| Indian Indigenous Religious Traditions | |

| Category: | Folk religious festival |

| Type: | Itinerant dance drama |

| Style: | Ecstatic theatrical |

| Typical Gavari arena | |

| Ethnic group: | Bhil people |

| Region | Mewar in Rajasthan |

| Religion: | Indigenous animistic w/ Hindu influences [1] |

| Duration | 40 days |

| Season: | August, September |

| Troupe size | ±20~80 |

| Troupes/year | ±20-35 |

| Participants | Shamans, players, musicians |

| Characters: | Budia, Rai, Kutkadia, divine avatars, demons, historical characters, sacred animals, authority caricatures [2] |

Gavari (Devanagari: गवरी) is a 40-day ecstatic dance drama tradition dedicated to the Shakti avatar Gavari (aka Gauri), the principal deity of Mewar's Bhil tribe in Rajasthan, India. The Mewari Bhils honor Gavari as the creative protective spirit animating all life; and they perform this ritual annually to invoke, experience and celebrate Her powers. This centuries-old ceremonial cycle employs austere discipline, enraptured trance, and wild theatrics to convey ancient myths, historic events, tribal lore, and satiric political commentary. Among all the world’s folk performance traditions, it is quite unique, especially with respect to its epiphanous energy, scale, duration, ascetic rigour and inspirational messaging as well as its still mysterious provenance and genesis.

Distinctive Characteristics

Divine sanction/participation: Each year bhopa shamans from Mewar's Bhil communities petition the Goddess to permit their village to perform the Gavari ritual and accompany them for the ±5 weeks they would spend on tour. The average wait time for Her consent is about 4~5 years, and once the ritual cycle begins She must also be successfully invoked before each daily ceremony. Only when She visibly possesses one or more troupe members can the dance dramas begin and the ritual proceed.

Scale: Each of the 20~35 different Bhil communities She approves each year immediately forms and dispatches its own Gavari company of 20~80 members. All these troupes then individually crisscross Mewar for the next 5 weeks performing more than 600 day-long village ceremonies in all.

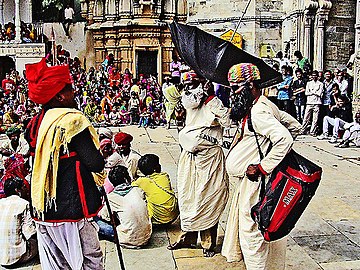

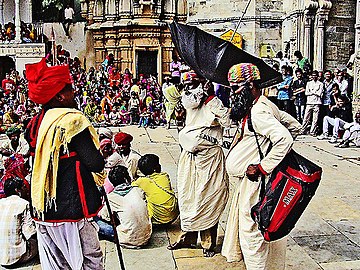

- Gavari turnout

Since village audiences usually number in the many hundreds, all the Gavari

troupes in total can annually play to over a quarter million people.

Duration & Rigour: During the full 40-day Gavari season all players must practice strict austerities to maintain reverent contact with the living earth and Her immanent spirit. [3] They forsake not only sex, alcohol and non-veg foods, but also shoes, beds, bathing, eating greens (which might harm insect life), and survive on a single meal each day until the cycle ends [4].

Messaging: The average Gavari troupe repertoire may include 10~15 classic traditional tales and new ones are still evolving, but the overarching themes are the sacredness of the natural world, radical human equality, and the feminine nature of the divine. These values are reflected in traditional Bhil society where the environment is revered, hierarchy is abhorred, and women enjoy greater rights and status than in communities outside. [5] [6]

Gavari Background

About the Bhils

One of India’s oldest and largest tribes, the Bhil people have primarily lived in the belt extending across contemporary Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh for at least 4,000 years. Though the historic Bhil culture is now characterized as "chivalrous, robust and virile" [7] the rise of Hindu hegemony over the last two millennia relegated Bhils and other indigenous tribes to the very bottom of the social hierarchy, well below Untouchables. The British Raj even worsened their lot in the mid-1800s by designating Bhils a "criminal tribe" for resisting British occupation [8] [9] [10] and massacring them with impunity well into the 20th century. [11]

The Bhil name is said to come from bil, the Dravidian word for bow as they were initially forest dwelling hunter-gatherers and superlative archers. The Mewari Bhils are known to have used their archery skills, forest lore and guerrilla tactics to defend their lands and autonomy up until the 7th century when they forged an.amicable enduring alliance with the Rajput Guhila clan [12] Thanks to this entente, Mewar's Bhils fought many punishing defensive campaigns alongside their Rajput allies, and in return faced few discriminatory indignities and even Bhil/Rajput intermarriage was frequently allowed.. [13] [14] About 10 million Bhils exist in India today, but only the ±7% who reside in Mewar observe or practice the Gavari tradition.

Socially and spiritually, the Bhils have been a matrilineal, Goddess-worshiping people for most of their history, and Bhil women enjoyed the same rights and status as men. Recently. however, patriarchal Hindutva ideology and sanskritization have visibly restricted their freedoms and eroded their standing, especially among those exposed to government education and modern urban culture. [15] [16]

About Mewar

Mewar is a 12-century-old erstwhile “ princely state” in southern Rajasthan that encompassed the modern districts of Udaipur, Chittorgarh, Rajsamand, Bhilwara and Pratapgarh.

Though it voluntarily dissolved into independent India in 1947, Mewar is still renowned as a singularly noble realm where the infra-caste Bhil tribals and ruling caste Rajputs co-existed as brothers and together resisted foreign subjugation for more than ten centuries [17].

The Bhils’ tenure in the region dates back at least 4000 years and the Rajputs since the 7th century. Their cordial alliance and collaborative defense against Turkic legions, Mughal armies and East India Company infiltration helped foster a unique ecumenical spectrum of resistance that embraced all Hindu castes as well as Jains and Muslims. That cooperative history has had enduring consequences. There have been no reported cases of bloody communal conflict in Mewar before or after independence, not even during the murderous cross-country riots that followed the Indo-Pak Partition, Indira Gandhi’s assassination or the demolition.of Babri Masjid.

Lessons in indigenous resistance

In their many initial battles against invaders, Mewar’s Rajput warriors were reputedly valiant and proficient, but not always victorious. They were largely trained in old-school army-to-army collision combat and this courtly strategy rarely fared well against overwhelming odds. Consequently when facing huge well-armed hordes like the Mughal armies, the Rajput forces were often routed and dispersed. [18]

As Rajput allies, the Mewari Bhils would frequently contribute opening arrow fusillades to these head-on confrontations, but then sensibly withdraw to their forest sanctuaries.Their reported reasoning was that massive armies, cavalry charges, artillery, war elephants, etc. might all be fine for invading countries, but to merely defend one's own lands it was far more cost-effective to simply make them ungovernable with relentless sniping, ambushes and sabotage. [19] Thus when Rajput leaders like Maharana Pratap lost big battles and took refuge with the Bhils in the forests, their indigenous hosts not only healed and harbored them, they also taught them guerrilla warfare [20] [17]. Together they went on to render Mewar grimly unmanageable for all unwanted interlopers; and thanks to this history of fierce defiance, egalitarian resistance and sovereign pride, Mewar became known as India's most respected princely state. [21] [22] [23]

- Mewar Bhil-Rajput brotherhood - then and now

-

Bhils & Rajputs shown with equal status on Mewar insignia - 16th century

-

Mewar Bhil leaders with Maharana Mahendra Singh Mewar - 2016

Speculations on Origin

Prominent theories: There are many speculative theories about Gavari's genesis, but its true age and origin are still unknown. However, since it is only practiced in Mewar and features stirring episodes from Mewar's medieval history, some learned Gavari students like Bhanu Bharti infer that it began in rural Mewar near the end of the 16th century and cite the following reasoning.

