal form of autophagy associated with reduced expression of klotho is linked to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. [32] (Although normal autophagy helps maintain muscle, excessive autophagy causes loss of muscle mass. [32])

It has been found that the decreased klotho expression may be due to DNA hypermethylation, which may have been induced by the overexpression of DNMT3a. [33] Klotho may be a reliable gene for early detection of methylation changes in oral tissues, and can be used as a target for therapeutic modification in oral cancer during the early stages.

Klotho-deficient mice manifest a syndrome resembling accelerated human ageing and display extensive and accelerated arteriosclerosis. Additionally, they exhibit impaired endothelium dependent vasodilation and impaired angiogenesis, suggesting that klotho protein may protect the cardiovascular system through endothelium-derived nitric oxide production. [16]

Klotho could play a protective role in Alzheimer's disease patients. [34] [35]

Research with injections of α-klotho in primates suggests a positive effect on memory that could have implications for research with humans. [31] Interestingly the cognitive effects in rhesus monkeys were observed even with subcutaneous injection despite previous results showing that klotho protein fails to cross the blood–brain barrier. [36]

Effects on aging

Reduced α-klotho or FGF23 can result in impaired phosphate excretion from the kidney, leading to hyperphosphatemia. [7] In mice, this leads to a phenotype characteristic of premature aging, which can be mitigated by feeding the mice a low phosphate diet. [7]

The plasma (soluble) form of α-klotho is most easily measured, and has been shown to decrease after 40 years of age in humans. [37] Lower plasma levels of α-klotho in older adults is associated with increased frailty and all-cause mortality. [37] Physical activity has been shown to increase plasma α-klotho. [37]

Mice lacking either fibroblast growth factor 23 or the α-klotho enzyme display premature aging due to hyperphosphatemia. [24] Many of these symptoms can be alleviated by feeding the mice a low phosphate diet. [7]

Although the majority of research has explored klotho's absence, it was demonstrated that klotho over-expression in mice extended their average life span between 19% and 31% compared to normal mice. [15] In addition, variations in the Klotho gene (SNP Rs9536314) are associated with both life extension and increased cognition in human populations and mice, but only if the gene expression was heterozygous, not homozygous. [38] [9] The cognitive benefits of α-klotho are primarily seen late in life. [9]

Klotho increases membrane expression of the inward rectifier ATP-dependent potassium channel ROMK. [24] Klotho-deficient mice show increased production of vitamin D, and altered mineral-ion homeostasis is suggested to cause premature aging‑like phenotypes, because reduced vitamin D activity from dietary restriction reverses the premature aging‑like phenotypes and prolongs survival in these mutants. These results suggest that aging‑like phenotypes were due to klotho-associated vitamin D metabolic abnormalities (hypervitaminosis). [39] [40] [41] [42]

Klotho is an antagonist of the Wnt signaling pathway, and chronic Wnt stimulation can lead to stem cell depletion and aging. [43] Klotho inhibition of Wnt signaling can inhibit cancer. [32] The anti-aging effects of klotho are also a consequence of increased resistance to inflammation and oxidative stress. [16]

Extracellular vesicles (EV) in young mice carried more copies of klotho-producing mRNA than those from old mice. Transfusing young EVs into older mice helped rebuild their muscles. [44]

The presence of senescent cells decreases α-klotho levels. Senolytic drugs reduce the level of these cells, allowing α-klotho levels to increase. [45]

References

- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000133116 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000058488 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Shiraki-Iida T, Nagai R, Kuro-o M, Nabeshima Y (January 1998). "Identification of the human klotho gene and its two transcripts encoding membrane and secreted klotho protein". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 242 (3): 626–630. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.8019. PMID 9464267.

- ^ Dolegowska K, Marchelek-Mysliwiec M, Nowosiad-Magda M, Slawinski M, Dolegowska B (June 2019). "FGF19 subfamily members: FGF19 and FGF21". Journal of Physiology and Biochemistry. 75 (2): 229–240. doi: 10.1007/s13105-019-00675-7. PMC 6611749. PMID 30927227.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Kuro-O M (January 2019). "The Klotho proteins in health and disease". Nature Reviews. Nephrology. 15 (1): 27–44. doi: 10.1038/s41581-018-0078-3. PMID 30455427. S2CID 53872296.

