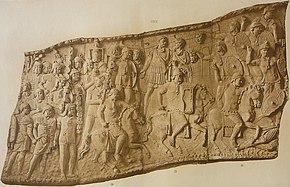

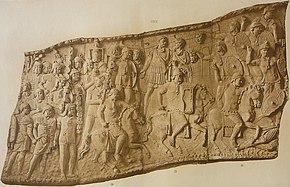

The focale (plural focalia), also known as a sudarium ("sweat cloth"), [1] was a woolen or linen scarf worn by ancient Roman military personnel. It protected the neck from chafing by the armor and was used for warmth. [2] [3] [4] The focale is depicted widely in military scenes from Roman art, such as the relief sculpture on the Arch of Septimius Severus in the Roman Forum [5] and Trajan's Column. [6] It is shown loosely knotted in the front, but is sometimes visible with the ends tucked inside the cuirass. [1]

In Latin literature, focale is a general word for a scarf or wrapping for the throat. [7] A focale was one of the gifts that might be given for the December festival of Saturnalia, according to Martial. [8] In one of his satires, Horace lists focalia among the "badges of illness" (insignia morbi). [9] In describing the correct attire for public speaking, Quintilian advises against wearing a focale, unless required by poor health. [10]

Although a sudarium often is used as a handkerchief, it can be worn like the focale as a neckerchief. [11] When Suetonius describes the overly casual attire of Nero, the emperor is barefoot, unbelted, and dressed in evening wear ( synthesis), with a sudarium around his neck. [12] The sudarium may be the precursor to the focale. [13] In late antiquity, orarium (Greek orarion) might be synonymous with focale, as in the description of military attire in the Vision of Dorotheus, and in a papyrus (dated 350–450 AD) listing military clothes. [14] From the sudarium derives the name of the Near Eastern sudra, a similar piece of cloth with various functions over time. [15]

The focale is sometimes seen as one of the precursors of the necktie. [16] Cesare Vecellio (1530–1606) mentions the focale, calling it a cravata ( cravat), as worn by Roman soldiers in his book on the history of fashion. [17] It has been compared to the amice (amictus) worn by Roman Catholic priests, which is depicted from the 6th century onward, as in the Ravenna mosaics. [18]

References

- ^ a b Jason R. Abdal, Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg (Trafford, 2013), pp. 166-167.

- ^ Nic Fields , The Roman Army of the Principate 27 BC-AD 117 (Osprey, 2009), p. 25.

- ^ Davies, Glenys; Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2007). Greek and Roman Dress from A to Z. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-134-58916-6.

- ^ Ermatinger, James W. (2015-08-11). The World of Ancient Rome: A Daily Life Encyclopedia: A Daily Life Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-4408-2908-6.

- ^ Richard Brilliant, " The Arch of Septimius Severus in the Roman Forum," Memoirs of the American Academy 29 (1967), pp. 139, 142, 155, 156, 158, 184, 186, 190, 197, 203, 210.

- ^ John Hungerford Pollen, A Description of the Trajan Column (London, 1874), p. 111.

- ^ Antoine Mongez, "Recherches sur les habillemens des anciens," Histoire et mémoires de l'Institute Royal de France 4 (1818), pp. 295–295.

- ^ Martial 14.137 (142).

- ^ Horace, Satires 2.8.255; article on "Dress," A Concise Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, edited by F. Warre Cornish (London, 1898), p. 259.

- ^ Quintilian 11.3.144. Legwarmers (fascias quibus crura vestiuntur) and earmuffs (aurium ligamenta) are likewise to be avoided.

- ^ Mongez, "Recherches sur les habillemens des anciens," p. 295.

- ^ Suetonius, Nero 51; Mongez, "Recherches sur les habillemens des anciens," p. 295.

- ^ D'Amato, Raffaele; Sumner, Graham (2009-09-17). Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier: From Marius to Commodus, 112 BC–AD 192. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-4738-1189-8.

- ^ SB VI.9570.5; Jan Bremmer, "An Imperial Palace Guard in Heaven: The Date of the Vision of Dorotheus," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 75 (1988), p. 86.

- ^ Aaron Michael, Butts (2018-12-06). Kiraz, George Anton (ed.). Latin Words in Classical Syriac. Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. Vol. 19. Gorgias Press. p. 134. doi: 10.31826/9781463240028. ISBN 978-1-4632-4002-8. S2CID 239370393.

- ^ Daniel K. Hall, How to Tie a Tie: Choosing, Coordinating, and Knotting Your Neckwear (Sterling, 2008), p. 8.

- ^ Oscar Lenius, The Well-Dressed Gentleman (LIT Verlag Münster, 2010), p. 93.

- ^ Charles Panati, Sacred Origins of Profound Things (Arkana, 1996), n.p.; Mongez, "Recherches sur les habillemens des anciens," p. 296.

