Suzanne Ferrière | |

|---|---|

| |

| Signature | |

|

Anne Suzanne "Lili" Ferrière (22 March 1886, Geneva – 13 March 1970, Geneva) was a Swiss dance teacher of Dalcroze eurhythmics and a humanitarian activist from a prominent Genevan family. As only the third female member of the governing body of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), she helped to pave the way towards gender equality in the organisation. [1]

Ferrière also contributed to establishing the Save the Children International Union, the International Social Service for migrants, and the International Union for Child Welfare. During the Second World War she became an outspoken advocate inside the ICRC leadership to publicly denounce Nazi Germany's system of extermination and concentration camps. [2] [3]

Life

Family background and early years

The Ferrière family reportedly originated from the Normandy and moved to Besançon in Eastern France, close to the Jura Mountains and the border with Switzerland, around 1700. [4] From there they arrived in the republic of Geneva some forty years later. Since they were a family of Protestant pastors, it seems plausible that they escaped repressions which arose after Louis XIV in 1685 revoked the 1598 Edict of Nantes, which had restored some civil rights to the Huguenots. In 1781, the family obtained Genevan citizenship. [1]

Suzanne Ferrière's father Louis (1842–1928) was a pastor as well, who supported the philanthropic Union nationale évangélique and the social Christianity movement. [1] His wife Hedwig Marie Therese, née Faber (1859–1928), hailed from Vienna, [5] and her older sister Adolphine was married to his younger brother Frederic. [6] Suzanne was the second-oldest child of five. She had two brothers and two sisters: Jean Auguste (1884–1968), Louis Emmanuel (1887–1963), Marguerite Louise Hedwige (1890–1984), and Juliette Jeanne Adolphine (1895–1970). [7] Anne Suzanne was apparently named after her great-aunts Anna (1803–1890) and Suzanne Ferrière (1806–1883), who were teachers. [8] [9] She grew up and lived all of her life in the Florissant part of Geneva's Champel quarter, [7] where the family was traditionally based. [10] In 1904, she finished school at Geneva's Ecole secondaire et supérieure des jeunes filles. [11]

In subsequent years, Suzanne Ferrière became a student of the Swiss composer Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, who was Professor of Harmony at the Conservatoire de Musique de Genève since 1892. In his solfège courses he tested many of his pedagogical ideas. In 1910, he left and established his own academy in Hellerau, near Dresden. Suzanne Ferrière was one of the 46 students from Geneva who joined Jaques-Dalcroze. [12] In July 1913 she obtained her diploma in rhythmic and plastic gymnastic with a special mention. [13] She immediately started teaching [14] and developed in her class her own variant of eurhythmics, which was inspired by dancing elements and became known as exercices de plastique animée. [15] [16]

In May 1914, Ferrière co-directed a eurythmic performance in the great vestibule of Geneva's Musée d’art et d’histoire (MAH) to celebrate the cenentiary of the city's and canton's admission to the Swiss Confederation at the Vienna Congress. [17]

First World War

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the ICRC under its president Gustave Ador established the International Prisoners-of-War Agency (IPWA) to trace POWs and to re-establish communications with their respective families. The Austrian writer and pacifist Stefan Zweig described the situation in 1914 at the Geneva headquarters of the ICRC as follows:

«Hardly had the first blows been struck when cries of anguish from all lands began to be heard in Switzerland. Thousands who were without news of fathers, husbands, and sons in the battlefields, stretched despairing arms into the void. By hundreds, by thousands, by tens of thousands, letters and telegrams poured into the little House of the Red Cross in Geneva, the only international rallying point that still remained. Isolated, like stormy petrels, came the first inquiries for missing relatives; then these inquiries themselves became a storm. The letters arrived in sackfuls. Nothing had been prepared for dealing with such an inundation of misery. The Red Cross had no space, no organization, no system, and above all no helpers.» [18]

By the end of the same year, the Agency had some 1,200 volunteers who worked in the Musée Rath of Geneva, amongst them the French writer and pacifist Romain Rolland. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for 1915, he donated half of the prize money to the Agency. [19] Most of the staff were women. Some of them came from the Patrician class of Geneva and joined the IPWA because of male relatives in high ICRC positions, which was all-male for more than half century. This group included female pioneers like Marguerite Cramer, Marguerite van Berchem, and Suzanne Ferrière.

