Mfinda is a spiritual concept of the forest in Kongo religion.

Belief

Nature is essential to Kongo spirituality. While simbi (pl. bisimbi) nature spirits later became more associated with water, or kalûnga, they were also known to dwell in the forest, or mfinda (finda in Hoodoo). The Kingdom of Kongo used the term chibila, which referred to sacred groves, where they would venerate these forest spirits. The Kingdom of Loango called them bakisi banthandu, or spirits of the wilderness. [1] The Kingdom of Ndongo preferred the name xibila (pl. bibila). [2]

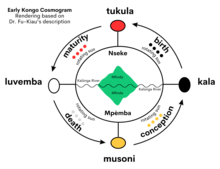

The Kongo people also believed that some ancestors inhabited the forest after death and maintained their spiritual presence in their descendants' lives. These particular ancestors were believed to have died, traveled to Mpémba, and then were reborn as bisimbi. Thus, The Great Mfinda existed as a meeting point between the physical world and the spiritual world. The living saw it as a source of physical nourishment through hunting and spiritual nourishment through contact with the ancestors. One expert on Kongo religion, Dr. Fu-Kiau, even described some precolonial Kongo cosmograms with mfinda as a bridge between the two worlds. [1]

Nganga

Mfinda is also where Kongo secret societies, such as Kinkimba and Lemba, initiated new healers. Expert healers, known as banganga (sing. nganga) underwent extensive training to commune with the ancestors in the spiritual realm and seek guidance from them. These new initiates learned how to locate nature spirits and build a connection. Once they became official banganga, it became their duty to seek them out in the forest and venerated them with shrines, sacred trees, and minkisi (sing. nkisi). In return, the ancestor or nature spirit would pass on untold history, advise the nganga, or allow them to harness their powers for healing or protection. [1]

American diaspora

The concept of mfinda as a spiritual space also emerged in the colonial United States through trans-Atlantic slavery and became known locally as finda. Bakongo descendants saw the wilderness as a symbol of freedom but also sorrow. Because early enslaved Bakongo had no ancestors on this side of kalûnga (which became synonymous with the Atlantic Ocean), it meant they had no blood tie to the new lands in which they were transported. [1] Thus, banganga had no way to connect to the spiritual world. To remedy this, some Bakongo and Mbundu willingly committed acts of sacrificial suicide so that they could become ancestors or simbi and connect the living to Mpémba, the spiritual world. The finda then became a sacred space, where sightings of "cymbee" spirits were often recorded by Black Americans. Today, the finda is still a significant element in Hoodoo. [1]

References

- ^ a b c d e Brown, Ras Michael (2012). African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry (1st ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26, 27, 90–102, 106–110, 119–121, 123. ISBN 978-1-107-66882-9.

- ^ Dennett, Richard Edward (1906). At the Back of the Black Man's Mind; Or Notes on the Kingly Office in West Africa. Forgotten Books. pp. 114–118. ISBN 9781605060118.

Mfinda is a spiritual concept of the forest in Kongo religion.

Belief

Nature is essential to Kongo spirituality. While simbi (pl. bisimbi) nature spirits later became more associated with water, or kalûnga, they were also known to dwell in the forest, or mfinda (finda in Hoodoo). The Kingdom of Kongo used the term chibila, which referred to sacred groves, where they would venerate these forest spirits. The Kingdom of Loango called them bakisi banthandu, or spirits of the wilderness. [1] The Kingdom of Ndongo preferred the name xibila (pl. bibila). [2]

The Kongo people also believed that some ancestors inhabited the forest after death and maintained their spiritual presence in their descendants' lives. These particular ancestors were believed to have died, traveled to Mpémba, and then were reborn as bisimbi. Thus, The Great Mfinda existed as a meeting point between the physical world and the spiritual world. The living saw it as a source of physical nourishment through hunting and spiritual nourishment through contact with the ancestors. One expert on Kongo religion, Dr. Fu-Kiau, even described some precolonial Kongo cosmograms with mfinda as a bridge between the two worlds. [1]

Nganga

Mfinda is also where Kongo secret societies, such as Kinkimba and Lemba, initiated new healers. Expert healers, known as banganga (sing. nganga) underwent extensive training to commune with the ancestors in the spiritual realm and seek guidance from them. These new initiates learned how to locate nature spirits and build a connection. Once they became official banganga, it became their duty to seek them out in the forest and venerated them with shrines, sacred trees, and minkisi (sing. nkisi). In return, the ancestor or nature spirit would pass on untold history, advise the nganga, or allow them to harness their powers for healing or protection. [1]

American diaspora

The concept of mfinda as a spiritual space also emerged in the colonial United States through trans-Atlantic slavery and became known locally as finda. Bakongo descendants saw the wilderness as a symbol of freedom but also sorrow. Because early enslaved Bakongo had no ancestors on this side of kalûnga (which became synonymous with the Atlantic Ocean), it meant they had no blood tie to the new lands in which they were transported. [1] Thus, banganga had no way to connect to the spiritual world. To remedy this, some Bakongo and Mbundu willingly committed acts of sacrificial suicide so that they could become ancestors or simbi and connect the living to Mpémba, the spiritual world. The finda then became a sacred space, where sightings of "cymbee" spirits were often recorded by Black Americans. Today, the finda is still a significant element in Hoodoo. [1]

References

- ^ a b c d e Brown, Ras Michael (2012). African-Atlantic Cultures and the South Carolina Lowcountry (1st ed.). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press. pp. 26, 27, 90–102, 106–110, 119–121, 123. ISBN 978-1-107-66882-9.

- ^ Dennett, Richard Edward (1906). At the Back of the Black Man's Mind; Or Notes on the Kingly Office in West Africa. Forgotten Books. pp. 114–118. ISBN 9781605060118.