Fishieman15 (

talk |

contribs) |

165.86.81.20 (

talk) |

||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

Side effects in Queensland: There is a vocal minority<ref>Surveys conducted over recent years by the Queensland Office of Economic and Statistical Research, the Local Government Association of Queensland, Central Queensland University and the Queensland Oral Health Alliance have consistently demonstrated that between 60% and 70% of Queenslanders support fluoridation.</ref> in Queensland that claims negative effects from the addition of fluoride to drinking water. To date there has been no evidence linking the addition of fluoride to the negative effects claimed by those opposed to fluoride within Queensland. |

Side effects in Queensland: There is a vocal minority<ref>Surveys conducted over recent years by the Queensland Office of Economic and Statistical Research, the Local Government Association of Queensland, Central Queensland University and the Queensland Oral Health Alliance have consistently demonstrated that between 60% and 70% of Queenslanders support fluoridation.</ref> in Queensland that claims negative effects from the addition of fluoride to drinking water. To date there has been no evidence linking the addition of fluoride to the negative effects claimed by those opposed to fluoride within Queensland. |

||

Claims about the negative effects of the addition of fluoride within Queensland are unsupported, as the addition of fluoride to drinking water supplies has only occurred in major metropolitan areas since late 2008, and no studies have been conducted to discern what effects have resulted specifically in Queensland as a consequence. For example, the claim that in 2008-2009 the Queensland Police recorded +40% increase in juvenile violence related crimes and all worst types of crimes increased more than the national average {{Citation needed}} might be linked to the addition of fluoride does not have merit |

Claims about the negative effects of the addition of fluoride within Queensland are unsupported, as the addition of fluoride to drinking water supplies has only occurred in major metropolitan areas since late 2008, and no studies have been conducted to discern what effects have resulted specifically in Queensland as a consequence. For example, the claim that in 2008-2009 the Queensland Police recorded +40% increase in juvenile violence related crimes and all worst types of crimes increased more than the national average {{Citation needed}} might be linked to the addition of fluoride does not have merit. Such consequences could not have been possible given that fluoride was not in the water in Queensland long enough or in the amount necessary to cause any negative effect that might have contributed to the increase in violent crime. Such a claim links an event that shares the same time period and falsely associates a cause and effect between the two, also known as a [[Post hoc ergo propter hoc]] fallacy. Additionally, some anti-fluoridation scientists have claimed a negative effect cause by augmented accumulation of lead in the brain. According to Prof. [[Roger Masters]]' studies, lead accumulation is induced by the Silicofluorides used to fluoridate water which do not electrolise in F- and Si+ ions as simplistically described by fluoridation's supporters and government agencies. Again, such claims do not relate to Queensland as this research was conducted in 2001 based on surveys of populations in the United States <ref>[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11233755 Association of silicofluoride treated water with elevated blood lead. Masters, Coplan, Hone, Dykes. 2000]</ref> There have been no similar studies within Queensland. Between 2007 and 2010, Queensland Health recorded + 40% increase in diabetes {{Citation needed}} and in 2007 Queensland's dental health was at least better than Tasmania's in 2008 {{Citation needed}}; after fluoridation, Queensland's dental health considerably worsened despite the national consumes of sugar diminished 20% {{Citation needed}}. The substantial increase in diabetes cases has been associated by some independent researchers to the semi-unknown bio-dynamics of fluorinated ammino-acids that are stongly bipolar and super-hydrophobic{{Citation needed}}. The worsened dental health was eventually a simple effect of the increased number of people who did not regularly brush their teeth because wrongly thinking that fluoride ingestion could successfully replace oral hygiene after meals{{Citation needed}}. |

||

An exception exists in [[Western Australia]] where approximately 20,000 residents within the [[Busselton]], [[Vasse]] and [[Wonnerup]] townsites, do not receive artificially fluoridated water.<ref>[http://www.busseltonwater.wa.gov.au/OurWater.aspx Busselton Water (Understanding our Natural Groundwater Resource)]</ref> |

An exception exists in [[Western Australia]] where approximately 20,000 residents within the [[Busselton]], [[Vasse]] and [[Wonnerup]] townsites, do not receive artificially fluoridated water.<ref>[http://www.busseltonwater.wa.gov.au/OurWater.aspx Busselton Water (Understanding our Natural Groundwater Resource)]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 00:25, 22 December 2011

Human or Artificial Fluoridation of water, salt, and milk varies from country to country. Water fluoridation has been introduced to varying degrees in many countries, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Ireland, Malaysia, the U.S., and Vietnam, [1] and is used by 5.7% of people worldwide. [2] Continental Europe largely does not fluoridate water, although some of its countries fluoridate salt; locations have discontinued water fluoridation in Germany, the Netherlands, and other countries. [2] Although health and dental organizations support water fluoridation in the countries that practice water fluoridation, [3] there has been considerable opposition to water fluoridation whenever it is proposed.

Africa

Egypt

Egypt does not fluoridate water, although a pilot study commenced in Alexandria. [4]

Nigeria

Only a small fraction of Nigerians receive water from waterworks, so water fluoridation would benefit only a few people. About 20% of water sources are naturally fluoridated to recommended levels, about 60% have fluoride below recommended levels, and the remainder are above recommended levels. [5]

South Africa

South Africa's Health Department recommends adding fluoridation chemicals to drinking water in some areas. It also advises removal of fluoride from drinking water (defluoridation) where the fluoride content is too high. [6] [7]

Legislation around mandatory fluoridation was introduced in 2002, but has been on hold since then pending further research after opposition from water companies, municipalities and the public. [8]

Asia

China

In China, water fluoridation began in 1965 in the urban area of Guangzhou. It was interrupted during 1976–1978 due to the shortage of sodium silico-fluoride. It was resumed only in the Fangcun district of the city, due to objections, and was halted in 1983. The fluoridation reduced the number of cavities, but increased dental fluorosis; the fluoride levels could have been set too high, and low-quality equipment led to inconsistent, and often excessive, fluoride concentrations. [9]

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, water is totally fluoridated, [10] at an average level of 0.49 mg/L [11]

Japan

Less than 1% of Japan practices water fluoridation. [12]

India

Water fluoridation is not practiced in India. [13] [14] Fluorosis is endemic in at least 20 states, including Uttaranchal, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. [15] The maximum permissible limit of fluoride in drinking water in India is 1.2 mg/L, [16] and the government has been obligated to install reverse osmosis water treatment plants to reduce fluoride levels from industrial waste and mineral deposits. [17]

Singapore

In 1956, Singapore was the first asian country to institute a water fluoridation program that covered 100% of the population. [18] [19] Water is fluoridated to a typical value of 0.4-0.6 mg per litre. [20]

Europe

Austria

Austria has never implemented fluoridation. [12]

Belgium

Belgium does not fluoridate its water supply, although legislation permits it. [12]

Czech Republic

Czech Republic ( Czechoslovakia respectively) started water fluoridation in 1958 in Tábor. After six years, 80% reduction of decay was asserted [ citation needed]. This led to widespread introduction of fluoridation. In Prague, fluoridation started in 1975. It was stopped in 1988 there and subsequently in the whole country too. Currently ( 2008) no water is fluoridated. [21] Fluoridated salt is available. [22]

Croatia

Croatia does not fluoridate its water. [23]

Denmark

Denmark does not fluoridate its water, although the National Health Board is in favour. [12]

Finland

The Finnish government supports fluoridation, although only one community of 70 000 people was fluoridated, Kuopio. [12] Kuopio stopped fluoridation in 1992. [24]

