This article has multiple issues. Please help

improve it or discuss these issues on the

talk page. (

Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

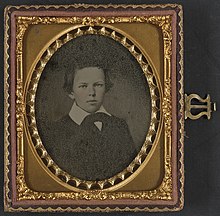

Leroy Wiley Gresham (November 11, 1847 – June 18, 1865) was born in Macon, Georgia, and left behind one of the most remarkable and important diaries ever published. [1] The seven journals, edited and annotated by Janet E. Croon, were published June 1, 2018 by Savas Beatie under the title The War Outside My Window: The Civil War Journals of LeRoy Wiley Gresham, 1860-1865. The book includes the tagline: A remarkable account of the collapse of the Old South, and the final years of a privileged but afflicted life. The book won two major awards and was a finalist for a third.

Selections from his diary appeared in a Library of Congress exhibit, "The Civil War in America", from 2012-2013, and were reprinted in Harper's Magazine. [2] and featured in a major article in The Washington Post. This is the only teenage male diary of a civilian spanning this time-period in existence, which makes them truly unique. [3]

LeRoy was severely injured when a chimney collapsed on him and crushed his left leg in 1856. [2] He was semi-mobile thereafter, but developed other more serious medical issues related to a slow and agonizing disease that would eventually kill him. LeRoy spent almost all of his time sitting, reclining, or confined to a special wagon pulled about town by family members or slaves. In 1860, LeRoy's mother, Mary Gresham, gave him a journal to write in when he was about to leave with his father, John Gresham, for Philadelphia to see a specialist about "his condition." LeRoy (or "Loy" as he was known to his family) began writing in June of that year and only stopped five years later just before his death a handful of weeks after the war ended. [4]

A companion book dedicated solely to his medical condition was concurrently published as I Am Perhaps Dying: The Medical Backstory of Spinal Tuberculosis Hidden in the Civil War Diary of LeRoy Wiley Gresham, by Dr. Dennis Rasbach (Savas Beatie, 2018).

The equivalent of an intelligent and informed mid-19th century blogger, LeRoy's diaries offer deep insight into the life of a prominent slave-holding Southern family, the secession crisis, the four-year American Civil War, slavery (his family owned 100 slaves on two plantations in Houston County, GA) and the rapidly changing world as seen and understood through the eyes of an exceptionally bright and well-educated teenager. LeRoy played chess, loved Shakespeare, was a voracious reader, and dealt with his own situation and deteriorating health with amazing strength and fortitude, even while plied with every remedy possible and dosed with morphine and opium.

The Gresham journal is also unique because it is the only known 19th Century account that meticulously details, on a daily basis for five years, the course of a fatal disease (which is carefully identified in both books by a medical expert). The entries offer details on the treatments given to LeRoy by his doctors and family, his physical ailments (fever, abscesses, coughing, chronic pain, etc.), how the drugs affected him, and his steady decline until death.

The son of John J. and Mary Gresham, [1] [5] LeRoy is interred in Macon, Georgia in the Rose Hill Cemetery, Magnolia Section. [1] His father was "twice mayor," a prominent businessman, judge, and attorney. [2]

His mother, (née Mary Baxter 1822), is the sister of Sallie Bird; [5] thus he is briefly mentioned in correspondence kept in the Baxter-Bird-Smith Family Papers of the University of Georgia Libraries. [6]

Further reading

References

- ^ a b c USGenWeb Archives USGenWeb Archives, Rose Hill Cemetery Magnolia Section

- ^ a b c Southern Discomfort by LeRoy Wiley Gresham, April 2013, Harper's Magazine

- ^ Finding Aid, Lewis H. Machen Family, A Register of Its Papers in the Library of Congress. Prepared by John McDonough and David Mathisen & Revised by Patrick Kerwin. Latest revision: 2004-10-21. Catalog record permalink: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm77086777. Michael Ruane, Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/invalid-boys-diary-focus-of-library-of-congress-civil-war-exhibit/2012/11/08/c55c7758-21db-11e2-8448-81b1ce7d6978_story.html

- ^ Invalid boy’s diary focus of Library of Congress Civil War exhibit. The Washington Post. By Michael E. Ruane, November 08, 2012

- ^ a b page (xxxvi), John Rozier, ed., The Granite Farm Letters: The Civil War Correspondence of Edgeworth and Sallie Bird (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988).

- ^ (e.g. "Bud is writing to Cousin Leroy" page 10; see footnote page 28, John Rozier, ed., The Granite Farm Letters: The Civil War Correspondence of Edgeworth and Sallie Bird (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988).

Primary sources

- Selections of his diary from the online version of the Library of Congress exhibit

Additional sources

- Clarke County, Georgia Census 1860.

