| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by

Citation bot (

talk |

contribs) 35 days ago. (

Update) |

Ta lista nietypowych śmierci zawiera niezwykłe lub niesamowicie rzadkie przypadki śmierci zapisane w historii i uznane jako niezwykłe poprzez kilka źródeł.

Antyk

| Imię osoby | Obraz | Data śmierci | Opis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menes | 3200 BC c. 3200 p.n.e | Egipski Faraon i jednoczyciel Górnego i Dolnego Egiptu został porwany a potem zabity przez hipopotama. [2] | |

| Drakon | 620 BC c. 620 p.n.e. | The Athenian lawmaker was reportedly smothered to death by gifts of cloaks and hats showered upon him by appreciative citizens at a theatre in Aegina, Greece. [3] | |

| Charondas |  |

700 BCc. 612 BC | According to Diodorus Siculus, the Greek lawgiver from Sicily issued a law that anyone who brought weapons into the Assembly must be put to death. One day, he arrived at the Assembly seeking help to defeat some brigands in the countryside, but with a knife still attached to his belt. In order to uphold his own law, he committed suicide. [4] [5] [6] |

| Arrhichion of Phigalia |  |

564 BC | The Greek pankratiast caused his own death during the Olympic finals. Held by his unidentified opponent in a stranglehold and unable to free himself, Arrhichion kicked his opponent, causing him so much pain from a foot/ankle injury that the opponent made the sign of defeat to the umpires, but at the same time broke Arrhichion's neck. Since the opponent had conceded defeat, Arrhichion was proclaimed the victor posthumously. [7] [8] |

| Milo of Croton |  |

600 BC 6th century BC | The Olympic champion wrestler's hands reportedly became trapped when he tried to split a tree apart; he was then devoured by wolves (or, in later versions, lions). [9] |

| Zeuxis |  |

500 BC 5th century BC | The Greek painter died of laughter while painting an elderly woman. [10] |

| Pythagoras of Samos |  |

495 BC c. 495 BC | Ancient sources disagree on how the Greek philosopher died, [11] [12] but one late and probably apocryphal legend reported by both Diogenes Laërtius, a third-century AD biographer of famous philosophers, and Iamblichus, a Neoplatonist philosopher, states that Pythagoras was murdered by his political enemies. Supposedly, he almost managed to outrun them, but he came to a bean field and refused to run through it, as he had prohibited beans as ritually unclean. [12] [13] Since cutting through the field would violate his own teachings, Pythagoras simply stopped running and was killed. This story may have been fabricated by Neanthes of Cyzicus, on whom both Diogenes and Iamblichus rely as a source. [12] |

| Anacreon |  |

485 BC c. 485 BC | The poet, known for works in celebration of wine, choked to death on a grape stone according to Pliny the Elder. The 1911 <i id="mwtQ">Encyclopædia Britannica</i> suggests that "the story has an air of mythical adaptation to the poet's habits". [10]: 104 |

| Heraclitus of Ephesus |  |

475 BC c. 475 BC | According to one account given by Diogenes Laërtius, the Greek philosopher was said to have been devoured by dogs after smearing himself with cow manure in an attempt to cure his dropsy. [14] [15] |

| Themistocles |  |

459 BC c. 459 BC | The Athenian general who won the Battle of Salamis actually died of natural causes in exile, [16] but was widely rumored to have committed suicide by drinking a solution of crushed minerals known as bull's blood. [17] [16] The legend is widely retold in classical sources. The early twentieth-century English classicist Percy Gardner proposed that the story about him drinking bull's blood may have been based on an ignorant misunderstanding of a statue showing Themistocles in a heroic pose, holding a cup as an offering to the gods. The comedic playwright Aristophanes references Themistocles drinking bull's blood in his comedy The Knights (performed in 424 BC) as the most heroic way for a man to die. [16] |

| Aeschylus |  |

455 BC c. 455 BC | According to Valerius Maximus, the eldest of the three great Athenian tragedians was killed by a tortoise dropped by an eagle that had mistaken his bald head for a rock suitable for shattering the shell of the reptile. Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, adds that Aeschylus had been staying outdoors to avert a prophecy that he would be killed that day "by the fall of a house". [10]: 104 [18] [19] [20] |

| Empedocles of Akragas |  |

430 BC c. 430 BC | According to Diogenes Laërtius, the Pre-Socratic philosopher from Sicily, who, in one of his surviving poems, declared himself to have become a "divine being... no longer mortal", [21] tried to prove he was an immortal god by leaping into Mount Etna, an active volcano. [22] This legend is also alluded to by the Roman poet Horace. |

