Basic concepts

Meaning

Semantics studies meaning in language, which is limited to the meaning of linguistic expressions. It concerns how signs are interpreted and what information they contain. An example is the meaning of words provided in dictionary definitions by giving synonymous expressions or paraphrases, like defining the meaning of the term ram as adult male sheep. [1] There are many forms of non-linguistic meaning that are not examined by semantics. Actions and policies can have meaning in relation to the goal they serve. Fields like religion and spirituality are interested in the meaning of life, which is about finding a purpose in life or the significance of existence in general. [2]

Linguistic meaning can be analyzed on different levels. Word meaning is studied by lexical semantics and investigates the denotation of individual words. It is often related to concepts of entities, like the word dog is associated with the concept of a four-legged domestic animal. Sentence meaning falls into the field of phrasal semantics and concerns the denotation of full sentences. It usually expresses a concept applying to a type of situation, as in the sentence "the dog has ruined my blue skirt". [3] The term proposition is often used to refer to the meaning of sentences. [4] Different sentences can express the same proposition, like the English sentence "the tree is green" and the German sentence "der Baum ist grün". [5] Utterance meaning is studied by pragmatics and is about the meaning of an expression on a particular occasion. Sentence meaning and utterance meaning come apart in cases where expressions are used in a non-literal way, as is often the case with irony. [6]

Semantics is primarily interested in the public or objective meaning that expressions have, like the meaning found in general dictionary definitions. Speaker meaning, by contrast, is the private or subjective meaning that individuals associate with expressions. It can diverge from literal meaning, like when a person associates the word needle with pain or drugs. [7]

Sense and reference

Meaning is often analyzed in terms of sense and reference, [9] also referred to as intension and extension or connotation and denotation. [10] The referent of an expression is the object to which the expression points. The sense of an expression is the way in which it refers to that object or how the object is interpreted. For example, the expressions morning star and evening star refer to the same planet, just like the expressions 2 + 2 and 3 + 1 refer to the same number. The meanings of these expressions differ not on the level of reference but on the level of sense. [11]

Sense is sometimes understood as an mediating entity that helps people relate linguistic expressions to the external world. According to this view, the sense of an expression corresponds to the mental phenomena in the form of concepts and ideas associated with this term. Through them, people can identify which objects it refers to. [12] Some semanticists focus primarily on sense or primarily on reference in their analysis of meaning. [13] To grasp the full meaning of an expression, it is usually necessary to understand both to what entities in the world it refers and how it describes them. [14]

The distinction between sense and reference can explain identity statements, which can be used to show how two expressions with a different sense have the same referent. For instance, the sentence "the morning star is the evening star" is informative and people can learn something from it. The sentence "the morning star is the morning star", by contrast, is an uninformative tautology since the expressions are identical not only on the level of reference but also on the level of sense. [15]

Compositionality

Compositionality is a key aspect of how languages construct meaning. It is the idea that the meaning of a complex expression is a function of the meanings of its parts. It is possible to understand the meaning of the sentence "Zuzana owns a dog" by understanding what the words Zuzana, owns, a and dog mean and how they are combined. [16] In this regard, the meaning of complex expressions like sentences is different from word meaning since it is normally not possible to deduce what a word means by looking at its letters and one needs to consult a dictionary instead. [17]

Compositionality is often used to explain how people can formulate and understand an almost infinite number of meanings even though the amount of words and cognitive resources is finite. Many sentences that people read are sentences that they have never seen before and they are nonetheless able to understand them. [18]

When interpreted in a strong sense, the principle of compositionality states that the meaning of complex expressions is not just affected by its parts and how they are combined but fully determined this way. It is controversial whether this claim is correct or whether additional aspects influence meaning. For example, context may affect the meaning of expressions, and idioms, like kick the bucket, carry figurative or non-literal meanings that are not directly reducible to the meanings of their parts. [19]