France

France fluoridates salt. [12]

Germany

Drinking water is not fluoridated in any part of Germany. The GDR used to fluoridate drinking water, but it was discontinued after the German reunification. [1]

Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland the majority of drinking water is fluoridated; 71% of the population in 2002 resided in fluoridated communities. [25] The fluoridation agent used is hydrofluosilicic acid (HFSA; H2SiF6). [26] In a 2002 public survey, 45% of respondents expressed some concern about fluoridation. [27]

In 1957, the Department of Health established a Fluorine Consultative Council which recommended fluoridation at 1.0 ppm of public water supplies, then accessed by c.50% of the population. [28] This was felt to be a much cheaper way of improving the quality of children's teeth than employing more dentists. [29] The ethical approval for this was given by the "Guild of Saints Luke, Cosmas and Damian", established by Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid. [28] This led to the Health (Fluoridation of Water Supplies) Act 1960, which mandated compulsory fluoridation by local authorities. [29] [30] The statutory instruments made in 1962–65 under the 1960 Act were separate for each local authority, setting the level of fluoride in drinking water to 0.8–1.0 ppm. [31] [32] The current regulations date from 2007, and set the level to 0.6–0.8 ppm, with a target value of 0.7 ppm. [33]

Implementation of fluoridation was held up by preliminary dental surveying and water testing, [34] and a court case, Ryan v. Attorney General. [35] In 1965, the Supreme Court rejected Gladys Ryan's claim that the Act violated the Constitution of Ireland's guarantee of the right to bodily integrity. [35] [36] By 1965, Greater Dublin's water was fluoridated; by 1973, other urban centres were. [37] Dental surveys of children from the 1950s to the 1990s showed marked reductions in cavities parallel to the spread of fluoridation. [38]

Netherlands

Water was fluoridated in large parts of the Netherlands from 1960 to 1973, when the High Council of The Netherlands declared fluoridation of drinking water unauthorized. [39] Dutch authorities had no legal basis adding chemicals to drinking water if they will not improve the safety as such. [4] Drinking water has not been fluoridated in any part of the Netherlands since 1973.

Spain

Around 10% of the population receives fluoridated water. [40]

Sweden

In 1952, Norrköping in Sweden became one of the first cities in Europe to fluoridate its water supply. [41] It was declared illegal by the Swedish Supreme Administrative Court in 1961, re-legalized in 1962 [42] and finally prohibited by the parliament in 1971, [43] after considerable debate. The parliament majority said that there were other and better ways of reducing tooth decay than water fluoridation. Four cities received permission to fluoridate tap water when it was legal. [41]: 56–57 An official commission was formed, which published its final report in 1981. They recommended other ways of reducing tooth decay (improving food and oral hygiene habits) instead of fluoridating tap water. They also found that many people found fluoridation to impinge upon personal liberty/freedom of choice by forcing them to be medicated, and that the long-term effects of fluoridation were insufficiently acknowledged. They also lacked a proper study on the effects of fluoridation on formula-fed infants. [41]: 29

Switzerland

In Switzerland since 1962 two fluoridation programmes had operated in tandem: water fluoridation in the City of Basel, and salt fluoridation in the rest of Switzerland (around 83% of domestic salt sold had fluoride added). However it became increasingly difficult to keep the two programmes separate. As a result some of the population of Basel were assumed to use both fluoridated salt and fluoridated water. In order to correct that situation, in April 2003 the State Parliament agreed to cease water fluoridation and officially expand salt fluoridation to Basel. [44]

United Kingdom

Around 10% of the population of the United Kingdom receives fluoridated water [40] about half a million people receive water that is naturally fluoridated with calcium fluoride which is different to sodium fluoride, and about 6 million total receive fluoridated water. [45] The All Party Parliamentary Group on Primary Care and Public Health recommended in April 2003 that fluoridation be introduced "as a legitimate and effective means of tackling dental health inequalities".[ citation needed] The Water Act 2003 required water suppliers to comply with requests from local health authorities to fluoridate their water. [45]

The following UK water utility companies fluoridate their supply:

- Anglian Water Services Ltd

- Northumbrian Water Ltd

- South Staffordshire Water plc

- Severn Trent plc

- United Utilities Water plc

Earlier schemes were undertaken in the Health Authority areas of Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Birmingham, Black Country, Cheshire, Merseyside, County Durham, Tees Valley, Cumbria, Lancashire, North, East Yorkshire, Northern Lincolnshire, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear, Shropshire, Staffordshire, Trent and West Midlands South whereby fluoridation was introduced progressively in the years between 1964 and 1988. [46]

The South Central Strategic Health Authority carried out the first public consultation under the Water Act 2003, and in 2009 its board voted to fluoridate water supplies in the Southampton area to address the high incidence of tooth decay in children there. [45] Surveys had found that the majority of surveyed Southampton residents opposed the plan, but the Southampton City Primary Care Trust decided that "public vote could not be the deciding factor". A judicial review has been initiated. [47] Fluoridation plans have been particularly controversial in the North West of England and have been delayed after a large increase on projected costs was revealled. [48]

The water supply in Northern Ireland has never been artificially fluoridated except in two small localities where fluoride was added to the water for about 30 years. By 1999, fluoridation ceased in those two areas, as well. Scotland's parliament rejected proposals to fluoridate public drinking water following a public consultation.[ citation needed]

Middle East

Israel

Water supply in Israel is artificially fluoridated since the 1970s. Settlements with more than 5000 citizens and settlements sharing water infrastructure with large settlements receive fluoridated water. About 67% of Israel's population receives fluoridated water. [49]

North America

Canada

The decision whether to fluoridate lies with local governments, with guidelines set by provincial, territorial, and federal governments. Brantford, Ontario became the first city in Canada to fluoridate its water supplies in 1945. [50] In 1955, Toronto approved water fluoridation, but delayed implementation of the program until 1963 due to a campaign against fluoridation by broadcaster Gordon Sinclair. [51] The city continues to fluoridate its water today. [52] In 2008 the recommended fluoride levels in Canada were reduced from 0.8–1.0 mg/L to 0.7 mg/L to minimize the risk of dental fluorosis. Ontario, Alberta, and Manitoba have the highest rates of fluoridation, about 70–75%. The lowest rates are in Quebec (about 6%), British Columbia (about 4%), and Newfoundland and Labrador (1.5%), with Nunavut and the Yukon having no fluoridation at all. [50] Overall, about 45% of the Canadian population had access to fluoridated water supplies in 2007. [50] A 2008 survey found that about half of Canadian adults knew about fluoridation, and of these, 62% supported the idea. [53]

United States

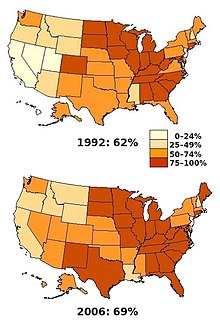

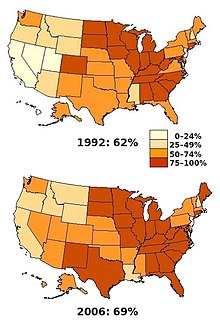

As of May 2000, 42 of the 50 largest U.S. cities had water fluoridation. [55] According to a 2002 study, [56] 67% of U.S. residents were living in communities with fluoridated water at that time. In 2010, a U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study determined that "40.7% of adolescents aged 12–15 had dental fluorosis [in 1999–2004]" [57]. In response, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services together with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency are proposing [58] to reduce the recommended level of fluoride in drinking water to the lowest end of the current range, 0.7 milligrams per liter of water (mg/L), from the previous recommended maximum of 1.2 mg/L. [59] This could effectively terminate municipal water fluoridation in areas where fluoride levels from mineral deposits and industrial pollution exceed the new recommendation. [60]

Australasia

Australia

Australia now has fluoridation in all states and territories.