| Sophocles |  |

406 BC c. 406 BC | A number of "remarkable" legends concerning the death of another of the three great Athenian tragedians are recorded in the late antique Life of Sophocles. According to one legend, he choked to death on an unripe grape. Another says that he died of joy after hearing that his last play had been successful. A third account reports that he died of suffocation, after reading aloud a lengthy monologue from the end of his play Antigone, without pausing to take a breath for punctuation. [20] |

| Mithridates | 401 BC | The Persian soldier who embarrassed his king, Artaxerxes II, by boasting of killing his rival, Cyrus the Younger (who was the brother of Artaxerxes II), was executed by scaphism. The king's physician, Ctesias, reported that Mithridates survived the insect torture for 17 days. [23] [24] | |

| Democritus of Abdera |  |

370 BC c. 370 BC | According to Diogenes Laërtius, the Greek Atomist philosopher died aged 109; as he was on his deathbed, his sister was greatly worried because she needed to fulfill her religious obligations to the goddess Artemis in the approaching three-day Thesmophoria festival. Democritus told her to place a loaf of warm bread under his nose, and was able to survive for the three days of the festival by sniffing it. He died immediately after the festival was over. [25] |

| Antiphanes | 310 BC c. 310 BC | According to the Suda, the renowned comic poet of the Middle Attic comedy died after being struck by a pear. [26] [27] | |

| Agathocles of Syracuse |  |

289 BC | The Greek tyrant of Syracuse was murdered with a poisoned toothpick. [10]: 104 |

| Philitas of Cos |  |

270 BC c. 270 BC | The Greek intellectual is said by Athenaeus to have studied arguments and erroneous word usage so intensely that he wasted away and starved to death. British classicist Alan Cameron speculates that Philitas died from a wasting disease which his contemporaries joked was caused by his pedantry. [28] |

| Zeno of Citium |  |

270 BC c. 262 BC | The Greek philosopher from Citium (Kition), Cyprus, tripped and fell as he was leaving the school, breaking his toe. Striking the ground with his fist, he quoted the line from the Niobe, "I come, I come, why dost thou call for me?" He died on the spot through holding his breath. [29] |

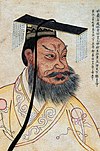

| Qin Shi Huang |  |

August 210 BC | The first emperor of China, whose artifacts and treasures include the Terracotta Army, died after ingesting several pills of mercury, in the belief that it would grant him eternal life. [30] [31] [32] |

| Chrysippus of Soli |  |

206 BC c. 206 BC | One ancient account of the death of the third-century BC Greek Stoic philosopher tells that he died of laughter after he saw a donkey eating his figs; he told a slave to give the donkey neat wine to drink with which to wash them down, and then, "...having laughed too much, he died" (Diogenes Laërtius 7.185). [33] |

| Eleazar Avaran |  |

163 BC c. 163 BC | According to 1 Maccabees 6:46, the brother of Judas Maccabeus thrust his spear in battle into the belly of a king's war elephant, which collapsed and fell on top of Eleazar, killing him instantly. [34] |

| Manius Aquillius and Marcus Licinius Crassus |   |

1 BC 1st Century BC | The late Roman Republic-era consul was sent as ambassador to Asia Minor in 90 BC to restore Nicomedes IV of Bithynia to his kingdom after the latter was expelled by Mithridates VI of Pontus. But Aquillius encouraged Nicomedes to raid part of Mithridates' territory, which started the First Mithridatic War. Aquillius was captured and brought to Mithridates, who in 88 BC had him executed by pouring molten gold down his throat. According to one story, Marcus Licinius Crassus, a Roman general and statesman, who was very greedy despite being called "the richest man in Rome," was executed in the same manner by the Parthians after they defeated him in the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, in symbolic mockery of his thirst for wealth. However, it has been disputed as to whether this is how Crassus met his end. |

| Porcia Catonis |  |

June 43 BC June 43 BC to October 42 BC | The daughter of Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis and second wife of Marcus Junius Brutus, according to ancient historians such as Cassius Dio and Appian, killed herself by swallowing hot coals. Modern historians find this tale implausible. [35] |

| Claudius Drusus |  |

20 c. 20 AD | According to Suetonius, the eldest son of the future Roman emperor Claudius died while playing with a pear. Having tossed the pear high in the air, he caught it in his mouth when it came back, but he choked on it, dying of asphyxia. [36] |

