In political science, Duverger's law(s) ( /ˈduvərʒeɪ/ DOO-vər-zhay) describe the kinds of electoral systems that tend to produce two-party systems or competitive elections with voter choice. [1] [2] [3] In its original form, Maurice Duverger argued that first-preference plurality voting in single-member districts would encourage countries to develop a two-party system, while proportional representation would not. [4] This strong form of Duverger's law has since been qualified by political scientists, [5] [6] who have shown that single-member plurality can produce multi-party systems in many situations, [7] [8] while .

Mechanisms

Maurice Duverger identified two reasons why single-member plurality tends to reduce the effective number of candidates in each electoral district: [9] [10] [11] [3]

- Small parties are unable to win seats in a winner-take-all system, which also reduces the incentive to create a new party (the mechanical factor).

- Voters would rather support one of the stronger parties (the strategic factor, which Duverger originally called "psychological").

The first law corresponds to the effect of winner-take-all or most systems (including single-member districts), while the second corresponds to the use of voting systems subject to favorite betrayal.

Mechanical (underrepresentation) effect

Duverger's first observation is that winner-take-all voting produces a mechanical effect where there are fewer parties in , simply because it is more difficult for a small party to win a seat. The smallest number of votes sufficient to win a

The mechanical effect involves single-member districts that inherently produce disproportional outcomes, with . In each individual seat, because it is only possible for a single party to win. As a result, it is possible for only a . This effect can be diminished by increasing the number of districts, a . The results in a cube root law for countries that use single-member districts, which tends to balance the misrepresentation caused by large districts with the

William H. Riker, citing Douglas W. Rae, noted that strong regional parties can lead to more than two parties receiving seats in the national legislature, even if there are only two parties competitive in any single district. [12] [13] In systems outside the United States, like Canada, [12] United Kingdom and India, multiparty parliaments exist due to the growth of minor parties finding strongholds in specific regions, potentially lessening the psychological fear of a wasted vote by voting for a minor party for a legislative seat. [14] Riker credits Canada's highly decentralized system of government as encouraging minor parties to build support by winning seats locally, which then sets the parties up to get representatives in the House of Commons of Canada. [12]

For legislatures where each seat represents a geographical area and the candidate with the most votes wins that seat, minor parties spread fairly evenly across many districts win less representation than geographically concentrated ones with the same overall level of public support. An example of this is the Liberal Democrats in the United Kingdom, whose proportion of seats in the legislature is consistently far below their proportion of the national vote. The Green Party of Canada is another example; the party received about 5% of the popular vote from 2004 to 2011 but had only won one seat (out of 308) in the House of Commons in the same span of time. Another example was seen in the 1992 U.S. presidential election, when Ross Perot's candidacy received zero electoral votes despite receiving 19% of the popular vote. Gerrymandering is sometimes used to try to collect a population of like-minded voters within a geographically cohesive district so that their votes are not "wasted", but tends to require that minor parties have both a geographic concentration and a redistricting process that seeks to represent them. These disadvantages tend to suppress the ability of a third party to engage in the political process.

Strategic (favorite-betrayal) effect

The second form of Duverger's law is the effective number of electoral parties or effective number of candidates, measured at the constituency level. This metric measures how competitive an election is, i.e. how many "real choices" each voter has. In this case, Duverger's law can be restated as showing that first-past-the-post voting typically creates smaller . [3]

The use of instant-runoff voting or the two-round system slightly weakens favorite-betrayal incentives in , by allowing voters to support a hopeless candidate in the first round. This initially led Duverger to hypothesize such systems would not be subject to his law. However, contrary to a misconception popular in the United States, it does not eliminate it, and . Two-party systems have remained in Australia, and Ireland

The second challenge to a third party is both statistical and tactical. Duverger presents the example of an election in which 100,000 moderate voters and 80,000 radical voters are to vote for candidates for a single seat or office. If two moderate parties ran candidates and one radical candidate ran (and every voter voted), the radical candidate would tend to win unless one of the moderate candidates gathered fewer than 20,000 votes. Appreciating this risk, moderate voters would be inclined to vote for the moderate candidate they deemed likely to gain more votes, with the goal of defeating the radical candidate. To win, then, either the two moderate parties must merge, or one moderate party must fail, as the voters gravitate to the two strongest parties. [15]

Exceptions

Duverger's original writings conflated various separate principles: the effective number of