Queensland - On 5 December 2007 Queensland Premier Anna Bligh announced fluoridation of most of Queensland's water supply will begin in 2008, making Queensland the last state to legally require the addition of fluoride to drinking water. [61] The Water Fluoridation Act 2008 was passed as promised, and requires the addition of fluoride to any "water supply supplying potable water to at least 1000 members of the public," unless an exemption is granted based on safety or naturally occurring levels that meet the required levels (ss 6 and 8). However, the towns of Biloela, Dalby, Gatton, Mareeba, Moranbah, and Townsville/ Thuringowa have been adding fluoride to their drinking water since 1972, though some of these towns stopped adding fluoride prior to the Water Fluoridation Act. [62] Additionally, several areas of Queensland, such as Julia Creek, Quilpie, Thargomindah and Adavale are known to have naturally occurring fluoride present in their drinking water, a characteristic that has been studied since the late 1920s. [63]

On May 2, 2009 an accident occurred at the North Pine Dam treatment plant where it was believed that 300,000 litres of contaminated water was pumped into up to 4000 homes in the northern suburbs of Brendale and Warner for three hours. Subsequent investigation showed that most of this water did not leave the drinking water treatment plant. The investigation also showed that while it was first believed the water contained 30 to 31 mg/L of fluoride instead of the maximum allowable 1.5 mg/L, the true value was between 17 and 19.6 mg/L [64] [65] Anna Bligh expressed her concerns stating "This is unacceptable and I, like other Queenslanders, have questions about it, and I'm not happy,". [66] [67]

Side effects in Queensland: There is a vocal minority [68] in Queensland that claims negative effects from the addition of fluoride to drinking water. To date there has been no evidence linking the addition of fluoride to the negative effects claimed by those opposed to fluoride within Queensland.

Claims about the negative effects of the addition of fluoride within Queensland are unsupported, as the addition of fluoride to drinking water supplies has only occurred in major metropolitan areas since late 2008, and no studies have been conducted to discern what effects have resulted specifically in Queensland as a consequence. For example, the claim that in 2008-2009 the Queensland Police recorded +40% increase in juvenile violence related crimes and all worst types of crimes increased more than the national average [ citation needed] might be linked to the addition of fluoride does not have merit. Such consequences could not have been possible given that fluoride was not in the water in Queensland long enough or in the amount necessary to cause any negative effect that might have contributed to the increase in violent crime. Such a claim links an event that shares the same time period and falsely associates a cause and effect between the two, also known as a Post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. Additionally, some anti-fluoridation scientists have claimed a negative effect cause by augmented accumulation of lead in the brain. According to Prof. Roger Masters' studies, lead accumulation is induced by the Silicofluorides used to fluoridate water which do not electrolise in F- and Si+ ions as simplistically described by fluoridation's supporters and government agencies. Again, such claims do not relate to Queensland as this research was conducted in 2001 based on surveys of populations in the United States [69] There have been no similar studies within Queensland. Between 2007 and 2010, Queensland Health recorded + 40% increase in diabetes [ citation needed] and in 2007 Queensland's dental health was at least better than Tasmania's in 2008 [ citation needed]; after fluoridation, Queensland's dental health considerably worsened despite the national consumes of sugar diminished 20% [ citation needed]. The substantial increase in diabetes cases has been associated by some independent researchers to the semi-unknown bio-dynamics of fluorinated ammino-acids that are stongly bipolar and super-hydrophobic[ citation needed]. The worsened dental health was eventually a simple effect of the increased number of people who did not regularly brush their teeth because wrongly thinking that fluoride ingestion could successfully replace oral hygiene after meals[ citation needed].

An exception exists in Western Australia where approximately 20,000 residents within the Busselton, Vasse and Wonnerup townsites, do not receive artificially fluoridated water. [70]

The first town to fluoridate the water supply in Australia was Beaconsfield, Tasmania in 1953. [71]

New Zealand

New Zealand has fluoridated water supplied to about half of the total population. [72] Christchurch is the only main centre not to have a fluoridated water supply. [73] The use of water fluoridation first began in New Zealand in Hastings in 1954. A Commission of Inquiry was held in 1957 and then its use rapidly expanded in the mid 1960s. [74] In a 2007 referendum about half of voters in the Central Otago, South Otago and the Southland Region did not want fluoridation [75] and voters in the Waitaki District were against water fluoridation for all Wards. [76] Ashburton and Greymouth also voted against fluoridation. [77]

South America

Brazil

Water fluoridation was first adopted in Brazil in the city of Baixo Guandu, ES, in 1953. [78] A 1974 federal law required new or enlarged water treatment plants to have fluoridation, and its availability was greatly expanded in the 1980s, with optimum fluoridation levels set at 0.8 mg/L. Today, the expansion of fluoridation in Brazil is a governmental priority; state-sponsored research points to a sharp correlation between the availability of fluoridation and benefits to human health. [79] Between 2005 and 2008, fluoridation became available to 7.6 million people in 503 municipalities. [79] As of 2008, 3,351 municipalities, 60.3% of total, adopted fluoridation, up from 2,466 in 2000. [80] The proportion of the national population affected is greater, because cities with fluoridation tend to be larger.

Chile

In Chile 70.5% of the population receive fluoridated water (10.1 million added by chemical means, 604,000 naturally occurring). [81]

References

- ^

a

b The British Fluoridation Society; The UK Public Health Association; The British Dental Association; The Faculty of Public Health (2004). "The extent of water fluoridation".

One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation (2nd ed.). Manchester: British Fluoridation Society. pp. 55–80.

ISBN

095476840X.

{{ cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^

a

b Cheng KK, Chalmers I, Sheldon TA (2007).

"Adding fluoride to water supplies". BMJ. 335 (7622): 699–702.

doi:

10.1136/bmj.39318.562951.BE.

PMC

2001050.

PMID

17916854.

{{ cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) -

^ Armfield JM (2007).

"When public action undermines public health: a critical examination of antifluoridationist literature". Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 4 (1): 25.

doi:

10.1186/1743-8462-4-25.

PMC

2222595.

PMID

18067684.

{{ cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI ( link) - ^ a b L.J.A. Damen, P. Nicolaï, J.L. Boxum, K.J. de Graaf, J.H. Jans, A.P. Klap, A.T. Marseille, A.R. Neerhof, B.K. Olivier, B.J. Schueler, F.R. Vermeer, R.L. Vucsán (2005) Bestuursrecht 1, 2de druk; Boom Uitgevers, Den Haag; 54-55 (ISBN 978-90-5454-537-8)

- ^ Akpata ES, Danfillo IS, Otoh EC, Mafeni JO. Geographical mapping of fluoride levels in drinking water sources in Nigeria [PDF]. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9(4):227–33.

- ^ "Water Fluoridation - The Facts", from South Africa's Department of Health website, page accessed April 29, 2006.

- ^ The Water Page - Rand Water and Fluoridation

- ^ http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?set_id=1&click_id=125&art_id=vn20030108054021972C918779

-

^ Petersen PE, Kwan S, Zhu L, Zhang BX, Bian JY (2008). "Effective use of fluorides in the People's Republic of China--a model for WHO Mega Country initiatives". Community Dental Health. 25 (4 Suppl 1): 257–67.

doi:

10.1922/CDH_2475Petersen11.

PMID

19202775.