Truth and truth conditions

Truth is a property of statements that accurately present the world and true statements are in accord with reality. Whether a statement is true usually depends on the relation between the statement and the rest of the world. The truth conditions of a statement are the way the world needs to be for the statement to be true. For example, it belongs to the truth conditions of the sentence "it is raining outside" that rain drops are falling from the sky. The sentence is true if it is used in a situation in which the truth conditions are fulfilled, i.e., if there is actually rain outside. [20]

Truth conditions play a central role in semantics and some theories rely exclusively on truth conditions to analyze meaning. To understand a statement usually implies that one has an idea about the conditions under which it would be true. This can happen even if one does not know whether the conditions are fulfilled. [21]

Semiotic triangle

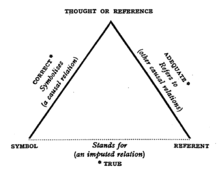

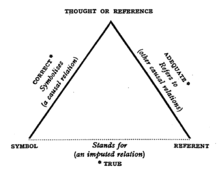

The semiotic triangle, also called the triangle of meaning, is a model used to explain the relation between language, language users, and the world, represented in the model as Symbol, Thought or Reference, and Referent. The symbol is a linguistic signifier, either in its spoken or written form. The central idea of the model is that there is no direct relation between a linguistic expression and what it refers to, as was assumed by earlier diadic models. This is expressed in the diagram by the dotted line between symbol and referent. [22]

The model holds instead that the relation between the two is mediated through a third component. For example, the term apple stands for a type of fruit but there is no direct connection between this string of letters and the corresponding physical object. The relation is only established indirectly through the mind of the language user. When they see the symbol, it evokes a mental image or a concept, which establishes the connection to the physical object. This process is only possible if the language user learned the meaning of the symbol before. The meaning of a specific symbol is governed by the conventions of a particular language. The same symbol may refer to one object in one language, to a another object in a different language, and to no object in another language. [23]

Others

Many other concepts are used to describe semantic phenomena. The semantic role of an expression is the function it fulfills in a sentence. In the sentence "the boy kicked the ball", the boy has the role of the agent who performs an action. The ball is the theme or patient of this action as something that does not act itself but is involved in or affected by the action. The same entity can be both agent and patient, like when someone cuts themselves. An entity has the semantic role of an instrument if it was used to perform the action, for instance, when cutting something with a knife then the knife is the instrument. For some sentences, no action is described but an experience takes place, like when a girl sees a bird. In this case, the girl has the role of the experiencer. Other common semantic roles are location, source, goal, beneficiary, and stimulus. [24]

Lexical relations describe how words stand to one another. Two words are synonyms if they share the same or a very similar meaning, like car and automobile or buy and purchase. Antonyms have opposite meanings, as the contrast between alive and dead or fast and slow. One term is a hyponym of another term if the meaning of the first term is included in the meaning of the second term. For example, ant is a hyponym of insect. A prototype is a hyponym that has characteristic features of the type it belongs to. A robin is a prototype of a bird but a penguin is not. Two words with the same pronunciation are homophones like flour and flower, while two words with the same spelling are homonyms, like the bank of a river in contrast to a bank as a financial institution. [a] Hyponymy is closely related to meronymy, which describes the relation between part and whole. For instance, wheel is a meronym of car. Polysemy is the capacity of a word to carry various related meanings, like the word head, which can refer to the topmost part of the human body or the top-ranking person in an organization. [26] An expression is ambiguous if it has more than one possible meaning. In some cases, it is possible to disambiguate them to discern the intended meaning. [27]

The meaning of words can often be subdivided into meaning components called semantic features. The word horse has the semantic feature animate but lacks the semantic feature human. It may not always be possible to fully reconstruct the meaning of a word by identifying all its semantic features. [28]

A semantic or lexical field is a group of words that are all related to the same activity or subject. For instance, the semantic field of cooking includes words like bake, boil, spice, and pan. [29]

Semanticists commonly distinguish the language they study, called object language, from the language they use to express their findings, called metalanguage. When a professor uses Japanese to teach their student how to interpret the language of first-order logic then the language of first-order logic is the object language and Japanese is the metalanguage. The same language may occupy the role of object language and metalanguage at the same time. This is the case in monolingual English dictionaries, in which both the entry term belonging to the object language and the definition text belonging to the metalanguage are taken from the English language. [30]

Sources

- Dummett, Michael (1981). Frege: Philosophy of Language. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-31931-8.