The IPWA mandate was based on resolution VI of the 9th Red Cross movement conference of Washington in 1912 and hence limited to military personnel. However, Ferrière's uncle, the committee member and medical doctor Frédéric Ferrière, founded a civilian section against the advice of other committee members. [20] Ferrière worked in the IPWA under the supervision of her uncle until 1915. [21] However, she then gave up that commitment and followed the call of Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, who sent her to the United States. There she founded still in 1915 the New York Dalcroze School of Music and became its first director. [22] [23] [24]

Between the World Wars

After her return to Switzerland in 1918 Ferrière volunteered in the ICRC relief section and thus came to know with Eglantyne Jebb (1876–1928). Jebb, a British social reformer, had founded the Save the Children Fund (SCF) organisation at the end of the war to relieve the effects of famine in Austria-Hungary and Germany. [21] In September 1919, Ferrière arranged a meeting between her uncle Frederic and Jebb, who explained her goal to create a neutral international institution for the administration of child welfare:

«In November with Ferriere's support the ICRC took three unusual steps. It offered the SCF its ‘patronage’, it consented ‘to receive the funds’ on the SCF's behalf and it allowed the SCF to retain ‘independence of appeal and independence of allocation’. The patronage of the ICRC enabled Eglantyne to create an international ‘central agency’, which she called the Save the Children Fund International Union (SCIU).» [25]

In addition, Ferrière worked with Jebb to found the International Union for Child Welfare (IUCW), of which she became the assistant secretary-general. [21] The women developed such a close relationship that Jebb called Ferrière her "international sister". [26] [25]

In 1920, Ferrière also played a key role when the Young Women Christian Association founded the International Migration Service (IMS)—later renamed the International Social Service (ISS)—as a network of social work agencies helping migrant women and children. The ISS gained its status as an international non-governmental organization (NGO) in 1924 and moved its headquarters from London to Geneva in the following year. Ferrière became its secretary-general and especially advocated for an international socio-legal framework for cross-border family maintenance claims. [27]

Travels abroad

In her capacities as a leading representative for the ICRC, the IUCW, and the IMS, Ferrière conducted a number of missions to foreign countries during the 1920s. In January and February 1921, she went to Scandinavia in her capacity as assistant secretary-general of the IUCW. In January and February 1922, she likewise travelled to Moscow and Saratov in Russia to assess the situation in the famine-stricken region. [28] From September until December of that year, she explored the conditions in Ukraine as well. [29] In April 1923, she visited the French-occupied Ruhr area of Germany. [28]

Starting from December 1923, Ferrière toured Latin America for ten months as a delegate of the ICRC to visit the newly founded national red ross societies, crossing over the Andes on donkey-back. The trip led her from Brazil to Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, and Venezuela. After her travels, Ferrière continually stressed the social role that women played in those countries. [30] In May 1929, Ferrière visited the French colonies of Lebanon and Syria to evaluate the situation with regard to the many Armenian genocide survivors who newly arrived from Turkey. [31]

In August 1925, Ferrière was elected a member of the ICRC as successor to her uncle Frédéric Ferrière, who had died in the year before. She was only the third woman ever to join the governing body of the organisation after Marguerite Cramer had been elected in 1919. When Frick-Cramer had moved to Germany after her marriage and therefore stepped down in late 1922, the nurse, feminist and suffragette Pauline Chaponnière-Chaix (1850-1934) succeeded her as the second ever female ICRC member. [1] In 1926, Ferrière was also elected a General Council Member of the Save the Children Fund, which she remained until 1937. [25] Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Ferrière was also chosen on several occasions by Giuseppe Motta to be part of the delegation that represented Switzerland at the League of Nations in Geneva. [32] [33] Motta headed the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs during those two decades. She was its first female member [34] and served as its expert on social [35] and humanitarian issues. [36]

When Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party came to power in Germany in January 1933, the ICRC was faced with the question how to deal with the repressive system. Ferrière belonged to the faction within the ICRC leadership that pushed for interventions in favour of political detainees. Her brother Louis had inspected the conditions in a Vienna prison in 1934 on behalf of the ICRC and thus created a precedent, to which she pointed during a meeting of the ICRC members in February 1935. One month later, the committee transformed its working group for civilians into one for political detainees. Both Ferrière and Frick-Cramer, who was still an honorary member of the ICRC, were members of that team. [2] However, their faction of idealists within the ICRC leadership gradually lost influence vis-à-vis the "pragmatists" led by ICRC president Max Huber. [37]

In September 1935, during a meeting of the ICRC leadership in which the upcoming visit of an ICRC delegation to Nazi Germany was discussed,

«the two women in the meeting, Suzanne Ferrière and Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, stated that the ICRC should at least do everything to give news to the families of the inmates.» [3]

However, the delegation led by Carl Jacob Burckhardt only recorded a "mild critique" to its Nazi hosts. [38] In late 1938, Ferrière started an initiative in aid of Jewish refugees in various countries, but faced internal opposition. In February 1939, she visited Czechoslovakia in her capacity as secretary-general of the IMS and upon her return doubled down on her pledges to support refugees in their quest for safe havens. However, the ICRC's top leaders once more opposed her recommendations. [2]

Second World War

The International Prisoners-of-War Agency (IWPA) was re-activated two weeks after the beginning of the Second World War as the Central Agency for Prisoners of War, now based on the mandate from the 1929 Geneva Convention. Ferrière succeeded her late uncle Frédéric Ferrière and became the director of the department for missing civilians. She also instituted a new family messaging system. [21]