The focale (plural focalia), also known as a sudarium ("sweat cloth"), [1] was a woolen or linen scarf worn by ancient Roman military personnel. It protected the neck from chafing by the armor and was used for warmth. [2] [3] [4] The focale is depicted widely in military scenes from Roman art, such as the relief sculpture on the Arch of Septimius Severus in the Roman Forum [5] and Trajan's Column. [6] It is shown loosely knotted in the front, but is sometimes visible with the ends tucked inside the cuirass. [1]

In Latin literature, focale is a general word for a scarf or wrapping for the throat. [7] A focale was one of the gifts that might be given for the December festival of Saturnalia, according to Martial. [8] In one of his satires, Horace lists focalia among the "badges of illness" (insignia morbi). [9] In describing the correct attire for public speaking, Quintilian advises against wearing a focale, unless required by poor health. [10]

Although a sudarium often is used as a handkerchief, it can be worn like the focale as a neckerchief. [11] When Suetonius describes the overly casual attire of Nero, the emperor is barefoot, unbelted, and dressed in evening wear ( synthesis), with a sudarium around his neck. [12] The sudarium may be the precursor to the focale. [13] In late antiquity, orarium (Greek orarion) might be synonymous with focale, as in the description of military attire in the Vision of Dorotheus, and in a papyrus (dated 350–450 AD) listing military clothes. [14] From the sudarium derives the name of the Near Eastern sudra, a similar piece of cloth with various functions over time. [15]

The focale is sometimes seen as one of the precursors of the necktie. [16] Cesare Vecellio (1530–1606) mentions the focale, calling it a cravata ( cravat), as worn by Roman soldiers in his book on the history of fashion. [17] It has been compared to the amice (amictus) worn by Roman Catholic priests, which is depicted from the 6th century onward, as in the Ravenna mosaics. [18]

References

- ^ a b Jason R. Abdal, Four Days in September: The Battle of Teutoburg (Trafford, 2013), pp. 166-167.

- ^ Nic Fields , The Roman Army of the Principate 27 BC-AD 117 (Osprey, 2009), p. 25.

- ^ Davies, Glenys; Llewellyn-Jones, Lloyd (2007). Greek and Roman Dress from A to Z. Routledge. p. 73. ISBN 978-1-134-58916-6.

- ^ Ermatinger, James W. (2015-08-11). The World of Ancient Rome: A Daily Life Encyclopedia: A Daily Life Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 289. ISBN 978-1-4408-2908-6.

- ^ Richard Brilliant, " The Arch of Septimius Severus in the Roman Forum," Memoirs of the American Academy 29 (1967), pp. 139, 142, 155, 156, 158, 184, 186, 190, 197, 203, 210.

- ^ John Hungerford Pollen, A Description of the Trajan Column (London, 1874), p. 111.

- ^ Antoine Mongez, "Recherches sur les habillemens des anciens," Histoire et mémoires de l'Institute Royal de France 4 (1818), pp. 295–295.

- ^ Martial 14.137 (142).

- ^ Horace, Satires 2.8.255; article on "Dress," A Concise Dictionary of Greek and Roman Antiquities, edited by F. Warre Cornish (London, 1898), p. 259.

- ^ Quintilian 11.3.144. Legwarmers (fascias quibus crura vestiuntur) and earmuffs (aurium ligamenta) are likewise to be avoided.

- ^ Mongez, "Recherches sur les habillemens des anciens," p. 295.

- ^ Suetonius, Nero 51; Mongez, "Recherches sur les habillemens des anciens," p. 295.

- ^ D'Amato, Raffaele; Sumner, Graham (2009-09-17). Arms and Armour of the Imperial Roman Soldier: From Marius to Commodus, 112 BC–AD 192. Frontline Books. ISBN 978-1-4738-1189-8.

- ^ SB VI.9570.5; Jan Bremmer, "An Imperial Palace Guard in Heaven: The Date of the Vision of Dorotheus," Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 75 (1988), p. 86.

- ^ Aaron Michael, Butts (2018-12-06). Kiraz, George Anton (ed.). Latin Words in Classical Syriac. Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. Vol. 19. Gorgias Press. p. 134. doi: 10.31826/9781463240028. ISBN 978-1-4632-4002-8. S2CID 239370393.

- ^ Daniel K. Hall, How to Tie a Tie: Choosing, Coordinating, and Knotting Your Neckwear (Sterling, 2008), p. 8.

- ^ Oscar Lenius, The Well-Dressed Gentleman (LIT Verlag Münster, 2010), p. 93.

- ^ Charles Panati, Sacred Origins of Profound Things (Arkana, 1996), n.p.; Mongez, "Recherches sur les habillemens des anciens," p. 296.