The topic of this article may not meet Wikipedia's

notability guideline for biographies. (April 2024) |

Mabel Tolkien (née Suffield, 1870 – 1904) was the mother of J.R.R. Tolkien. She acted as Tolkien's tutor both in early life and in preparation for grammar school, and was an influence on his life, faith, and writing. Tolkien traced his interest in philology and romance to her, and his awareness of her hard work and suffering for the sake of her sons, especially when she was rejected by her family because of her conversion to Catholicism, left a lasting impact on him, as did her early death.

Life

Family

She was born in 1870 in Birmingham, the second daughter of John Suffield and his wife Emily, née Sparrow. The family was prosperous until Suffield’s drapery business went bankrupt and he became a travelling salesman. [1]

Marriage

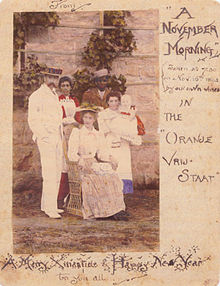

When Mabel was eighteen, she received a proposal of marriage from Arthur Tolkien, a bank clerk, who was thirteen years her senior. Her father did not allow a formal betrothal on the grounds that Mabel was too young and Arthur was unable to support her. [2] Arthur moved to Bloemfontein, South Africa, to become the manager of the Bloemfontein branch of the Bank of Africa, and Mabel joined him in March 1891. They married in Cape Town the following month. They had two sons, John Ronald Reuel (b. January 1892) and Hilary Arthur (b. February 1894); J.R.R.’s health struggled in the South African climate. [3]

In April 1895, Mabel brought her sons to England for a visit. Arthur, who had remained in Bloemfontein to work, contracted rheumatic fever and died in February 1896.

After staying with her parents, Mabel moved with her sons a cottage near Sarehole Mill, Birmingham, which she rented using the proceeds from Arthur’s share in a gold mine and support from her family. [4]

Catholicism

In 1900, Mabel and her sister May Incledon converted to Catholicism. [5] Her family, who were Methodist, disapproved: her father disowned her, [6] and her brother-in-law Walter Incledon, who had been assisting her financially, withdrew his support. May was forbidden by her husband to attend Catholic services, but Mabel persevered in her faith, taking her sons to Mass and arranging for them to attend a school conducted by the Birmingham Oratory, where she rented a house next door. [7]

Educating her sons

Mabel taught her sons to read and write, and then taught them Latin, French, botany, and drawing, and instructed them in the Catholic faith. She is credited with a talent and enthusiasm for languages, nature, calligraphy and etymology, which she passed on to Tolkien; [8] he cites her as the origin of his interest in 'philology' and 'romance,' [9] although she was unable to interest him in her other strength, the piano.

She moved the family several times to facilitate Tolkien’s education, withdrawing him from St Philip’s School to tutor him herself when she realised that he was outpacing his classmates. She 'set up a rigorous programme' in which she taught 'all the subjects herself,' except geometry, which was taught by one of her sisters. [10] This led to his winning a Foundation Scholarship to King Edward’s School in 1903. [11]

Death

In 1904, Mabel was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. Her friend Father Francis Xavier Morgan, who lived nearby in the Oratory which conducted St Philip’s School, arranged for the family to rent rooms in the Oratory’s lodge cottage, where Mabel died in November 1904. Father Francis became the guardian of her sons. [12]

Influence on Tolkien

The Suffields and the Tooks

Tolkien wrote that, 'Though a Tolkien by name, I am a Suffield by tastes, talents and upbringing.' [13] His connection with the West Midlands and his artistic and calligraphic talents (the Suffields were platemakers, engravers, and booksellers, and Mabel taught Tolkien calligraphy) comes from his mother’s side of the family. [14] His sense of the split between both sides of his heritage is thought to have contributed to the 'double-sided' nature of his character Bilbo Baggins, who traces some of his attributes to his maternal 'Tookish' side. [15] 'The Old Took and his three remarkable daughters' is thought to be an allusion to Mabel and her family. [16] Mabel’s sister Jane Neave also owned a farm called Bag End, where Tolkien was sent to stay during Mabel's illness, which became the name of Bilbo’s home. [17]

Catholicism

Mabel’s Catholic convictions had a lasting impact on Tolkien; she lived to see him take his first communion. He said of her, 'My own dear mother was a martyr indeed, and it is not to everybody that God grants to easy a way to His great gifts as He did to Hilary and myself, giving us a mother who killed herself with labour and trouble to ensure us keeping the faith.' [18]

In popular culture

Mabel Tolkien was portrayed by Laura Donelly in the 2019 film Tolkien.