{{ cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^ Water Treatment Process, Water Supplies Department, The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

- ^ Drinking Water Quality for the Period of April 2008 - March 2009, Water Supplies Department, The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

- ^ a b c d e f NCFPR. Fluoridation Facts: Antifluoride Assertion - "Advanced Countries Shun Fluoridation". Drawn from the ADA [www.ada.org/sections/newsAndEvents/pdfs/fluoridation_facts.pdf Fluoridation Facts] document. Cite error: The named reference "NCFPR" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Ingram, Colin. (2006). The Drinking Water Book. pp. 15-16

- ^ Control of Fluorosis in India

- ^ Fluoridation and Fluorosis Disaster - India: Fluoride in water takes its toll in Assam - La Leva di Archimede (ENG)

- ^ WHO | Naturally occurring hazards

- ^ http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-04-20/india/29450356_1_rivers-rivulets-industrial-effluents

-

^ Loh T (1996). "Thirty-eight years of water fluoridation--the Singapore scenario". Community Dental Health. 13 (Suppl 2): 47–50.

PMID

8897751.

{{ cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored ( help) -

^ Teo CS (1984). "Fluoridation of public water supplies in Singapore". Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 13 (2): 247–51.

PMID

6497322.

{{ cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored ( help) - ^ Water Treatment, Public Utility Board. http://www.pub.gov.sg/general/Pages/WaterTreatment.aspx

- ^ MEDICAL TRIBUNE CZ: Sláva a pád jedné preventivní metody

- ^ Malý zub taky zub aneb zoubky našich dětí IV.

- ^ Newspaper article in Vjesnik.hr

- ^ name=Caries Research Caries Occurrence in a Fluoridated and a Nonfluoridated Town in Finland: A Retrospective Study Using Longitudinal Data from Public Dental Records

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.76 - Dept of Health and Children - Ireland

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, pp.29–30

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.37

- ^ a b Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.71

- ^ a b Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.72

- ^ Health (Fluoridation of Water Supplies) Act, 1960, Irish Statute Book

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.170

- ^ A full list is in "Schedule 2: Revocations". S.I. No. 42 of 2007: Fluoridation of Water Supplies Regulations 2007. Irish Statute Book. 2 February 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ "S.I. No. 42 of 2007: Fluoridation of Water Supplies Regulations 2007". Irish Statute Book. 2 February 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.73

- ^ a b Ryan v. Attorney General [1965] IESC 1 (3 July 1965)

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, pp.74–76

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.76

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, pp.76–78

- ^ -Bram van der Lek, "De strijd tegen fluoridering", in De Gids, v.139, 1976

- ^

a

b Mullen J; European Association for Paediatric Dentistry (2005). "History of water fluoridation". British Dental Journal. 199 (7 Suppl): 1–4.

doi:

10.1038/sj.bdj.4812863.

PMID

16215546.

{{ cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored ( help) - ^

a

b

c Larsson, Gerhard (1981). Fluor i kariesförebyggande syfte - Betänkande av fluorberedningen (in Swedish). Stockholm: Statens offentliga utredningar / Socialdepartementet. p. 12. SOU 1981:32.

{{ cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) ( help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored ( help) - ^ "Fluoreringsfrågan avgjord". Västmanlands läns tidning (in Swedish). 1962-11-22.

- ^ "Stopp för fluor". Västmanlands läns tidning (in Swedish). 1971-11-19. p. 1.

- ^ J. MEYER and P. Wiehl in Schweiz Monatsschr. Zahnmed 2003; 113: 702 (in French) and 728-729 (in German)

- ^ a b c Gibson-Moore H (2009). "Water fluoridation for some—should it be for all?". Nutrition Bulletin. 34 (3): 291–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-3010.2009.01762.x.

- ^ British Medical Association

- ^ Southampton fluoridation challenge launched. (2009-6-30). Dentistry.co.uk.

- ^ Fluoride plan costs increase at lancashiretelegraph.co.uk

- ^ http://www.health.gov.il/pages/default.asp?maincat=73&catId=848&PageId=4497

- ^ a b c Rabb-Waytowich D (2009). "Water fluoridation in Canada: past and present" (PDF). J Can Dent Assoc. 75 (6): 451–4. PMID 19627654.

- ^ "Gordon Sinclair's rant", from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Archives website, page accessed March 27, 2006.

- ^ "Water supply - R. L. Clark Filtration Plant", from Toronto's website, page accessed March 27, 2006.

- ^ Quiñonez CR, Locker D (2009). "Public opinions on community water fluoridation". Can J Public Health. 100 (2): 96–100. PMID 19839282.

- ^ Klein RJ (2008-02-07). "Healthy People 2010 Progress Review, Focus Area 21, Oral Health". National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ The Benefits of Fluoride, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, accessed 19 March 2006.

- ^ Fluoridation Status: Percentage of U.S. Population on Public Water Supply Systems Receiving Fluoridated Water, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, accessed 19 March 2006.

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db53.pdf

- ^ http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2011pres/01/20110107a.html

- ^ http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2011/01/07/132735857/feds-lowering-fluoride-limits-in-water-to-avoid-damaging-kids-teeth

- ^ fluoridealert.org/re/thiessen-2-14-11.hhs.pdf

- ^ Qld to get fluoridated water - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

- ^ Impact Analysis of Water Fluoridation - December 2002, Jaguar Consulting

- ^ Interim Report of the Fluoride in Waters Survey Committee

- ^ Queensland Health Investigators Report: Water Fluoridation Incident, North Pine water treatment plant [1]

- ^ Investigation into the Fluoride Dosing Incident - North Pine Water Treatment Works - April 2009, Mark Pascoe

- ^ Courier Mail - Damage control after fluoride blunder hits homes

- ^ Courier Mail - Brisbane given Fluoride overdose on May 2

- ^ Surveys conducted over recent years by the Queensland Office of Economic and Statistical Research, the Local Government Association of Queensland, Central Queensland University and the Queensland Oral Health Alliance have consistently demonstrated that between 60% and 70% of Queenslanders support fluoridation.

- ^ Association of silicofluoride treated water with elevated blood lead. Masters, Coplan, Hone, Dykes. 2000

- ^ Busselton Water (Understanding our Natural Groundwater Resource)

-

^ Editors: Graham Aplin, S.G. Foster and Michael McKernan, ed. (1987). "Tasmania". Australians:Events and Places. Sydney, NSW, Australia: Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates. pp. page 366.

ISBN

0-521-34073-X.

{{ cite book}}:|editor=has generic name ( help);|pages=has extra text ( help) - ^ "Drinking Water Supplies of New Zealand by LA District". ESR Water Group. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

-

^ Newman, Sue (14 June 2005). "Christchurch targeted for new fluoridation drive". Ashburton Guardian.

{{ cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=( help) - ^ New Zealand Ministry of Health

- ^ "Voters say no to water fluoridation". The Southland Times. 3 November 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

-

^ "Waitaki District Council: all Wards with referendum vote NO to fluoridation". 18 October 2007.

{{ cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=( help); Missing or empty|url=( help) - ^ Keast, John (12 March 2007). "Ashburton fluoride bid fails" (PDF). The Press. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ [2]

- ^ a b [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ Information from the Oral Health Department of the Chilean Ministry of Health. December 2004.