Some minor parties in winner-take-all systems have managed to translate their support into winning seats in government by focusing on local races, taking the place of a major party, or changing the political system. [12]

Strength of effect

William Clark and Matt Golder (2006) find the effect largely holds up, noting that different methods of analyzing the data might lead to different conclusions. They emphasize other variables like the nuances of different electoral institutions and the importance that Duverger also placed on sociological factors. [16] Thomas R. Palfrey argued Duverger's law can be proven mathematically at the limit when the number of voters approaches infinity for one single-winner district and where the probability distribution of votes is known (perfect information). [17]

Duverger did not regard this principle as absolute, suggesting instead that plurality would act to delay the emergence of new political forces and would accelerate the elimination of weakening ones, whereas proportional representation would have the opposite effect. [15]

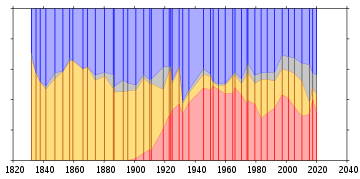

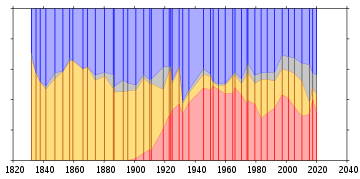

The U.S. system has two major parties which have won, on average, 98% of all state and federal seats. [1] There have only been a few rare elections where a minor party was competitive with the major parties, occasionally replacing one of the major parties in the 19th century. [2] [12]

In Matt Golder's 2016 review of the empirical evidence to-date, he concluded that despite some contradicting cases, the law remains a valid generalization. [18]

Steven R. Reed argued in 2001 that Duverger's law could be observed in Italy, with 80% of electoral districts gradually but significantly shifting towards two major parties. [19] He finds a similar effect in Japan through a slow trial-and-error process that shifted the number of major parties towards the expected outcome. [20]

Eric Dickson and Kenneth Scheve argued in 2007 that Duverger's law is strongest when a society is homogenous or closely divided, but is weakened when multiple intermediate identities exist. [21] As evidence of this, Duhamel cites the case of India, where over 25 percent of voters vote for parties outside the two main alliances. [22]

Two-party politics may also emerge in systems that use a form of proportional representation, with Duverger and others arguing that Duverger's Law mostly represents a limiting factor (like a brake) on the number of major parties in other systems more than a prediction of equilibrium for governments with more proportional representation. [16] [23]

Kenneth Benoit suggested causal influence between electoral and party systems might be bidirectional or in either direction. [24] Josep Colomer agreed, arguing that changes from a plurality system to a proportional system are typically preceded by the emergence of more than two effective parties, and increases in the effective number of parties happen not in the short term, but in the mid-to-long term. [25]

- ^ a b Masket, Seth (Fall 2023). "Giving Minor Parties a Chance". Democracy. 70.

- ^ a b Blake, Aaron (2021-11-25). "Why are there only two parties in American politics?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ a b c Volić, Ismar (2024-04-02). "Duverger's law". Making Democracy Count. Princeton University Press. Ch. 2. doi: 10.2307/jj.7492228. ISBN 978-0-691-24882-0.

- ^ Duverger, Maurice (1964). Political parties: their organization and activity in the modern state. Internet Archive. London : Methuen. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-416-68320-2.

-

^ Herrmann, Michael (2012-04-01).

"Voter uncertainty and failure of Duverger's law: an empirical analysis". Public Choice. 151 (1): 63–90.

doi:

10.1007/s11127-010-9734-2.

ISSN

1573-7101.

Real-world simple plurality elections rarely bear out the strong Duvergerian prediction that, in equilibrium, only two competitors receive votes.

{{ cite journal}}: no-break space character in|title=at position 52 ( help) -

^ Blais, André (2016-04-01).

"Is Duverger's law valid?". French Politics. 14 (1): 126–130.

doi:

10.1057/fp.2015.24.

ISSN

1476-3427.

I show that, contrary to Duverger's law, three or four parties receive at least 5 per cent of the votes in most districts in British and Canadian elections.

-

^ Fey, Mark (1997-03).

"Stability and Coordination in Duverger's Law: A Formal Model of Preelection Polls and Strategic Voting". American Political Science Review. 91 (1): 135–147.

doi:

10.2307/2952264.

ISSN

0003-0554.