- ^ a b Lim K, Halim A, Lu TS, Ashworth A, Chong I (September 2019). "Klotho: A Major Shareholder in Vascular Aging Enterprises". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 20 (18): E4637. doi: 10.3390/ijms20184637. PMC 6770519. PMID 31546756.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hanson K, Fisher K, Hooper NM (June 2021). "Exploiting the neuroprotective effects of α-klotho to tackle ageing- and neurodegeneration-related cognitive dysfunction". Neuronal Signaling. 5 (2): NS20200101. doi: 10.1042/NS20200101. PMC 8204227. PMID 34194816.

- ^ Kurt B, Kurtz A (March 2015). "Plasticity of renal endocrine function". American Journal of Physiology. Regulatory, Integrative and Comparative Physiology. 308 (6): R455–R466. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00568.2013. PMID 25608752. S2CID 37452911.

- ^ Buendía P, Ramírez R, Aljama P, Carracedo J (2016). "Klotho Prevents Translocation of NFκB". Klotho. Vitamins & Hormones. Vol. 101. pp. 119–150. doi: 10.1016/bs.vh.2016.02.005. ISBN 9780128048191. PMID 27125740.

- ^ Martín-González C, González-Reimers E, Quintero-Platt G, Martínez-Riera A, Santolaria-Fernández F (May 2019). "Soluble α-Klotho in Liver Cirrhosis and Alcoholism". Alcohol and Alcoholism. 54 (3): 204–208. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agz019. PMC 6731336. PMID 30860544.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: klotho".

- ^ Schumann G, Liu C, O'Reilly P, Gao H, Song P, Xu B, et al. (December 2016). "KLB is associated with alcohol drinking, and its gene product β-Klotho is necessary for FGF21 regulation of alcohol preference". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 113 (50): 14372–14377. Bibcode: 2016PNAS..11314372S. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1611243113. PMC 5167198. PMID 27911795.

- ^ a b Kurosu H, Yamamoto M, Clark JD, Pastor JV, Nandi A, Gurnani P, et al. (September 2005). "Suppression of aging in mice by the hormone Klotho". Science. 309 (5742): 1829–1833. Bibcode: 2005Sci...309.1829K. doi: 10.1126/science.1112766. PMC 2536606. PMID 16123266.

- ^ a b c d e Baranowska B, Kochanowski J (September 2020). "The metabolic, neuroprotective cardioprotective and antitumor effects of the Klotho protein". Neuro Endocrinology Letters. 41 (2): 69–75. PMID 33185993.

- ^ "Klotho Beta". Retrieved 12 September 2023.

- ^ Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, et al. (November 1997). "Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing". Nature. 390 (6655): 45–51. Bibcode: 1997Natur.390...45K. doi: 10.1038/36285. PMID 9363890. S2CID 4428141.

- ^ Arking DE, Krebsova A, Macek M, Macek M, Arking A, Mian IS, et al. (January 2002). "Association of human aging with a functional variant of klotho". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 99 (2): 856–861. Bibcode: 2002PNAS...99..856A. doi: 10.1073/pnas.022484299. PMC 117395. PMID 11792841.

- ^ Xiao NM, Zhang YM, Zheng Q, Gu J (May 2004). "Klotho is a serum factor related to human aging". Chinese Medical Journal. 117 (5): 742–747. PMID 15161545.[ permanent dead link]

- ^ Helsten T, Schwaederle M, Kurzrock R (September 2015). "Fibroblast growth factor receptor signaling in hereditary and neoplastic disease: biologic and clinical implications". Cancer and Metastasis Reviews. 34 (3): 479–496. doi: 10.1007/s10555-015-9579-8. PMC 4573649. PMID 26224133.

- ^ Talukdar S, Owen BM, Song P, Hernandez G, Zhang Y, Zhou Y, et al. (February 2016). "FGF21 Regulates Sweet and Alcohol Preference". Cell Metabolism. 23 (2): 344–349. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2015.12.008. PMC 4749404. PMID 26724861.

- ^ Flippo KH, Potthoff MJ (March 2021). "Metabolic Messengers: FGF21". Nature Metabolism. 3 (3): 309–317. doi: 10.1038/s42255-021-00354-2. PMC 8620721. PMID 33758421.