Fishieman15 (

talk |

contribs) |

165.86.81.20 (

talk) |

||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

Side effects in Queensland: There is a vocal minority<ref>Surveys conducted over recent years by the Queensland Office of Economic and Statistical Research, the Local Government Association of Queensland, Central Queensland University and the Queensland Oral Health Alliance have consistently demonstrated that between 60% and 70% of Queenslanders support fluoridation.</ref> in Queensland that claims negative effects from the addition of fluoride to drinking water. To date there has been no evidence linking the addition of fluoride to the negative effects claimed by those opposed to fluoride within Queensland. |

Side effects in Queensland: There is a vocal minority<ref>Surveys conducted over recent years by the Queensland Office of Economic and Statistical Research, the Local Government Association of Queensland, Central Queensland University and the Queensland Oral Health Alliance have consistently demonstrated that between 60% and 70% of Queenslanders support fluoridation.</ref> in Queensland that claims negative effects from the addition of fluoride to drinking water. To date there has been no evidence linking the addition of fluoride to the negative effects claimed by those opposed to fluoride within Queensland. |

||

Claims about the negative effects of the addition of fluoride within Queensland are unsupported, as the addition of fluoride to drinking water supplies has only occurred in major metropolitan areas since late 2008, and no studies have been conducted to discern what effects have resulted specifically in Queensland as a consequence. For example, the claim that in 2008-2009 the Queensland Police recorded +40% increase in juvenile violence related crimes and all worst types of crimes increased more than the national average {{Citation needed}} might be linked to the addition of fluoride does not have merit |

Claims about the negative effects of the addition of fluoride within Queensland are unsupported, as the addition of fluoride to drinking water supplies has only occurred in major metropolitan areas since late 2008, and no studies have been conducted to discern what effects have resulted specifically in Queensland as a consequence. For example, the claim that in 2008-2009 the Queensland Police recorded +40% increase in juvenile violence related crimes and all worst types of crimes increased more than the national average {{Citation needed}} might be linked to the addition of fluoride does not have merit. Such consequences could not have been possible given that fluoride was not in the water in Queensland long enough or in the amount necessary to cause any negative effect that might have contributed to the increase in violent crime. Such a claim links an event that shares the same time period and falsely associates a cause and effect between the two, also known as a [[Post hoc ergo propter hoc]] fallacy. Additionally, some anti-fluoridation scientists have claimed a negative effect cause by augmented accumulation of lead in the brain. According to Prof. [[Roger Masters]]' studies, lead accumulation is induced by the Silicofluorides used to fluoridate water which do not electrolise in F- and Si+ ions as simplistically described by fluoridation's supporters and government agencies. Again, such claims do not relate to Queensland as this research was conducted in 2001 based on surveys of populations in the United States <ref>[http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/11233755 Association of silicofluoride treated water with elevated blood lead. Masters, Coplan, Hone, Dykes. 2000]</ref> There have been no similar studies within Queensland. Between 2007 and 2010, Queensland Health recorded + 40% increase in diabetes {{Citation needed}} and in 2007 Queensland's dental health was at least better than Tasmania's in 2008 {{Citation needed}}; after fluoridation, Queensland's dental health considerably worsened despite the national consumes of sugar diminished 20% {{Citation needed}}. The substantial increase in diabetes cases has been associated by some independent researchers to the semi-unknown bio-dynamics of fluorinated ammino-acids that are stongly bipolar and super-hydrophobic{{Citation needed}}. The worsened dental health was eventually a simple effect of the increased number of people who did not regularly brush their teeth because wrongly thinking that fluoride ingestion could successfully replace oral hygiene after meals{{Citation needed}}. |

||

An exception exists in [[Western Australia]] where approximately 20,000 residents within the [[Busselton]], [[Vasse]] and [[Wonnerup]] townsites, do not receive artificially fluoridated water.<ref>[http://www.busseltonwater.wa.gov.au/OurWater.aspx Busselton Water (Understanding our Natural Groundwater Resource)]</ref> |

An exception exists in [[Western Australia]] where approximately 20,000 residents within the [[Busselton]], [[Vasse]] and [[Wonnerup]] townsites, do not receive artificially fluoridated water.<ref>[http://www.busseltonwater.wa.gov.au/OurWater.aspx Busselton Water (Understanding our Natural Groundwater Resource)]</ref> |

||

Revision as of 00:25, 22 December 2011

Human or Artificial Fluoridation of water, salt, and milk varies from country to country. Water fluoridation has been introduced to varying degrees in many countries, including Australia, Brazil, Canada, Chile, Ireland, Malaysia, the U.S., and Vietnam, [1] and is used by 5.7% of people worldwide. [2] Continental Europe largely does not fluoridate water, although some of its countries fluoridate salt; locations have discontinued water fluoridation in Germany, the Netherlands, and other countries. [2] Although health and dental organizations support water fluoridation in the countries that practice water fluoridation, [3] there has been considerable opposition to water fluoridation whenever it is proposed.

Africa

Egypt

Egypt does not fluoridate water, although a pilot study commenced in Alexandria. [4]

Nigeria

Only a small fraction of Nigerians receive water from waterworks, so water fluoridation would benefit only a few people. About 20% of water sources are naturally fluoridated to recommended levels, about 60% have fluoride below recommended levels, and the remainder are above recommended levels. [5]

South Africa

South Africa's Health Department recommends adding fluoridation chemicals to drinking water in some areas. It also advises removal of fluoride from drinking water (defluoridation) where the fluoride content is too high. [6] [7]

Legislation around mandatory fluoridation was introduced in 2002, but has been on hold since then pending further research after opposition from water companies, municipalities and the public. [8]

Asia

China

In China, water fluoridation began in 1965 in the urban area of Guangzhou. It was interrupted during 1976–1978 due to the shortage of sodium silico-fluoride. It was resumed only in the Fangcun district of the city, due to objections, and was halted in 1983. The fluoridation reduced the number of cavities, but increased dental fluorosis; the fluoride levels could have been set too high, and low-quality equipment led to inconsistent, and often excessive, fluoride concentrations. [9]

Hong Kong

In Hong Kong, water is totally fluoridated, [10] at an average level of 0.49 mg/L [11]

Japan

Less than 1% of Japan practices water fluoridation. [12]

India

Water fluoridation is not practiced in India. [13] [14] Fluorosis is endemic in at least 20 states, including Uttaranchal, Jharkhand and Chhattisgarh. [15] The maximum permissible limit of fluoride in drinking water in India is 1.2 mg/L, [16] and the government has been obligated to install reverse osmosis water treatment plants to reduce fluoride levels from industrial waste and mineral deposits. [17]

Singapore

In 1956, Singapore was the first asian country to institute a water fluoridation program that covered 100% of the population. [18] [19] Water is fluoridated to a typical value of 0.4-0.6 mg per litre. [20]

Europe

Austria

Austria has never implemented fluoridation. [12]

Belgium

Belgium does not fluoridate its water supply, although legislation permits it. [12]

Czech Republic

Czech Republic ( Czechoslovakia respectively) started water fluoridation in 1958 in Tábor. After six years, 80% reduction of decay was asserted [ citation needed]. This led to widespread introduction of fluoridation. In Prague, fluoridation started in 1975. It was stopped in 1988 there and subsequently in the whole country too. Currently ( 2008) no water is fluoridated. [21] Fluoridated salt is available. [22]

Croatia

Croatia does not fluoridate its water. [23]

Denmark

Denmark does not fluoridate its water, although the National Health Board is in favour. [12]

Finland

The Finnish government supports fluoridation, although only one community of 70 000 people was fluoridated, Kuopio. [12] Kuopio stopped fluoridation in 1992. [24]

France

France fluoridates salt. [12]

Germany

Drinking water is not fluoridated in any part of Germany. The GDR used to fluoridate drinking water, but it was discontinued after the German reunification. [1]