I show that in a Bayesian game model of strategic voting there exist non-Duvergerian equilibria in which all three candidates receive votes (in the limit).

{{ cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=( help) - ^ Humes, Brian D. (1990-03-01). "Multi-party competition with exit: A comment on Duverger's Law". Public Choice. 64 (3): 229–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00124368. ISSN 1573-7101.

- ^ Schlesinger, Joseph A.; Schlesinger, Mildred S. (2006). "Maurice Duverger and the Study of Political Parties" (PDF). French Politics. 4: 58–68. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200085. S2CID 145281087. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- ^ Wada, Junichiro (2004-01-14). The Japanese Election System: Three Analytical Perspectives. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780203208595.

- ^ Alston, Eric (2018). "The Legislature and Executive". In Alston, Lee J.; Mueller, Bernardo; Nonnenmacher, Tomas (eds.). Institutional and Organizational Analysis: Concepts and Applications. Cambridge University Press. pp. 173–206. doi: 10.1017/9781316091340.006. ISBN 9781316091340. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Riker, William H. (December 1982). "The Two-party System and Duverger's Law: An Essay on the History of Political Science". American Political Science Review. 76 (4): 753–766. doi: 10.1017/s0003055400189580. JSTOR 1962968. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Rae, Douglas W. (1971). The political consequences of electoral laws (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300015178. LCCN 74161209. OCLC 993822935.

- ^ Dunleavy, Patrick; Diwakar, Rekha (2013). "Analysing multiparty competition in plurality rule elections" (PDF). Party Politics. 19 (6): 855–886. doi: 10.1177/1354068811411026. S2CID 18840573.

- ^ a b Duverger, Maurice (1972). "Factors in a Two-Party and Multiparty System". Party Politics and Pressure Groups. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell. pp. 23–32.

- ^ a b Clark, William Roberts; Golder, Matt (August 2006). "Rehabilitating Duverger's Theory: Testing the Mechanical and Strategic Modifying Effects of Electoral Laws". Comparative Political Studies. 39 (6): 679–708. doi: 10.1177/0010414005278420. ISSN 0010-4140. S2CID 154525800.

- ^ Palfrey, T. (1989) ‘A mathematical proof of Duverger’s law’, in P. Ordeshook (ed.) Models of Strategic Choice in Politics, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 69–91.

- ^ Golder, M. (2016). "Far from equilibrium: The state of the field on electoral system effects on party systems." In E. Herron, R. Pekkanen, & M. Shugart (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Reed, Steven R. (April 2001). "Duverger's Law is Working in Italy". Comparative Political Studies. 34 (3): 312–327. doi: 10.1177/0010414001034003004. S2CID 154808991.

- ^ Reed, Steven R. (1990). "Structure and Behaviour: Extending Duverger's Law to the Japanese Case". British Journal of Political Science. 20 (3): 335–356. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400005871. JSTOR 193914. S2CID 154377379.

- ^ Dickson, Eric S.; Scheve, Kenneth (20 February 2007). "Social Identity, Electoral Institutions and the Number of Candidates" (PDF). British Journal of Political Science. 40 (2): 349–375. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.75.155. doi: 10.1017/s0007123409990354. JSTOR 40649446. S2CID 7107526. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-21. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

-

^

Duhamel, Olivier;

Tusseau, Guillaume (2019).

Droit constitutionnel et institutions politiques [Constitutional law and political institutions] (in French) (5e ed.). Paris:

Éditions du Seuil. p. 297.

ISBN

9782021441932.

OCLC

1127387529.

[L]a loi selon laquelle le scrutin majoritaire à un tour tend à produire le bipartisme ne vaut que dans une société relativement homogène et un État assez centralisé. Dans le cas contraire, le système de parti national se voit concurrencé par des sous-systèmes régionaux.

- ^ Cox, Gary W. (1997). Making votes count: strategic coordination in the world's electoral systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 273–274. ISBN 9780521585163. OCLC 474972505.

- ^ Benoit, Kenneth (2007). "Electoral Laws as Political Consequences: Explaining the Origins and Change of Electoral Institutions". Annual Review of Political Science. 10 (1): 363–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.101608.