- ^ a b c Huang CL (May 2010). "Regulation of ion channels by secreted Klotho: mechanisms and implications". Kidney International. 77 (10): 855–860. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.73. PMID 20375979.

- ^ van Goor MK, Hoenderop JG, van der Wijst J (June 2017). "TRP channels in calcium homeostasis: from hormonal control to structure-function relationship of TRPV5 and TRPV6". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Cell Research. 1864 (6): 883–893. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2016.11.027. PMID 27913205.

- ^ Wolf MT, An SW, Nie M, Bal MS, Huang CL (December 2014). "Klotho up-regulates renal calcium channel transient receptor potential vanilloid 5 (TRPV5) by intra- and extracellular N-glycosylation-dependent mechanisms". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 289 (52): 35849–35857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.616649. PMC 4276853. PMID 25378396.

- ^ Saghiv MS, Sira DB, Goldhammer E, Sagiv M (2017). "The effects of aerobic and anaerobic exercises on circulating soluble-Klotho and IGF-I in young and elderly adults and in CAD patients". Journal of Circulating Biomarkers. 6: 1849454417733388. doi: 10.1177/1849454417733388. PMC 5644364. PMID 29081845.

- ^ a b Olejnik A, Franczak A, Krzywonos-Zawadzka A, Kałużna-Oleksy M, Bil-Lula I (2018). "The Biological Role of Klotho Protein in the Development of Cardiovascular Diseases". BioMed Research International. 2018: 5171945. doi: 10.1155/2018/5171945. PMC 6323445. PMID 30671457.

- ^ Torbus-Paluszczak M, Bartman W, Adamczyk-Sowa M (October 2018). "Klotho protein in neurodegenerative disorders". Neurological Sciences. 39 (10): 1677–1682. doi: 10.1007/s10072-018-3496-x. PMC 6154120. PMID 30062646.

- ^ Vo HT, Laszczyk AM, King GD (August 2018). "Klotho, the Key to Healthy Brain Aging?". Brain Plasticity. 3 (2): 183–194. doi: 10.3233/BPL-170057. PMC 6091049. PMID 30151342.

- ^ a b Tozer L (4 July 2023). "Anti-ageing protein injection boosts monkeys' memories". Nature. 619 (7969): 234. Bibcode: 2023Natur.619..234T. doi: 10.1038/d41586-023-02214-3. PMID 37402904. S2CID 259334272.

- ^ a b c d Zhou H, Pu S, Zhou H, Guo Y (2021). "Klotho as Potential Autophagy Regulator and Therapeutic Target". Frontiers in Pharmacology. 12: 755366. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.755366. PMC 8560683. PMID 34737707.

- ^ Adhikari BR, Uehara O, Matsuoka H, Takai R, Harada F, Utsunomiya M, et al. (September 2017). "Immunohistochemical evaluation of Klotho and DNA methyltransferase 3a in oral squamous cell carcinomas". Medical Molecular Morphology. 50 (3): 155–160. doi: 10.1007/s00795-017-0156-9. PMID 28303350. S2CID 22810635.

- ^ Paroni G, Panza F, De Cosmo S, Greco A, Seripa D, Mazzoccoli G (March 2019). "Klotho at the Edge of Alzheimer's Disease and Senile Depression". Molecular Neurobiology. 56 (3): 1908–1920. doi: 10.1007/s12035-018-1200-z. PMID 29978424. S2CID 49567009.

- ^ Lehrer S, Rheinstein PH (2020). "Alignment of Alzheimer's disease amyloid β-peptide and klotho". World Academy of Sciences Journal. 2 (6): 1. doi: 10.3892/wasj.2020.68. PMC 7521834. PMID 32999998.

- ^ Castner SA, Gupta S, Wang D, Moreno AJ, Park C, Chen C, et al. (July 2023). "Longevity factor klotho enhances cognition in aged nonhuman primates". Nature Aging. 3 (8): 931–937. doi: 10.1038/s43587-023-00441-x. PMC 10432271. PMID 37400721. S2CID 259322607.

- ^ a b c Veronesi F, Borsari V, Cherubini A, Fini M (October 2021). "Association of Klotho with physical performance and frailty in middle-aged and older adults: A systematic review". Experimental Gerontology. 154: 111518. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2021.111518. PMID 34407459. S2CID 237011996.