- Gamut, L. T. F. (1991). Logic, Language, and Meaning, Volume 1: Introduction to Logic. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-28084-4.

- Murphy, M. Lynne; Koskela, Anu (17 June 2010). Key Terms in Semantics. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84706-276-5.

- Reif, Monika; Polzenhagen, Frank (15 November 2023). Cultural Linguistics and Critical Discourse Studies. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-4952-4.

- Olkowski, Dorothea; Pirovolakis, Eftichis (31 January 2019). Deleuze and Guattari's Philosophy of Freedom: Freedom's Refrains. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-66352-9.

- Tondl, L. (2012). Problems of Semantics: A Contribution to the Analysis of the Language Science. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-009-8364-9.

- Dirven, René; Verspoor, Marjolijn (30 June 2004). Cognitive Exploration of Language and Linguistics: Second revised edition. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-9541-5.

- Palmer, Frank Robert (1976). Semantics: A New Outline. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521209277.

- Noth, Winfried (22 September 1990). Handbook of Semiotics. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20959-7.

- Kearns, Kate (16 September 2011). Semantics. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-71701-5.

- Blackburn, Simon (1 January 2008). "Truth Conditions". The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954143-0.

- Gregory, Howard (2016). Semantics. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415216109.

- Krifka, Manfred (4 September 2001). Wilson, Robert A.; Keil, Frank C. (eds.). The MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences (MITECS). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-73144-7.

- Pelletier, Francis Jeffry (1994). "The Principle of Semantic Compositionality". Topoi. doi: 10.1007/BF00763644.

- Szabó, Zoltán Gendler (2020). "Compositionality". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- Marti, Genoveva (1998). Sense and Reference. Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Leach, Stephen; Tartaglia, James (11 May 2018). "Postscript: The Blue Flower". The Meaning of Life and the Great Philosophers. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-38592-1.

- Abaza, Jack (16 November 2023). The Definitive Answer to the Meaning of Life. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 979-8-3852-0172-3.

- Cunningham, D. J. (2009). "Meaning, Sense, and Reference". In Allan, Keith (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Semantics. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-095969-6.

- Yule, George (2010). The Study of Language (4 ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76527-5.

- Löbner, Sebastian (2013). Understanding semantics (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-82673-0.

- Edmonds, P. (2009). "Disambiguation". In Allan, Keith (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Semantics. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-095969-6.

- Zalta, Edward N. (2022). "Gottlob Frege". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

-

^

- Cunningham 2009, pp. 530–531

- Yule 2010, pp. 113–114

-

^

- Leach & Tartaglia 2018, pp. 274–275

- Abaza 2023, p. 32

- Cunningham 2009, p. 526

- Löbner 2013, pp. 1–2

-

^

- Riemer 2010, pp. 21–22

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 5–6

- Löbner 2013, pp. 1–6, 18–21

- ^ Tondl 2012, p. 111

- ^ Olkowski & Pirovolakis 2019, pp. 65–66

-

^

- Riemer 2010, pp. 21–22

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 5–6

- Löbner 2013, pp. 1–6

- Saeed 2009, pp. 12–13

-

^

- Yule 2010, p. 113

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 5–6

- ^ Zalta 2022, § 1. Frege’s Life and Influences, § 3. Frege’s Philosophy of Language.