After Mewaris largely regained control of their lands and lives from the Mughals in 1579 [24] [25], the Rajput court gratefully awarded their mountain-dwelling Bhil brethren both unprecedented heraldic recognition and vast tracts of fertile agricultural land. The latter boon gradually drew most Bhils out of their forest encampments and began their transition to village agriculture. The 16th century hypothesis thus holds that this settling down of a vivid semi-nomadic people birthed a nostalgia for their adventurous itinerant heritage, which eventually spawned Gavari's theatrical pilgrimage ritual. Others assert Gavari began in the 3rd or 4th century in Gujarat [26], and still others that it as old as Bhil culture itself and dates back 4 millennia. However, since no conclusive evidence for any of these theories has yet been uncovered, the mystery and debate remain unresolved . [27] [28] [29]

Gavari Structure

Outline of Full Gavari Cycle

- A Bhil majority village receives divine sanction to perform Gavari (usually once every 4~5 years).

- Within 24 hours the shaman/player troupe is formed, roles assigned and costumes prepared.

- Players begin austerities and hold initial rites in the home village until reliable possession is confirmed.

- They then start a pilgrimage to 25~30 other villages where they've been invited or their married sisters or daughters dwell [29].

- In the final days, each troupe returns to its home village for a last performance and closing ceremonies.

- The cycle ends with an immersion rite to return the Goddess’s fertility to their waters and all night raucous celebrations.

Day by Day Pilgrimage Pattern

- A troupe arrives barefoot in its next host village late at night or early morning and is feted by the villagers.

- About 10:00 AM, troupe shamans collect in the village plaza to invoke the Goddess and ask permission to begin.

- Troupe players dance counterclockwise around the shamans to create a sympathetic energy field.

- The Budia Siva/demon figure circles their dance in the opposite direction to hold in the energy and protect it from misuse.

- The Goddess’ arrival is signaled by one or more shamans going into trance and trembling uncontrollably.

- Players then begin to perform a 4~5 hr series of theatrical playlets 15 min to 2 hrs in duration.

- Before each piece a Sutradhar (program director) describes the next episode in Hindi or Mewari.

[30]

(The Bhils sing and perform in their own Mewari dialect that is largely unintelligible to outsiders.) - Villagers from all castes and creeds join the enthusiastic audience and contribute to the hospitality [31].

- Sensitive villagers may also break into trance at any time and are welcomed and blessed by the shamans.

- The ritual performances conclude about 5:00 PM and troupe members and villagers feast together and socialize.

- The players are rarely paid as such, but are generally thanked with simple gifts of grain and fabric.

- Depending on distance, the troupe sets off for the next village that night or at dawn the next day.

Invocations

- Goddess Gavari invocations

-

Ritual implements for invocation rites

Types of Invocation: Gavari employs two similar but distinct invocation rituals. The first is used to ask the Goddess to permit a village to perform the Gavari cycle. This sanction invocation is held in every Mewari Bhil community at the time of the full moon in the Hindu month of Shravana, which usually falls in August after the monsoon planting season ends.

The second is to confirm Her presence at the start of each day's village ceremonies. Both require incense, flowers. shamanic chants, madal drum & thali cymbal music [32], a Shaivite trishula, and the erotically suggestive kindling of a dhuni fire to attract the Goddess and engage Her energies.

Initial sanction invocations are usually held in a darkened sanctuary attended by a small group of bhopa shamans, village elders and veteran Gavari players. Other villagers gather outside to await Her decision which is delivered by a possessed and trembling bhopa. He proceeds to channel Her spirit as She explains why She will or won't allow them to perform this year. Typical reasons for refusal are said to include discord in the village, shrine disrepair, a poor monsoon, a crop blight, etc., which must be dealt with satisfactorily before petitioning Her again. [33]

Daily confirmation invocations are performed around an ad hoc altar in the center of the Gavari arena where shamans, musicians and senior players gather in a tight circle. The rest of the players and occasionally villagers dance counterclockwise around this core to create a welcoming energy field. A guardian Budia figure circles the dancers in the opposite direction to seal in their energy and protect it from misuse. The Goddess spirit's arrival and presence is signaled by one or more bhopas falling into trembling bhava trance. [34]

Other requisite ritual instruments used after Her manifestation include peacock feather sceptres to dramatize and distribute possession's quivering energetic power, and heavy saankal chains with which trance-elated participants often beat their backs to cool and calm their fervor.

Possession & Trance: Successful invocations have several visible effects. First they connect the village shaman(s) to the Goddess spirit to audibly express Her concerns, requests and will. Second, they infuse the Gavari players with creative inspiration to ably enact their roles. Finally, they can overwhelm sensitive villagers with a sense of wonder, grace and bliss. Entranced villagers may be welcomed into the shaman circle to amplify its energy or approached for healings and blessings by other members of the crowd. Those possessed often later report feelings of great exhilaration and selfless unity with all surrounding life. Such experiences reinforce Bhils' belief in Gavari's power, their own inalienable equality, and the sacredness of the natural world.

- Gavari-induced Possession & Rapture

Archetypal Dramas

Among Gavari’s many tales and mythic dramas, two of the most popular are Badalya Hindawa (The Banyan Swing) and Bhilurana (King of the Bhils).

Badalya Hindawa recounts how the Goddess re-greened the Earth after a life-erasing flood and fiercely defends it thereafter from greed, stupidity and wanton harm. The playlet's final episodes feature a powerful guru who loses his disciples beneath a sacred Banyan and demands that the local king destroy it as an illicit source of power. The unnerved king complies and has the tree cut down. The Goddess and Her devi sisters are outraged at this desecration and slip into his court disguised as acrobatic dancers to exact revenge. They lure the kng close with their artistry, reveal their true nature, indict him for cowardice & sacrilege, and mortally terminate his reign.

Bhilurana is the tale of a composite leader representing five centuries of Bhil resistance to intrusions of all kinds. The play compresses and conflates the armed might of Turkic, Mughal and British invaders and dramatizes how Goddess-backed Bhil warriors finally drove them all away with daring

mano a mano ambushes and shrewd

guerrilla war.

Both dramas end with contagious celebrations, salutations to the Goddess, and clear warnings to other hierarchs and interlopers to never violate Nature or their sovereignty again [35]:

Special Characters

Depending on the day and the plays selected a single Gavari ceremony can present dozens of different characters - goddess avatars, gods, demons, historical figures, sacred animals, corrupt officials, etc. The only constant roles, which exist outside the dramas, are the Budia figure, his twin Rai devi consorts and Kutkadia, the sutradhar or Gavari MC.

Budia embodies a powerful fusion of Shaivite and demonic energies and is a vital protective Gavari figure. He is distinguished by his dramatic horse hair-fringed mask, sacred staff and twin Rai consorts. In each day’s Gavari ceremony the Budia character has three main duties: 1) circling the arena during opening invocations in the opposite direction as the dancers to seal in and protect the energy field they are generating; 2) patrolling the arena perimeter during dance drama sequences to prevent audience members from entering the players' area or shaman circle unless they are clearly entranced; and 3). periodically holding court at the arena’s edge with his Rai escorts to accept diverse offerings on behalf of the troupe and confer blessings on devout supplicants [36]

Every Gavari village has its own iconic Budia mask, which is treated as a sacred object and often handed down for generations.

