| Special Province of Daerah Istimewa Surakarta Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Surakarta | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province-level special region of Indonesia | |||||||||||

| 1945–1946 | |||||||||||

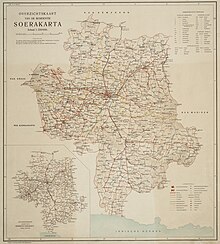

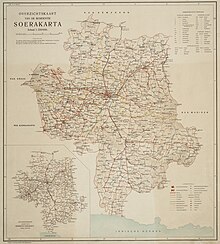

Location of the Special Province of Daerah Istimewa Surakarta | |||||||||||

| Capital | Surakarta | ||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||

| • Type | Devolved non-sovereign diarchical special region within a unitary republic | ||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

• 1945–1946 | Pakubuwono XII | ||||||||||

| Vice Governor | |||||||||||

• 1945–1946 | Mangkunegara VIII | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||||

• Established

[1] | 15 August 1945 | ||||||||||

• Dissolved and merged to Central Java

[2] | 16 June 1946 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Special Region of Surakarta was a de-facto provincial-level autonomous region of Indonesia that existed between August 1945 and July 1946. The establishment of this special autonomy status during this period was never established by a separate law based on Article 18 of the original Constitution, but only by a Presidential Determination Charter on 19 August 1945 and Law No. 1 Year 1945 on the Position of the Regional National Committee. [1]

Origin of the Special Region

The establishment of the Special Region was done by President Sukarno as a reward for the recognition of the kings of the Surakarta Sunanate and the Duchy of Mangkunegaran who declared their territory as part of the Republic of Indonesia on 19 August 1945. [3] [4]

Then on 1 September 1945, the Surakarta Royal Court and the Mangkunegaran Duchy sent an edict to President Sukarno regarding a statement from Susuhunan Pakubuwono XII and Adipati Mangkunegara VIII stating that the royal State of Surakarta Hadiningrat was a Special Region of the Republic of Indonesia, where the relationship between the State of Surakarta and the Central Government of the Republic of Indonesia was direct. On this basis, President Sukarno gave official recognition to Susuhunan Pakubuwono XII and Adipati Mangkunegara VIII by granting a charter of official position, each as the head of a special region. [1] [5] [6]

Four days later, on 5 September 1945, the Sultanate of Yogyakarta and the Duchy of Pakualaman issued a similar edict, which became the basis for the formation of the Special Region of Yogyakarta. [7] [8] [9] Making the Special Province of Surakarta's autonomy older than Yogyakarta's, have it not been abolished.

Administrative divisions

There has never been a regulation that mentions the position of the Surakarta Special Region on the subdivision of Indonesia. Whether at the provincial level (such as the Special Region of Yogyakarta) or at the Regency level (such as Kutai, Berau, and Bulongan). Thus, it cannot be clearly known what the position of Surakarta was. [10]

The Special Region of Surakarta includes:

- The Kasunanan territory consisting of: (a) Surakarta Regency (current Surakarta City (minus Banjarsari district, Kerten district, Jajar district and Karangasem district in Laweyan district, Mojosongo district in Jebres district) plus Sukoharjo Regency), (b) Klaten Regency (including Kotagede and Imogiri exclaves), (c) Boyolali Regency, (d) Sragen Regency;

- Mangkunegaran territory consisting of: (a) Karanganyar Regency (minus Colomadu and Gondangrejo districts), (b) Wonogiri Regency (including Ngawen exclave), [11] and (c) Mangkunegaran City Regency.

Governance

The government in Surakarta was divided into two stages during the period of August 1945 to July 1946. Each stage shows a significant difference.

DIS Government August 1945 – October 1945

During this period there was a dual government between:

- The Kooti Zimukyoku ( Japanese: 高地事務局, Hepburn: Kōchi-jimukyoku) ( Japanese government)

- Government of the Surakarta Regional Indonesian National Committee

- Surakarta Sunanate Government

- Praja Mangkunegaran Government

Each of these governments had its own powers and apparatus. The Kooti Zimukyoku government was a status quo government that continued the government for the Allied Forces as the victors of the Second World War. This government did not last long because it was soon captured by the Surakarta Regional KNI government. The Surakarta Regional KNI Government was a government formed by the people as a reaction to welcome Indonesian independence. This government formed a three-man Governing Council to exercise day-to-day executive power. [12]

The government of the Surakarta Sunanate was the government that continued the monarchy before the independence of Indonesia. It was led by the Pepatihdalem (Prime Minister) for and on behalf of His Majesty Pakubuwono XII. The government of Praja Mangkunegaran, which was a continuation of the monarchy before Indonesian independence, was led by the Patih for and on behalf of Mangkunegara VIII. With the existence of these various governments, there was an overlap of power and competition for the legitimacy of the people and the central government. [13] [14]

DIS Government October 1945 – July 1946

To overcome the chaos and overlapping governments in DIS, the Central Government sent the Governor of Central Java, Panji Soeroso, as the High Commissioner of Surakarta to mediate and to organise a new government. [15] Since then the DIS government has consisted of:

- High Commissioner of the Central Government

- KNI Surakarta Regional Working Committee

- Surakarta Regional Directorium

The High Commissioner of the Central Government was the representative of the Central government in Surakarta. This commissioner functions as the Head of the Special Region of Surakarta and oversees the work of the local legislature and the local executive. The KNI Surakarta Regional Working Committee was the local legislative body of the Surakarta Region. It was formed by and responsible to the Central Indonesian National Committee (KNIP) of the Surakarta Region. Members of the KNI Surakarta Regional Working Committee were elected by and from the members of the KNI Surakarta Region. The Surakarta Regional Directorium was the local executive body of the Surakarta Region. It consists of representatives from the KNI Surakarta, the Royal Government of Surakarta, and the Praja Mangkunegaran Government. The KNI of Surakarta Region has five representatives. The Royal Government of Surakarta had two representatives. The Mangkunegaran Royal Government had two representatives.

Politics

A Directorate Government consisting of Kasunanan, Mangkunegaran and KND elements did not work, because the Kasunanan and Mangkunegaran wanted to had individual interests, leading to further instability. [16] In its short span, the Special Region of Surakarta has not been free from various political upheavals. With the monarchical upheaval and the anti-swapraja (anti-monarchist) movement.

Monarchical upheaval

- The monarchical upheaval that occurred in the Surakarta Kingdom was the existence of the position of Patih. This position ruled for and on behalf of the susuhunan (ruler), causing Susuhan Pakubuwono XII to not freely move to accommodate the upheaval of the people. On 17 October 1945, the pepatihdalem (prime minister) of the Kesunanan and former BPUPK member, KRMH. Sasradiningrat V, was kidnapped by anti-swapraja mobs (he was later freed). This was followed by the removal of regents, many of whom were relatives of the king, and their replacement by pro-swapraja men. In March 1946, the new pepatihdalem, KRMT. Yudhanagara, was also kidnapped. And in April 1946, nine Kepatihan officials experienced the same thing. [17] The reoccurring incidents did not serve as a lesson to Surakarta by continuing to appoint a temporary acting patih to exercise the power of the Susuhunan. [18]

- The monarchical upheaval that occurred within Praja Mangkunegaran was the reluctance of the duke of Mangkunegaran to become Vice Governor of the Special Region to accompany the Susuhan Pakubuwono XII as Governor of the Special Region. Adipati Mangkunegara VIII, wanted Praja Mangkunegaran to be its own special region and not under Surakarta. This was because the area of the Praja was comparable in size to that of the Kingdom of Surakarta. In addition, the Praja was formed with the Treaty of Salatiga, which was almost the same weight as the Treaty of Giyanti.