-

^

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 7–9

- Cunningham 2009, p. 526

- Saeed 2009, p. 46

-

^

- Cunningham 2009, p. 527

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 7–9

-

^

- Cunningham 2009, p. 526

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 7–9

-

^

- Marti 1998, Lead Section

- Riemer 2010, pp. 27–28

-

^

- Riemer 2010, pp. 25–28

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 7–9

- ^ Cunningham 2009, p. 531

- ^ Marti 1998, Lead Section

-

^

- Szabó 2020, Lead Section

- Pelletier 1994, p. 11–12

- Krifka 2001, p. 152

- ^ Löbner 2013, pp. 7–8, 10–12

-

^

- Szabó 2020, Lead Section

- Pelletier 1994, p. 11–12

- Krifka 2001, p. 152

-

^

- Szabó 2020, Lead Section

- Pelletier 1994, p. 11–12

- Krifka 2001, p. 152

-

^

- Gregory 2016, pp. 9–10

- Blackburn 2008, Truth Conditions

- Kearns 2011, pp. 8–10

-

^

- Gregory 2016, pp. 9–10

- Blackburn 2008, Truth Conditions

- Kearns 2011, pp. 8–10

-

^

- Palmer 1976, pp. 25–26

- Noth 1990, pp. 89–90

- Dirven & Verspoor 2004, pp. 28–29

- Riemer 2010, pp. 13–16

-

^

- Palmer 1976, pp. 25–26

- Noth 1990, pp. 89–90

- Dirven & Verspoor 2004, pp. 28–29

- Riemer 2010, pp. 13–16

-

^

- Yule 2010, pp. 115–116

- Saeed 2020, pp. 152–155

- ^ Saeed 2020, p. 63

-

^

- Yule 2010, pp. 116–120

- Saeed 2020, pp. 63–70

-

^

- Edmonds 2009, pp. 223–226

- Murphy & Koskela 2010, p. 57

- ^ Yule 2010, pp. 113–115

-

^

- Saeed 2020, p. 63

- Reif & Polzenhagen 2023, pp. 129–130

-

^

- Riemer 2010, pp. 22–23

- Gamut 1991, pp. 142–143

- Dummett 1981, p. 106

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the

help page).

Basic concepts

Meaning

Semantics studies meaning in language, which is limited to the meaning of linguistic expressions. It concerns how signs are interpreted and what information they contain. An example is the meaning of words provided in dictionary definitions by giving synonymous expressions or paraphrases, like defining the meaning of the term ram as adult male sheep. [1] There are many forms of non-linguistic meaning that are not examined by semantics. Actions and policies can have meaning in relation to the goal they serve. Fields like religion and spirituality are interested in the meaning of life, which is about finding a purpose in life or the significance of existence in general. [2]

Linguistic meaning can be analyzed on different levels. Word meaning is studied by lexical semantics and investigates the denotation of individual words. It is often related to concepts of entities, like the word dog is associated with the concept of a four-legged domestic animal. Sentence meaning falls into the field of phrasal semantics and concerns the denotation of full sentences. It usually expresses a concept applying to a type of situation, as in the sentence "the dog has ruined my blue skirt". [3] The term proposition is often used to refer to the meaning of sentences. [4] Different sentences can express the same proposition, like the English sentence "the tree is green" and the German sentence "der Baum ist grün". [5] Utterance meaning is studied by pragmatics and is about the meaning of an expression on a particular occasion. Sentence meaning and utterance meaning come apart in cases where expressions are used in a non-literal way, as is often the case with irony. [6]

Semantics is primarily interested in the public or objective meaning that expressions have, like the meaning found in general dictionary definitions. Speaker meaning, by contrast, is the private or subjective meaning that individuals associate with expressions. It can diverge from literal meaning, like when a person associates the word needle with pain or drugs. [7]

Sense and reference

Meaning is often analyzed in terms of sense and reference, [9] also referred to as intension and extension or connotation and denotation. [10] The referent of an expression is the object to which the expression points. The sense of an expression is the way in which it refers to that object or how the object is interpreted. For example, the expressions morning star and evening star refer to the same planet, just like the expressions 2 + 2 and 3 + 1 refer to the same number. The meanings of these expressions differ not on the level of reference but on the level of sense. [11]