In autumn 1941, Ferrière in her capacity as vice-president of the IMS informed the British Red Cross that Jewish emigration from Nazi-occupied Europe had been halted. [2] In May 1942, Ferriére, Frick-Cramer (who had returned in 1939 as a regular member after 17 years) and fellow member Alec Cramer presented a memorandum to the committee in which they promoted increased support for Jews in Europe. Subsequently, the ICRC revived its working group for POWs and detained civilians, with Ferrière holding the dossier for non-detained civilians. By autumn of that year, the ICRC leadership—including Ferrière—received reports about the systematic extermination of Jews by Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe, the so-called Final Solution. While a large majority of the ICRC's about two dozen members at its general assembly on 14 October 1942—especially its female members Ferrière, Frick-Cramer, Lucie Odier, and Renée Bordier—was in favour of a public protest, Burckhardt and Switzerland's President Philipp Etter firmly denied that request. [2] [3]

In early 1943, Ferrière and her fellow female ICRC pioneer Odier—a nursing expert, who had become the fourth ever female member of the ICRC in 1930—conducted a joint mission to the Middle East and Africa to assess the situation of civilian detainees. Their tour of three months duration included stops in Istanbul, Ankara, Cairo, Jerusalem, Beirut, Johannesburg, Salisbury, and Nairobi. [39] However, Ferrière's standing inside the organisation became diminished: when the executive committee established a department for special assistance to civilian detainees in early 1944, Ferrière as well as her fellow experts Frick-Cramer and Odier were left out of it. [2]

Post-WWII

In 1945, Ferrière gave up her post as the secretary-general of the IMS/ISS, but remained active in the organisation as a deputy-director. [32] In September 1951, Ferrière resigned as ICRC member for age reasons [1] and was appointed an honorary member instead. [2] In 1955, she also resigned as deputy-director of the IMS/ISS, but remained an adviser of the organisation. [32]

When she died in March 1970 at the age of 83 years, the obituary in the International Review of the Red Cross honoured her as a

«a warmhearted woman who had devoted her life to her fellow men with calm courage and exemplary modesty.» [21]

References

- ^ a b c d e Fiscalini, Diego (1985). Des élites au service d'une cause humanitaire : le Comité International de la Croix-Rouge (in French). Geneva: Université de Genève, faculté des lettres, département d'histoire. pp. 24, 160–162.

- ^ a b c d e f g Favez, Jean-Claude (1999). The Red Cross and the Holocaust. Translated by Fletcher, John; Fletcher, Beryl. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–19, 24, 29, 35, 39–40, 48, 50, 57–59, 64, 68, 79, 88, 101, 107–108, 115, 117, 186, 225, 227, 243, 248, 286–287. ISBN 2735108384.

- ^ a b c Steinacher, Gerald (2017). Humanitarians at War. The Red Cross in the Shadow of the Holocaust. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 39, 44, 47. ISBN 978-0-19-870493-5.

- ^ Ferrière, François. "Généalogie de la famille Ferrière (de Genève)". archives-ferriere.nexgate.ch. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Hedwige _ , Marie, Thérese, C." Geneanet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Adolphine _ , Thérèse, Caroline, Katharine Faber". Geneanet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ a b Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Anne Suzanne (Lili) Ferriere". Geneanet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Anna [ Ferrière ] Ferriere". Geneanet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Louise _Susanne_[ Ferrière ] Ferriere". Geneanet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

-

^ El Wakil, Leila (1989). Bâtir la campagne: Genève 1800–1860. Geneva.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher ( link) - ^ "Chronique locale: Promotions — Ecole secondaire et supérieure des jeunes filles". La Tribune de Genève. 26 (155). 7 July 1904. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Kamp, Johannes-Martin (1995). Kinderrepubliken (in German). Opladen: Leske + Budrich. p. 332. ISBN 3-8100-1357-9.

- ^ "Institut Jaques-Dalcroze à Hellerau". La Tribune de Genève. 35 (162): 5. 15 July 1913. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ Berchtold, Alfred (2000). Emile Jaques-Dalcroze et son temps. Lausanne: L'AGE D'HOMME. pp. 118, 185. ISBN 978-2825113547.

- ^ "Methode Jaques-Dalcroze (MJD) – Orff-Schulwerk" (in German). Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Jaques-Dalcroze, Émile (1917). Méthode Jaques-Dalcroze: Exercices de plastique animée – En collaboration pour le classement des exercices et principes avec Mlle Suzanne Ferrière. Lausanne: Jobin & Cie, Sandoz, Jobin.

- ^ "La fête de juin - les débuts de la rythmique". La Tribune de Genève. 36 (108): 4. 12 May 1914. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Zweig, Stefan (1921). Romain Rolland; the man and his work. Translated by Eden, Paul; Cedar, Paul. New York: T. Seltzer. p. 268.