- The Many Faces of Budia

Contemporary Significance

Arenas of visible influence

In search of more liberating dramatic forms, famed Indian theatrical director Bhanu Bharti studied with Gavari troupes in the 1990s and began to incorporate their techniques and even players into his own creations. "I wanted to study a community still rooted in shared beliefs and communal consciousness which the urban society has long lost...My productions of 'Pashu Gayatri', 'Kaal Katha' and ' Amar Beej' are experiments towards re-discovering that authentic and magical theatrical experience." [37]

Ecological

"Gavari has little to do with Hinduism. It represents a more ancient universal appreciation of Nature, Her needs and Her powers... Modern urban society remains unaware of this wisdom and has been foolishly ignoring it for a very long time." - Dr. Velaram Ghogra, Bhil elder and former ICITP [38] director [39]

Gavari’s messaging and values deem the beauty and power of the natural world to be the ultimate expression of divinity and thus hold its welfare sacrosanct. Willful or heedless damage to its diversity, health or future is thus regarded as not only short-sighted and suicidal, but also criminal and blasphemous [40].Such views are the seed of sustainable “Seven Generation” thinking among many indigenous tribes and their current widespread battles to safeguard water resources, endangered ecosystems and bio-cultural diversity. [41] [42]

Societal

Gavari's itinerant format continues to closely network and promote solidarity among Mewar's scattered rural villages as well as their constituent castes and religious communities. [43] Its rich mythic and historical repertoire also helps keep often demeaned tribal youth aware of their proud ancient heritage. [44]

Financial/Educational

Gavari’s comedic skits on farm finance, greedy middlemen and corrupt merchants offer villagers wry lessons in real world commerce and economic self-defense, especially with regard to crop brokers, money lenders, credit scams, and urban conceptions of “wealth”. [33]

Evolutionary

Gavari plays and praxis emphasize inspired improvisation over rehearsal and rote expertise. The beginnings and ends of Gavari dramas are commonly decided, but how things transpire in between is highly mutable. There are no Gavari scripts and many Bhil players are unlettered farmers and laborers. [45] Individual plays can continue for hours, contain long soliloquies & dialogues, and are only performed every 4 or 5 years, so players greatly depend on divine "inspiration" to guide their delivery and portrayals. They therefore strive to perform in a receptive trance known as bhava, which resembles the fluid creative state that musicians and athletes call "flow" or “ the zone”. This intuitive improvisational approach fosters great creative diversity and different villages present the same stories in many very different ways.

Political Empowerment

Like the Bhils, Gavari is righteously egalitarian and disrespectful of unjust authority. [46] Its dramas vividly depict and celebrate the dispatching of powerful officials, gurus and merchants either by the mocking scorn of villagers or the sword of the Goddess in a protective maternal rage. No authority figure is spared and some playlets happily lampoon kings, foibled Hindu gods like Krishna, and even charlatan Bhopa shamans. [47] [35] The healthy skepticism such skits reflected and encouraged in rural Mewar helped birth India's 2005 Right to Information Act, which has been journalistically hailed as “the most significant change to Indian democracy since Independence” [48]

Gender Re-equalization

Gavari elevates the protective creative feminine spirit to supremacy in its pantheon; and in all its critical dramatic confrontations it is the goddesses, not the gods who prevail. However, since players must embody their characters for the full 40-day cycle, women are not allowed to tour as actors with the troupe. The ritual 4~5-day menstrual isolation Bhil women observe each month would rob the troupe of a vital character for nearly a week. Consequently, all female characters are sensually portrayed by otherwise macho young village men who feel honored to play these roles. [35]

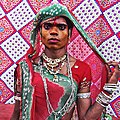

- Young male Bhil villagers proudly play feminine roles

-

Elegant Bhanjara lady

-

Attendant devi to the Goddess

Cultural impact

Gavari not only reiterates and reinforces all the above mentioned values with great theatric élan, it confirms its messaging with the visible presence of divine possession in the Bhopa, players and crowd. It also tightens inter-community bonds with its month of itinerant village visitations and solidifies Bhils’ sense of responsibility for a world far beyond their neighboring fields. [40]. Although only Bhils play roles in the ceremony, Gavari performances also internally solidify communities by involving all castes, communities and age groups in the preparations and audience delight. [49]

The repercussions of this ancient “progressive” ethic have been widespread and lasting. Bhil strongholds like Jaisamand, Jadhol and Dungarpur have been leaders in Rajasthan’s organic farming defense [50], women’s empowerment campaigns and agro-forestry programs for many years. Some campaigns have reverberated nationally. India’s modern anti-corruption movement that birthed the insurgent Aam Admi (Common Folk) Party is actually rooted not in urban activism, but in the Bhil-assisted RTI (Right To Information) & accountability campaigns that first erupted in Mewari villages in the late 1990s. [48]

Overall, the Gavari tradition reflects the Mewari Bhils’ indigenous triad of insubordinate, egalitarian and eco-sensitive values, which both helped preserve Mewar’s environment and autonomy for centuries and may offer timeless grounding for a sane evolutionary agenda today.

Current Status

Just as Gavari's central ecological and egalitarian values are gaining currency and respect internationally, the tradition at home has fallen on hard times [3] Rajasthan's government schools now forbid Bhil student “ truancy” to accompany their village Gavari troupes on their month-long pilgrimages. This alone is potentially lethal since Gavari has no scripts or schools and the only way to learn its ceremonies, arts and stories is as an apprentice participant.Modern Indian society’s ignorance of and contempt for indigenous traditions has also taken its toll, and Bhil students are often ridiculed at school for their outcaste status, “primitive” beliefs, and Gavari “foolishness”. Shame and bullying are so pervasive that many students drop out [51] and an increasing number of families drop their Bhil name altogether and adopt other surnames to disguise their origins. Add to this the accelerating exodus of working age youth to metro centers in search of menial employment and the average size and number of rural Gavari troupes continues decline [31].

- Children of Gavari - Early apprenticeship roles

There are, however, also positive updrafts appearing. The first English language introduction to Gavari is now available [35]; lobbying is underway for Sangeet Nakat Akademi and UNESCO recognition of Gavari as a globally significant Intangible Cultural Heritage treasure; an increasing number of Gavari clips are appearing on Youtube [52] and Japanese scholars have initiated innovative economic studies of Gavari's societal benefits [53]

Domestically Udaipur's West Zone Cultural Centre has started presenting films and samples of Gavari artistry [54]; and local eco-festivals are also introducing the tradition to urban audiences [55]. In 2016 the Udaipur District Collector and Rajasthan Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje mobilized local agencies and NGOs to create “Rediscovering Gavari” [56], a multi-year program to promote "Gavari as an ancient folk art miracle... spiritually arousing, artistically surprising and historically mysterious." [57]

The Rediscovering Gavari program invited 12 rural troupes to perform the ceremony on different days in iconic Udaipur settings. These unprecedented events exposed thousands of tourists and townsfolk to Gavari for the first time and sparked a rare blaze of media attention. [26] [2] This was followed by the first Gavari presentation in Delhi at the 2016 National Tribal Carnival, which was attended by Prime Minister Modi who offered lavish praise and encouragement. [58]

Local Bhil organizations are also becoming more active in promoting Gavari and its core values. The Mewar Adivasi Samiti (Mewar Indigenous Association) which represents most of the region's Bhils and sponsors major Gavari events [59], sent a declaration of support in late 2016 to the Standing Rock Sioux tribe fighting the Dakota Access Pipeline in the US. Their letter states that the Bhils too “face increasing threats to our lands, wellbeing and cultures from huge growth-obsessed corporate entities”, which they see as a literal “cancer” and propose to abolish them globally as an existential threat to planetary health. [60] t [61]

See also

|

|

External links

References

-

^ 1973-, Majhi, Anita Srivastava (2010).

Tribal culture, continuity, and change : a study of Bhils in Rajasthan. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 142.

ISBN

978-8183242981.

OCLC

609982250.

{{ cite book}}:|last=has numeric name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^ a b "Mewar's ecstatic tribal folk opera 'Gavri' seeks global recognition | Udaipur Kiran : Latest News Headlines, Current Live Breaking News from India & World". udaipurkiran.com. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^

a

b

Tribal dances of India. Tribhuwan, Robin D., Tribhuwan, Preeti R. New Delhi: Discovery Pub. House. 1999. p. 106.

ISBN

8171414435.