Ireland

In the Republic of Ireland the majority of drinking water is fluoridated; 71% of the population in 2002 resided in fluoridated communities. [25] The fluoridation agent used is hydrofluosilicic acid (HFSA; H2SiF6). [26] In a 2002 public survey, 45% of respondents expressed some concern about fluoridation. [27]

In 1957, the Department of Health established a Fluorine Consultative Council which recommended fluoridation at 1.0 ppm of public water supplies, then accessed by c.50% of the population. [28] This was felt to be a much cheaper way of improving the quality of children's teeth than employing more dentists. [29] The ethical approval for this was given by the "Guild of Saints Luke, Cosmas and Damian", established by Catholic Archbishop of Dublin, John Charles McQuaid. [28] This led to the Health (Fluoridation of Water Supplies) Act 1960, which mandated compulsory fluoridation by local authorities. [29] [30] The statutory instruments made in 1962–65 under the 1960 Act were separate for each local authority, setting the level of fluoride in drinking water to 0.8–1.0 ppm. [31] [32] The current regulations date from 2007, and set the level to 0.6–0.8 ppm, with a target value of 0.7 ppm. [33]

Implementation of fluoridation was held up by preliminary dental surveying and water testing, [34] and a court case, Ryan v. Attorney General. [35] In 1965, the Supreme Court rejected Gladys Ryan's claim that the Act violated the Constitution of Ireland's guarantee of the right to bodily integrity. [35] [36] By 1965, Greater Dublin's water was fluoridated; by 1973, other urban centres were. [37] Dental surveys of children from the 1950s to the 1990s showed marked reductions in cavities parallel to the spread of fluoridation. [38]

Netherlands

Water was fluoridated in large parts of the Netherlands from 1960 to 1973, when the High Council of The Netherlands declared fluoridation of drinking water unauthorized. [39] Dutch authorities had no legal basis adding chemicals to drinking water if they will not improve the safety as such. [4] Drinking water has not been fluoridated in any part of the Netherlands since 1973.

Spain

Around 10% of the population receives fluoridated water. [40]

Sweden

In 1952, Norrköping in Sweden became one of the first cities in Europe to fluoridate its water supply. [41] It was declared illegal by the Swedish Supreme Administrative Court in 1961, re-legalized in 1962 [42] and finally prohibited by the parliament in 1971, [43] after considerable debate. The parliament majority said that there were other and better ways of reducing tooth decay than water fluoridation. Four cities received permission to fluoridate tap water when it was legal. [41]: 56–57 An official commission was formed, which published its final report in 1981. They recommended other ways of reducing tooth decay (improving food and oral hygiene habits) instead of fluoridating tap water. They also found that many people found fluoridation to impinge upon personal liberty/freedom of choice by forcing them to be medicated, and that the long-term effects of fluoridation were insufficiently acknowledged. They also lacked a proper study on the effects of fluoridation on formula-fed infants. [41]: 29

Switzerland

In Switzerland since 1962 two fluoridation programmes had operated in tandem: water fluoridation in the City of Basel, and salt fluoridation in the rest of Switzerland (around 83% of domestic salt sold had fluoride added). However it became increasingly difficult to keep the two programmes separate. As a result some of the population of Basel were assumed to use both fluoridated salt and fluoridated water. In order to correct that situation, in April 2003 the State Parliament agreed to cease water fluoridation and officially expand salt fluoridation to Basel. [44]

United Kingdom

Around 10% of the population of the United Kingdom receives fluoridated water [40] about half a million people receive water that is naturally fluoridated with calcium fluoride which is different to sodium fluoride, and about 6 million total receive fluoridated water. [45] The All Party Parliamentary Group on Primary Care and Public Health recommended in April 2003 that fluoridation be introduced "as a legitimate and effective means of tackling dental health inequalities".[ citation needed] The Water Act 2003 required water suppliers to comply with requests from local health authorities to fluoridate their water. [45]

The following UK water utility companies fluoridate their supply:

- Anglian Water Services Ltd

- Northumbrian Water Ltd

- South Staffordshire Water plc

- Severn Trent plc

- United Utilities Water plc

Earlier schemes were undertaken in the Health Authority areas of Bedfordshire, Hertfordshire, Birmingham, Black Country, Cheshire, Merseyside, County Durham, Tees Valley, Cumbria, Lancashire, North, East Yorkshire, Northern Lincolnshire, Northumberland, Tyne and Wear, Shropshire, Staffordshire, Trent and West Midlands South whereby fluoridation was introduced progressively in the years between 1964 and 1988. [46]

The South Central Strategic Health Authority carried out the first public consultation under the Water Act 2003, and in 2009 its board voted to fluoridate water supplies in the Southampton area to address the high incidence of tooth decay in children there. [45] Surveys had found that the majority of surveyed Southampton residents opposed the plan, but the Southampton City Primary Care Trust decided that "public vote could not be the deciding factor". A judicial review has been initiated. [47] Fluoridation plans have been particularly controversial in the North West of England and have been delayed after a large increase on projected costs was revealled. [48]

The water supply in Northern Ireland has never been artificially fluoridated except in two small localities where fluoride was added to the water for about 30 years. By 1999, fluoridation ceased in those two areas, as well. Scotland's parliament rejected proposals to fluoridate public drinking water following a public consultation.[ citation needed]

Middle East

Israel

Water supply in Israel is artificially fluoridated since the 1970s. Settlements with more than 5000 citizens and settlements sharing water infrastructure with large settlements receive fluoridated water. About 67% of Israel's population receives fluoridated water. [49]

North America

Canada

The decision whether to fluoridate lies with local governments, with guidelines set by provincial, territorial, and federal governments. Brantford, Ontario became the first city in Canada to fluoridate its water supplies in 1945. [50] In 1955, Toronto approved water fluoridation, but delayed implementation of the program until 1963 due to a campaign against fluoridation by broadcaster Gordon Sinclair. [51] The city continues to fluoridate its water today. [52] In 2008 the recommended fluoride levels in Canada were reduced from 0.8–1.0 mg/L to 0.7 mg/L to minimize the risk of dental fluorosis. Ontario, Alberta, and Manitoba have the highest rates of fluoridation, about 70–75%. The lowest rates are in Quebec (about 6%), British Columbia (about 4%), and Newfoundland and Labrador (1.5%), with Nunavut and the Yukon having no fluoridation at all. [50] Overall, about 45% of the Canadian population had access to fluoridated water supplies in 2007. [50] A 2008 survey found that about half of Canadian adults knew about fluoridation, and of these, 62% supported the idea. [53]

United States

As of May 2000, 42 of the 50 largest U.S. cities had water fluoridation. [55] According to a 2002 study, [56] 67% of U.S. residents were living in communities with fluoridated water at that time. In 2010, a U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study determined that "40.7% of adolescents aged 12–15 had dental fluorosis [in 1999–2004]" [57]. In response, the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services together with the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency are proposing [58] to reduce the recommended level of fluoride in drinking water to the lowest end of the current range, 0.7 milligrams per liter of water (mg/L), from the previous recommended maximum of 1.2 mg/L. [59] This could effectively terminate municipal water fluoridation in areas where fluoride levels from mineral deposits and industrial pollution exceed the new recommendation. [60]

Australasia

Australia

Australia now has fluoridation in all states and territories.