- ^ Dubal DB, Yokoyama JS, Zhu L, Broestl L, Worden K, Wang D, et al. (May 2014). "Life extension factor klotho enhances cognition". Cell Reports. 7 (4): 1065–1076. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.03.076. PMC 4176932. PMID 24813892.

- ^ Kuro-o M (October 2009). "Klotho and aging". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1790 (10): 1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.02.005. PMC 2743784. PMID 19230844.

- ^ Medici D, Razzaque MS, Deluca S, Rector TL, Hou B, Kang K, et al. (August 2008). "FGF-23-Klotho signaling stimulates proliferation and prevents vitamin D-induced apoptosis". The Journal of Cell Biology. 182 (3): 459–465. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803024. PMC 2500132. PMID 18678710.

- ^ Tsujikawa H, Kurotaki Y, Fujimori T, Fukuda K, Nabeshima Y (December 2003). "Klotho, a gene related to a syndrome resembling human premature aging, functions in a negative regulatory circuit of vitamin D endocrine system". Molecular Endocrinology. 17 (12): 2393–2403. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0048. hdl: 2433/145275. PMID 14528024.

- ^ Imura A, Tsuji Y, Murata M, Maeda R, Kubota K, Iwano A, et al. (June 2007). "alpha-Klotho as a regulator of calcium homeostasis". Science. 316 (5831): 1615–1618. Bibcode: 2007Sci...316.1615I. doi: 10.1126/science.1135901. PMID 17569864. S2CID 40529168.

- ^ Liu H, Fergusson MM, Castilho RM, Liu J, Cao L, Chen J, et al. (August 2007). "Augmented Wnt signaling in a mammalian model of accelerated aging". Science. 317 (5839): 803–806. doi: 10.1038/ki.2010.73. PMID 17690294.

- ^ Irving M (2021-12-10). ""Young blood" particles that help old mice fight aging identified". New Atlas. Retrieved 2021-12-11.

- ^ Irving M (2022-03-16). "Senolytic drugs boost protein that protects against effects of aging". New Atlas. Retrieved 2022-03-16.

Further reading

- Shimoyama Y, Taki K, Mitsuda Y, Tsuruta Y, Hamajima N, Niwa T (2009). "KLOTHO gene polymorphisms G-395A and C1818T are associated with low-density lipoprotein cholesterol and uric acid in Japanese hemodialysis patients". American Journal of Nephrology. 30 (4): 383–388. doi: 10.1159/000235686. PMID 19690404. S2CID 38277163.

- Choi BH, Kim CG, Lim Y, Lee YH, Shin SY (January 2010). "Transcriptional activation of the human Klotho gene by epidermal growth factor in HEK293 cells; role of Egr-1". Gene. 450 (1–2): 121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2009.11.004. PMID 19913601.

- Fukumoto S (April 2009). "[Chronic kidney disease (CKD) and bone. Regulation of calcium and phosphate metabolism by FGF23/Klotho]". Clinical Calcium. 19 (4): 523–528. PMID 19329831.

- Nabeshima Y (December 2000). "Challenge of overcoming aging-related disorders". Journal of Dermatological Science. 24 (Suppl 1): S15–S21. doi: 10.1016/S0923-1811(00)00136-5. PMID 11137391.

- Razzaque MS (March 2009). "FGF23-mediated regulation of systemic phosphate homeostasis: is Klotho an essential player?". American Journal of Physiology. Renal Physiology. 296 (3): F470–F476. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90538.2008. PMC 2660189. PMID 19019915.

- Menon R, Pearce B, Velez DR, Merialdi M, Williams SM, Fortunato SJ, Thorsen P (June 2009). "Racial disparity in pathophysiologic pathways of preterm birth based on genetic variants". Reproductive Biology and Endocrinology. 7: 62. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-62. PMC 2714850. PMID 19527514.

- Prié D, Ureña Torres P, Friedlander G (May 2009). "[Fibroblast Growth Factor 23-Klotho: a new axis of phosphate balance control]". Médecine/Sciences. 25 (5): 489–495. doi: 10.1051/medsci/2009255489. PMID 19480830.

- Torres PU, Prié D, Beck L, De Brauwere D, Leroy C, Friedlander G (January 2009). "Klotho gene, phosphocalcic metabolism, and survival in dialysis". Journal of Renal Nutrition. 19 (1): 50–56. doi: 10.1053/j.jrn.2008.10.018. PMID 19121771.