- The upheaval of the monarchies of both the Kingdom of Surakarta and Praja Mangkunegaran was their defection by declaring to break away from Dutch rule and swearing its allegiance under the Indonesian government. Thus the monarchical rulers de-facto lost their territories and citizens.

- The police desertion of both the Kingdom of Surakarta and Praja Mangkunegaran was the defection of the monarchical police to join the police and armed forces of the Republic of Indonesia. Thus the monarchical rulers de-facto lost their government apparatus.

Anti-swapraja (anti-monarchist) agitation

- The leftist anti-monarchist upheaval was a revolutionary socialist-communist agitation to seize lands controlled by the monarchy.

- The anti-monarchist upheaval of the Opposition group was the upheaval of the opposition group not in the Indonesian cabinet government who also took a distance and a stance opposite to Sukarno-Hatta, making political adventures to counterbalance the centre of power in Yogyakarta by making Surakarta the "wild-west" of Yogyakarta.

Economy

Until now there has been no complete information about the economy of DIS between 1945–1946. However, it can be estimated that as usual, the economy after the war and in a state of revolution was in a deplorable state. This will be more pronounced when compared to the economy before the Second World War, especially during the reign of Pakubuwono X.

Socio-culture

Until now, there is no complete information about the socio-cultural condition of DIS between 1945–1946. The last condition before the Second World War put Surakarta Sunanate and Mangkunegaran Praja in a position to develop the agrarian industry, especially sugar cane and tobacco. This led to the growth of the labour class and eventually the socialist ideology, which in its more extreme form was communism, flourished. After Indonesian independence, supported by the decline of economic life and political turmoil, the working class moved to form a revolution.

Suspension and abolition

The freezing and abolition of the special region status was inseparable from the emergence of a social revolution in the form of an anti-swapraja movement in Surakarta, which took place simultaneously with the East Sumatran Social Revolution. Like the East Sumatran Social Revolution, the Surakarta anti-swapraja movement wanted to abolish the royal system on the grounds of anti-feudalism. [19] At the time of the establishment of the Special Region of Surakarta, Dr. Moewardi had a stronger influence than Pakubuwono XII, [20] who was considered to have no experience in managing matters of public interest, lacked the seriousness and courage to make decisions and did not understand the forces of revolution that were moving towards western democracy and popular sovereignty.[ citation needed] This was exacerbated by the disharmonious relationship between the Surakarta Sunanate and Mangkunegaran. [21]

On 17 October 1945, the Susuhunan pepatihdalem (Prime Minister), KRMH Sosrodiningrat was kidnapped and killed by the Swapraja movement. This was followed by the removal of regents in the Surakarta region who were relatives of the Susuhunan and Adipati Mangkunegara. In March 1946, the new pepatihdalem, KRMT Yudonagoro, was also kidnapped and killed by the Swapraja movement. In April 1946, nine Kepatihan officials also suffered the same fate. [18]

The anti-swapraja movement escalated into mass action. The Barisan Banteng (BB) unit, led by Muwardi, managed to take control of Surakarta while the Indonesian government did not suppress it because of General Sudirman's defence. In fact, General Sudirman also managed to urge the government to revoke Surakarta's special region status. On the city's seizure in January 1946, the Barisan Banteng kidnapped Pakubuwono XII, Kanjeng Ratu, and Soerjohamidjojo, demanding that Sunan be aligned with other popular leaders as "Bung" (meaning Comrade or Brother). Another motive was the seizure of agricultural lands controlled by the two monarchies to be divided to the peasants ( landreform) by the socialist movement of the anti-swapraja. In addition, they also demanded that he relinquish his political power and join the Republican Government. [20] [21] As a result of this incident, in May 1946, the Sjahrir Government arrested 12 PNI and BB leaders, including Dr Moewardi. Of course, BBRI did not accept the arrest. They then held a massive demonstration in Surakarta to demand the release of their leaders. The action was responded positively by the leader of the TRI (Tentara Republik Indonesia) General Soedirman by releasing the 12 people. [19]

The increasingly precarious conditions in Surakarta culminated on the 3 July Affair, when the first Prime Minister of Indonesia, Sutan Syahrir, was kidnapped by the republican opposition, Persatoean Perdjoangan (Union of Struggle), led by Major-General Sudarsono [22] and 14 civilian leaders, among them was Tan Malaka, of the Indonesian Communist Party. PM Syahrir was held in a rest house in Paras. President Sukarno was outraged by this uprising and ordered Surakarta Police to arrest the rebel leaders. On 1 July 1946, the 14 leaders were arrested and thrown into Wirogunan prison. However, on 2 July 1946, 3rd Division soldiers led by Major General Soedarsono stormed Wirogunan prison and released the 14 rebel leaders. [23] [24]

President Sukarno then ordered Lieutenant Colonel Soeharto, the army leader in Surakarta, to arrest Major General Soedarsono and the rebel leaders. However, Soeharto refused this order because he did not want to arrest his own leaders. He would only arrest the rebels if there was a direct order from the Indonesian military Chief of Staff, General Soedirman. President Sukarno was furious at this refusal and dubbed Lt. Col. Soeharto a stubborn officer ( Dutch: Koppig). [25] [24]

Following the kidnapping, a handful of opposition forces attempted to attack the presidential palace in Yogyakarta, but were foiled. [26] Major General Soedarsono and the rebel leaders were disarmed and arrested near the Presidential Palace in Yogyakarta by the presidential guard, after Lt. Col. Soeharto managed to persuade them to appear before President Sukarno. PM Syahrir was then released and Major General Soedarsono and the rebel leaders were sentenced to prison, although a few months later the rebels were pardoned by President Sukarno and released from prison. [25]

With the fear of spreading after the constant political upheavals and kidnappings, the Central Government of the Republic of Indonesia represented by Sultan Sjahrir, Amir Syarifuddin, and Sudarsono, with the Government of Special District Surakarta, represented by Pakubuwono XII, Mangkunegara VIII, KRMTH. Wuryaningrat, and KRMTH. Partohandoyo, opened up rounds of negotiations discussing the future of Surakarta. The meeting was held in the De Javasche Bank (DJB) Agentschap Soerakarta (now Bank Indonesia, Solo) building. [27] The government then issued Law No. 16/SD/1946 which decided that Surakarta became a temporary karesidenan ( residency) under a resident and was part of the territory of the Republic of Indonesia. And that both Pakubuwono XII and Mangkunegara VIII were no longer allowed to participate in politics or government and were merely a symbol. [2] [28]

On August 8, 1946, the Republic of Indonesia's central government issued a Government Regulation in Lieu of Law stating that the establishment of a Regional People's Representative Council in Surakarta was in charge of managing local region's matters, as a replacement of the KNI of Special Region of Surakarta, while its power remained in the hands of Resident appointed by the central government. [29] In less than a year, in June 1947, the Government of the Republic of Indonesia issued Law No. 16/47, which established the establishment of cities led by mayors, including Surakarta. [30] The power of Surakarta Hadiningrat Sunanate and Kadipaten Mangkunegaran became increasingly limited and wained as a result of the 1948 law governing the appointment of the Head of the former Special Region, who was always chosen from the descendants of the Royal family. Eventually, the Minister of Home Affairs, through a decree dated 3 March 1950, declared that the territories of the Sunanate and Mangkunegaran were administratively part of the province of Central Java. Both decrees ended Surakarta's special status [21] and merged the province to Central Java. [31]