OCLC

41143548.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: others ( link) - ^ "MASKINDIA BHIL GAVRI GAVARI DANCE Chhoti Undri village Rajasthan : ETHNOFLORENCE Indian and Himalayan folk and tribal arts". ethnoflorence.skynetblogs.be (in French). Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ Mitra, Aparna (2008-06-01). "The status of women among the scheduled tribes in India". The Journal of Socio-Economics. Behavioral Dimensions of the Firm Special Issue. 37 (3): 1202–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2006.12.077.

- ^ "Bhil tribal communities". www.indianmirror.com. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ^ Rajasthan State Gazetteer: History and Culture - Vol 2. Jaipur: Directorate, District Gazetteers, Government of Rajasthan. 1995. p. 205.

- ^ "Scheduled Castes and Tribes - Fault Lines created by British Raj". MyIndMakers. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ^ PUCL. "The Branded Tribes of India". www.pucl.org. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ^ "The Legacy Of Criminal Tribes Act In The Present Context By Goldy M. George". www.countercurrents.org. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ^ "Bhilurana Redux: Brits respond to Bhil resistance with the Mangadh Hill massacre – Mewar Gavari". www.gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

-

^ James, Minahan (August 2016).

Encyclopedia of stateless nations : ethnic and national groups around the world (Second ed.). Santa Barbara, California. p. 76.

ISBN

978-1610699549.

OCLC

953458549.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher ( link) - ^ "Bhil - definition of Bhil | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

-

^ 1941-, Tiwari, S. K. (Shiv Kumar) (2002).

Tribal roots of Hinduism (1st ed.). New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. pp. 270–271.

ISBN

8176252999.

OCLC

51751590.

{{ cite book}}:|last=has numeric name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^ James., Minahan (2012). Ethnic groups of South Asia and the Pacific : an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1598846607. OCLC 819572006.

-

^ Mann, K. (1996).

Tribal women : on the Threshold of Twenty-first Century. New Delhi: M D Publications. pp. 69–72.

ISBN

8185880883.

OCLC

34753364.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year ( link) - ^

a

b 1782-1835., Tod, James (1987).

Annals and antiquities of Rajasthan, or the Central and Western Rajput states of India. Crooke, William, 1848-1923. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

ISBN

8120803809.

OCLC

153814424.

{{ cite book}}:|last=has numeric name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^ "History of Akbar - Mughals History". www.historytuition.com. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- ^ "Quick - Scan of History of Mewar". Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ^ "The Bhils: The Most Famous Hindu Tribal Warriors | Hindu Human Rights Online News Magazine". www.hinduhumanrights.info. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "Udaipur, Mewar - Indian Princely State". www.crwflags.com. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "How post-independence India could have been a monarchy? - Monarchy Forum". royalcello.websitetoolbox.com. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ Susan., Bayly (2001). Caste, society and politics in India from the eighteenth century to the modern age. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0521798426. OCLC 47068695.

-

^ ..., Chandra, Satish, 1922- (2005).

Medieval India : from Sultanat to the Mughals (Revised ed.). New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications. pp. 121–122.

ISBN

8124110662.

OCLC

469652456.

{{ cite book}}:|last=has numeric name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list ( link) - ^ "mughal-mewarconflict - airavat". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- ^ a b "Going global: Mewar's tribal folk opera 'Gavari' ready for international stage - Times of India". The Times of India. 2016-08-29. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ Rajasthan State Gazetteer: History and culture. Directorate, District Gazetteers, Government of Rajasthan. 1995. pp. 199, 205.

-

^

Fairs and festivals of Indian tribes. Tribhuwan, Robin D. New Delhi: Discovery Pub. House. 2003. p. 57.

ISBN

8171416403.

OCLC

50712988.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: others ( link) - ^ a b "Gavari – A Dance Drama of Bhils". UdaipurBlog. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "Gavari- The Incredible Play of Bhils". UdaipurTimes.com. 2011-09-21. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^

a

b 1973-, Majhi, Anita Srivastava (2010).

Tribal culture, continuity, and change : a study of Bhils in Rajasthan. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 150.

ISBN

978-8183242981.

OCLC

609982250.

{{ cite book}}:|last=has numeric name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^ manoharsenal (2010-10-04), RAJASTHANI FOLK MUSICAL INSTRUMENT -MADAL & THALI, retrieved 2017-07-15

- ^ a b "Gavari Introduction – Mewar Gavari". www.gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "'Gavri' the Opera of Mewar". UdaipurTimes.com. 2010-09-28. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ a b c d Agneya, Harish (2014). Gavari - Mewar's electrifying tribal dance-drama: An Illustrated Introduction. India: Tuneer Films. p. 24. ISBN 978-9352123292.

- ^ "The Many Faces of Budia – Mewar Gavari". www.gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- ^ "Review: The Theatre of Bhanu Bharti". 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "ICITP – Indian Confederation of Indigenous & Tribal Peoples". icitp.info. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ Udaipur Shakti Works (2014-05-28), Shakti Sunday May 25: Velaram on Tribal Values & Consciousness, retrieved 2017-07-16

- ^ a b "Mewar Gavari – Mewar's ecstatic tribal folk opera". gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ "11 Indigenous resistance movements you need to know | rabble.ca". rabble.ca. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ^ "Year of Clout: 10 Stories of Indigenous Environmental Influence in 2015 - Indian Country Media Network". indiancountrymedianetwork.com. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

-

^

South Asian folklore : an encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Claus, Peter J., Diamond, Sarah, 1966-, Mills, Margaret Ann. New York: Routledge. 2003. p. 239.

ISBN

0415939194.

OCLC

49276478.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: others ( link) -

^

Tribal dances of India. Tribhuwan, Robin D., Tribhuwan, Preeti R. New Delhi: Discovery Pub. House. 1999. p. 106.

ISBN

8171414435.

OCLC

41143548.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: others ( link) - ^ "Bhils - Dictionary definition of Bhils | Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

-

^ E., Henderson, Carol (2002).

Culture and customs of India. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 156.

ISBN

0313305137.

OCLC

58471382.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) -

^ Chandalia, Hemendra S I N G H.

"Tribal Dance-drama Gavari : Theatre of Subversion and Popular Faith".

{{ cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=( help) - ^

a

b

"The invisible history of peoples movements". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

{{ cite news}}: C1 control character in|title=at position 32 ( help) - ^ "Keeping history alive dramatically". The Hindu. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ "Udaipur's Gati Gaum Becomes Rajasthan's First Internationally Certified Organic Village". UdaipurTimes.com. 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ^ "ADIVASIS, NAXALITES, AND INDIAN DEMOCRACY, Economic and Political Weekly « ::Welcome to Ramachandra Guha.in::". ramachandraguha.in. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "gavari - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ^ "Creative Economy study on Mewar's Gavari tradition by Japanese Researchers | UdaipurTimes.com". UdaipurTimes.com. 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "Aarnya Parva Enthralls Audiences - Event Review @ Creanara". www.creanara.com. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^ "Shakti Sunday resonates with World Music Day & honors Gavari tradition | UdaipurTimes.com". UdaipurTimes.com. 2014-06-23. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "Rediscovering Gavari – 2016 – Mewar Gavari". www.gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "Administration will lay emphasis on Gavari festival. | Daily Udaipur". Daily Udaipur. 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "National tribal festival at new delhi, mewars gavri dance". m.rajasthanpatrika.patrika.com. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "Mewar Adivasi Samiti – Mewar Gavari". www.gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ^ "Indigenous Indian support letters for the anti-DAPL resistance – ICITP". Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ "Climate Change Requires Change of Consciousness". Volatility. 2015-07-27. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