References

- ^ Heims, Neil (2013). J.R.R. Tolkien. Infobase Learning. ISBN 978-1-4381-4838-0.

- ^ Xander, Jesse (2021-05-12). The Real JRR Tolkien: The Man Who Created Middle-Earth. White Owl. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-5267-6516-1.

- ^ Duriez, Colin (2012). J R R Tolkien: The Making of a Legend. Lion Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7459-5514-8.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey (2011-04-28). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. HarperCollins UK. pp. 17–24. ISBN 978-0-00-738125-8.

- ^ Pearce, Joseph (2019-07-02). Tolkien: Man and Myth. Ignatius Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-64229-091-2.

- ^ Tubbs, Patricia, 'Suffield Family' in J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, ed. M. Drout, p. 628.

- ^ Carpenter (2011) pp. 31–2.

- ^ Lee, Stuart D. (2022-08-01). A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien. John Wiley & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-119-69140-2.

- ^ Letter 165, June 1955.

- ^ Amelia Harper, 'Education,' in J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, ed. M. Drout, p. 142.

- ^ Carpenter (2011) pp. 25–30.

- ^ Carpenter (2011) pp. 36–9.

- ^ Letter 44, 18 March 1941.

- ^ Garth, John (2013-06-11). Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth. HMH. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-544-26372-7.

- ^ Moseley, Charles (1995). J. R. R. Tolkien. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-7463-0763-2.

- ^ Carpenter (2011), p. 196.

- ^ Carpenter (2011), p. 197.

- ^ Carpenter (2011), p. 39.

The topic of this article may not meet Wikipedia's

notability guideline for biographies. (April 2024) |

Mabel Tolkien (née Suffield, 1870 – 1904) was the mother of J.R.R. Tolkien. She acted as Tolkien's tutor both in early life and in preparation for grammar school, and was an influence on his life, faith, and writing. Tolkien traced his interest in philology and romance to her, and his awareness of her hard work and suffering for the sake of her sons, especially when she was rejected by her family because of her conversion to Catholicism, left a lasting impact on him, as did her early death.

Life

Family

She was born in 1870 in Birmingham, the second daughter of John Suffield and his wife Emily, née Sparrow. The family was prosperous until Suffield’s drapery business went bankrupt and he became a travelling salesman. [1]

Marriage

When Mabel was eighteen, she received a proposal of marriage from Arthur Tolkien, a bank clerk, who was thirteen years her senior. Her father did not allow a formal betrothal on the grounds that Mabel was too young and Arthur was unable to support her. [2] Arthur moved to Bloemfontein, South Africa, to become the manager of the Bloemfontein branch of the Bank of Africa, and Mabel joined him in March 1891. They married in Cape Town the following month. They had two sons, John Ronald Reuel (b. January 1892) and Hilary Arthur (b. February 1894); J.R.R.’s health struggled in the South African climate. [3]

In April 1895, Mabel brought her sons to England for a visit. Arthur, who had remained in Bloemfontein to work, contracted rheumatic fever and died in February 1896.

After staying with her parents, Mabel moved with her sons a cottage near Sarehole Mill, Birmingham, which she rented using the proceeds from Arthur’s share in a gold mine and support from her family. [4]

Catholicism

In 1900, Mabel and her sister May Incledon converted to Catholicism. [5] Her family, who were Methodist, disapproved: her father disowned her, [6] and her brother-in-law Walter Incledon, who had been assisting her financially, withdrew his support. May was forbidden by her husband to attend Catholic services, but Mabel persevered in her faith, taking her sons to Mass and arranging for them to attend a school conducted by the Birmingham Oratory, where she rented a house next door. [7]

Educating her sons

Mabel taught her sons to read and write, and then taught them Latin, French, botany, and drawing, and instructed them in the Catholic faith. She is credited with a talent and enthusiasm for languages, nature, calligraphy and etymology, which she passed on to Tolkien; [8] he cites her as the origin of his interest in 'philology' and 'romance,' [9] although she was unable to interest him in her other strength, the piano.