| Tiberius |  |

March 16, 37 | The Roman emperor died in Misenum aged 78. According to Tacitus, the emperor appeared to have died and Caligula, who was at Tiberius' villa, was being congratulated on his succession to the empire, when news arrived that the emperor had revived and was recovering his faculties. Those who had moments before recognized Caligula as Augustus fled in fear of the emperor's wrath, while Macro, a prefect of the Praetorian Guard, took advantage of the chaos to have Tiberius smothered with his own bedclothes, definitively killing him. [37] |

| Simon Peter |  |

1 Between 64 and 68 AD | The apostle of Jesus was crucified upside-down in Rome, based on his claim of being unworthy to die in the same way as his Saviour. [38] |

| Simon the Zealot |  |

1 1st century AD | According to an ancient tradition, the apostle of Jesus, was sawn in half in Persia. [39] |

| Saint Lawrence |  |

258 | The deacon was roasted alive on a giant grill during the persecution of Valerian. [40] [41] Prudentius tells that he joked with his tormentors, "Turn me over—I'm done on this side". [42] He is now the patron saint of cooks, chefs, and comedians. [43] |

| Marcus of Arethusa |  |

362 | The Christian bishop and martyr was hung up in a honey-smeared basket for bees to sting him to death. [10]: 104 |

| Valentinian I |  |

17 November 375 | The Roman emperor suffered a stroke which was provoked by yelling at foreign envoys in anger. [44] |

- ^ Hoff, Ursula (1937). "Meditation in Solitude". Journal of the Warburg Institute. 1 (4) (44 ed.): 292–294. doi: 10.2307/749994. JSTOR 749994.

- ^ Elder (1849). "Menes". Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Vol. 2. Boston: Charles C. Little & James Brown..

- ^ Felton, Bruce (1985). "Most Unusual Death". Felton & Fowler's Best, Worst, and Most Unusual. Random House. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-517-46297-3.

- ^ Murray, Alexander (2007). Suicide in the Middle Ages: Volume 2: The Curse on Self-Murder. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-19-820731-3.

- ^ McGlew, James F. (1993). Tyranny and Political Culture in Ancient Greece. Ithaca, New York and London, England: Cornell University Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8014-8387-5.

- ^ Groebner, Valentin (2002). Liquid Assets, Dangerous Gifts: Presents and Politics at the End of the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8122-3650-7.

- ^ Matlock, Brett (2011). The Salt Lake Loonie. University of Regina Press. p. 81.

-

^ Gardiner, EN (1906). "

The Journal of Hellenic Studies". Nature. 124 (3117) (3117 ed.): 121–122.

Bibcode:

1929Natur.124..121..

doi:

10.1038/124121a0.

Fatal accidents did occur as in the case of Arrhichion, but they were very rare...

-

^ Copeland, Cody (10 February 2021).

"The Bizarre Death Of Milo Of Croton".

Grunge.com. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

Milo of Croton's death was bizarre, but fitting

- ^ a b c d e Marvin, Frederic Rowland (1900). The Last Words (Real and Traditional) of Distinguished Men and Women. Troy, New York: C. A. Brewster & Co.

- ^ Burkert, Walter (1972). Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-674-53918-1.

- ^ a b c Simoons, Frederick J. (1998). Plants of Life, Plants of Death. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 225–228. ISBN 978-0-299-15904-7.

- ^ Zhmud, Leonid (2012). Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 137, 200. ISBN 978-0-19-928931-8.

- ^ Fairweather, Janet (1973). "Death of Heraclitus". p. 2. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017.

- ^ Wanley, Nathaniel (1806). "Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths § 6". The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. p. 111. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918.

- ^ a b c Marr, John (October 1995). "The Death of Themistocles". Greece & Rome. 42 (2) (2 ed.): 159–167. doi: 10.1017/S0017383500025614. JSTOR 643228.

-

^ Cite error: The named reference

TI138was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Pliny the Elder. "chapter 3". Naturalis Historiæ. Vol. Book X.

- ^ La tortue d'Eschyle et autres morts stupides de l'Histoire. Editions Les Arènes. 2012. ISBN 978-2352042211.

- ^ a b McKeown, J. C. (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0-19-998210-3.

- ^ Gregory, Andrew (2013). The Presocratics and the Supernatural: Magic, Philosophy and Science in Early Greece. New York City, New York and London, England: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-4725-0416-6.

- ^ Meyer, T. H. (2016). Barefoot Through Burning Lava: On Sicily, the Island of Cain – An Esoteric Travelogue. Temple Lodge Publishing. ISBN 978-1906999940.

