Ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) are protein domains that recognise and bind non- covalently to ubiquitin through protein-protein interactions. As of 2019, a total of 29 types of UBDs had been identified in the human proteome. [2] [3] Most UBDs bind to ubiquitin only weakly, with binding affinities in the low to mid μM range. [4] [5] Proteins containing UBDs are known as ubiquitin-binding proteins or sometimes as "ubiquitin receptors". [2] [4]

Structure

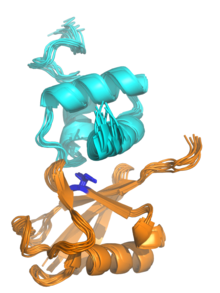

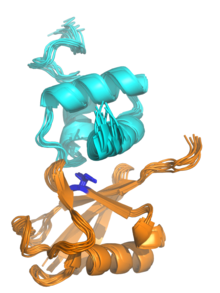

Most UBDs are of small size (often less than 50 amino acids) and adopt many different protein folds from multiple fold classes, including all- alpha, all- beta, and alpha/beta folds. Many UBDs can be roughly classified into four broad categories: alpha-helical structures (in some cases as small as a single helix, as in the ubiquitin-interacting motif); zinc fingers; pleckstrin homology (PH) domains; and domains similar to those in ubiquitin-conjugating (also known as E2) enzymes. Other UBDs not fitting these categories can be SH3 domains, PFU domains, and other structures. [5] [6] Small helical structures are the most common, and examples include ubiquitin-associated domains (UBA), CUE domains, the ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM), the motif interacting with ubiquitin (MIU), and the VHS protein domain. [5]

Binding mechanism

Many UBDs of the UBA family bind to ubiquitin via a hydrophobic patch centred on a particular isoleucine residue (the "Ile44 patch"), [7] although binding to other surface patches has been observed, for example the "Ile36 patch". [8] Zinc finger UBDs have a broader range of binding modes including interactions with polar residues. [5] Because many UBDs have a common or overlapping ubiquitin interaction surface, their interactions are often mutually exclusive; due to steric clashes, more than one UBD cannot physically interact with the same Ile44-centered hydrophobic patch on a single ubiquitin molecule. [5]

Most UBDs described to date bind to monoubiquitin and thus do not show a linkage-preference for the differently linked ubiquitin chains. There are, however, a handful of known, linkage-specific UBDs, that can specifically differentiate between the eight different ubiquitin linkages. This is important as the different linkage types are thought to signal for different molecular processes and linkage-specific recognition of these chains ensures the appropriate cellular response.[ citation needed]

References

- ^ Zhang, Daoning; Raasi, Shahri; Fushman, David (March 2008). "Affinity Makes the Difference: Nonselective Interaction of the UBA Domain of Ubiquilin-1 with Monomeric Ubiquitin and Polyubiquitin Chains". Journal of Molecular Biology. 377 (1): 162–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.029. PMC 2323583. PMID 18241885.

- ^ a b Radley, Eh; Long, J; Gough, Kc; Layfield, R (20 December 2019). "The 'dark matter' of ubiquitin-mediated processes: opportunities and challenges in the identification of ubiquitin-binding domains". Biochemical Society Transactions. 47 (6): 1949–1962. doi: 10.1042/BST20190869. PMID 31829417. S2CID 209328935.

- ^ Zhou, Jiaqi; Xu, Yang; Lin, Shaofeng; Guo, Yaping; Deng, Wankun; Zhang, Ying; Guo, Anyuan; Xue, Yu (4 January 2018). "iUUCD 2.0: an update with rich annotations for ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like conjugations". Nucleic Acids Research. 46 (D1): D447–D453. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1041. PMC 5753239. PMID 29106644.

- ^ a b Santonico, Elena (7 April 2020). "Old and New Concepts in Ubiquitin and NEDD8 Recognition". Biomolecules. 10 (4): 566. doi: 10.3390/biom10040566. PMC 7226360. PMID 32272761.

- ^ a b c d e Dikic I, Wakatsuki S, Walters KJ (2009). "Ubiquitin-binding domains - from structures to functions". Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 10 (10): 659–671. doi: 10.1038/nrm2767. PMC 7359374. PMID 19773779.

- ^ Husnjak, Koraljka; Dikic, Ivan (7 July 2012). "Ubiquitin-Binding Proteins: Decoders of Ubiquitin-Mediated Cellular Functions". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 81 (1): 291–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051810-094654. PMID 22482907.

- ^ Ohno A, et al. (2005). "Structure of the UBA Domain of Dsk2p in Complex with Ubiquitin: Molecular Determinants for Ubiquitin Recognition". Structure. 13 (4): 521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.01.011. PMID 15837191.