Category:Community building Category:Cultural anthropology Category:Dance culture Category:Folk culture Category:Folk religion Category:Goddesses Category:Indian folk culture Category:Indigenous culture Category:Indigenous peoples and the environment Category:Indigenous peoples Category:Indigenous theatre Category:Nature spirits Category:Pantheism Category:Rajasthani culture Category:Shamanism Category:Shamanistic festivals Category:Shamanic music Category:Tribes of India

| Indian Indigenous Religious Traditions | |

| Category: | Folk religious festival |

| Type: | Itinerant dance drama |

| Style: | Ecstatic theatrical |

| Typical Gavari arena | |

| Ethnic group: | Bhil people |

| Region | Mewar in Rajasthan |

| Religion: | Indigenous animistic w/ Hindu influences [1] |

| Duration | 40 days |

| Season: | August, September |

| Troupe size | ±20~80 |

| Troupes/year | ±20-35 |

| Participants | Shamans, players, musicians |

| Characters: | Budia, Rai, Kutkadia, divine avatars, demons, historical characters, sacred animals, authority caricatures [2] |

Gavari (Devanagari: गवरी) is a 40-day ecstatic dance drama tradition dedicated to the Shakti avatar Gavari (aka Gauri), the principal deity of Mewar's Bhil tribe in Rajasthan, India. The Mewari Bhils honor Gavari as the creative protective spirit animating all life; and they perform this ritual annually to invoke, experience and celebrate Her powers. This centuries-old ceremonial cycle employs austere discipline, enraptured trance, and wild theatrics to convey ancient myths, historic events, tribal lore, and satiric political commentary. Among all the world’s folk performance traditions, it is quite unique, especially with respect to its epiphanous energy, scale, duration, ascetic rigour and inspirational messaging as well as its still mysterious provenance and genesis.

Distinctive Characteristics

Divine sanction/participation: Each year bhopa shamans from Mewar's Bhil communities petition the Goddess to permit their village to perform the Gavari ritual and accompany them for the ±5 weeks they would spend on tour. The average wait time for Her consent is about 4~5 years, and once the ritual cycle begins She must also be successfully invoked before each daily ceremony. Only when She visibly possesses one or more troupe members can the dance dramas begin and the ritual proceed.

Scale: Each of the 20~35 different Bhil communities She approves each year immediately forms and dispatches its own Gavari company of 20~80 members. All these troupes then individually crisscross Mewar for the next 5 weeks performing more than 600 day-long village ceremonies in all.

- Gavari turnout

Since village audiences usually number in the many hundreds, all the Gavari

troupes in total can annually play to over a quarter million people.

Duration & Rigour: During the full 40-day Gavari season all players must practice strict austerities to maintain reverent contact with the living earth and Her immanent spirit. [3] They forsake not only sex, alcohol and non-veg foods, but also shoes, beds, bathing, eating greens (which might harm insect life), and survive on a single meal each day until the cycle ends [4].

Messaging: The average Gavari troupe repertoire may include 10~15 classic traditional tales and new ones are still evolving, but the overarching themes are the sacredness of the natural world, radical human equality, and the feminine nature of the divine. These values are reflected in traditional Bhil society where the environment is revered, hierarchy is abhorred, and women enjoy greater rights and status than in communities outside. [5] [6]

Gavari Background

About the Bhils

One of India’s oldest and largest tribes, the Bhil people have primarily lived in the belt extending across contemporary Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Madhya Pradesh for at least 4,000 years. Though the historic Bhil culture is now characterized as "chivalrous, robust and virile" [7] the rise of Hindu hegemony over the last two millennia relegated Bhils and other indigenous tribes to the very bottom of the social hierarchy, well below Untouchables. The British Raj even worsened their lot in the mid-1800s by designating Bhils a "criminal tribe" for resisting British occupation [8] [9] [10] and massacring them with impunity well into the 20th century. [11]

The Bhil name is said to come from bil, the Dravidian word for bow as they were initially forest dwelling hunter-gatherers and superlative archers. The Mewari Bhils are known to have used their archery skills, forest lore and guerrilla tactics to defend their lands and autonomy up until the 7th century when they forged an.amicable enduring alliance with the Rajput Guhila clan [12] Thanks to this entente, Mewar's Bhils fought many punishing defensive campaigns alongside their Rajput allies, and in return faced few discriminatory indignities and even Bhil/Rajput intermarriage was frequently allowed.. [13] [14] About 10 million Bhils exist in India today, but only the ±7% who reside in Mewar observe or practice the Gavari tradition.

Socially and spiritually, the Bhils have been a matrilineal, Goddess-worshiping people for most of their history, and Bhil women enjoyed the same rights and status as men. Recently. however, patriarchal Hindutva ideology and sanskritization have visibly restricted their freedoms and eroded their standing, especially among those exposed to government education and modern urban culture. [15] [16]

About Mewar

Mewar is a 12-century-old erstwhile “ princely state” in southern Rajasthan that encompassed the modern districts of Udaipur, Chittorgarh, Rajsamand, Bhilwara and Pratapgarh.

Though it voluntarily dissolved into independent India in 1947, Mewar is still renowned as a singularly noble realm where the infra-caste Bhil tribals and ruling caste Rajputs co-existed as brothers and together resisted foreign subjugation for more than ten centuries [17].

The Bhils’ tenure in the region dates back at least 4000 years and the Rajputs since the 7th century. Their cordial alliance and collaborative defense against Turkic legions, Mughal armies and East India Company infiltration helped foster a unique ecumenical spectrum of resistance that embraced all Hindu castes as well as Jains and Muslims. That cooperative history has had enduring consequences. There have been no reported cases of bloody communal conflict in Mewar before or after independence, not even during the murderous cross-country riots that followed the Indo-Pak Partition, Indira Gandhi’s assassination or the demolition.of Babri Masjid.

Lessons in indigenous resistance

In their many initial battles against invaders, Mewar’s Rajput warriors were reputedly valiant and proficient, but not always victorious. They were largely trained in old-school army-to-army collision combat and this courtly strategy rarely fared well against overwhelming odds. Consequently when facing huge well-armed hordes like the Mughal armies, the Rajput forces were often routed and dispersed. [18]

As Rajput allies, the Mewari Bhils would frequently contribute opening arrow fusillades to these head-on confrontations, but then sensibly withdraw to their forest sanctuaries.Their reported reasoning was that massive armies, cavalry charges, artillery, war elephants, etc. might all be fine for invading countries, but to merely defend one's own lands it was far more cost-effective to simply make them ungovernable with relentless sniping, ambushes and sabotage. [19] Thus when Rajput leaders like Maharana Pratap lost big battles and took refuge with the Bhils in the forests, their indigenous hosts not only healed and harbored them, they also taught them guerrilla warfare [20] [17]. Together they went on to render Mewar grimly unmanageable for all unwanted interlopers; and thanks to this history of fierce defiance, egalitarian resistance and sovereign pride, Mewar became known as India's most respected princely state. [21] [22] [23]

- Mewar Bhil-Rajput brotherhood - then and now

-

Bhils & Rajputs shown with equal status on Mewar insignia - 16th century

-

Mewar Bhil leaders with Maharana Mahendra Singh Mewar - 2016

Speculations on Origin

Prominent theories: There are many speculative theories about Gavari's genesis, but its true age and origin are still unknown. However, since it is only practiced in Mewar and features stirring episodes from Mewar's medieval history, some learned Gavari students like Bhanu Bharti infer that it began in rural Mewar near the end of the 16th century and cite the following reasoning.

After Mewaris largely regained control of their lands and lives from the Mughals in 1579 [24] [25], the Rajput court gratefully awarded their mountain-dwelling Bhil brethren both unprecedented heraldic recognition and vast tracts of fertile agricultural land. The latter boon gradually drew most Bhils out of their forest encampments and began their transition to village agriculture. The 16th century hypothesis thus holds that this settling down of a vivid semi-nomadic people birthed a nostalgia for their adventurous itinerant heritage, which eventually spawned Gavari's theatrical pilgrimage ritual. Others assert Gavari began in the 3rd or 4th century in Gujarat [26], and still others that it as old as Bhil culture itself and dates back 4 millennia. However, since no conclusive evidence for any of these theories has yet been uncovered, the mystery and debate remain unresolved . [27] [28] [29]

Gavari Structure

Outline of Full Gavari Cycle

- A Bhil majority village receives divine sanction to perform Gavari (usually once every 4~5 years).