Queensland - On 5 December 2007 Queensland Premier Anna Bligh announced fluoridation of most of Queensland's water supply will begin in 2008, making Queensland the last state to legally require the addition of fluoride to drinking water. [61] The Water Fluoridation Act 2008 was passed as promised, and requires the addition of fluoride to any "water supply supplying potable water to at least 1000 members of the public," unless an exemption is granted based on safety or naturally occurring levels that meet the required levels (ss 6 and 8). However, the towns of Biloela, Dalby, Gatton, Mareeba, Moranbah, and Townsville/ Thuringowa have been adding fluoride to their drinking water since 1972, though some of these towns stopped adding fluoride prior to the Water Fluoridation Act. [62] Additionally, several areas of Queensland, such as Julia Creek, Quilpie, Thargomindah and Adavale are known to have naturally occurring fluoride present in their drinking water, a characteristic that has been studied since the late 1920s. [63]

On May 2, 2009 an accident occurred at the North Pine Dam treatment plant where it was believed that 300,000 litres of contaminated water was pumped into up to 4000 homes in the northern suburbs of Brendale and Warner for three hours. Subsequent investigation showed that most of this water did not leave the drinking water treatment plant. The investigation also showed that while it was first believed the water contained 30 to 31 mg/L of fluoride instead of the maximum allowable 1.5 mg/L, the true value was between 17 and 19.6 mg/L [64] [65] Anna Bligh expressed her concerns stating "This is unacceptable and I, like other Queenslanders, have questions about it, and I'm not happy,". [66] [67]

Side effects in Queensland: There is a vocal minority [68] in Queensland that claims negative effects from the addition of fluoride to drinking water. To date there has been no evidence linking the addition of fluoride to the negative effects claimed by those opposed to fluoride within Queensland.

Claims about the negative effects of the addition of fluoride within Queensland are unsupported, as the addition of fluoride to drinking water supplies has only occurred in major metropolitan areas since late 2008, and no studies have been conducted to discern what effects have resulted specifically in Queensland as a consequence. For example, the claim that in 2008-2009 the Queensland Police recorded +40% increase in juvenile violence related crimes and all worst types of crimes increased more than the national average [ citation needed] might be linked to the addition of fluoride does not have merit. Such consequences could not have been possible given that fluoride was not in the water in Queensland long enough or in the amount necessary to cause any negative effect that might have contributed to the increase in violent crime. Such a claim links an event that shares the same time period and falsely associates a cause and effect between the two, also known as a Post hoc ergo propter hoc fallacy. Additionally, some anti-fluoridation scientists have claimed a negative effect cause by augmented accumulation of lead in the brain. According to Prof. Roger Masters' studies, lead accumulation is induced by the Silicofluorides used to fluoridate water which do not electrolise in F- and Si+ ions as simplistically described by fluoridation's supporters and government agencies. Again, such claims do not relate to Queensland as this research was conducted in 2001 based on surveys of populations in the United States [69] There have been no similar studies within Queensland. Between 2007 and 2010, Queensland Health recorded + 40% increase in diabetes [ citation needed] and in 2007 Queensland's dental health was at least better than Tasmania's in 2008 [ citation needed]; after fluoridation, Queensland's dental health considerably worsened despite the national consumes of sugar diminished 20% [ citation needed]. The substantial increase in diabetes cases has been associated by some independent researchers to the semi-unknown bio-dynamics of fluorinated ammino-acids that are stongly bipolar and super-hydrophobic[ citation needed]. The worsened dental health was eventually a simple effect of the increased number of people who did not regularly brush their teeth because wrongly thinking that fluoride ingestion could successfully replace oral hygiene after meals[ citation needed].

An exception exists in Western Australia where approximately 20,000 residents within the Busselton, Vasse and Wonnerup townsites, do not receive artificially fluoridated water. [70]

The first town to fluoridate the water supply in Australia was Beaconsfield, Tasmania in 1953. [71]

New Zealand

New Zealand has fluoridated water supplied to about half of the total population. [72] Christchurch is the only main centre not to have a fluoridated water supply. [73] The use of water fluoridation first began in New Zealand in Hastings in 1954. A Commission of Inquiry was held in 1957 and then its use rapidly expanded in the mid 1960s. [74] In a 2007 referendum about half of voters in the Central Otago, South Otago and the Southland Region did not want fluoridation [75] and voters in the Waitaki District were against water fluoridation for all Wards. [76] Ashburton and Greymouth also voted against fluoridation. [77]

South America

Brazil

Water fluoridation was first adopted in Brazil in the city of Baixo Guandu, ES, in 1953. [78] A 1974 federal law required new or enlarged water treatment plants to have fluoridation, and its availability was greatly expanded in the 1980s, with optimum fluoridation levels set at 0.8 mg/L. Today, the expansion of fluoridation in Brazil is a governmental priority; state-sponsored research points to a sharp correlation between the availability of fluoridation and benefits to human health. [79] Between 2005 and 2008, fluoridation became available to 7.6 million people in 503 municipalities. [79] As of 2008, 3,351 municipalities, 60.3% of total, adopted fluoridation, up from 2,466 in 2000. [80] The proportion of the national population affected is greater, because cities with fluoridation tend to be larger.

Chile

In Chile 70.5% of the population receive fluoridated water (10.1 million added by chemical means, 604,000 naturally occurring). [81]

References

- ^

a

b The British Fluoridation Society; The UK Public Health Association; The British Dental Association; The Faculty of Public Health (2004). "The extent of water fluoridation".

One in a Million: The facts about water fluoridation (2nd ed.). Manchester: British Fluoridation Society. pp. 55–80.

ISBN

095476840X.

{{ cite book}}: External link in|chapterurl=|chapterurl=ignored (|chapter-url=suggested) ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^

a

b Cheng KK, Chalmers I, Sheldon TA (2007).

"Adding fluoride to water supplies". BMJ. 335 (7622): 699–702.

doi:

10.1136/bmj.39318.562951.BE.

PMC

2001050.

PMID

17916854.

{{ cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) -

^ Armfield JM (2007).

"When public action undermines public health: a critical examination of antifluoridationist literature". Aust New Zealand Health Policy. 4 (1): 25.

doi:

10.1186/1743-8462-4-25.

PMC

2222595.

PMID

18067684.

{{ cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI ( link) - ^ a b L.J.A. Damen, P. Nicolaï, J.L. Boxum, K.J. de Graaf, J.H. Jans, A.P. Klap, A.T. Marseille, A.R. Neerhof, B.K. Olivier, B.J. Schueler, F.R. Vermeer, R.L. Vucsán (2005) Bestuursrecht 1, 2de druk; Boom Uitgevers, Den Haag; 54-55 (ISBN 978-90-5454-537-8)

- ^ Akpata ES, Danfillo IS, Otoh EC, Mafeni JO. Geographical mapping of fluoride levels in drinking water sources in Nigeria [PDF]. Afr Health Sci. 2009;9(4):227–33.

- ^ "Water Fluoridation - The Facts", from South Africa's Department of Health website, page accessed April 29, 2006.

- ^ The Water Page - Rand Water and Fluoridation

- ^ http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?set_id=1&click_id=125&art_id=vn20030108054021972C918779

-

^ Petersen PE, Kwan S, Zhu L, Zhang BX, Bian JY (2008). "Effective use of fluorides in the People's Republic of China--a model for WHO Mega Country initiatives". Community Dental Health. 25 (4 Suppl 1): 257–67.

doi:

10.1922/CDH_2475Petersen11.

PMID

19202775.

{{ cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^ Water Treatment Process, Water Supplies Department, The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

- ^ Drinking Water Quality for the Period of April 2008 - March 2009, Water Supplies Department, The Government of Hong Kong Special Administrative Region.