- ^ Frater, Jamie (2010). "10 truly bizarre deaths". Listverse.Com's Ultimate Book of Bizarre Lists. Ulysses Press. p. 12–14. ISBN 978-1-56975-817-5.

- ^ J. C. McKeown (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-19-998212-7.

- ^ McKeown, J. C. (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-19-998210-3.

- ^ "Suda α 2735".

- ^ Baldi, Dino (2010). Morti favolose degli antichi (in Italian). Macerata: Quodlibet. p. 50. ISBN 978-8874623372.

- ^ Cameron, Alan (1991). "How thin was Philitas?". The Classical Quarterly. 41 (2) (2 ed.): 534–538. doi: 10.1017/S0009838800004717.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, § 28.

- ^ Wright, David Curtis (2001). The History of China. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-313-30940-3.

- ^ The First Emperor. Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 82, 150. ISBN 978-0-19-152763-0.

- ^ Hopper, Nate (4 February 2013). "Royalty and their Strange Deaths". Esquire. Archived from the original on 2013-11-19.

- ^ Laertius, Diogenes (1965). Lives, Teachings and Sayings of the Eminent Philosophers, with an English translation by R.D. Hicks. Cambridge, Mass/London: Harvard UP/W. Heinemann Ltd.

- ^ "The Funniest And Weirdest Ways People Have Actually Died –". visual.ly. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017.

- ^ Church, Alfred J. (1883). Roman Life in the Days of Cicero. London: Seeley, Jackson, & Halliday.

- ^ Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Tacitus, Annals – Book VI Chapters 28–51". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Cossetta, Erin (12 April 2021). "Here's What An Upside Down Cross Really Means". Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ Il Grande Dizionario dei Santi e dei Beati (in Italian). Vol. 4. Rome: Finegil Editoriale/Federico Motta Editore. 2006. pp. 217–218.

- ^ Catholic Online. "St. Lawrence – Martyr". Archived from the original on 4 January 2018.

- ^ "Saint Lawrence of Rome". CatholicSaints.Info. 26 October 2008. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015.

- ^ Nigel Jonathan Spivey (2001). Enduring Creation: Art, Pain, and Fortitude. University of California Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-520-23022-4.

- ^ Cayne (1981). The Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 17. Grolier. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7172-0112-9.

- ^ Lenski, Noel (2014). Failure of Empire. University of California Press. p. 142.

| Draft article not currently submitted for review.

This is a draft Articles for creation (AfC) submission. It is not currently pending review. While there are no deadlines, abandoned drafts may be deleted after six months. To edit the draft click on the "Edit" tab at the top of the window. To be accepted, a draft should:

It is strongly discouraged to write about yourself, your business or employer. If you do so, you must declare it. Where to get help

How to improve a draft

You can also browse Wikipedia:Featured articles and Wikipedia:Good articles to find examples of Wikipedia's best writing on topics similar to your proposed article. Improving your odds of a speedy review To improve your odds of a faster review, tag your draft with relevant WikiProject tags using the button below. This will let reviewers know a new draft has been submitted in their area of interest. For instance, if you wrote about a female astronomer, you would want to add the Biography, Astronomy, and Women scientists tags. Editor resources

Last edited by

Citation bot (

talk |

contribs) 35 days ago. (

Update) |

Ta lista nietypowych śmierci zawiera niezwykłe lub niesamowicie rzadkie przypadki śmierci zapisane w historii i uznane jako niezwykłe poprzez kilka źródeł.

Antyk

| Imię osoby | Obraz | Data śmierci | Opis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Menes | 3200 BC c. 3200 p.n.e | Egipski Faraon i jednoczyciel Górnego i Dolnego Egiptu został porwany a potem zabity przez hipopotama. [2] | |

| Drakon | 620 BC c. 620 p.n.e. | The Athenian lawmaker was reportedly smothered to death by gifts of cloaks and hats showered upon him by appreciative citizens at a theatre in Aegina, Greece. [3] | |

| Charondas |  |

700 BCc. 612 BC | According to Diodorus Siculus, the Greek lawgiver from Sicily issued a law that anyone who brought weapons into the Assembly must be put to death. One day, he arrived at the Assembly seeking help to defeat some brigands in the countryside, but with a knife still attached to his belt. In order to uphold his own law, he committed suicide. [4] [5] [6] |