Other reasons

There is an opinion[ who?] that at the beginning of his reign, Pakubuwono XII failed to take an important role and take advantage of the political situation of the Republic of Indonesia. Pakubuwono XII at that time was considered powerless in the face of anti-swapraja groups who aggressively maneuvered in politics and spread rumours that the Surakarta nobles were allies of the Dutch government, so that some people felt distrustful and rebelled against the rule of the Sunanate. [32] A belief that many people still hold to this day. [32] In the book series Sekitar Perang Kemerdekaan Indonesia, General Abdul Haris Nasution wrote that the kings of Surakarta defected and betrayed Indonesia during the Second Dutch Military Aggression in 1948–1949. The TNI had even prepared Colonel GPH Jatikusuma (the first Chief of Staff of the Indonesian Army), the son of Pakubuwono X, to be appointed as the new Susuhunan and Lt. Col. Suryo Sularso to be the new Mangkunegara. But some people and soldiers increasingly wanted to abolish the monarchy altogether. Finally Major Achmadi, the military ruler of Surakarta, was only given the task of directly liaising with the monarchical palaces of Surakarta. Both monarchs were asked to firmly side with the Republic. If they refused, action would be taken in accordance with the Non-Cooperation Instruction. [6]

In fact, during the National Revolution, Pakubuwono XII sided with the Indonesian government. He even obtained the military rank of titular lieutenant general. and in 1945–1948, he actively accompanied President Sukarno and Vice President Mohammad Hatta several times to visit various areas in Central and East Java, both in order to consolidate the government and to visit the front lines of battle. [33]

Re-establishment proposals

Attempt by Pakubuwono XII

In 1948, Law No. 22 article 18 paragraph 5 was issued to regulate regional government, stating that the Head of the Special Region was appointed by the President from the descendants of the ruling family from before the Republic of Indonesia, but in the discussion of the Central Indonesian National Committee session, several words in article 18 were changed. The changes became clearer when on 24 November 1951, Pakubuwono XII received a letter sent by the Soekiman Cabinet (Surat No. 66/5/38) stating that the new draft government regulation was not in accordance with Law No. 22 article 15. Law No. 22 article 15 and that he was summoned to clarify the status. [34]

In a last attempt, Pakubuwono XII had tried to restore the status of Surakarta Special Region. On 15 January 1952, Pakubuwono XII gave a lengthy explanation about Surakarta Special Region to the Cabinet of Indonesia in Jakarta, on this occasion he explained that the Swapraja Government was unable to overcome the turmoil and undermining accompanied by armed threats, while the Swapraja Government itself had no means of power. However, these efforts faltered because they never reached a consensus, on the basis of trivial issues can complicate matters. [34] [35] [36]

Recent developments in the Reformation era

Along with the reopening of the spirit of regional autonomy and with the granting of Special Autonomy to Papua (2001), West Papua (2008), Aceh (2001 and 2006), DKI Jakarta (1999 and 2007) followed by Central Papua, South Papua, Mountainous Papua and Southwest Papua (2022) and the affirmation of the privileges of Aceh (1999 and 2006) and Yogyakarta (2012), there is a discourse to revive the Special Region of Surakarta as part of the Republic of Indonesia. One of the steps that will be taken is to conduct a judicial review to the Constitutional Court of the Law on the State of the Republic of Indonesia Number 10 of 1950.

On 14 December 2010, a group of people held a demonstration and a joint prayer, known as 'Ritual Wilujengan', at the border of Yogyakarta Province, near the south side of Prambanan Temple area. The protesters demanded the government's promise to give them as a special region, in accordance with UUD 45 article 18 and that they would go to the Constitutional Court if not fulfilled. Attended by those who claimed to be delegates from the community in across the greater Solo area, the demonstrators wore traditional Javanese clothes in Solo style with yellow Kasunanan necklaces. They also carried red and white banners with historical facts. [37] [38]

On 26 June 2013, a lawsuit was filed to the Constitutional Court by two purported members of the royal family of Surakarta. Stating that they want to establish a special autonomous region for their territory on behalf of the Kasunanan. The petitioners contended that the Special Region of Surakarta held historical and constitutional significance, possessing its own government and culture. They argued that the region's dissolution and subsequent integration into Central Java Province contravened the provisions outlined in the 1945 Constitution. They challenge a 1950 law that abolished the residency system and merged Surakarta with other regions into Central Java province. [39] The lawsuit garnered media attention, which prompted a reaction from then elected governor of Central Java, Ganjar Pranowo and his provincial government. Central Java provincial council gave out a statement of disagreement with the demand for Surakarta Special Region. While Ganjar stated that he would respect whatever decision the Constitutional Court makes regarding the lawsuit and that the matter of Surakarta Special Region is up to the president and the parliament, while the governor and the provincial council can only give recommendations after a thorough study. [40] Though, he questioned the rationale behind the demand for Surakarta Special Region, and whether it would improve governance and public service, as it could create unrest among the people. [40] [41]

On 27 March 2014, the Constitutional Court ultimately dismissed the petition challenging the validity of Law No. 10 of 1950 concerning the Establishment of Central Java Province. The court based its ruling on the lack of legal standing of the petitioners in requesting the legal status of Surakarta Special Region. Moreover, the court raised doubts regarding the legitimacy of one of the petitioners, who claimed to be the son of Susuhunan Pakubuwono XII, the final ruler of the Surakarta Palace. [42] The Minister of Youth and Sports Affairs, Roy Suryo, who is a relative of the Yogyakartan Keraton supports the decision of the Constitutional Court and, without explaining further, stated that there is a difference between the Surakarta Keraton and the Yogyakarta Keraton during the independence era. A member of the Surakarta Palace's Traditional Council, Satriyo Hadinagoro, criticizes the Constitutional Court's ruling and called it “funny and unreasonable” and said that his side would file another lawsuit. He also questioned Roy Suryo’s involvement in the palace conflict. [43] [44]

Reference

- ^ a b c "Pangeran Surakarta Ajukan Piagam Soekarno Jadi Bukti Keistimewaan". Constitutional Court of Indonesia. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ a b "UU No. 16 Tahun 1946 tentang Pernyataan Keadaan Bahaya di Seluruh Indonesia [JDIH BPK RI]". bpk.go.id. Archived (pdf) from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ Furthermore, on 19 August 1945 at the PPKI meeting it was decided that the territory of the Republic of Indonesia was divided into nine provinces and two special regions, namely West Java, Central Java, East Java, Lesser Sunda, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku, Special Region of Surakarta, Special Region of Yogyakarta. This opinion contradicts the PPKI Decision as contained in the book Risalah Sidang BPUPKI dan PPKI published by the state secretariat, both editions II (1993) and III (1995).

- ^ Risalah Sidang BPUPKI dan PPKI (in Indonesian) (3 ed.). Jakarta: Secretary of State of Indonesia (SETNEG). 1995. ISBN 979-8300-00-9.

- ^ as the Head of the Special Region of Surakarta, which was equivalent to the position of Governor and directly under the Central Government. This opinion contradicts Law 22/1948 on regional government and the historical facts in which R.P. Suroso was placed as the Indonesian High Commissioner for Kesunanan and Mangkunegaran. See A.H. Nasution's book Sekitar Perang Kemerdekaan Indonesia and Sudarisman Purwokusumo's Special Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta.