- Within 24 hours the shaman/player troupe is formed, roles assigned and costumes prepared.

- Players begin austerities and hold initial rites in the home village until reliable possession is confirmed.

- They then start a pilgrimage to 25~30 other villages where they've been invited or their married sisters or daughters dwell [29].

- In the final days, each troupe returns to its home village for a last performance and closing ceremonies.

- The cycle ends with an immersion rite to return the Goddess’s fertility to their waters and all night raucous celebrations.

Day by Day Pilgrimage Pattern

- A troupe arrives barefoot in its next host village late at night or early morning and is feted by the villagers.

- About 10:00 AM, troupe shamans collect in the village plaza to invoke the Goddess and ask permission to begin.

- Troupe players dance counterclockwise around the shamans to create a sympathetic energy field.

- The Budia Siva/demon figure circles their dance in the opposite direction to hold in the energy and protect it from misuse.

- The Goddess’ arrival is signaled by one or more shamans going into trance and trembling uncontrollably.

- Players then begin to perform a 4~5 hr series of theatrical playlets 15 min to 2 hrs in duration.

- Before each piece a Sutradhar (program director) describes the next episode in Hindi or Mewari.

[30]

(The Bhils sing and perform in their own Mewari dialect that is largely unintelligible to outsiders.) - Villagers from all castes and creeds join the enthusiastic audience and contribute to the hospitality [31].

- Sensitive villagers may also break into trance at any time and are welcomed and blessed by the shamans.

- The ritual performances conclude about 5:00 PM and troupe members and villagers feast together and socialize.

- The players are rarely paid as such, but are generally thanked with simple gifts of grain and fabric.

- Depending on distance, the troupe sets off for the next village that night or at dawn the next day.

Invocations

- Goddess Gavari invocations

-

Ritual implements for invocation rites

Types of Invocation: Gavari employs two similar but distinct invocation rituals. The first is used to ask the Goddess to permit a village to perform the Gavari cycle. This sanction invocation is held in every Mewari Bhil community at the time of the full moon in the Hindu month of Shravana, which usually falls in August after the monsoon planting season ends.

The second is to confirm Her presence at the start of each day's village ceremonies. Both require incense, flowers. shamanic chants, madal drum & thali cymbal music [32], a Shaivite trishula, and the erotically suggestive kindling of a dhuni fire to attract the Goddess and engage Her energies.

Initial sanction invocations are usually held in a darkened sanctuary attended by a small group of bhopa shamans, village elders and veteran Gavari players. Other villagers gather outside to await Her decision which is delivered by a possessed and trembling bhopa. He proceeds to channel Her spirit as She explains why She will or won't allow them to perform this year. Typical reasons for refusal are said to include discord in the village, shrine disrepair, a poor monsoon, a crop blight, etc., which must be dealt with satisfactorily before petitioning Her again. [33]

Daily confirmation invocations are performed around an ad hoc altar in the center of the Gavari arena where shamans, musicians and senior players gather in a tight circle. The rest of the players and occasionally villagers dance counterclockwise around this core to create a welcoming energy field. A guardian Budia figure circles the dancers in the opposite direction to seal in their energy and protect it from misuse. The Goddess spirit's arrival and presence is signaled by one or more bhopas falling into trembling bhava trance. [34]

Other requisite ritual instruments used after Her manifestation include peacock feather sceptres to dramatize and distribute possession's quivering energetic power, and heavy saankal chains with which trance-elated participants often beat their backs to cool and calm their fervor.

Possession & Trance: Successful invocations have several visible effects. First they connect the village shaman(s) to the Goddess spirit to audibly express Her concerns, requests and will. Second, they infuse the Gavari players with creative inspiration to ably enact their roles. Finally, they can overwhelm sensitive villagers with a sense of wonder, grace and bliss. Entranced villagers may be welcomed into the shaman circle to amplify its energy or approached for healings and blessings by other members of the crowd. Those possessed often later report feelings of great exhilaration and selfless unity with all surrounding life. Such experiences reinforce Bhils' belief in Gavari's power, their own inalienable equality, and the sacredness of the natural world.

- Gavari-induced Possession & Rapture

Archetypal Dramas

Among Gavari’s many tales and mythic dramas, two of the most popular are Badalya Hindawa (The Banyan Swing) and Bhilurana (King of the Bhils).

Badalya Hindawa recounts how the Goddess re-greened the Earth after a life-erasing flood and fiercely defends it thereafter from greed, stupidity and wanton harm. The playlet's final episodes feature a powerful guru who loses his disciples beneath a sacred Banyan and demands that the local king destroy it as an illicit source of power. The unnerved king complies and has the tree cut down. The Goddess and Her devi sisters are outraged at this desecration and slip into his court disguised as acrobatic dancers to exact revenge. They lure the kng close with their artistry, reveal their true nature, indict him for cowardice & sacrilege, and mortally terminate his reign.

Bhilurana is the tale of a composite leader representing five centuries of Bhil resistance to intrusions of all kinds. The play compresses and conflates the armed might of Turkic, Mughal and British invaders and dramatizes how Goddess-backed Bhil warriors finally drove them all away with daring

mano a mano ambushes and shrewd

guerrilla war.

Both dramas end with contagious celebrations, salutations to the Goddess, and clear warnings to other hierarchs and interlopers to never violate Nature or their sovereignty again [35]:

Special Characters

Depending on the day and the plays selected a single Gavari ceremony can present dozens of different characters - goddess avatars, gods, demons, historical figures, sacred animals, corrupt officials, etc. The only constant roles, which exist outside the dramas, are the Budia figure, his twin Rai devi consorts and Kutkadia, the sutradhar or Gavari MC.

Budia embodies a powerful fusion of Shaivite and demonic energies and is a vital protective Gavari figure. He is distinguished by his dramatic horse hair-fringed mask, sacred staff and twin Rai consorts. In each day’s Gavari ceremony the Budia character has three main duties: 1) circling the arena during opening invocations in the opposite direction as the dancers to seal in and protect the energy field they are generating; 2) patrolling the arena perimeter during dance drama sequences to prevent audience members from entering the players' area or shaman circle unless they are clearly entranced; and 3). periodically holding court at the arena’s edge with his Rai escorts to accept diverse offerings on behalf of the troupe and confer blessings on devout supplicants [36]

Every Gavari village has its own iconic Budia mask, which is treated as a sacred object and often handed down for generations.

- The Many Faces of Budia

Contemporary Significance

Arenas of visible influence

In search of more liberating dramatic forms, famed Indian theatrical director Bhanu Bharti studied with Gavari troupes in the 1990s and began to incorporate their techniques and even players into his own creations. "I wanted to study a community still rooted in shared beliefs and communal consciousness which the urban society has long lost...My productions of 'Pashu Gayatri', 'Kaal Katha' and ' Amar Beej' are experiments towards re-discovering that authentic and magical theatrical experience." [37]

Ecological

"Gavari has little to do with Hinduism. It represents a more ancient universal appreciation of Nature, Her needs and Her powers... Modern urban society remains unaware of this wisdom and has been foolishly ignoring it for a very long time." - Dr. Velaram Ghogra, Bhil elder and former ICITP [38] director [39]

Gavari’s messaging and values deem the beauty and power of the natural world to be the ultimate expression of divinity and thus hold its welfare sacrosanct. Willful or heedless damage to its diversity, health or future is thus regarded as not only short-sighted and suicidal, but also criminal and blasphemous [40].Such views are the seed of sustainable “Seven Generation” thinking among many indigenous tribes and their current widespread battles to safeguard water resources, endangered ecosystems and bio-cultural diversity. [41] [42]

Societal

Gavari's itinerant format continues to closely network and promote solidarity among Mewar's scattered rural villages as well as their constituent castes and religious communities. [43] Its rich mythic and historical repertoire also helps keep often demeaned tribal youth aware of their proud ancient heritage. [44]

Financial/Educational

Gavari’s comedic skits on farm finance, greedy middlemen and corrupt merchants offer villagers wry lessons in real world commerce and economic self-defense, especially with regard to crop brokers, money lenders, credit scams, and urban conceptions of “wealth”. [33]

Evolutionary

Gavari plays and praxis emphasize inspired improvisation over rehearsal and rote expertise. The beginnings and ends of Gavari dramas are commonly decided, but how things transpire in between is highly mutable. There are no Gavari scripts and many Bhil players are unlettered farmers and laborers. [45] Individual plays can continue for hours, contain long soliloquies & dialogues, and are only performed every 4 or 5 years, so players greatly depend on divine "inspiration" to guide their delivery and portrayals. They therefore strive to perform in a receptive trance known as bhava, which resembles the fluid creative state that musicians and athletes call "flow" or “ the zone”. This intuitive improvisational approach fosters great creative diversity and different villages present the same stories in many very different ways.