- ^ Schazmann, Paul-Emile (February 1955). "Romain Rolland et la Croix-Rouge: Romain Rolland, Collaborateur de l'Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross (in French). 37 (434): 140–143. doi: 10.1017/S1026881200125735. S2CID 144703916. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, Adolphe (1948). Le Dr Frédéric Ferrière. Son action à la Croix-Rouge internationale en faveur des civils victimes de la guerre (in French). Geneva: Editions Suzerenne, Sarl. pp. 27–41.

- ^ a b c d e "Death of Miss S. Ferriere, Honorary Member of the ICRC" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 109: 210–211. April 1970. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Becknell, Arthur F. (1970). A History of the development of Dalcroze in the United States and its influence on the public school music program. Michigan: University of Michigan. pp. 152–162.

- ^ Thomas, Nathan (1995). Dalcroze Eurhythmics and Rhythm Training for Actors in American Universities. East Lansing: Michigan State University. Department of Theatre. p. 48.

- ^ Wieland Howe, Sondra (2014). Women Music Educators in the United States: A History. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press. p. 246. ISBN 9780810888470.

- ^ a b c Mahood, Linda (2009). Feminism and Voluntary Action: Eglantyne Jebb and Save the Children, 1876–1928. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 173, 218, 257–258. ISBN 9780230525603.

- ^ George, Anne (9 February 2017), Suzanne Ferriere (d 1970), ICRC, IUCW, Save the Children Fund supporter, SCF/P/2/2 page 204, Cadbury Research Library, Cadbury Research Library, archived from the original on 15 July 2021, retrieved 30 June 2021

- ^ Banu, Roxana (3 March 2021). "The Role of the International Social Service in the History of Private International Law". International Social Service USA. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Fonds: Union internationale de secours aux enfants – UISE – Union internationale de protection de l'enfance – UIPE – Série 35 / 123". Les Archives d'Etat de Genève. 737+and+ORIGINE=SERIE')&m=35&order=NATIVE('CDOCA,NUMSER')&type=SERIE&start=51 Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ' ^ "Fonds: Union internationale de secours aux enfants – UISE – Union internationale de protection de l'enfance – UIPE – Série 107 / 123". Les Archives d'Etat de Genève (in French). 737+and+ORIGINE=SERIE )&m=107&order=NATIVE('CDOCA,NUMSER')&type=SERIE&start=101 Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, Suzanne (September 1924). "Les Croix-Rouges de l'Amérique du Sud" (PDF). Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge (in French). 6 (71): 853–870. doi: 10.1017/S1026881200073402. S2CID 145657730. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, Suzanne (January 1930). "Voyage en Syrie" (PDF). Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge (in French). 12 (133): 7–14. doi: 10.1017/S1026881200043543. S2CID 129036333. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Suzanne Ferrière". Journal de Genève. 63: 15. 17 March 1970. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "La délégation suisse à la S.D.N". Le Jura. 88 (109): 2. 13 September 1938. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Congres Internationaux". Journal et Feuille d'Avis du Valais et du Sion: 2. 6 September 1937. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Die Delegation für die Völkerbundsversammlung". Neue Zürcher Nachrichten (in German). Vol. 145. 24 June 1939. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "La Suisse à la Société des nations". La Liberté. 145: 6. 24 June 1939. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Rauh, Cornelia (2009). Schweizer Aluminium für Hitlers Krieg? Zur Geschichte der "Alusuisse" 1918–1950 (in German). Munich: Beck. ISBN 9783406522017.

- ^ Steinacher, Gerald (29 July 2017). "The Red Cross in Nazi Germany". OUPblog. Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Odier, Lucie (September 1943). "Mission en Afrique" (PDF). Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge et Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge (in French). 25 (297): 730–743. doi: 10.1017/S1026881200015919. S2CID 145075925. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

External links

- Letter from Suzanne Ferrière to Carl Jacob Burckhardt – in French, dated 15 October 1938 – from Burckhardt's bequest at the library of the University of Basel

- Suzanne Ferrière in the Dodis data bank of the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- Portrait photo of Ferrière from her later years in the ICRC Audiovisual Archives

Suzanne Ferrière | |

|---|---|

| |

| Signature | |

|

Anne Suzanne "Lili" Ferrière (22 March 1886, Geneva – 13 March 1970, Geneva) was a Swiss dance teacher of Dalcroze eurhythmics and a humanitarian activist from a prominent Genevan family. As only the third female member of the governing body of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), she helped to pave the way towards gender equality in the organisation. [1]

Ferrière also contributed to establishing the Save the Children International Union, the International Social Service for migrants, and the International Union for Child Welfare. During the Second World War she became an outspoken advocate inside the ICRC leadership to publicly denounce Nazi Germany's system of extermination and concentration camps. [2] [3]