- ^ Colomer, Josep M. (2005). "It's Parties that Choose Electoral Systems (or Duverger's Law Upside Down)" (PDF). Political Studies. 53 (1): 1–21. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.563.7631. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00514.x. hdl: 10261/61619. S2CID 12376724. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2006. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

In political science, Duverger's law(s) ( /ˈduvərʒeɪ/ DOO-vər-zhay) describe the kinds of electoral systems that tend to produce two-party systems or competitive elections with voter choice. [1] [2] [3] In its original form, Maurice Duverger argued that first-preference plurality voting in single-member districts would encourage countries to develop a two-party system, while proportional representation would not. [4] This strong form of Duverger's law has since been qualified by political scientists, [5] [6] who have shown that single-member plurality can produce multi-party systems in many situations, [7] [8] while .

Mechanisms

Maurice Duverger identified two reasons why single-member plurality tends to reduce the effective number of candidates in each electoral district: [9] [10] [11] [3]

- Small parties are unable to win seats in a winner-take-all system, which also reduces the incentive to create a new party (the mechanical factor).

- Voters would rather support one of the stronger parties (the strategic factor, which Duverger originally called "psychological").

The first law corresponds to the effect of winner-take-all or most systems (including single-member districts), while the second corresponds to the use of voting systems subject to favorite betrayal.

Mechanical (underrepresentation) effect

Duverger's first observation is that winner-take-all voting produces a mechanical effect where there are fewer parties in , simply because it is more difficult for a small party to win a seat. The smallest number of votes sufficient to win a

The mechanical effect involves single-member districts that inherently produce disproportional outcomes, with . In each individual seat, because it is only possible for a single party to win. As a result, it is possible for only a . This effect can be diminished by increasing the number of districts, a . The results in a cube root law for countries that use single-member districts, which tends to balance the misrepresentation caused by large districts with the

William H. Riker, citing Douglas W. Rae, noted that strong regional parties can lead to more than two parties receiving seats in the national legislature, even if there are only two parties competitive in any single district. [12] [13] In systems outside the United States, like Canada, [12] United Kingdom and India, multiparty parliaments exist due to the growth of minor parties finding strongholds in specific regions, potentially lessening the psychological fear of a wasted vote by voting for a minor party for a legislative seat. [14] Riker credits Canada's highly decentralized system of government as encouraging minor parties to build support by winning seats locally, which then sets the parties up to get representatives in the House of Commons of Canada. [12]

For legislatures where each seat represents a geographical area and the candidate with the most votes wins that seat, minor parties spread fairly evenly across many districts win less representation than geographically concentrated ones with the same overall level of public support. An example of this is the Liberal Democrats in the United Kingdom, whose proportion of seats in the legislature is consistently far below their proportion of the national vote. The Green Party of Canada is another example; the party received about 5% of the popular vote from 2004 to 2011 but had only won one seat (out of 308) in the House of Commons in the same span of time. Another example was seen in the 1992 U.S. presidential election, when Ross Perot's candidacy received zero electoral votes despite receiving 19% of the popular vote. Gerrymandering is sometimes used to try to collect a population of like-minded voters within a geographically cohesive district so that their votes are not "wasted", but tends to require that minor parties have both a geographic concentration and a redistricting process that seeks to represent them. These disadvantages tend to suppress the ability of a third party to engage in the political process.

Strategic (favorite-betrayal) effect

The second form of Duverger's law is the effective number of electoral parties or effective number of candidates, measured at the constituency level. This metric measures how competitive an election is, i.e. how many "real choices" each voter has. In this case, Duverger's law can be restated as showing that first-past-the-post voting typically creates smaller . [3]

The use of instant-runoff voting or the two-round system slightly weakens favorite-betrayal incentives in , by allowing voters to support a hopeless candidate in the first round. This initially led Duverger to hypothesize such systems would not be subject to his law. However, contrary to a misconception popular in the United States, it does not eliminate it, and . Two-party systems have remained in Australia, and Ireland

The second challenge to a third party is both statistical and tactical. Duverger presents the example of an election in which 100,000 moderate voters and 80,000 radical voters are to vote for candidates for a single seat or office. If two moderate parties ran candidates and one radical candidate ran (and every voter voted), the radical candidate would tend to win unless one of the moderate candidates gathered fewer than 20,000 votes. Appreciating this risk, moderate voters would be inclined to vote for the moderate candidate they deemed likely to gain more votes, with the goal of defeating the radical candidate. To win, then, either the two moderate parties must merge, or one moderate party must fail, as the voters gravitate to the two strongest parties. [15]

Exceptions

Duverger's original writings conflated various separate principles: the effective number of