Sense is sometimes understood as an mediating entity that helps people relate linguistic expressions to the external world. According to this view, the sense of an expression corresponds to the mental phenomena in the form of concepts and ideas associated with this term. Through them, people can identify which objects it refers to. [12] Some semanticists focus primarily on sense or primarily on reference in their analysis of meaning. [13] To grasp the full meaning of an expression, it is usually necessary to understand both to what entities in the world it refers and how it describes them. [14]

The distinction between sense and reference can explain identity statements, which can be used to show how two expressions with a different sense have the same referent. For instance, the sentence "the morning star is the evening star" is informative and people can learn something from it. The sentence "the morning star is the morning star", by contrast, is an uninformative tautology since the expressions are identical not only on the level of reference but also on the level of sense. [15]

Compositionality

Compositionality is a key aspect of how languages construct meaning. It is the idea that the meaning of a complex expression is a function of the meanings of its parts. It is possible to understand the meaning of the sentence "Zuzana owns a dog" by understanding what the words Zuzana, owns, a and dog mean and how they are combined. [16] In this regard, the meaning of complex expressions like sentences is different from word meaning since it is normally not possible to deduce what a word means by looking at its letters and one needs to consult a dictionary instead. [17]

Compositionality is often used to explain how people can formulate and understand an almost infinite number of meanings even though the amount of words and cognitive resources is finite. Many sentences that people read are sentences that they have never seen before and they are nonetheless able to understand them. [18]

When interpreted in a strong sense, the principle of compositionality states that the meaning of complex expressions is not just affected by its parts and how they are combined but fully determined this way. It is controversial whether this claim is correct or whether additional aspects influence meaning. For example, context may affect the meaning of expressions, and idioms, like kick the bucket, carry figurative or non-literal meanings that are not directly reducible to the meanings of their parts. [19]

Truth and truth conditions

Truth is a property of statements that accurately present the world and true statements are in accord with reality. Whether a statement is true usually depends on the relation between the statement and the rest of the world. The truth conditions of a statement are the way the world needs to be for the statement to be true. For example, it belongs to the truth conditions of the sentence "it is raining outside" that rain drops are falling from the sky. The sentence is true if it is used in a situation in which the truth conditions are fulfilled, i.e., if there is actually rain outside. [20]

Truth conditions play a central role in semantics and some theories rely exclusively on truth conditions to analyze meaning. To understand a statement usually implies that one has an idea about the conditions under which it would be true. This can happen even if one does not know whether the conditions are fulfilled. [21]

Semiotic triangle

The semiotic triangle, also called the triangle of meaning, is a model used to explain the relation between language, language users, and the world, represented in the model as Symbol, Thought or Reference, and Referent. The symbol is a linguistic signifier, either in its spoken or written form. The central idea of the model is that there is no direct relation between a linguistic expression and what it refers to, as was assumed by earlier diadic models. This is expressed in the diagram by the dotted line between symbol and referent. [22]

The model holds instead that the relation between the two is mediated through a third component. For example, the term apple stands for a type of fruit but there is no direct connection between this string of letters and the corresponding physical object. The relation is only established indirectly through the mind of the language user. When they see the symbol, it evokes a mental image or a concept, which establishes the connection to the physical object. This process is only possible if the language user learned the meaning of the symbol before. The meaning of a specific symbol is governed by the conventions of a particular language. The same symbol may refer to one object in one language, to a another object in a different language, and to no object in another language. [23]

Others

Many other concepts are used to describe semantic phenomena. The semantic role of an expression is the function it fulfills in a sentence. In the sentence "the boy kicked the ball", the boy has the role of the agent who performs an action. The ball is the theme or patient of this action as something that does not act itself but is involved in or affected by the action. The same entity can be both agent and patient, like when someone cuts themselves. An entity has the semantic role of an instrument if it was used to perform the action, for instance, when cutting something with a knife then the knife is the instrument. For some sentences, no action is described but an experience takes place, like when a girl sees a bird. In this case, the girl has the role of the experiencer. Other common semantic roles are location, source, goal, beneficiary, and stimulus. [24]