Life

Family background and early years

The Ferrière family reportedly originated from the Normandy and moved to Besançon in Eastern France, close to the Jura Mountains and the border with Switzerland, around 1700. [4] From there they arrived in the republic of Geneva some forty years later. Since they were a family of Protestant pastors, it seems plausible that they escaped repressions which arose after Louis XIV in 1685 revoked the 1598 Edict of Nantes, which had restored some civil rights to the Huguenots. In 1781, the family obtained Genevan citizenship. [1]

Suzanne Ferrière's father Louis (1842–1928) was a pastor as well, who supported the philanthropic Union nationale évangélique and the social Christianity movement. [1] His wife Hedwig Marie Therese, née Faber (1859–1928), hailed from Vienna, [5] and her older sister Adolphine was married to his younger brother Frederic. [6] Suzanne was the second-oldest child of five. She had two brothers and two sisters: Jean Auguste (1884–1968), Louis Emmanuel (1887–1963), Marguerite Louise Hedwige (1890–1984), and Juliette Jeanne Adolphine (1895–1970). [7] Anne Suzanne was apparently named after her great-aunts Anna (1803–1890) and Suzanne Ferrière (1806–1883), who were teachers. [8] [9] She grew up and lived all of her life in the Florissant part of Geneva's Champel quarter, [7] where the family was traditionally based. [10] In 1904, she finished school at Geneva's Ecole secondaire et supérieure des jeunes filles. [11]

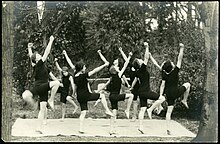

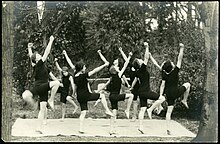

In subsequent years, Suzanne Ferrière became a student of the Swiss composer Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, who was Professor of Harmony at the Conservatoire de Musique de Genève since 1892. In his solfège courses he tested many of his pedagogical ideas. In 1910, he left and established his own academy in Hellerau, near Dresden. Suzanne Ferrière was one of the 46 students from Geneva who joined Jaques-Dalcroze. [12] In July 1913 she obtained her diploma in rhythmic and plastic gymnastic with a special mention. [13] She immediately started teaching [14] and developed in her class her own variant of eurhythmics, which was inspired by dancing elements and became known as exercices de plastique animée. [15] [16]

In May 1914, Ferrière co-directed a eurythmic performance in the great vestibule of Geneva's Musée d’art et d’histoire (MAH) to celebrate the cenentiary of the city's and canton's admission to the Swiss Confederation at the Vienna Congress. [17]

First World War

Shortly after the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, the ICRC under its president Gustave Ador established the International Prisoners-of-War Agency (IPWA) to trace POWs and to re-establish communications with their respective families. The Austrian writer and pacifist Stefan Zweig described the situation in 1914 at the Geneva headquarters of the ICRC as follows:

«Hardly had the first blows been struck when cries of anguish from all lands began to be heard in Switzerland. Thousands who were without news of fathers, husbands, and sons in the battlefields, stretched despairing arms into the void. By hundreds, by thousands, by tens of thousands, letters and telegrams poured into the little House of the Red Cross in Geneva, the only international rallying point that still remained. Isolated, like stormy petrels, came the first inquiries for missing relatives; then these inquiries themselves became a storm. The letters arrived in sackfuls. Nothing had been prepared for dealing with such an inundation of misery. The Red Cross had no space, no organization, no system, and above all no helpers.» [18]

By the end of the same year, the Agency had some 1,200 volunteers who worked in the Musée Rath of Geneva, amongst them the French writer and pacifist Romain Rolland. When he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature for 1915, he donated half of the prize money to the Agency. [19] Most of the staff were women. Some of them came from the Patrician class of Geneva and joined the IPWA because of male relatives in high ICRC positions, which was all-male for more than half century. This group included female pioneers like Marguerite Cramer, Marguerite van Berchem, and Suzanne Ferrière.

The IPWA mandate was based on resolution VI of the 9th Red Cross movement conference of Washington in 1912 and hence limited to military personnel. However, Ferrière's uncle, the committee member and medical doctor Frédéric Ferrière, founded a civilian section against the advice of other committee members. [20] Ferrière worked in the IPWA under the supervision of her uncle until 1915. [21] However, she then gave up that commitment and followed the call of Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, who sent her to the United States. There she founded still in 1915 the New York Dalcroze School of Music and became its first director. [22] [23] [24]

Between the World Wars

After her return to Switzerland in 1918 Ferrière volunteered in the ICRC relief section and thus came to know with Eglantyne Jebb (1876–1928). Jebb, a British social reformer, had founded the Save the Children Fund (SCF) organisation at the end of the war to relieve the effects of famine in Austria-Hungary and Germany. [21] In September 1919, Ferrière arranged a meeting between her uncle Frederic and Jebb, who explained her goal to create a neutral international institution for the administration of child welfare:

«In November with Ferriere's support the ICRC took three unusual steps. It offered the SCF its ‘patronage’, it consented ‘to receive the funds’ on the SCF's behalf and it allowed the SCF to retain ‘independence of appeal and independence of allocation’. The patronage of the ICRC enabled Eglantyne to create an international ‘central agency’, which she called the Save the Children Fund International Union (SCIU).» [25]

In addition, Ferrière worked with Jebb to found the International Union for Child Welfare (IUCW), of which she became the assistant secretary-general. [21] The women developed such a close relationship that Jebb called Ferrière her "international sister". [26] [25]

In 1920, Ferrière also played a key role when the Young Women Christian Association founded the International Migration Service (IMS)—later renamed the International Social Service (ISS)—as a network of social work agencies helping migrant women and children. The ISS gained its status as an international non-governmental organization (NGO) in 1924 and moved its headquarters from London to Geneva in the following year. Ferrière became its secretary-general and especially advocated for an international socio-legal framework for cross-border family maintenance claims. [27]

Travels abroad

In her capacities as a leading representative for the ICRC, the IUCW, and the IMS, Ferrière conducted a number of missions to foreign countries during the 1920s. In January and February 1921, she went to Scandinavia in her capacity as assistant secretary-general of the IUCW. In January and February 1922, she likewise travelled to Moscow and Saratov in Russia to assess the situation in the famine-stricken region. [28] From September until December of that year, she explored the conditions in Ukraine as well. [29] In April 1923, she visited the French-occupied Ruhr area of Germany. [28]

Starting from December 1923, Ferrière toured Latin America for ten months as a delegate of the ICRC to visit the newly founded national red ross societies, crossing over the Andes on donkey-back. The trip led her from Brazil to Argentina, Uruguay, Chile, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, and Venezuela. After her travels, Ferrière continually stressed the social role that women played in those countries. [30] In May 1929, Ferrière visited the French colonies of Lebanon and Syria to evaluate the situation with regard to the many Armenian genocide survivors who newly arrived from Turkey. [31]

In August 1925, Ferrière was elected a member of the ICRC as successor to her uncle Frédéric Ferrière, who had died in the year before. She was only the third woman ever to join the governing body of the organisation after Marguerite Cramer had been elected in 1919. When Frick-Cramer had moved to Germany after her marriage and therefore stepped down in late 1922, the nurse, feminist and suffragette Pauline Chaponnière-Chaix (1850-1934) succeeded her as the second ever female ICRC member. [1] In 1926, Ferrière was also elected a General Council Member of the Save the Children Fund, which she remained until 1937. [25] Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, Ferrière was also chosen on several occasions by Giuseppe Motta to be part of the delegation that represented Switzerland at the League of Nations in Geneva. [32] [33] Motta headed the Swiss Federal Department of Foreign Affairs during those two decades. She was its first female member [34] and served as its expert on social [35] and humanitarian issues. [36]

When Adolf Hitler and his Nazi Party came to power in Germany in January 1933, the ICRC was faced with the question how to deal with the repressive system. Ferrière belonged to the faction within the ICRC leadership that pushed for interventions in favour of political detainees. Her brother Louis had inspected the conditions in a Vienna prison in 1934 on behalf of the ICRC and thus created a precedent, to which she pointed during a meeting of the ICRC members in February 1935. One month later, the committee transformed its working group for civilians into one for political detainees. Both Ferrière and Frick-Cramer, who was still an honorary member of the ICRC, were members of that team. [2] However, their faction of idealists within the ICRC leadership gradually lost influence vis-à-vis the "pragmatists" led by ICRC president Max Huber. [37]

In September 1935, during a meeting of the ICRC leadership in which the upcoming visit of an ICRC delegation to Nazi Germany was discussed,

«the two women in the meeting, Suzanne Ferrière and Renée-Marguerite Frick-Cramer, stated that the ICRC should at least do everything to give news to the families of the inmates.» [3]

However, the delegation led by Carl Jacob Burckhardt only recorded a "mild critique" to its Nazi hosts. [38] In late 1938, Ferrière started an initiative in aid of Jewish refugees in various countries, but faced internal opposition. In February 1939, she visited Czechoslovakia in her capacity as secretary-general of the IMS and upon her return doubled down on her pledges to support refugees in their quest for safe havens. However, the ICRC's top leaders once more opposed her recommendations. [2]

Second World War

The International Prisoners-of-War Agency (IWPA) was re-activated two weeks after the beginning of the Second World War as the Central Agency for Prisoners of War, now based on the mandate from the 1929 Geneva Convention. Ferrière succeeded her late uncle Frédéric Ferrière and became the director of the department for missing civilians. She also instituted a new family messaging system. [21]