| Arrhichion of Phigalia |  |

564 BC | The Greek pankratiast caused his own death during the Olympic finals. Held by his unidentified opponent in a stranglehold and unable to free himself, Arrhichion kicked his opponent, causing him so much pain from a foot/ankle injury that the opponent made the sign of defeat to the umpires, but at the same time broke Arrhichion's neck. Since the opponent had conceded defeat, Arrhichion was proclaimed the victor posthumously. [7] [8] |

| Milo of Croton |  |

600 BC 6th century BC | The Olympic champion wrestler's hands reportedly became trapped when he tried to split a tree apart; he was then devoured by wolves (or, in later versions, lions). [9] |

| Zeuxis |  |

500 BC 5th century BC | The Greek painter died of laughter while painting an elderly woman. [10] |

| Pythagoras of Samos |  |

495 BC c. 495 BC | Ancient sources disagree on how the Greek philosopher died, [11] [12] but one late and probably apocryphal legend reported by both Diogenes Laërtius, a third-century AD biographer of famous philosophers, and Iamblichus, a Neoplatonist philosopher, states that Pythagoras was murdered by his political enemies. Supposedly, he almost managed to outrun them, but he came to a bean field and refused to run through it, as he had prohibited beans as ritually unclean. [12] [13] Since cutting through the field would violate his own teachings, Pythagoras simply stopped running and was killed. This story may have been fabricated by Neanthes of Cyzicus, on whom both Diogenes and Iamblichus rely as a source. [12] |

| Anacreon |  |

485 BC c. 485 BC | The poet, known for works in celebration of wine, choked to death on a grape stone according to Pliny the Elder. The 1911 <i id="mwtQ">Encyclopædia Britannica</i> suggests that "the story has an air of mythical adaptation to the poet's habits". [10]: 104 |

| Heraclitus of Ephesus |  |

475 BC c. 475 BC | According to one account given by Diogenes Laërtius, the Greek philosopher was said to have been devoured by dogs after smearing himself with cow manure in an attempt to cure his dropsy. [14] [15] |

| Themistocles |  |

459 BC c. 459 BC | The Athenian general who won the Battle of Salamis actually died of natural causes in exile, [16] but was widely rumored to have committed suicide by drinking a solution of crushed minerals known as bull's blood. [17] [16] The legend is widely retold in classical sources. The early twentieth-century English classicist Percy Gardner proposed that the story about him drinking bull's blood may have been based on an ignorant misunderstanding of a statue showing Themistocles in a heroic pose, holding a cup as an offering to the gods. The comedic playwright Aristophanes references Themistocles drinking bull's blood in his comedy The Knights (performed in 424 BC) as the most heroic way for a man to die. [16] |

| Aeschylus |  |

455 BC c. 455 BC | According to Valerius Maximus, the eldest of the three great Athenian tragedians was killed by a tortoise dropped by an eagle that had mistaken his bald head for a rock suitable for shattering the shell of the reptile. Pliny the Elder, in his Natural History, adds that Aeschylus had been staying outdoors to avert a prophecy that he would be killed that day "by the fall of a house". [10]: 104 [18] [19] [20] |

| Empedocles of Akragas |  |

430 BC c. 430 BC | According to Diogenes Laërtius, the Pre-Socratic philosopher from Sicily, who, in one of his surviving poems, declared himself to have become a "divine being... no longer mortal", [21] tried to prove he was an immortal god by leaping into Mount Etna, an active volcano. [22] This legend is also alluded to by the Roman poet Horace. |

| Sophocles |  |

406 BC c. 406 BC | A number of "remarkable" legends concerning the death of another of the three great Athenian tragedians are recorded in the late antique Life of Sophocles. According to one legend, he choked to death on an unripe grape. Another says that he died of joy after hearing that his last play had been successful. A third account reports that he died of suffocation, after reading aloud a lengthy monologue from the end of his play Antigone, without pausing to take a breath for punctuation. [20] |

| Mithridates | 401 BC | The Persian soldier who embarrassed his king, Artaxerxes II, by boasting of killing his rival, Cyrus the Younger (who was the brother of Artaxerxes II), was executed by scaphism. The king's physician, Ctesias, reported that Mithridates survived the insect torture for 17 days. [23] [24] | |

| Democritus of Abdera |  |

370 BC c. 370 BC | According to Diogenes Laërtius, the Greek Atomist philosopher died aged 109; as he was on his deathbed, his sister was greatly worried because she needed to fulfill her religious obligations to the goddess Artemis in the approaching three-day Thesmophoria festival. Democritus told her to place a loaf of warm bread under his nose, and was able to survive for the three days of the festival by sniffing it. He died immediately after the festival was over. [25] |