Lexical relations describe how words stand to one another. Two words are synonyms if they share the same or a very similar meaning, like car and automobile or buy and purchase. Antonyms have opposite meanings, as the contrast between alive and dead or fast and slow. One term is a hyponym of another term if the meaning of the first term is included in the meaning of the second term. For example, ant is a hyponym of insect. A prototype is a hyponym that has characteristic features of the type it belongs to. A robin is a prototype of a bird but a penguin is not. Two words with the same pronunciation are homophones like flour and flower, while two words with the same spelling are homonyms, like the bank of a river in contrast to a bank as a financial institution. [a] Hyponymy is closely related to meronymy, which describes the relation between part and whole. For instance, wheel is a meronym of car. Polysemy is the capacity of a word to carry various related meanings, like the word head, which can refer to the topmost part of the human body or the top-ranking person in an organization. [26] An expression is ambiguous if it has more than one possible meaning. In some cases, it is possible to disambiguate them to discern the intended meaning. [27]

The meaning of words can often be subdivided into meaning components called semantic features. The word horse has the semantic feature animate but lacks the semantic feature human. It may not always be possible to fully reconstruct the meaning of a word by identifying all its semantic features. [28]

A semantic or lexical field is a group of words that are all related to the same activity or subject. For instance, the semantic field of cooking includes words like bake, boil, spice, and pan. [29]

Semanticists commonly distinguish the language they study, called object language, from the language they use to express their findings, called metalanguage. When a professor uses Japanese to teach their student how to interpret the language of first-order logic then the language of first-order logic is the object language and Japanese is the metalanguage. The same language may occupy the role of object language and metalanguage at the same time. This is the case in monolingual English dictionaries, in which both the entry term belonging to the object language and the definition text belonging to the metalanguage are taken from the English language. [30]

Sources

- Dummett, Michael (1981). Frege: Philosophy of Language. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-31931-8.

- Gamut, L. T. F. (1991). Logic, Language, and Meaning, Volume 1: Introduction to Logic. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-28084-4.

- Murphy, M. Lynne; Koskela, Anu (17 June 2010). Key Terms in Semantics. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-84706-276-5.

- Reif, Monika; Polzenhagen, Frank (15 November 2023). Cultural Linguistics and Critical Discourse Studies. John Benjamins Publishing Company. ISBN 978-90-272-4952-4.

- Olkowski, Dorothea; Pirovolakis, Eftichis (31 January 2019). Deleuze and Guattari's Philosophy of Freedom: Freedom's Refrains. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-429-66352-9.

- Tondl, L. (2012). Problems of Semantics: A Contribution to the Analysis of the Language Science. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-94-009-8364-9.

- Dirven, René; Verspoor, Marjolijn (30 June 2004). Cognitive Exploration of Language and Linguistics: Second revised edition. John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-9541-5.

- Palmer, Frank Robert (1976). Semantics: A New Outline. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521209277.

- Noth, Winfried (22 September 1990). Handbook of Semiotics. Indiana University Press. ISBN 978-0-253-20959-7.

- Kearns, Kate (16 September 2011). Semantics. Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-71701-5.

- Blackburn, Simon (1 January 2008). "Truth Conditions". The Oxford Dictionary of Philosophy. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-954143-0.

- Gregory, Howard (2016). Semantics. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415216109.

- Krifka, Manfred (4 September 2001). Wilson, Robert A.; Keil, Frank C. (eds.). The MIT Encyclopedia of the Cognitive Sciences (MITECS). MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-73144-7.

- Pelletier, Francis Jeffry (1994). "The Principle of Semantic Compositionality". Topoi. doi: 10.1007/BF00763644.

- Szabó, Zoltán Gendler (2020). "Compositionality". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 7 February 2024.

- Marti, Genoveva (1998). Sense and Reference. Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Leach, Stephen; Tartaglia, James (11 May 2018). "Postscript: The Blue Flower". The Meaning of Life and the Great Philosophers. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-315-38592-1.