Political Empowerment

Like the Bhils, Gavari is righteously egalitarian and disrespectful of unjust authority. [46] Its dramas vividly depict and celebrate the dispatching of powerful officials, gurus and merchants either by the mocking scorn of villagers or the sword of the Goddess in a protective maternal rage. No authority figure is spared and some playlets happily lampoon kings, foibled Hindu gods like Krishna, and even charlatan Bhopa shamans. [47] [35] The healthy skepticism such skits reflected and encouraged in rural Mewar helped birth India's 2005 Right to Information Act, which has been journalistically hailed as “the most significant change to Indian democracy since Independence” [48]

Gender Re-equalization

Gavari elevates the protective creative feminine spirit to supremacy in its pantheon; and in all its critical dramatic confrontations it is the goddesses, not the gods who prevail. However, since players must embody their characters for the full 40-day cycle, women are not allowed to tour as actors with the troupe. The ritual 4~5-day menstrual isolation Bhil women observe each month would rob the troupe of a vital character for nearly a week. Consequently, all female characters are sensually portrayed by otherwise macho young village men who feel honored to play these roles. [35]

- Young male Bhil villagers proudly play feminine roles

-

Elegant Bhanjara lady

-

Attendant devi to the Goddess

Cultural impact

Gavari not only reiterates and reinforces all the above mentioned values with great theatric élan, it confirms its messaging with the visible presence of divine possession in the Bhopa, players and crowd. It also tightens inter-community bonds with its month of itinerant village visitations and solidifies Bhils’ sense of responsibility for a world far beyond their neighboring fields. [40]. Although only Bhils play roles in the ceremony, Gavari performances also internally solidify communities by involving all castes, communities and age groups in the preparations and audience delight. [49]

The repercussions of this ancient “progressive” ethic have been widespread and lasting. Bhil strongholds like Jaisamand, Jadhol and Dungarpur have been leaders in Rajasthan’s organic farming defense [50], women’s empowerment campaigns and agro-forestry programs for many years. Some campaigns have reverberated nationally. India’s modern anti-corruption movement that birthed the insurgent Aam Admi (Common Folk) Party is actually rooted not in urban activism, but in the Bhil-assisted RTI (Right To Information) & accountability campaigns that first erupted in Mewari villages in the late 1990s. [48]

Overall, the Gavari tradition reflects the Mewari Bhils’ indigenous triad of insubordinate, egalitarian and eco-sensitive values, which both helped preserve Mewar’s environment and autonomy for centuries and may offer timeless grounding for a sane evolutionary agenda today.

Current Status

Just as Gavari's central ecological and egalitarian values are gaining currency and respect internationally, the tradition at home has fallen on hard times [3] Rajasthan's government schools now forbid Bhil student “ truancy” to accompany their village Gavari troupes on their month-long pilgrimages. This alone is potentially lethal since Gavari has no scripts or schools and the only way to learn its ceremonies, arts and stories is as an apprentice participant.Modern Indian society’s ignorance of and contempt for indigenous traditions has also taken its toll, and Bhil students are often ridiculed at school for their outcaste status, “primitive” beliefs, and Gavari “foolishness”. Shame and bullying are so pervasive that many students drop out [51] and an increasing number of families drop their Bhil name altogether and adopt other surnames to disguise their origins. Add to this the accelerating exodus of working age youth to metro centers in search of menial employment and the average size and number of rural Gavari troupes continues decline [31].

- Children of Gavari - Early apprenticeship roles

There are, however, also positive updrafts appearing. The first English language introduction to Gavari is now available [35]; lobbying is underway for Sangeet Nakat Akademi and UNESCO recognition of Gavari as a globally significant Intangible Cultural Heritage treasure; an increasing number of Gavari clips are appearing on Youtube [52] and Japanese scholars have initiated innovative economic studies of Gavari's societal benefits [53]

Domestically Udaipur's West Zone Cultural Centre has started presenting films and samples of Gavari artistry [54]; and local eco-festivals are also introducing the tradition to urban audiences [55]. In 2016 the Udaipur District Collector and Rajasthan Chief Minister Vasundhara Raje mobilized local agencies and NGOs to create “Rediscovering Gavari” [56], a multi-year program to promote "Gavari as an ancient folk art miracle... spiritually arousing, artistically surprising and historically mysterious." [57]

The Rediscovering Gavari program invited 12 rural troupes to perform the ceremony on different days in iconic Udaipur settings. These unprecedented events exposed thousands of tourists and townsfolk to Gavari for the first time and sparked a rare blaze of media attention. [26] [2] This was followed by the first Gavari presentation in Delhi at the 2016 National Tribal Carnival, which was attended by Prime Minister Modi who offered lavish praise and encouragement. [58]

Local Bhil organizations are also becoming more active in promoting Gavari and its core values. The Mewar Adivasi Samiti (Mewar Indigenous Association) which represents most of the region's Bhils and sponsors major Gavari events [59], sent a declaration of support in late 2016 to the Standing Rock Sioux tribe fighting the Dakota Access Pipeline in the US. Their letter states that the Bhils too “face increasing threats to our lands, wellbeing and cultures from huge growth-obsessed corporate entities”, which they see as a literal “cancer” and propose to abolish them globally as an existential threat to planetary health. [60] t [61]

See also

|

|

External links

References

-

^ 1973-, Majhi, Anita Srivastava (2010).

Tribal culture, continuity, and change : a study of Bhils in Rajasthan. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 142.

ISBN

978-8183242981.

OCLC

609982250.

{{ cite book}}:|last=has numeric name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^ a b "Mewar's ecstatic tribal folk opera 'Gavri' seeks global recognition | Udaipur Kiran : Latest News Headlines, Current Live Breaking News from India & World". udaipurkiran.com. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^

a

b

Tribal dances of India. Tribhuwan, Robin D., Tribhuwan, Preeti R. New Delhi: Discovery Pub. House. 1999. p. 106.

ISBN

8171414435.

OCLC

41143548.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: others ( link) - ^ "MASKINDIA BHIL GAVRI GAVARI DANCE Chhoti Undri village Rajasthan : ETHNOFLORENCE Indian and Himalayan folk and tribal arts". ethnoflorence.skynetblogs.be (in French). Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ Mitra, Aparna (2008-06-01). "The status of women among the scheduled tribes in India". The Journal of Socio-Economics. Behavioral Dimensions of the Firm Special Issue. 37 (3): 1202–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.socec.2006.12.077.

- ^ "Bhil tribal communities". www.indianmirror.com. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ^ Rajasthan State Gazetteer: History and Culture - Vol 2. Jaipur: Directorate, District Gazetteers, Government of Rajasthan. 1995. p. 205.