- Halaschek-Wiener J, Amirabbasi-Beik M, Monfared N, Pieczyk M, Sailer C, Kollar A, et al. (August 2009). Bridger JM (ed.). "Genetic variation in healthy oldest-old". PLOS ONE. 4 (8): e6641. Bibcode: 2009PLoSO...4.6641H. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006641. PMC 2722017. PMID 19680556.

- Shimoyama Y, Nishio K, Hamajima N, Niwa T (August 2009). "KLOTHO gene polymorphisms G-395A and C1818T are associated with lipid and glucose metabolism, bone mineral density and systolic blood pressure in Japanese healthy subjects". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 406 (1–2): 134–138. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.06.011. PMID 19539617.

- Wang HL, Xu Q, Wang Z, Zhang YH, Si LY, Li XJ, et al. (March 2010). "A potential regulatory single nucleotide polymorphism in the promoter of the Klotho gene may be associated with essential hypertension in the Chinese Han population". Clinica Chimica Acta; International Journal of Clinical Chemistry. 411 (5–6): 386–390. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.12.004. PMID 20005218.

- Yerges LM, Klei L, Cauley JA, Roeder K, Kammerer CM, Moffett SP, et al. (December 2009). "High-density association study of 383 candidate genes for volumetric BMD at the femoral neck and lumbar spine among older men". Journal of Bone and Mineral Research. 24 (12): 2039–2049. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.090524. PMC 2791518. PMID 19453261.

- Torres PU, Prié D, Molina-Blétry V, Beck L, Silve C, Friedlander G (April 2007). "Klotho: an antiaging protein involved in mineral and vitamin D metabolism". Kidney International. 71 (8): 730–737. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002163. PMID 17332731.

- Kurosu H, Kuro-o M (July 2008). "The Klotho gene family and the endocrine fibroblast growth factors". Current Opinion in Nephrology and Hypertension. 17 (4): 368–372. doi: 10.1097/MNH.0b013e3282ffd994. PMID 18660672. S2CID 23104131.

- Kuro-o M (October 2009). "Klotho and aging". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects. 1790 (10): 1049–1058. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagen.2009.02.005. PMC 2743784. PMID 19230844.

- Wolf I, Laitman Y, Rubinek T, Abramovitz L, Novikov I, Beeri R, et al. (January 2010). "Functional variant of KLOTHO: a breast cancer risk modifier among BRCA1 mutation carriers of Ashkenazi origin". Oncogene. 29 (1): 26–33. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.301. PMID 19802015.

- Invidia L, Salvioli S, Altilia S, Pierini M, Panourgia MP, Monti D, et al. (February 2010). "The frequency of Klotho KL-VS polymorphism in a large Italian population, from young subjects to centenarians, suggests the presence of specific time windows for its effect". Biogerontology. 11 (1): 67–73. doi: 10.1007/s10522-009-9229-z. PMID 19421891. S2CID 25150050.

- Nabeshima Y (July 2008). "[Discovery of alpha-Klotho and FGF23 unveiled new insight into calcium and phosphate homeostasis]". Clinical Calcium. 18 (7): 923–934. PMID 18591743.

- Chen SN, Cilingiroglu M, Todd J, Lombardi R, Willerson JT, Gotto AM, et al. (October 2009). "Candidate genetic analysis of plasma high-density lipoprotein-cholesterol and severity of coronary atherosclerosis". BMC Medical Genetics. 10: 111. doi: 10.1186/1471-2350-10-111. PMC 2775733. PMID 19878569.

- Zhang R, Zheng F (September 2008). "PPAR-gamma and aging: one link through klotho?". Kidney International. 74 (6): 702–704. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.382. PMID 18756295.

- Kim JH, Hwang KH, Park KS, Kong ID, Cha SK (March 2015). "Biological Role of Anti-aging Protein Klotho". Journal of Lifestyle Medicine. 5 (1): 1–6. doi: 10.15280/jlm.2015.5.1.1. PMC 4608225. PMID 26528423.

External links

- "KL klotho [Homo sapiens (human)] - Gene". NCBI. U.S. National Library of Medicine. Retrieved 2023-03-20.

- "GenAge entry for KL (Homo sapiens)". Human Ageing Genomic Resources.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.