She moved the family several times to facilitate Tolkien’s education, withdrawing him from St Philip’s School to tutor him herself when she realised that he was outpacing his classmates. She 'set up a rigorous programme' in which she taught 'all the subjects herself,' except geometry, which was taught by one of her sisters. [10] This led to his winning a Foundation Scholarship to King Edward’s School in 1903. [11]

Death

In 1904, Mabel was diagnosed with Type 1 diabetes. Her friend Father Francis Xavier Morgan, who lived nearby in the Oratory which conducted St Philip’s School, arranged for the family to rent rooms in the Oratory’s lodge cottage, where Mabel died in November 1904. Father Francis became the guardian of her sons. [12]

Influence on Tolkien

The Suffields and the Tooks

Tolkien wrote that, 'Though a Tolkien by name, I am a Suffield by tastes, talents and upbringing.' [13] His connection with the West Midlands and his artistic and calligraphic talents (the Suffields were platemakers, engravers, and booksellers, and Mabel taught Tolkien calligraphy) comes from his mother’s side of the family. [14] His sense of the split between both sides of his heritage is thought to have contributed to the 'double-sided' nature of his character Bilbo Baggins, who traces some of his attributes to his maternal 'Tookish' side. [15] 'The Old Took and his three remarkable daughters' is thought to be an allusion to Mabel and her family. [16] Mabel’s sister Jane Neave also owned a farm called Bag End, where Tolkien was sent to stay during Mabel's illness, which became the name of Bilbo’s home. [17]

Catholicism

Mabel’s Catholic convictions had a lasting impact on Tolkien; she lived to see him take his first communion. He said of her, 'My own dear mother was a martyr indeed, and it is not to everybody that God grants to easy a way to His great gifts as He did to Hilary and myself, giving us a mother who killed herself with labour and trouble to ensure us keeping the faith.' [18]

In popular culture

Mabel Tolkien was portrayed by Laura Donelly in the 2019 film Tolkien.

References

- ^ Heims, Neil (2013). J.R.R. Tolkien. Infobase Learning. ISBN 978-1-4381-4838-0.

- ^ Xander, Jesse (2021-05-12). The Real JRR Tolkien: The Man Who Created Middle-Earth. White Owl. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-5267-6516-1.

- ^ Duriez, Colin (2012). J R R Tolkien: The Making of a Legend. Lion Books. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-7459-5514-8.

- ^ Carpenter, Humphrey (2011-04-28). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. HarperCollins UK. pp. 17–24. ISBN 978-0-00-738125-8.

- ^ Pearce, Joseph (2019-07-02). Tolkien: Man and Myth. Ignatius Press. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-64229-091-2.

- ^ Tubbs, Patricia, 'Suffield Family' in J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, ed. M. Drout, p. 628.

- ^ Carpenter (2011) pp. 31–2.

- ^ Lee, Stuart D. (2022-08-01). A Companion to J. R. R. Tolkien. John Wiley & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-119-69140-2.

- ^ Letter 165, June 1955.

- ^ Amelia Harper, 'Education,' in J.R.R. Tolkien Encyclopedia, ed. M. Drout, p. 142.

- ^ Carpenter (2011) pp. 25–30.

- ^ Carpenter (2011) pp. 36–9.

- ^ Letter 44, 18 March 1941.

- ^ Garth, John (2013-06-11). Tolkien and the Great War: The Threshold of Middle-earth. HMH. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-544-26372-7.

- ^ Moseley, Charles (1995). J. R. R. Tolkien. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-7463-0763-2.

- ^ Carpenter (2011), p. 196.

- ^ Carpenter (2011), p. 197.

- ^ Carpenter (2011), p. 39.