- ^ a b Nasution, Abdul Haris (1996). Sekitar Perang Kemerdekaan Indonesia: perang gerilya semesta ii (in Indonesian). Vol. 10. Bandung: Bandung: Disjarah Angkatan Darat dan Penerbit Angkasa. p. 8. ISBN 979-547-280-1.

- ^ "Amanat 5 September 1945 - Wikisource bahasa Indonesia". id.wikisource.org (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ Mahany, Andry Trisandy (2022-09-17). "Amanat 5 September 1945". Special Province of Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta Government. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ Adryamarthanino, Verelladevanka (2021-11-03). Nailufar, Nibras Nada (ed.). "Amanat 5 September 1945: Bergabungnya Yogyakarta dengan NKRI Halaman all". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ The position of special regions at the level of provinces or at the level of regencies, or at the level of villages only existed in 1948 through Law 22/1948 (UU 22/1948), even though DIS had been frozen/dissolved smoothly in 1946 two years before the law was passed.

- ^ Since 1957, it has been the territory of DIY

- ^ Samroni, Imam (2010). Daerah Istimewa Surakarta. Pura Pustaka Yogyakarta.

- ^ "Indonesian Traditional States part 1". www.worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ Negoro, Suryo. "Sri Mangkoenagoro IX". Joglosemar Online. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ Evita, Andi Lili (2017). Gubernur Pertama Di Indonesia. Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. ISBN 978-602-1289-72-3.

- ^ Kartodirdjo, Sartono (1993). Pengantar sejarah Indonesia baru : sejarah pergerakan nasional dari kolonialisme sampai nasionalisme (in Indonesian) (3rd ed.). Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. pp. 108–109. ISBN 979-403-767-2.

- ^ Daerah Istimewa Surakarta - Tuduhan Pro Belanda dan Kesetiaannya kepada Republik Indonesia, retrieved 2023-06-28

- ^ a b Joko Darmawan (2017). Mengenal Budaya Nasional "Trah Raja-raja Mataram di Tanah Jawa". Yogyakarta: Deepublish. ISBN 9786024532413.

- ^ a b Johari, Hendi (2019-05-17). "Di Bawah Simbol Banteng". Historia - Majalah Sejarah Populer Pertama di Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^

a

b

tirto

.id /penculikan-pakubuwono-xii-dan-dihapusnya-daerah-istimewa-surakarta-f8aC - ^

a

b

c Sutiyah, Sutiyah (2017-09-19).

"KEHIDUPAN POLITIK DI KOTA SURAKARTA DAN YOGYAKARTA MENJELANG PEMILIHAN UMUM 1955". Paramita: Historical Studies Journal (in Indonesian). 27 (2). Universitas Negeri Semarang: 198.

doi:

10.15294/paramita.v27i2.11164 (inactive 31 January 2024).

ISSN

2407-5825.

{{ cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 ( link) - ^ "Sejarah Peristiwa 3 Juli 1946, Kudeta Pertama di Indonesia". tirto.id (in Indonesian). 3 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- ^ Matanasi, Petrik (29 December 2020). "Penculikan Pakubuwono XII dan Dihapusnya Daerah Istimewa Surakarta". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ a b "Kisah Penculikan Sjahrir". Historia - Majalah Sejarah Populer Pertama di Indonesia (in Indonesian). 2019-11-04. Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ^ a b Soeharto; Dwipayana, G.; Hadimadja, Ramadhan Karta (1991). Soeharto, My Thoughts, Words, and Deeds: An Autobiography. Citra Lamtoro Gung Persada. ISBN 978-979-8085-01-7.

- ^ Prasadana, Muhammad Anggie Farizqi; Gunawan, Hendri (2019-06-17). "Keruntuhan Birokrasi Tradisional di Kasunanan Surakarta". Handep: Jurnal Sejarah Dan Budaya (in Indonesian). 2 (2). Balai Pelestarian Budaya Kalimantan Barat: 196. doi: 10.33652/handep.v2i2.36. ISSN 2684-7256. S2CID 198039293.

- ^ "Gedung Lawas Bank Indonesia Solo, Pernah Dipakai PM Sutan Sjahrir di Era Kemerdekaan Indonesia". Dinas Komunikasi, Informatika, Statistik dan Persandian Kota Surakarta. 18 February 2023.

- ^ "Keraton Surakarta Tuntut Status Istimewa". Constitutional Court of Indonesia. Archived from the original on 2020-06-19. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- ^ "Selayang Pandang Kota Surakarta". DPRD Kota Surakarta.

- ^ "UU No. 16 Tahun 1947 tentang Pembentukan Haminte-Kota Surakarta [JDIH BPK RI]". peraturan.bpk.go.id. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- ^ "Profil Jawa Tengah". jawatengah.go.id. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006. Retrieved 20 June 2023 – via Archive.org.

- ^ a b Putri Musaparsih, Cahya (2005). "Strategi Komite Nasional Indonesia Daerah Surakarta (KNIDS) dalam mengambil alih Swapraja, 1945-1946" (PDF). Skripsi. Jurusan Ilmu Sejarah, Fakultas Sastra dan Seni Rupa, Universitas Sebelas Maret Surakarta.

- ^ Setiadi, Bram; Trihandayani, D.S.; Hadi, Qomarul (2001). Raja di Alam Republik: Keraton Kesunanan Surakarta dan Paku Buwono XII. Jakarta: Bina Rena Pariwara.

- ^ a b Yosodipura, K. R. M. H. (1994). Karaton Surakarta Hadiningrat Bangunan Budaya Jawa sebagai Tuntunan Hidup. Pembangunan Budi Pakarti Kejawen.

- ^ Media, Kompas Cyber (2023-02-05). "Sri Susuhunan Pakubuwono XII, Pernah Diculik Barisan Banteng Halaman all". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-07-10.

-

^ Yuniyati, Winahyu Adha (2014).

"Kedudukan Selir Pakubuwana XII Di Keraton Surakarta (1944 – 2004)" (in Indonesian).

{{ cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=( help) - ^ "Masyarakat Surakarta Tuntut Dikembalikannya Daerah Istimewa Surakarta". detiknews (in Indonesian). 14 December 2010. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ Pradana, Rifky (2010-12-15). "Daerah Istimewa Surakarta, Cemburu Jogja?". KOMPASIANA (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ "Tuntut Daerah Istimewa, Trah Keraton Surakarta Ingin Lepas dari Jateng". detiknews (in Indonesian). 26 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ a b Adhi Nugroho, Wisnu (7 July 2013). "Ganjar Tunggu Putuskan MK Terkait Pembentukan Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Surakarta". Antara News (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ Parwito (8 July 2013). "Ganjar nilai wacana pemekaran Surakarta berasal dari keraton". merdeka.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ Susilo, Joko (2014-03-27). "MK tolak gugatan ahli waris Keraton Surakarta". Antara News. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ Fadjri, Raihul (2014-03-31). "Menteri Roy: Status Istimewa Surakarta Ditolak karena Sejarah". Tempo. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ Sunaryo, Arie (2014-03-30). "Roy Suryo dukung MK tolak Daerah Istimewa Surakarta". merdeka.com. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