In autumn 1941, Ferrière in her capacity as vice-president of the IMS informed the British Red Cross that Jewish emigration from Nazi-occupied Europe had been halted. [2] In May 1942, Ferriére, Frick-Cramer (who had returned in 1939 as a regular member after 17 years) and fellow member Alec Cramer presented a memorandum to the committee in which they promoted increased support for Jews in Europe. Subsequently, the ICRC revived its working group for POWs and detained civilians, with Ferrière holding the dossier for non-detained civilians. By autumn of that year, the ICRC leadership—including Ferrière—received reports about the systematic extermination of Jews by Nazi Germany in Eastern Europe, the so-called Final Solution. While a large majority of the ICRC's about two dozen members at its general assembly on 14 October 1942—especially its female members Ferrière, Frick-Cramer, Lucie Odier, and Renée Bordier—was in favour of a public protest, Burckhardt and Switzerland's President Philipp Etter firmly denied that request. [2] [3]

In early 1943, Ferrière and her fellow female ICRC pioneer Odier—a nursing expert, who had become the fourth ever female member of the ICRC in 1930—conducted a joint mission to the Middle East and Africa to assess the situation of civilian detainees. Their tour of three months duration included stops in Istanbul, Ankara, Cairo, Jerusalem, Beirut, Johannesburg, Salisbury, and Nairobi. [39] However, Ferrière's standing inside the organisation became diminished: when the executive committee established a department for special assistance to civilian detainees in early 1944, Ferrière as well as her fellow experts Frick-Cramer and Odier were left out of it. [2]

Post-WWII

In 1945, Ferrière gave up her post as the secretary-general of the IMS/ISS, but remained active in the organisation as a deputy-director. [32] In September 1951, Ferrière resigned as ICRC member for age reasons [1] and was appointed an honorary member instead. [2] In 1955, she also resigned as deputy-director of the IMS/ISS, but remained an adviser of the organisation. [32]

When she died in March 1970 at the age of 83 years, the obituary in the International Review of the Red Cross honoured her as a

«a warmhearted woman who had devoted her life to her fellow men with calm courage and exemplary modesty.» [21]

References

- ^ a b c d e Fiscalini, Diego (1985). Des élites au service d'une cause humanitaire : le Comité International de la Croix-Rouge (in French). Geneva: Université de Genève, faculté des lettres, département d'histoire. pp. 24, 160–162.

- ^ a b c d e f g Favez, Jean-Claude (1999). The Red Cross and the Holocaust. Translated by Fletcher, John; Fletcher, Beryl. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 18–19, 24, 29, 35, 39–40, 48, 50, 57–59, 64, 68, 79, 88, 101, 107–108, 115, 117, 186, 225, 227, 243, 248, 286–287. ISBN 2735108384.

- ^ a b c Steinacher, Gerald (2017). Humanitarians at War. The Red Cross in the Shadow of the Holocaust. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 39, 44, 47. ISBN 978-0-19-870493-5.

- ^ Ferrière, François. "Généalogie de la famille Ferrière (de Genève)". archives-ferriere.nexgate.ch. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Hedwige _ , Marie, Thérese, C." Geneanet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Adolphine _ , Thérèse, Caroline, Katharine Faber". Geneanet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ a b Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Anne Suzanne (Lili) Ferriere". Geneanet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 29 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Anna [ Ferrière ] Ferriere". Geneanet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, François. "Family tree of Louise _Susanne_[ Ferrière ] Ferriere". Geneanet. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

-

^ El Wakil, Leila (1989). Bâtir la campagne: Genève 1800–1860. Geneva.

{{ cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher ( link) - ^ "Chronique locale: Promotions — Ecole secondaire et supérieure des jeunes filles". La Tribune de Genève. 26 (155). 7 July 1904. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021 – via e-newspaperarchives.ch.

- ^ Kamp, Johannes-Martin (1995). Kinderrepubliken (in German). Opladen: Leske + Budrich. p. 332. ISBN 3-8100-1357-9.

- ^ "Institut Jaques-Dalcroze à Hellerau". La Tribune de Genève. 35 (162): 5. 15 July 1913. Archived from the original on 5 September 2021. Retrieved 5 September 2021.

- ^ Berchtold, Alfred (2000). Emile Jaques-Dalcroze et son temps. Lausanne: L'AGE D'HOMME. pp. 118, 185. ISBN 978-2825113547.

- ^ "Methode Jaques-Dalcroze (MJD) – Orff-Schulwerk" (in German). Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Jaques-Dalcroze, Émile (1917). Méthode Jaques-Dalcroze: Exercices de plastique animée – En collaboration pour le classement des exercices et principes avec Mlle Suzanne Ferrière. Lausanne: Jobin & Cie, Sandoz, Jobin.

- ^ "La fête de juin - les débuts de la rythmique". La Tribune de Genève. 36 (108): 4. 12 May 1914. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Zweig, Stefan (1921). Romain Rolland; the man and his work. Translated by Eden, Paul; Cedar, Paul. New York: T. Seltzer. p. 268.