- Macon teen’s diary provides perspective on Civil War, The Telegraph, December 15, 2012 Liz Fabian

- Short biography from "Voices of the Civil War" at Library of Congress online

- Invalid Teenager's Diary Published

This article has multiple issues. Please help

improve it or discuss these issues on the

talk page. (

Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Leroy Wiley Gresham (November 11, 1847 – June 18, 1865) was born in Macon, Georgia, and left behind one of the most remarkable and important diaries ever published. [1] The seven journals, edited and annotated by Janet E. Croon, were published June 1, 2018 by Savas Beatie under the title The War Outside My Window: The Civil War Journals of LeRoy Wiley Gresham, 1860-1865. The book includes the tagline: A remarkable account of the collapse of the Old South, and the final years of a privileged but afflicted life. The book won two major awards and was a finalist for a third.

Selections from his diary appeared in a Library of Congress exhibit, "The Civil War in America", from 2012-2013, and were reprinted in Harper's Magazine. [2] and featured in a major article in The Washington Post. This is the only teenage male diary of a civilian spanning this time-period in existence, which makes them truly unique. [3]

LeRoy was severely injured when a chimney collapsed on him and crushed his left leg in 1856. [2] He was semi-mobile thereafter, but developed other more serious medical issues related to a slow and agonizing disease that would eventually kill him. LeRoy spent almost all of his time sitting, reclining, or confined to a special wagon pulled about town by family members or slaves. In 1860, LeRoy's mother, Mary Gresham, gave him a journal to write in when he was about to leave with his father, John Gresham, for Philadelphia to see a specialist about "his condition." LeRoy (or "Loy" as he was known to his family) began writing in June of that year and only stopped five years later just before his death a handful of weeks after the war ended. [4]

A companion book dedicated solely to his medical condition was concurrently published as I Am Perhaps Dying: The Medical Backstory of Spinal Tuberculosis Hidden in the Civil War Diary of LeRoy Wiley Gresham, by Dr. Dennis Rasbach (Savas Beatie, 2018).

The equivalent of an intelligent and informed mid-19th century blogger, LeRoy's diaries offer deep insight into the life of a prominent slave-holding Southern family, the secession crisis, the four-year American Civil War, slavery (his family owned 100 slaves on two plantations in Houston County, GA) and the rapidly changing world as seen and understood through the eyes of an exceptionally bright and well-educated teenager. LeRoy played chess, loved Shakespeare, was a voracious reader, and dealt with his own situation and deteriorating health with amazing strength and fortitude, even while plied with every remedy possible and dosed with morphine and opium.

The Gresham journal is also unique because it is the only known 19th Century account that meticulously details, on a daily basis for five years, the course of a fatal disease (which is carefully identified in both books by a medical expert). The entries offer details on the treatments given to LeRoy by his doctors and family, his physical ailments (fever, abscesses, coughing, chronic pain, etc.), how the drugs affected him, and his steady decline until death.

The son of John J. and Mary Gresham, [1] [5] LeRoy is interred in Macon, Georgia in the Rose Hill Cemetery, Magnolia Section. [1] His father was "twice mayor," a prominent businessman, judge, and attorney. [2]

His mother, (née Mary Baxter 1822), is the sister of Sallie Bird; [5] thus he is briefly mentioned in correspondence kept in the Baxter-Bird-Smith Family Papers of the University of Georgia Libraries. [6]

Further reading

References

- ^ a b c USGenWeb Archives USGenWeb Archives, Rose Hill Cemetery Magnolia Section

- ^ a b c Southern Discomfort by LeRoy Wiley Gresham, April 2013, Harper's Magazine

- ^ Finding Aid, Lewis H. Machen Family, A Register of Its Papers in the Library of Congress. Prepared by John McDonough and David Mathisen & Revised by Patrick Kerwin. Latest revision: 2004-10-21. Catalog record permalink: http://lccn.loc.gov/mm77086777. Michael Ruane, Washington Post, https://www.washingtonpost.com/entertainment/museums/invalid-boys-diary-focus-of-library-of-congress-civil-war-exhibit/2012/11/08/c55c7758-21db-11e2-8448-81b1ce7d6978_story.html

- ^ Invalid boy’s diary focus of Library of Congress Civil War exhibit. The Washington Post. By Michael E. Ruane, November 08, 2012

- ^ a b page (xxxvi), John Rozier, ed., The Granite Farm Letters: The Civil War Correspondence of Edgeworth and Sallie Bird (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988).

- ^ (e.g. "Bud is writing to Cousin Leroy" page 10; see footnote page 28, John Rozier, ed., The Granite Farm Letters: The Civil War Correspondence of Edgeworth and Sallie Bird (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1988).

Primary sources

- Selections of his diary from the online version of the Library of Congress exhibit

Additional sources

- Clarke County, Georgia Census 1860.

- Macon teen’s diary provides perspective on Civil War, The Telegraph, December 15, 2012 Liz Fabian

- Short biography from "Voices of the Civil War" at Library of Congress online

- Invalid Teenager's Diary Published