See also

- Provinces of Indonesia

- Central Java

- History of Surakarta

- Surakarta Sunanate

- Special Region of Yogyakarta

| Special Province of Daerah Istimewa Surakarta Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Surakarta | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province-level special region of Indonesia | |||||||||||

| 1945–1946 | |||||||||||

Location of the Special Province of Daerah Istimewa Surakarta | |||||||||||

| Capital | Surakarta | ||||||||||

| Government | |||||||||||

| • Type | Devolved non-sovereign diarchical special region within a unitary republic | ||||||||||

| Governor | |||||||||||

• 1945–1946 | Pakubuwono XII | ||||||||||

| Vice Governor | |||||||||||

• 1945–1946 | Mangkunegara VIII | ||||||||||

| Historical era | Cold War | ||||||||||

• Established

[1] | 15 August 1945 | ||||||||||

• Dissolved and merged to Central Java

[2] | 16 June 1946 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

The Special Region of Surakarta was a de-facto provincial-level autonomous region of Indonesia that existed between August 1945 and July 1946. The establishment of this special autonomy status during this period was never established by a separate law based on Article 18 of the original Constitution, but only by a Presidential Determination Charter on 19 August 1945 and Law No. 1 Year 1945 on the Position of the Regional National Committee. [1]

Origin of the Special Region

The establishment of the Special Region was done by President Sukarno as a reward for the recognition of the kings of the Surakarta Sunanate and the Duchy of Mangkunegaran who declared their territory as part of the Republic of Indonesia on 19 August 1945. [3] [4]

Then on 1 September 1945, the Surakarta Royal Court and the Mangkunegaran Duchy sent an edict to President Sukarno regarding a statement from Susuhunan Pakubuwono XII and Adipati Mangkunegara VIII stating that the royal State of Surakarta Hadiningrat was a Special Region of the Republic of Indonesia, where the relationship between the State of Surakarta and the Central Government of the Republic of Indonesia was direct. On this basis, President Sukarno gave official recognition to Susuhunan Pakubuwono XII and Adipati Mangkunegara VIII by granting a charter of official position, each as the head of a special region. [1] [5] [6]

Four days later, on 5 September 1945, the Sultanate of Yogyakarta and the Duchy of Pakualaman issued a similar edict, which became the basis for the formation of the Special Region of Yogyakarta. [7] [8] [9] Making the Special Province of Surakarta's autonomy older than Yogyakarta's, have it not been abolished.

Administrative divisions

There has never been a regulation that mentions the position of the Surakarta Special Region on the subdivision of Indonesia. Whether at the provincial level (such as the Special Region of Yogyakarta) or at the Regency level (such as Kutai, Berau, and Bulongan). Thus, it cannot be clearly known what the position of Surakarta was. [10]

The Special Region of Surakarta includes:

- The Kasunanan territory consisting of: (a) Surakarta Regency (current Surakarta City (minus Banjarsari district, Kerten district, Jajar district and Karangasem district in Laweyan district, Mojosongo district in Jebres district) plus Sukoharjo Regency), (b) Klaten Regency (including Kotagede and Imogiri exclaves), (c) Boyolali Regency, (d) Sragen Regency;

- Mangkunegaran territory consisting of: (a) Karanganyar Regency (minus Colomadu and Gondangrejo districts), (b) Wonogiri Regency (including Ngawen exclave), [11] and (c) Mangkunegaran City Regency.

Governance

The government in Surakarta was divided into two stages during the period of August 1945 to July 1946. Each stage shows a significant difference.

DIS Government August 1945 – October 1945

During this period there was a dual government between:

- The Kooti Zimukyoku ( Japanese: 高地事務局, Hepburn: Kōchi-jimukyoku) ( Japanese government)

- Government of the Surakarta Regional Indonesian National Committee

- Surakarta Sunanate Government

- Praja Mangkunegaran Government

Each of these governments had its own powers and apparatus. The Kooti Zimukyoku government was a status quo government that continued the government for the Allied Forces as the victors of the Second World War. This government did not last long because it was soon captured by the Surakarta Regional KNI government. The Surakarta Regional KNI Government was a government formed by the people as a reaction to welcome Indonesian independence. This government formed a three-man Governing Council to exercise day-to-day executive power. [12]

The government of the Surakarta Sunanate was the government that continued the monarchy before the independence of Indonesia. It was led by the Pepatihdalem (Prime Minister) for and on behalf of His Majesty Pakubuwono XII. The government of Praja Mangkunegaran, which was a continuation of the monarchy before Indonesian independence, was led by the Patih for and on behalf of Mangkunegara VIII. With the existence of these various governments, there was an overlap of power and competition for the legitimacy of the people and the central government. [13] [14]

DIS Government October 1945 – July 1946

To overcome the chaos and overlapping governments in DIS, the Central Government sent the Governor of Central Java, Panji Soeroso, as the High Commissioner of Surakarta to mediate and to organise a new government. [15] Since then the DIS government has consisted of:

- High Commissioner of the Central Government

- KNI Surakarta Regional Working Committee

- Surakarta Regional Directorium

The High Commissioner of the Central Government was the representative of the Central government in Surakarta. This commissioner functions as the Head of the Special Region of Surakarta and oversees the work of the local legislature and the local executive. The KNI Surakarta Regional Working Committee was the local legislative body of the Surakarta Region. It was formed by and responsible to the Central Indonesian National Committee (KNIP) of the Surakarta Region. Members of the KNI Surakarta Regional Working Committee were elected by and from the members of the KNI Surakarta Region. The Surakarta Regional Directorium was the local executive body of the Surakarta Region. It consists of representatives from the KNI Surakarta, the Royal Government of Surakarta, and the Praja Mangkunegaran Government. The KNI of Surakarta Region has five representatives. The Royal Government of Surakarta had two representatives. The Mangkunegaran Royal Government had two representatives.

Politics

A Directorate Government consisting of Kasunanan, Mangkunegaran and KND elements did not work, because the Kasunanan and Mangkunegaran wanted to had individual interests, leading to further instability. [16] In its short span, the Special Region of Surakarta has not been free from various political upheavals. With the monarchical upheaval and the anti-swapraja (anti-monarchist) movement.

Monarchical upheaval

- The monarchical upheaval that occurred in the Surakarta Kingdom was the existence of the position of Patih. This position ruled for and on behalf of the susuhunan (ruler), causing Susuhan Pakubuwono XII to not freely move to accommodate the upheaval of the people. On 17 October 1945, the pepatihdalem (prime minister) of the Kesunanan and former BPUPK member, KRMH. Sasradiningrat V, was kidnapped by anti-swapraja mobs (he was later freed). This was followed by the removal of regents, many of whom were relatives of the king, and their replacement by pro-swapraja men. In March 1946, the new pepatihdalem, KRMT. Yudhanagara, was also kidnapped. And in April 1946, nine Kepatihan officials experienced the same thing. [17] The reoccurring incidents did not serve as a lesson to Surakarta by continuing to appoint a temporary acting patih to exercise the power of the Susuhunan. [18]

- The monarchical upheaval that occurred within Praja Mangkunegaran was the reluctance of the duke of Mangkunegaran to become Vice Governor of the Special Region to accompany the Susuhan Pakubuwono XII as Governor of the Special Region. Adipati Mangkunegara VIII, wanted Praja Mangkunegaran to be its own special region and not under Surakarta. This was because the area of the Praja was comparable in size to that of the Kingdom of Surakarta. In addition, the Praja was formed with the Treaty of Salatiga, which was almost the same weight as the Treaty of Giyanti.

- The upheaval of the monarchies of both the Kingdom of Surakarta and Praja Mangkunegaran was their defection by declaring to break away from Dutch rule and swearing its allegiance under the Indonesian government. Thus the monarchical rulers de-facto lost their territories and citizens.