Some minor parties in winner-take-all systems have managed to translate their support into winning seats in government by focusing on local races, taking the place of a major party, or changing the political system. [12]

Strength of effect

William Clark and Matt Golder (2006) find the effect largely holds up, noting that different methods of analyzing the data might lead to different conclusions. They emphasize other variables like the nuances of different electoral institutions and the importance that Duverger also placed on sociological factors. [16] Thomas R. Palfrey argued Duverger's law can be proven mathematically at the limit when the number of voters approaches infinity for one single-winner district and where the probability distribution of votes is known (perfect information). [17]

Duverger did not regard this principle as absolute, suggesting instead that plurality would act to delay the emergence of new political forces and would accelerate the elimination of weakening ones, whereas proportional representation would have the opposite effect. [15]

The U.S. system has two major parties which have won, on average, 98% of all state and federal seats. [1] There have only been a few rare elections where a minor party was competitive with the major parties, occasionally replacing one of the major parties in the 19th century. [2] [12]

In Matt Golder's 2016 review of the empirical evidence to-date, he concluded that despite some contradicting cases, the law remains a valid generalization. [18]

Steven R. Reed argued in 2001 that Duverger's law could be observed in Italy, with 80% of electoral districts gradually but significantly shifting towards two major parties. [19] He finds a similar effect in Japan through a slow trial-and-error process that shifted the number of major parties towards the expected outcome. [20]

Eric Dickson and Kenneth Scheve argued in 2007 that Duverger's law is strongest when a society is homogenous or closely divided, but is weakened when multiple intermediate identities exist. [21] As evidence of this, Duhamel cites the case of India, where over 25 percent of voters vote for parties outside the two main alliances. [22]

Two-party politics may also emerge in systems that use a form of proportional representation, with Duverger and others arguing that Duverger's Law mostly represents a limiting factor (like a brake) on the number of major parties in other systems more than a prediction of equilibrium for governments with more proportional representation. [16] [23]

Kenneth Benoit suggested causal influence between electoral and party systems might be bidirectional or in either direction. [24] Josep Colomer agreed, arguing that changes from a plurality system to a proportional system are typically preceded by the emergence of more than two effective parties, and increases in the effective number of parties happen not in the short term, but in the mid-to-long term. [25]

- ^ a b Masket, Seth (Fall 2023). "Giving Minor Parties a Chance". Democracy. 70.

- ^ a b Blake, Aaron (2021-11-25). "Why are there only two parties in American politics?". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-09-25.

- ^ a b c Volić, Ismar (2024-04-02). "Duverger's law". Making Democracy Count. Princeton University Press. Ch. 2. doi: 10.2307/jj.7492228. ISBN 978-0-691-24882-0.

- ^ Duverger, Maurice (1964). Political parties: their organization and activity in the modern state. Internet Archive. London : Methuen. p. 239. ISBN 978-0-416-68320-2.

-

^ Herrmann, Michael (2012-04-01).

"Voter uncertainty and failure of Duverger's law: an empirical analysis". Public Choice. 151 (1): 63–90.

doi:

10.1007/s11127-010-9734-2.

ISSN

1573-7101.

Real-world simple plurality elections rarely bear out the strong Duvergerian prediction that, in equilibrium, only two competitors receive votes.

{{ cite journal}}: no-break space character in|title=at position 52 ( help) -

^ Blais, André (2016-04-01).

"Is Duverger's law valid?". French Politics. 14 (1): 126–130.

doi:

10.1057/fp.2015.24.

ISSN

1476-3427.

I show that, contrary to Duverger's law, three or four parties receive at least 5 per cent of the votes in most districts in British and Canadian elections.

-

^ Fey, Mark (1997-03).

"Stability and Coordination in Duverger's Law: A Formal Model of Preelection Polls and Strategic Voting". American Political Science Review. 91 (1): 135–147.

doi:

10.2307/2952264.

ISSN

0003-0554.

I show that in a Bayesian game model of strategic voting there exist non-Duvergerian equilibria in which all three candidates receive votes (in the limit).

{{ cite journal}}: Check date values in:|date=( help) - ^ Humes, Brian D. (1990-03-01). "Multi-party competition with exit: A comment on Duverger's Law". Public Choice. 64 (3): 229–238. doi: 10.1007/BF00124368. ISSN 1573-7101.