- Abaza, Jack (16 November 2023). The Definitive Answer to the Meaning of Life. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 979-8-3852-0172-3.

- Cunningham, D. J. (2009). "Meaning, Sense, and Reference". In Allan, Keith (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Semantics. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-095969-6.

- Yule, George (2010). The Study of Language (4 ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-76527-5.

- Löbner, Sebastian (2013). Understanding semantics (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-82673-0.

- Edmonds, P. (2009). "Disambiguation". In Allan, Keith (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Semantics. Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-08-095969-6.

- Zalta, Edward N. (2022). "Gottlob Frege". The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Retrieved 9 February 2024.

-

^

- Cunningham 2009, pp. 530–531

- Yule 2010, pp. 113–114

-

^

- Leach & Tartaglia 2018, pp. 274–275

- Abaza 2023, p. 32

- Cunningham 2009, p. 526

- Löbner 2013, pp. 1–2

-

^

- Riemer 2010, pp. 21–22

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 5–6

- Löbner 2013, pp. 1–6, 18–21

- ^ Tondl 2012, p. 111

- ^ Olkowski & Pirovolakis 2019, pp. 65–66

-

^

- Riemer 2010, pp. 21–22

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 5–6

- Löbner 2013, pp. 1–6

- Saeed 2009, pp. 12–13

-

^

- Yule 2010, p. 113

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 5–6

- ^ Zalta 2022, § 1. Frege’s Life and Influences, § 3. Frege’s Philosophy of Language.

-

^

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 7–9

- Cunningham 2009, p. 526

- Saeed 2009, p. 46

-

^

- Cunningham 2009, p. 527

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 7–9

-

^

- Cunningham 2009, p. 526

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 7–9

-

^

- Marti 1998, Lead Section

- Riemer 2010, pp. 27–28

-

^

- Riemer 2010, pp. 25–28

- Griffiths & Cummins 2023, pp. 7–9

- ^ Cunningham 2009, p. 531

- ^ Marti 1998, Lead Section

-

^

- Szabó 2020, Lead Section

- Pelletier 1994, p. 11–12

- Krifka 2001, p. 152

- ^ Löbner 2013, pp. 7–8, 10–12

-

^

- Szabó 2020, Lead Section

- Pelletier 1994, p. 11–12

- Krifka 2001, p. 152

-

^

- Szabó 2020, Lead Section

- Pelletier 1994, p. 11–12

- Krifka 2001, p. 152

-

^

- Gregory 2016, pp. 9–10

- Blackburn 2008, Truth Conditions

- Kearns 2011, pp. 8–10

-

^

- Gregory 2016, pp. 9–10

- Blackburn 2008, Truth Conditions

- Kearns 2011, pp. 8–10

-

^

- Palmer 1976, pp. 25–26

- Noth 1990, pp. 89–90

- Dirven & Verspoor 2004, pp. 28–29

- Riemer 2010, pp. 13–16

-

^

- Palmer 1976, pp. 25–26

- Noth 1990, pp. 89–90

- Dirven & Verspoor 2004, pp. 28–29

- Riemer 2010, pp. 13–16

-

^

- Yule 2010, pp. 115–116

- Saeed 2020, pp. 152–155

- ^ Saeed 2020, p. 63

-

^

- Yule 2010, pp. 116–120

- Saeed 2020, pp. 63–70

-

^

- Edmonds 2009, pp. 223–226

- Murphy & Koskela 2010, p. 57

- ^ Yule 2010, pp. 113–115

-

^

- Saeed 2020, p. 63

- Reif & Polzenhagen 2023, pp. 129–130

-

^

- Riemer 2010, pp. 22–23

- Gamut 1991, pp. 142–143

- Dummett 1981, p. 106

Cite error: There are <ref group=lower-alpha> tags or {{efn}} templates on this page, but the references will not show without a {{reflist|group=lower-alpha}} template or {{notelist}} template (see the

help page).