- The police desertion of both the Kingdom of Surakarta and Praja Mangkunegaran was the defection of the monarchical police to join the police and armed forces of the Republic of Indonesia. Thus the monarchical rulers de-facto lost their government apparatus.

Anti-swapraja (anti-monarchist) agitation

- The leftist anti-monarchist upheaval was a revolutionary socialist-communist agitation to seize lands controlled by the monarchy.

- The anti-monarchist upheaval of the Opposition group was the upheaval of the opposition group not in the Indonesian cabinet government who also took a distance and a stance opposite to Sukarno-Hatta, making political adventures to counterbalance the centre of power in Yogyakarta by making Surakarta the "wild-west" of Yogyakarta.

Economy

Until now there has been no complete information about the economy of DIS between 1945–1946. However, it can be estimated that as usual, the economy after the war and in a state of revolution was in a deplorable state. This will be more pronounced when compared to the economy before the Second World War, especially during the reign of Pakubuwono X.

Socio-culture

Until now, there is no complete information about the socio-cultural condition of DIS between 1945–1946. The last condition before the Second World War put Surakarta Sunanate and Mangkunegaran Praja in a position to develop the agrarian industry, especially sugar cane and tobacco. This led to the growth of the labour class and eventually the socialist ideology, which in its more extreme form was communism, flourished. After Indonesian independence, supported by the decline of economic life and political turmoil, the working class moved to form a revolution.

Suspension and abolition

The freezing and abolition of the special region status was inseparable from the emergence of a social revolution in the form of an anti-swapraja movement in Surakarta, which took place simultaneously with the East Sumatran Social Revolution. Like the East Sumatran Social Revolution, the Surakarta anti-swapraja movement wanted to abolish the royal system on the grounds of anti-feudalism. [19] At the time of the establishment of the Special Region of Surakarta, Dr. Moewardi had a stronger influence than Pakubuwono XII, [20] who was considered to have no experience in managing matters of public interest, lacked the seriousness and courage to make decisions and did not understand the forces of revolution that were moving towards western democracy and popular sovereignty.[ citation needed] This was exacerbated by the disharmonious relationship between the Surakarta Sunanate and Mangkunegaran. [21]

On 17 October 1945, the Susuhunan pepatihdalem (Prime Minister), KRMH Sosrodiningrat was kidnapped and killed by the Swapraja movement. This was followed by the removal of regents in the Surakarta region who were relatives of the Susuhunan and Adipati Mangkunegara. In March 1946, the new pepatihdalem, KRMT Yudonagoro, was also kidnapped and killed by the Swapraja movement. In April 1946, nine Kepatihan officials also suffered the same fate. [18]

The anti-swapraja movement escalated into mass action. The Barisan Banteng (BB) unit, led by Muwardi, managed to take control of Surakarta while the Indonesian government did not suppress it because of General Sudirman's defence. In fact, General Sudirman also managed to urge the government to revoke Surakarta's special region status. On the city's seizure in January 1946, the Barisan Banteng kidnapped Pakubuwono XII, Kanjeng Ratu, and Soerjohamidjojo, demanding that Sunan be aligned with other popular leaders as "Bung" (meaning Comrade or Brother). Another motive was the seizure of agricultural lands controlled by the two monarchies to be divided to the peasants ( landreform) by the socialist movement of the anti-swapraja. In addition, they also demanded that he relinquish his political power and join the Republican Government. [20] [21] As a result of this incident, in May 1946, the Sjahrir Government arrested 12 PNI and BB leaders, including Dr Moewardi. Of course, BBRI did not accept the arrest. They then held a massive demonstration in Surakarta to demand the release of their leaders. The action was responded positively by the leader of the TRI (Tentara Republik Indonesia) General Soedirman by releasing the 12 people. [19]

The increasingly precarious conditions in Surakarta culminated on the 3 July Affair, when the first Prime Minister of Indonesia, Sutan Syahrir, was kidnapped by the republican opposition, Persatoean Perdjoangan (Union of Struggle), led by Major-General Sudarsono [22] and 14 civilian leaders, among them was Tan Malaka, of the Indonesian Communist Party. PM Syahrir was held in a rest house in Paras. President Sukarno was outraged by this uprising and ordered Surakarta Police to arrest the rebel leaders. On 1 July 1946, the 14 leaders were arrested and thrown into Wirogunan prison. However, on 2 July 1946, 3rd Division soldiers led by Major General Soedarsono stormed Wirogunan prison and released the 14 rebel leaders. [23] [24]

President Sukarno then ordered Lieutenant Colonel Soeharto, the army leader in Surakarta, to arrest Major General Soedarsono and the rebel leaders. However, Soeharto refused this order because he did not want to arrest his own leaders. He would only arrest the rebels if there was a direct order from the Indonesian military Chief of Staff, General Soedirman. President Sukarno was furious at this refusal and dubbed Lt. Col. Soeharto a stubborn officer ( Dutch: Koppig). [25] [24]

Following the kidnapping, a handful of opposition forces attempted to attack the presidential palace in Yogyakarta, but were foiled. [26] Major General Soedarsono and the rebel leaders were disarmed and arrested near the Presidential Palace in Yogyakarta by the presidential guard, after Lt. Col. Soeharto managed to persuade them to appear before President Sukarno. PM Syahrir was then released and Major General Soedarsono and the rebel leaders were sentenced to prison, although a few months later the rebels were pardoned by President Sukarno and released from prison. [25]

With the fear of spreading after the constant political upheavals and kidnappings, the Central Government of the Republic of Indonesia represented by Sultan Sjahrir, Amir Syarifuddin, and Sudarsono, with the Government of Special District Surakarta, represented by Pakubuwono XII, Mangkunegara VIII, KRMTH. Wuryaningrat, and KRMTH. Partohandoyo, opened up rounds of negotiations discussing the future of Surakarta. The meeting was held in the De Javasche Bank (DJB) Agentschap Soerakarta (now Bank Indonesia, Solo) building. [27] The government then issued Law No. 16/SD/1946 which decided that Surakarta became a temporary karesidenan ( residency) under a resident and was part of the territory of the Republic of Indonesia. And that both Pakubuwono XII and Mangkunegara VIII were no longer allowed to participate in politics or government and were merely a symbol. [2] [28]

On August 8, 1946, the Republic of Indonesia's central government issued a Government Regulation in Lieu of Law stating that the establishment of a Regional People's Representative Council in Surakarta was in charge of managing local region's matters, as a replacement of the KNI of Special Region of Surakarta, while its power remained in the hands of Resident appointed by the central government. [29] In less than a year, in June 1947, the Government of the Republic of Indonesia issued Law No. 16/47, which established the establishment of cities led by mayors, including Surakarta. [30] The power of Surakarta Hadiningrat Sunanate and Kadipaten Mangkunegaran became increasingly limited and wained as a result of the 1948 law governing the appointment of the Head of the former Special Region, who was always chosen from the descendants of the Royal family. Eventually, the Minister of Home Affairs, through a decree dated 3 March 1950, declared that the territories of the Sunanate and Mangkunegaran were administratively part of the province of Central Java. Both decrees ended Surakarta's special status [21] and merged the province to Central Java. [31]