- ^ Schlesinger, Joseph A.; Schlesinger, Mildred S. (2006). "Maurice Duverger and the Study of Political Parties" (PDF). French Politics. 4: 58–68. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.fp.8200085. S2CID 145281087. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 July 2011. Retrieved 2011-12-17.

- ^ Wada, Junichiro (2004-01-14). The Japanese Election System: Three Analytical Perspectives. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9780203208595.

- ^ Alston, Eric (2018). "The Legislature and Executive". In Alston, Lee J.; Mueller, Bernardo; Nonnenmacher, Tomas (eds.). Institutional and Organizational Analysis: Concepts and Applications. Cambridge University Press. pp. 173–206. doi: 10.1017/9781316091340.006. ISBN 9781316091340. Retrieved September 25, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Riker, William H. (December 1982). "The Two-party System and Duverger's Law: An Essay on the History of Political Science". American Political Science Review. 76 (4): 753–766. doi: 10.1017/s0003055400189580. JSTOR 1962968. Retrieved 12 April 2020.

- ^ Rae, Douglas W. (1971). The political consequences of electoral laws (Rev. ed.). New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 0300015178. LCCN 74161209. OCLC 993822935.

- ^ Dunleavy, Patrick; Diwakar, Rekha (2013). "Analysing multiparty competition in plurality rule elections" (PDF). Party Politics. 19 (6): 855–886. doi: 10.1177/1354068811411026. S2CID 18840573.

- ^ a b Duverger, Maurice (1972). "Factors in a Two-Party and Multiparty System". Party Politics and Pressure Groups. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell. pp. 23–32.

- ^ a b Clark, William Roberts; Golder, Matt (August 2006). "Rehabilitating Duverger's Theory: Testing the Mechanical and Strategic Modifying Effects of Electoral Laws". Comparative Political Studies. 39 (6): 679–708. doi: 10.1177/0010414005278420. ISSN 0010-4140. S2CID 154525800.

- ^ Palfrey, T. (1989) ‘A mathematical proof of Duverger’s law’, in P. Ordeshook (ed.) Models of Strategic Choice in Politics, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 69–91.

- ^ Golder, M. (2016). "Far from equilibrium: The state of the field on electoral system effects on party systems." In E. Herron, R. Pekkanen, & M. Shugart (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Electoral Systems. Oxford University Press.

- ^ Reed, Steven R. (April 2001). "Duverger's Law is Working in Italy". Comparative Political Studies. 34 (3): 312–327. doi: 10.1177/0010414001034003004. S2CID 154808991.

- ^ Reed, Steven R. (1990). "Structure and Behaviour: Extending Duverger's Law to the Japanese Case". British Journal of Political Science. 20 (3): 335–356. doi: 10.1017/S0007123400005871. JSTOR 193914. S2CID 154377379.

- ^ Dickson, Eric S.; Scheve, Kenneth (20 February 2007). "Social Identity, Electoral Institutions and the Number of Candidates" (PDF). British Journal of Political Science. 40 (2): 349–375. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.75.155. doi: 10.1017/s0007123409990354. JSTOR 40649446. S2CID 7107526. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-07-21. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

-

^

Duhamel, Olivier;

Tusseau, Guillaume (2019).

Droit constitutionnel et institutions politiques [Constitutional law and political institutions] (in French) (5e ed.). Paris:

Éditions du Seuil. p. 297.

ISBN

9782021441932.

OCLC

1127387529.

[L]a loi selon laquelle le scrutin majoritaire à un tour tend à produire le bipartisme ne vaut que dans une société relativement homogène et un État assez centralisé. Dans le cas contraire, le système de parti national se voit concurrencé par des sous-systèmes régionaux.

- ^ Cox, Gary W. (1997). Making votes count: strategic coordination in the world's electoral systems. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 273–274. ISBN 9780521585163. OCLC 474972505.

- ^ Benoit, Kenneth (2007). "Electoral Laws as Political Consequences: Explaining the Origins and Change of Electoral Institutions". Annual Review of Political Science. 10 (1): 363–390. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.101608.

- ^ Colomer, Josep M. (2005). "It's Parties that Choose Electoral Systems (or Duverger's Law Upside Down)" (PDF). Political Studies. 53 (1): 1–21. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.563.7631. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2005.00514.x. hdl: 10261/61619. S2CID 12376724. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 February 2006. Retrieved 2009-05-31.