- ^ Schazmann, Paul-Emile (February 1955). "Romain Rolland et la Croix-Rouge: Romain Rolland, Collaborateur de l'Agence internationale des prisonniers de guerre" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross (in French). 37 (434): 140–143. doi: 10.1017/S1026881200125735. S2CID 144703916. Archived from the original on 23 April 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, Adolphe (1948). Le Dr Frédéric Ferrière. Son action à la Croix-Rouge internationale en faveur des civils victimes de la guerre (in French). Geneva: Editions Suzerenne, Sarl. pp. 27–41.

- ^ a b c d e "Death of Miss S. Ferriere, Honorary Member of the ICRC" (PDF). International Review of the Red Cross. 109: 210–211. April 1970. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Becknell, Arthur F. (1970). A History of the development of Dalcroze in the United States and its influence on the public school music program. Michigan: University of Michigan. pp. 152–162.

- ^ Thomas, Nathan (1995). Dalcroze Eurhythmics and Rhythm Training for Actors in American Universities. East Lansing: Michigan State University. Department of Theatre. p. 48.

- ^ Wieland Howe, Sondra (2014). Women Music Educators in the United States: A History. Lanham, MD: The Scarecrow Press. p. 246. ISBN 9780810888470.

- ^ a b c Mahood, Linda (2009). Feminism and Voluntary Action: Eglantyne Jebb and Save the Children, 1876–1928. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 173, 218, 257–258. ISBN 9780230525603.

- ^ George, Anne (9 February 2017), Suzanne Ferriere (d 1970), ICRC, IUCW, Save the Children Fund supporter, SCF/P/2/2 page 204, Cadbury Research Library, Cadbury Research Library, archived from the original on 15 July 2021, retrieved 30 June 2021

- ^ Banu, Roxana (3 March 2021). "The Role of the International Social Service in the History of Private International Law". International Social Service USA. Archived from the original on 12 August 2021. Retrieved 13 August 2021.

- ^ a b "Fonds: Union internationale de secours aux enfants – UISE – Union internationale de protection de l'enfance – UIPE – Série 35 / 123". Les Archives d'Etat de Genève. 737+and+ORIGINE=SERIE')&m=35&order=NATIVE('CDOCA,NUMSER')&type=SERIE&start=51 Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ' ^ "Fonds: Union internationale de secours aux enfants – UISE – Union internationale de protection de l'enfance – UIPE – Série 107 / 123". Les Archives d'Etat de Genève (in French). 737+and+ORIGINE=SERIE )&m=107&order=NATIVE('CDOCA,NUMSER')&type=SERIE&start=101 Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, Suzanne (September 1924). "Les Croix-Rouges de l'Amérique du Sud" (PDF). Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge (in French). 6 (71): 853–870. doi: 10.1017/S1026881200073402. S2CID 145657730. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Ferrière, Suzanne (January 1930). "Voyage en Syrie" (PDF). Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge (in French). 12 (133): 7–14. doi: 10.1017/S1026881200043543. S2CID 129036333. Archived (PDF) from the original on 30 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ a b c "Suzanne Ferrière". Journal de Genève. 63: 15. 17 March 1970. Archived from the original on 9 July 2021. Retrieved 7 October 2021.

- ^ "La délégation suisse à la S.D.N". Le Jura. 88 (109): 2. 13 September 1938. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Congres Internationaux". Journal et Feuille d'Avis du Valais et du Sion: 2. 6 September 1937. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "Die Delegation für die Völkerbundsversammlung". Neue Zürcher Nachrichten (in German). Vol. 145. 24 June 1939. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ "La Suisse à la Société des nations". La Liberté. 145: 6. 24 June 1939. Archived from the original on 3 September 2021. Retrieved 3 September 2021.

- ^ Rauh, Cornelia (2009). Schweizer Aluminium für Hitlers Krieg? Zur Geschichte der "Alusuisse" 1918–1950 (in German). Munich: Beck. ISBN 9783406522017.

- ^ Steinacher, Gerald (29 July 2017). "The Red Cross in Nazi Germany". OUPblog. Oxford University Press's Academic Insights for the Thinking World. Archived from the original on 28 April 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

- ^ Odier, Lucie (September 1943). "Mission en Afrique" (PDF). Revue Internationale de la Croix-Rouge et Bulletin international des Sociétés de la Croix-Rouge (in French). 25 (297): 730–743. doi: 10.1017/S1026881200015919. S2CID 145075925. Archived (PDF) from the original on 29 June 2021. Retrieved 30 June 2021.

External links

- Letter from Suzanne Ferrière to Carl Jacob Burckhardt – in French, dated 15 October 1938 – from Burckhardt's bequest at the library of the University of Basel

- Suzanne Ferrière in the Dodis data bank of the Diplomatic Documents of Switzerland

- Portrait photo of Ferrière from her later years in the ICRC Audiovisual Archives