Other reasons

There is an opinion[ who?] that at the beginning of his reign, Pakubuwono XII failed to take an important role and take advantage of the political situation of the Republic of Indonesia. Pakubuwono XII at that time was considered powerless in the face of anti-swapraja groups who aggressively maneuvered in politics and spread rumours that the Surakarta nobles were allies of the Dutch government, so that some people felt distrustful and rebelled against the rule of the Sunanate. [32] A belief that many people still hold to this day. [32] In the book series Sekitar Perang Kemerdekaan Indonesia, General Abdul Haris Nasution wrote that the kings of Surakarta defected and betrayed Indonesia during the Second Dutch Military Aggression in 1948–1949. The TNI had even prepared Colonel GPH Jatikusuma (the first Chief of Staff of the Indonesian Army), the son of Pakubuwono X, to be appointed as the new Susuhunan and Lt. Col. Suryo Sularso to be the new Mangkunegara. But some people and soldiers increasingly wanted to abolish the monarchy altogether. Finally Major Achmadi, the military ruler of Surakarta, was only given the task of directly liaising with the monarchical palaces of Surakarta. Both monarchs were asked to firmly side with the Republic. If they refused, action would be taken in accordance with the Non-Cooperation Instruction. [6]

In fact, during the National Revolution, Pakubuwono XII sided with the Indonesian government. He even obtained the military rank of titular lieutenant general. and in 1945–1948, he actively accompanied President Sukarno and Vice President Mohammad Hatta several times to visit various areas in Central and East Java, both in order to consolidate the government and to visit the front lines of battle. [33]

Re-establishment proposals

Attempt by Pakubuwono XII

In 1948, Law No. 22 article 18 paragraph 5 was issued to regulate regional government, stating that the Head of the Special Region was appointed by the President from the descendants of the ruling family from before the Republic of Indonesia, but in the discussion of the Central Indonesian National Committee session, several words in article 18 were changed. The changes became clearer when on 24 November 1951, Pakubuwono XII received a letter sent by the Soekiman Cabinet (Surat No. 66/5/38) stating that the new draft government regulation was not in accordance with Law No. 22 article 15. Law No. 22 article 15 and that he was summoned to clarify the status. [34]

In a last attempt, Pakubuwono XII had tried to restore the status of Surakarta Special Region. On 15 January 1952, Pakubuwono XII gave a lengthy explanation about Surakarta Special Region to the Cabinet of Indonesia in Jakarta, on this occasion he explained that the Swapraja Government was unable to overcome the turmoil and undermining accompanied by armed threats, while the Swapraja Government itself had no means of power. However, these efforts faltered because they never reached a consensus, on the basis of trivial issues can complicate matters. [34] [35] [36]

Recent developments in the Reformation era

Along with the reopening of the spirit of regional autonomy and with the granting of Special Autonomy to Papua (2001), West Papua (2008), Aceh (2001 and 2006), DKI Jakarta (1999 and 2007) followed by Central Papua, South Papua, Mountainous Papua and Southwest Papua (2022) and the affirmation of the privileges of Aceh (1999 and 2006) and Yogyakarta (2012), there is a discourse to revive the Special Region of Surakarta as part of the Republic of Indonesia. One of the steps that will be taken is to conduct a judicial review to the Constitutional Court of the Law on the State of the Republic of Indonesia Number 10 of 1950.

On 14 December 2010, a group of people held a demonstration and a joint prayer, known as 'Ritual Wilujengan', at the border of Yogyakarta Province, near the south side of Prambanan Temple area. The protesters demanded the government's promise to give them as a special region, in accordance with UUD 45 article 18 and that they would go to the Constitutional Court if not fulfilled. Attended by those who claimed to be delegates from the community in across the greater Solo area, the demonstrators wore traditional Javanese clothes in Solo style with yellow Kasunanan necklaces. They also carried red and white banners with historical facts. [37] [38]

On 26 June 2013, a lawsuit was filed to the Constitutional Court by two purported members of the royal family of Surakarta. Stating that they want to establish a special autonomous region for their territory on behalf of the Kasunanan. The petitioners contended that the Special Region of Surakarta held historical and constitutional significance, possessing its own government and culture. They argued that the region's dissolution and subsequent integration into Central Java Province contravened the provisions outlined in the 1945 Constitution. They challenge a 1950 law that abolished the residency system and merged Surakarta with other regions into Central Java province. [39] The lawsuit garnered media attention, which prompted a reaction from then elected governor of Central Java, Ganjar Pranowo and his provincial government. Central Java provincial council gave out a statement of disagreement with the demand for Surakarta Special Region. While Ganjar stated that he would respect whatever decision the Constitutional Court makes regarding the lawsuit and that the matter of Surakarta Special Region is up to the president and the parliament, while the governor and the provincial council can only give recommendations after a thorough study. [40] Though, he questioned the rationale behind the demand for Surakarta Special Region, and whether it would improve governance and public service, as it could create unrest among the people. [40] [41]

On 27 March 2014, the Constitutional Court ultimately dismissed the petition challenging the validity of Law No. 10 of 1950 concerning the Establishment of Central Java Province. The court based its ruling on the lack of legal standing of the petitioners in requesting the legal status of Surakarta Special Region. Moreover, the court raised doubts regarding the legitimacy of one of the petitioners, who claimed to be the son of Susuhunan Pakubuwono XII, the final ruler of the Surakarta Palace. [42] The Minister of Youth and Sports Affairs, Roy Suryo, who is a relative of the Yogyakartan Keraton supports the decision of the Constitutional Court and, without explaining further, stated that there is a difference between the Surakarta Keraton and the Yogyakarta Keraton during the independence era. A member of the Surakarta Palace's Traditional Council, Satriyo Hadinagoro, criticizes the Constitutional Court's ruling and called it “funny and unreasonable” and said that his side would file another lawsuit. He also questioned Roy Suryo’s involvement in the palace conflict. [43] [44]

Reference

- ^ a b c "Pangeran Surakarta Ajukan Piagam Soekarno Jadi Bukti Keistimewaan". Constitutional Court of Indonesia. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ a b "UU No. 16 Tahun 1946 tentang Pernyataan Keadaan Bahaya di Seluruh Indonesia [JDIH BPK RI]". bpk.go.id. Archived (pdf) from the original on 23 September 2020. Retrieved 2023-06-20.

- ^ Furthermore, on 19 August 1945 at the PPKI meeting it was decided that the territory of the Republic of Indonesia was divided into nine provinces and two special regions, namely West Java, Central Java, East Java, Lesser Sunda, Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku, Special Region of Surakarta, Special Region of Yogyakarta. This opinion contradicts the PPKI Decision as contained in the book Risalah Sidang BPUPKI dan PPKI published by the state secretariat, both editions II (1993) and III (1995).

- ^ Risalah Sidang BPUPKI dan PPKI (in Indonesian) (3 ed.). Jakarta: Secretary of State of Indonesia (SETNEG). 1995. ISBN 979-8300-00-9.

- ^ as the Head of the Special Region of Surakarta, which was equivalent to the position of Governor and directly under the Central Government. This opinion contradicts Law 22/1948 on regional government and the historical facts in which R.P. Suroso was placed as the Indonesian High Commissioner for Kesunanan and Mangkunegaran. See A.H. Nasution's book Sekitar Perang Kemerdekaan Indonesia and Sudarisman Purwokusumo's Special Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta.

- ^ a b Nasution, Abdul Haris (1996). Sekitar Perang Kemerdekaan Indonesia: perang gerilya semesta ii (in Indonesian). Vol. 10. Bandung: Bandung: Disjarah Angkatan Darat dan Penerbit Angkasa. p. 8. ISBN 979-547-280-1.