- ^ a b c d e f NCFPR. Fluoridation Facts: Antifluoride Assertion - "Advanced Countries Shun Fluoridation". Drawn from the ADA [www.ada.org/sections/newsAndEvents/pdfs/fluoridation_facts.pdf Fluoridation Facts] document. Cite error: The named reference "NCFPR" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ Ingram, Colin. (2006). The Drinking Water Book. pp. 15-16

- ^ Control of Fluorosis in India

- ^ Fluoridation and Fluorosis Disaster - India: Fluoride in water takes its toll in Assam - La Leva di Archimede (ENG)

- ^ WHO | Naturally occurring hazards

- ^ http://articles.timesofindia.indiatimes.com/2011-04-20/india/29450356_1_rivers-rivulets-industrial-effluents

-

^ Loh T (1996). "Thirty-eight years of water fluoridation--the Singapore scenario". Community Dental Health. 13 (Suppl 2): 47–50.

PMID

8897751.

{{ cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored ( help) -

^ Teo CS (1984). "Fluoridation of public water supplies in Singapore". Annals of the Academy of Medicine, Singapore. 13 (2): 247–51.

PMID

6497322.

{{ cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored ( help) - ^ Water Treatment, Public Utility Board. http://www.pub.gov.sg/general/Pages/WaterTreatment.aspx

- ^ MEDICAL TRIBUNE CZ: Sláva a pád jedné preventivní metody

- ^ Malý zub taky zub aneb zoubky našich dětí IV.

- ^ Newspaper article in Vjesnik.hr

- ^ name=Caries Research Caries Occurrence in a Fluoridated and a Nonfluoridated Town in Finland: A Retrospective Study Using Longitudinal Data from Public Dental Records

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.76 - Dept of Health and Children - Ireland

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, pp.29–30

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.37

- ^ a b Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.71

- ^ a b Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.72

- ^ Health (Fluoridation of Water Supplies) Act, 1960, Irish Statute Book

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.170

- ^ A full list is in "Schedule 2: Revocations". S.I. No. 42 of 2007: Fluoridation of Water Supplies Regulations 2007. Irish Statute Book. 2 February 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ "S.I. No. 42 of 2007: Fluoridation of Water Supplies Regulations 2007". Irish Statute Book. 2 February 2007. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.73

- ^ a b Ryan v. Attorney General [1965] IESC 1 (3 July 1965)

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, pp.74–76

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, p.76

- ^ Report of the Forum on Fluoridation 2002, pp.76–78

- ^ -Bram van der Lek, "De strijd tegen fluoridering", in De Gids, v.139, 1976

- ^

a

b Mullen J; European Association for Paediatric Dentistry (2005). "History of water fluoridation". British Dental Journal. 199 (7 Suppl): 1–4.

doi:

10.1038/sj.bdj.4812863.

PMID

16215546.

{{ cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|month=ignored ( help) - ^

a

b

c Larsson, Gerhard (1981). Fluor i kariesförebyggande syfte - Betänkande av fluorberedningen (in Swedish). Stockholm: Statens offentliga utredningar / Socialdepartementet. p. 12. SOU 1981:32.

{{ cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) ( help); Unknown parameter|month=ignored ( help) - ^ "Fluoreringsfrågan avgjord". Västmanlands läns tidning (in Swedish). 1962-11-22.

- ^ "Stopp för fluor". Västmanlands läns tidning (in Swedish). 1971-11-19. p. 1.

- ^ J. MEYER and P. Wiehl in Schweiz Monatsschr. Zahnmed 2003; 113: 702 (in French) and 728-729 (in German)

- ^ a b c Gibson-Moore H (2009). "Water fluoridation for some—should it be for all?". Nutrition Bulletin. 34 (3): 291–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-3010.2009.01762.x.

- ^ British Medical Association

- ^ Southampton fluoridation challenge launched. (2009-6-30). Dentistry.co.uk.

- ^ Fluoride plan costs increase at lancashiretelegraph.co.uk

- ^ http://www.health.gov.il/pages/default.asp?maincat=73&catId=848&PageId=4497

- ^ a b c Rabb-Waytowich D (2009). "Water fluoridation in Canada: past and present" (PDF). J Can Dent Assoc. 75 (6): 451–4. PMID 19627654.

- ^ "Gordon Sinclair's rant", from the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation Archives website, page accessed March 27, 2006.

- ^ "Water supply - R. L. Clark Filtration Plant", from Toronto's website, page accessed March 27, 2006.

- ^ Quiñonez CR, Locker D (2009). "Public opinions on community water fluoridation". Can J Public Health. 100 (2): 96–100. PMID 19839282.

- ^ Klein RJ (2008-02-07). "Healthy People 2010 Progress Review, Focus Area 21, Oral Health". National Center for Health Statistics. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- ^ The Benefits of Fluoride, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, accessed 19 March 2006.

- ^ Fluoridation Status: Percentage of U.S. Population on Public Water Supply Systems Receiving Fluoridated Water, from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website, accessed 19 March 2006.

- ^ http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db53.pdf

- ^ http://www.hhs.gov/news/press/2011pres/01/20110107a.html

- ^ http://www.npr.org/blogs/health/2011/01/07/132735857/feds-lowering-fluoride-limits-in-water-to-avoid-damaging-kids-teeth

- ^ fluoridealert.org/re/thiessen-2-14-11.hhs.pdf

- ^ Qld to get fluoridated water - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)

- ^ Impact Analysis of Water Fluoridation - December 2002, Jaguar Consulting

- ^ Interim Report of the Fluoride in Waters Survey Committee

- ^ Queensland Health Investigators Report: Water Fluoridation Incident, North Pine water treatment plant [1]

- ^ Investigation into the Fluoride Dosing Incident - North Pine Water Treatment Works - April 2009, Mark Pascoe

- ^ Courier Mail - Damage control after fluoride blunder hits homes

- ^ Courier Mail - Brisbane given Fluoride overdose on May 2

- ^ Surveys conducted over recent years by the Queensland Office of Economic and Statistical Research, the Local Government Association of Queensland, Central Queensland University and the Queensland Oral Health Alliance have consistently demonstrated that between 60% and 70% of Queenslanders support fluoridation.

- ^ Association of silicofluoride treated water with elevated blood lead. Masters, Coplan, Hone, Dykes. 2000

- ^ Busselton Water (Understanding our Natural Groundwater Resource)

-

^ Editors: Graham Aplin, S.G. Foster and Michael McKernan, ed. (1987). "Tasmania". Australians:Events and Places. Sydney, NSW, Australia: Fairfax, Syme & Weldon Associates. pp. page 366.

ISBN

0-521-34073-X.

{{ cite book}}:|editor=has generic name ( help);|pages=has extra text ( help) - ^ "Drinking Water Supplies of New Zealand by LA District". ESR Water Group. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

-

^ Newman, Sue (14 June 2005). "Christchurch targeted for new fluoridation drive". Ashburton Guardian.

{{ cite news}}:|access-date=requires|url=( help) - ^ New Zealand Ministry of Health

- ^ "Voters say no to water fluoridation". The Southland Times. 3 November 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

-

^ "Waitaki District Council: all Wards with referendum vote NO to fluoridation". 18 October 2007.

{{ cite web}}:|access-date=requires|url=( help); Missing or empty|url=( help) - ^ Keast, John (12 March 2007). "Ashburton fluoride bid fails" (PDF). The Press. Retrieved 29 January 2011.

- ^ [2]

- ^ a b [3]

- ^ [4]

- ^ Information from the Oral Health Department of the Chilean Ministry of Health. December 2004.