- ^ Reyes-Turcu FE, et al. (2006). "The ubiquitin binding domain ZnF UBP recognizes the C-terminal diglycine motif of unanchored ubiquitin". Cell. 124 (6): 1197–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.038. PMID 16564012. S2CID 1312137.

Ubiquitin-binding domains (UBDs) are protein domains that recognise and bind non- covalently to ubiquitin through protein-protein interactions. As of 2019, a total of 29 types of UBDs had been identified in the human proteome. [2] [3] Most UBDs bind to ubiquitin only weakly, with binding affinities in the low to mid μM range. [4] [5] Proteins containing UBDs are known as ubiquitin-binding proteins or sometimes as "ubiquitin receptors". [2] [4]

Structure

Most UBDs are of small size (often less than 50 amino acids) and adopt many different protein folds from multiple fold classes, including all- alpha, all- beta, and alpha/beta folds. Many UBDs can be roughly classified into four broad categories: alpha-helical structures (in some cases as small as a single helix, as in the ubiquitin-interacting motif); zinc fingers; pleckstrin homology (PH) domains; and domains similar to those in ubiquitin-conjugating (also known as E2) enzymes. Other UBDs not fitting these categories can be SH3 domains, PFU domains, and other structures. [5] [6] Small helical structures are the most common, and examples include ubiquitin-associated domains (UBA), CUE domains, the ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM), the motif interacting with ubiquitin (MIU), and the VHS protein domain. [5]

Binding mechanism

Many UBDs of the UBA family bind to ubiquitin via a hydrophobic patch centred on a particular isoleucine residue (the "Ile44 patch"), [7] although binding to other surface patches has been observed, for example the "Ile36 patch". [8] Zinc finger UBDs have a broader range of binding modes including interactions with polar residues. [5] Because many UBDs have a common or overlapping ubiquitin interaction surface, their interactions are often mutually exclusive; due to steric clashes, more than one UBD cannot physically interact with the same Ile44-centered hydrophobic patch on a single ubiquitin molecule. [5]

Most UBDs described to date bind to monoubiquitin and thus do not show a linkage-preference for the differently linked ubiquitin chains. There are, however, a handful of known, linkage-specific UBDs, that can specifically differentiate between the eight different ubiquitin linkages. This is important as the different linkage types are thought to signal for different molecular processes and linkage-specific recognition of these chains ensures the appropriate cellular response.[ citation needed]

References

- ^ Zhang, Daoning; Raasi, Shahri; Fushman, David (March 2008). "Affinity Makes the Difference: Nonselective Interaction of the UBA Domain of Ubiquilin-1 with Monomeric Ubiquitin and Polyubiquitin Chains". Journal of Molecular Biology. 377 (1): 162–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.12.029. PMC 2323583. PMID 18241885.

- ^ a b Radley, Eh; Long, J; Gough, Kc; Layfield, R (20 December 2019). "The 'dark matter' of ubiquitin-mediated processes: opportunities and challenges in the identification of ubiquitin-binding domains". Biochemical Society Transactions. 47 (6): 1949–1962. doi: 10.1042/BST20190869. PMID 31829417. S2CID 209328935.

- ^ Zhou, Jiaqi; Xu, Yang; Lin, Shaofeng; Guo, Yaping; Deng, Wankun; Zhang, Ying; Guo, Anyuan; Xue, Yu (4 January 2018). "iUUCD 2.0: an update with rich annotations for ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like conjugations". Nucleic Acids Research. 46 (D1): D447–D453. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx1041. PMC 5753239. PMID 29106644.

- ^ a b Santonico, Elena (7 April 2020). "Old and New Concepts in Ubiquitin and NEDD8 Recognition". Biomolecules. 10 (4): 566. doi: 10.3390/biom10040566. PMC 7226360. PMID 32272761.

- ^ a b c d e Dikic I, Wakatsuki S, Walters KJ (2009). "Ubiquitin-binding domains - from structures to functions". Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 10 (10): 659–671. doi: 10.1038/nrm2767. PMC 7359374. PMID 19773779.

- ^ Husnjak, Koraljka; Dikic, Ivan (7 July 2012). "Ubiquitin-Binding Proteins: Decoders of Ubiquitin-Mediated Cellular Functions". Annual Review of Biochemistry. 81 (1): 291–322. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-051810-094654. PMID 22482907.

- ^ Ohno A, et al. (2005). "Structure of the UBA Domain of Dsk2p in Complex with Ubiquitin: Molecular Determinants for Ubiquitin Recognition". Structure. 13 (4): 521–532. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.01.011. PMID 15837191.

- ^ Reyes-Turcu FE, et al. (2006). "The ubiquitin binding domain ZnF UBP recognizes the C-terminal diglycine motif of unanchored ubiquitin". Cell. 124 (6): 1197–1208. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.038. PMID 16564012. S2CID 1312137.