- ^ "Scheduled Castes and Tribes - Fault Lines created by British Raj". MyIndMakers. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ^ PUCL. "The Branded Tribes of India". www.pucl.org. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ^ "The Legacy Of Criminal Tribes Act In The Present Context By Goldy M. George". www.countercurrents.org. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- ^ "Bhilurana Redux: Brits respond to Bhil resistance with the Mangadh Hill massacre – Mewar Gavari". www.gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

-

^ James, Minahan (August 2016).

Encyclopedia of stateless nations : ethnic and national groups around the world (Second ed.). Santa Barbara, California. p. 76.

ISBN

978-1610699549.

OCLC

953458549.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher ( link) - ^ "Bhil - definition of Bhil | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

-

^ 1941-, Tiwari, S. K. (Shiv Kumar) (2002).

Tribal roots of Hinduism (1st ed.). New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. pp. 270–271.

ISBN

8176252999.

OCLC

51751590.

{{ cite book}}:|last=has numeric name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^ James., Minahan (2012). Ethnic groups of South Asia and the Pacific : an encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, Calif.: ABC-CLIO. pp. 36–37. ISBN 978-1598846607. OCLC 819572006.

-

^ Mann, K. (1996).

Tribal women : on the Threshold of Twenty-first Century. New Delhi: M D Publications. pp. 69–72.

ISBN

8185880883.

OCLC

34753364.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year ( link) - ^

a

b 1782-1835., Tod, James (1987).

Annals and antiquities of Rajasthan, or the Central and Western Rajput states of India. Crooke, William, 1848-1923. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass.

ISBN

8120803809.

OCLC

153814424.

{{ cite book}}:|last=has numeric name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^ "History of Akbar - Mughals History". www.historytuition.com. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- ^ "Quick - Scan of History of Mewar". Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ^ "The Bhils: The Most Famous Hindu Tribal Warriors | Hindu Human Rights Online News Magazine". www.hinduhumanrights.info. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "Udaipur, Mewar - Indian Princely State". www.crwflags.com. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "How post-independence India could have been a monarchy? - Monarchy Forum". royalcello.websitetoolbox.com. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ Susan., Bayly (2001). Caste, society and politics in India from the eighteenth century to the modern age. New York: Cambridge University Press. p. 59. ISBN 0521798426. OCLC 47068695.

-

^ ..., Chandra, Satish, 1922- (2005).

Medieval India : from Sultanat to the Mughals (Revised ed.). New Delhi: Har-Anand Publications. pp. 121–122.

ISBN

8124110662.

OCLC

469652456.

{{ cite book}}:|last=has numeric name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list ( link) - ^ "mughal-mewarconflict - airavat". sites.google.com. Retrieved 2017-07-25.

- ^ a b "Going global: Mewar's tribal folk opera 'Gavari' ready for international stage - Times of India". The Times of India. 2016-08-29. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ Rajasthan State Gazetteer: History and culture. Directorate, District Gazetteers, Government of Rajasthan. 1995. pp. 199, 205.

-

^

Fairs and festivals of Indian tribes. Tribhuwan, Robin D. New Delhi: Discovery Pub. House. 2003. p. 57.

ISBN

8171416403.

OCLC

50712988.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: others ( link) - ^ a b "Gavari – A Dance Drama of Bhils". UdaipurBlog. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "Gavari- The Incredible Play of Bhils". UdaipurTimes.com. 2011-09-21. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^

a

b 1973-, Majhi, Anita Srivastava (2010).

Tribal culture, continuity, and change : a study of Bhils in Rajasthan. New Delhi: Mittal Publications. p. 150.

ISBN

978-8183242981.

OCLC

609982250.

{{ cite book}}:|last=has numeric name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - ^ manoharsenal (2010-10-04), RAJASTHANI FOLK MUSICAL INSTRUMENT -MADAL & THALI, retrieved 2017-07-15

- ^ a b "Gavari Introduction – Mewar Gavari". www.gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "'Gavri' the Opera of Mewar". UdaipurTimes.com. 2010-09-28. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ a b c d Agneya, Harish (2014). Gavari - Mewar's electrifying tribal dance-drama: An Illustrated Introduction. India: Tuneer Films. p. 24. ISBN 978-9352123292.

- ^ "The Many Faces of Budia – Mewar Gavari". www.gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-21.

- ^ "Review: The Theatre of Bhanu Bharti". 2013-09-11. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "ICITP – Indian Confederation of Indigenous & Tribal Peoples". icitp.info. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ Udaipur Shakti Works (2014-05-28), Shakti Sunday May 25: Velaram on Tribal Values & Consciousness, retrieved 2017-07-16

- ^ a b "Mewar Gavari – Mewar's ecstatic tribal folk opera". gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ "11 Indigenous resistance movements you need to know | rabble.ca". rabble.ca. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

- ^ "Year of Clout: 10 Stories of Indigenous Environmental Influence in 2015 - Indian Country Media Network". indiancountrymedianetwork.com. Retrieved 2017-07-26.

-

^

South Asian folklore : an encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka. Claus, Peter J., Diamond, Sarah, 1966-, Mills, Margaret Ann. New York: Routledge. 2003. p. 239.

ISBN

0415939194.

OCLC

49276478.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: others ( link) -

^

Tribal dances of India. Tribhuwan, Robin D., Tribhuwan, Preeti R. New Delhi: Discovery Pub. House. 1999. p. 106.

ISBN

8171414435.

OCLC

41143548.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: others ( link) - ^ "Bhils - Dictionary definition of Bhils | Encyclopedia.com: FREE online dictionary". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

-

^ E., Henderson, Carol (2002).

Culture and customs of India. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press. p. 156.

ISBN

0313305137.

OCLC

58471382.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) -

^ Chandalia, Hemendra S I N G H.

"Tribal Dance-drama Gavari : Theatre of Subversion and Popular Faith".

{{ cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=( help) - ^

a

b

"The invisible history of peoples movements". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

{{ cite news}}: C1 control character in|title=at position 32 ( help) - ^ "Keeping history alive dramatically". The Hindu. Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ "Udaipur's Gati Gaum Becomes Rajasthan's First Internationally Certified Organic Village". UdaipurTimes.com. 2017-05-10. Retrieved 2017-07-20.

- ^ "ADIVASIS, NAXALITES, AND INDIAN DEMOCRACY, Economic and Political Weekly « ::Welcome to Ramachandra Guha.in::". ramachandraguha.in. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "gavari - YouTube". www.youtube.com. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ^ "Creative Economy study on Mewar's Gavari tradition by Japanese Researchers | UdaipurTimes.com". UdaipurTimes.com. 2016-09-19. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "Aarnya Parva Enthralls Audiences - Event Review @ Creanara". www.creanara.com. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

- ^ "Shakti Sunday resonates with World Music Day & honors Gavari tradition | UdaipurTimes.com". UdaipurTimes.com. 2014-06-23. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "Rediscovering Gavari – 2016 – Mewar Gavari". www.gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-16.

- ^ "Administration will lay emphasis on Gavari festival. | Daily Udaipur". Daily Udaipur. 2016-08-04. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "National tribal festival at new delhi, mewars gavri dance". m.rajasthanpatrika.patrika.com. Retrieved 2017-07-17.

- ^ "Mewar Adivasi Samiti – Mewar Gavari". www.gavari.info. Retrieved 2017-07-19.

- ^ "Indigenous Indian support letters for the anti-DAPL resistance – ICITP". Retrieved 2017-07-14.

- ^ "Climate Change Requires Change of Consciousness". Volatility. 2015-07-27. Retrieved 2017-07-18.

Category:Community building Category:Cultural anthropology Category:Dance culture Category:Folk culture Category:Folk religion Category:Goddesses Category:Indian folk culture Category:Indigenous culture Category:Indigenous peoples and the environment Category:Indigenous peoples Category:Indigenous theatre Category:Nature spirits Category:Pantheism Category:Rajasthani culture Category:Shamanism Category:Shamanistic festivals Category:Shamanic music Category:Tribes of India