- ^ "Amanat 5 September 1945 - Wikisource bahasa Indonesia". id.wikisource.org (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ Mahany, Andry Trisandy (2022-09-17). "Amanat 5 September 1945". Special Province of Daerah Istimewa Yogyakarta Government. Retrieved 2023-06-22.

- ^ Adryamarthanino, Verelladevanka (2021-11-03). Nailufar, Nibras Nada (ed.). "Amanat 5 September 1945: Bergabungnya Yogyakarta dengan NKRI Halaman all". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ The position of special regions at the level of provinces or at the level of regencies, or at the level of villages only existed in 1948 through Law 22/1948 (UU 22/1948), even though DIS had been frozen/dissolved smoothly in 1946 two years before the law was passed.

- ^ Since 1957, it has been the territory of DIY

- ^ Samroni, Imam (2010). Daerah Istimewa Surakarta. Pura Pustaka Yogyakarta.

- ^ "Indonesian Traditional States part 1". www.worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^ Negoro, Suryo. "Sri Mangkoenagoro IX". Joglosemar Online. Retrieved 2010-04-28.

- ^ Evita, Andi Lili (2017). Gubernur Pertama Di Indonesia. Direktorat Sejarah, Direktorat Jenderal Kebudayaan, Kementerian Pendidikan dan Kebudayaan. ISBN 978-602-1289-72-3.

- ^ Kartodirdjo, Sartono (1993). Pengantar sejarah Indonesia baru : sejarah pergerakan nasional dari kolonialisme sampai nasionalisme (in Indonesian) (3rd ed.). Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. pp. 108–109. ISBN 979-403-767-2.

- ^ Daerah Istimewa Surakarta - Tuduhan Pro Belanda dan Kesetiaannya kepada Republik Indonesia, retrieved 2023-06-28

- ^ a b Joko Darmawan (2017). Mengenal Budaya Nasional "Trah Raja-raja Mataram di Tanah Jawa". Yogyakarta: Deepublish. ISBN 9786024532413.

- ^ a b Johari, Hendi (2019-05-17). "Di Bawah Simbol Banteng". Historia - Majalah Sejarah Populer Pertama di Indonesia (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-06-28.

- ^

a

b

tirto

.id /penculikan-pakubuwono-xii-dan-dihapusnya-daerah-istimewa-surakarta-f8aC - ^

a

b

c Sutiyah, Sutiyah (2017-09-19).

"KEHIDUPAN POLITIK DI KOTA SURAKARTA DAN YOGYAKARTA MENJELANG PEMILIHAN UMUM 1955". Paramita: Historical Studies Journal (in Indonesian). 27 (2). Universitas Negeri Semarang: 198.

doi:

10.15294/paramita.v27i2.11164 (inactive 31 January 2024).

ISSN

2407-5825.

{{ cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of January 2024 ( link) - ^ "Sejarah Peristiwa 3 Juli 1946, Kudeta Pertama di Indonesia". tirto.id (in Indonesian). 3 July 2019. Retrieved 2019-08-17.

- ^ Matanasi, Petrik (29 December 2020). "Penculikan Pakubuwono XII dan Dihapusnya Daerah Istimewa Surakarta". tirto.id (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-01-29.

- ^ a b "Kisah Penculikan Sjahrir". Historia - Majalah Sejarah Populer Pertama di Indonesia (in Indonesian). 2019-11-04. Retrieved 2023-06-23.

- ^ a b Soeharto; Dwipayana, G.; Hadimadja, Ramadhan Karta (1991). Soeharto, My Thoughts, Words, and Deeds: An Autobiography. Citra Lamtoro Gung Persada. ISBN 978-979-8085-01-7.

- ^ Prasadana, Muhammad Anggie Farizqi; Gunawan, Hendri (2019-06-17). "Keruntuhan Birokrasi Tradisional di Kasunanan Surakarta". Handep: Jurnal Sejarah Dan Budaya (in Indonesian). 2 (2). Balai Pelestarian Budaya Kalimantan Barat: 196. doi: 10.33652/handep.v2i2.36. ISSN 2684-7256. S2CID 198039293.

- ^ "Gedung Lawas Bank Indonesia Solo, Pernah Dipakai PM Sutan Sjahrir di Era Kemerdekaan Indonesia". Dinas Komunikasi, Informatika, Statistik dan Persandian Kota Surakarta. 18 February 2023.

- ^ "Keraton Surakarta Tuntut Status Istimewa". Constitutional Court of Indonesia. Archived from the original on 2020-06-19. Retrieved 2019-10-30.

- ^ "Selayang Pandang Kota Surakarta". DPRD Kota Surakarta.

- ^ "UU No. 16 Tahun 1947 tentang Pembentukan Haminte-Kota Surakarta [JDIH BPK RI]". peraturan.bpk.go.id. Retrieved 2023-06-27.

- ^ "Profil Jawa Tengah". jawatengah.go.id. Archived from the original on 29 June 2006. Retrieved 20 June 2023 – via Archive.org.

- ^ a b Putri Musaparsih, Cahya (2005). "Strategi Komite Nasional Indonesia Daerah Surakarta (KNIDS) dalam mengambil alih Swapraja, 1945-1946" (PDF). Skripsi. Jurusan Ilmu Sejarah, Fakultas Sastra dan Seni Rupa, Universitas Sebelas Maret Surakarta.

- ^ Setiadi, Bram; Trihandayani, D.S.; Hadi, Qomarul (2001). Raja di Alam Republik: Keraton Kesunanan Surakarta dan Paku Buwono XII. Jakarta: Bina Rena Pariwara.

- ^ a b Yosodipura, K. R. M. H. (1994). Karaton Surakarta Hadiningrat Bangunan Budaya Jawa sebagai Tuntunan Hidup. Pembangunan Budi Pakarti Kejawen.

- ^ Media, Kompas Cyber (2023-02-05). "Sri Susuhunan Pakubuwono XII, Pernah Diculik Barisan Banteng Halaman all". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-07-10.

-

^ Yuniyati, Winahyu Adha (2014).

"Kedudukan Selir Pakubuwana XII Di Keraton Surakarta (1944 – 2004)" (in Indonesian).

{{ cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=( help) - ^ "Masyarakat Surakarta Tuntut Dikembalikannya Daerah Istimewa Surakarta". detiknews (in Indonesian). 14 December 2010. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ Pradana, Rifky (2010-12-15). "Daerah Istimewa Surakarta, Cemburu Jogja?". KOMPASIANA (in Indonesian). Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ "Tuntut Daerah Istimewa, Trah Keraton Surakarta Ingin Lepas dari Jateng". detiknews (in Indonesian). 26 June 2013. Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ a b Adhi Nugroho, Wisnu (7 July 2013). "Ganjar Tunggu Putuskan MK Terkait Pembentukan Provinsi Daerah Istimewa Surakarta". Antara News (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ Parwito (8 July 2013). "Ganjar nilai wacana pemekaran Surakarta berasal dari keraton". merdeka.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 11 July 2023.

- ^ Susilo, Joko (2014-03-27). "MK tolak gugatan ahli waris Keraton Surakarta". Antara News. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ Fadjri, Raihul (2014-03-31). "Menteri Roy: Status Istimewa Surakarta Ditolak karena Sejarah". Tempo. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

- ^ Sunaryo, Arie (2014-03-30). "Roy Suryo dukung MK tolak Daerah Istimewa Surakarta". merdeka.com. Retrieved 2023-07-10.

See also

- Provinces of Indonesia

- Central Java

- History of Surakarta

- Surakarta Sunanate

- Special Region of Yogyakarta