| Antiphanes | 310 BC c. 310 BC | According to the Suda, the renowned comic poet of the Middle Attic comedy died after being struck by a pear. [26] [27] | |

| Agathocles of Syracuse |  |

289 BC | The Greek tyrant of Syracuse was murdered with a poisoned toothpick. [10]: 104 |

| Philitas of Cos |  |

270 BC c. 270 BC | The Greek intellectual is said by Athenaeus to have studied arguments and erroneous word usage so intensely that he wasted away and starved to death. British classicist Alan Cameron speculates that Philitas died from a wasting disease which his contemporaries joked was caused by his pedantry. [28] |

| Zeno of Citium |  |

270 BC c. 262 BC | The Greek philosopher from Citium (Kition), Cyprus, tripped and fell as he was leaving the school, breaking his toe. Striking the ground with his fist, he quoted the line from the Niobe, "I come, I come, why dost thou call for me?" He died on the spot through holding his breath. [29] |

| Qin Shi Huang |  |

August 210 BC | The first emperor of China, whose artifacts and treasures include the Terracotta Army, died after ingesting several pills of mercury, in the belief that it would grant him eternal life. [30] [31] [32] |

| Chrysippus of Soli |  |

206 BC c. 206 BC | One ancient account of the death of the third-century BC Greek Stoic philosopher tells that he died of laughter after he saw a donkey eating his figs; he told a slave to give the donkey neat wine to drink with which to wash them down, and then, "...having laughed too much, he died" (Diogenes Laërtius 7.185). [33] |

| Eleazar Avaran |  |

163 BC c. 163 BC | According to 1 Maccabees 6:46, the brother of Judas Maccabeus thrust his spear in battle into the belly of a king's war elephant, which collapsed and fell on top of Eleazar, killing him instantly. [34] |

| Manius Aquillius and Marcus Licinius Crassus |   |

1 BC 1st Century BC | The late Roman Republic-era consul was sent as ambassador to Asia Minor in 90 BC to restore Nicomedes IV of Bithynia to his kingdom after the latter was expelled by Mithridates VI of Pontus. But Aquillius encouraged Nicomedes to raid part of Mithridates' territory, which started the First Mithridatic War. Aquillius was captured and brought to Mithridates, who in 88 BC had him executed by pouring molten gold down his throat. According to one story, Marcus Licinius Crassus, a Roman general and statesman, who was very greedy despite being called "the richest man in Rome," was executed in the same manner by the Parthians after they defeated him in the Battle of Carrhae in 53 BC, in symbolic mockery of his thirst for wealth. However, it has been disputed as to whether this is how Crassus met his end. |

| Porcia Catonis |  |

June 43 BC June 43 BC to October 42 BC | The daughter of Marcus Porcius Cato Uticensis and second wife of Marcus Junius Brutus, according to ancient historians such as Cassius Dio and Appian, killed herself by swallowing hot coals. Modern historians find this tale implausible. [35] |

| Claudius Drusus |  |

20 c. 20 AD | According to Suetonius, the eldest son of the future Roman emperor Claudius died while playing with a pear. Having tossed the pear high in the air, he caught it in his mouth when it came back, but he choked on it, dying of asphyxia. [36] |

| Tiberius |  |

March 16, 37 | The Roman emperor died in Misenum aged 78. According to Tacitus, the emperor appeared to have died and Caligula, who was at Tiberius' villa, was being congratulated on his succession to the empire, when news arrived that the emperor had revived and was recovering his faculties. Those who had moments before recognized Caligula as Augustus fled in fear of the emperor's wrath, while Macro, a prefect of the Praetorian Guard, took advantage of the chaos to have Tiberius smothered with his own bedclothes, definitively killing him. [37] |

| Simon Peter |  |

1 Between 64 and 68 AD | The apostle of Jesus was crucified upside-down in Rome, based on his claim of being unworthy to die in the same way as his Saviour. [38] |

| Simon the Zealot |  |

1 1st century AD | According to an ancient tradition, the apostle of Jesus, was sawn in half in Persia. [39] |

| Saint Lawrence |  |

258 | The deacon was roasted alive on a giant grill during the persecution of Valerian. [40] [41] Prudentius tells that he joked with his tormentors, "Turn me over—I'm done on this side". [42] He is now the patron saint of cooks, chefs, and comedians. [43] |

| Marcus of Arethusa |  |

362 | The Christian bishop and martyr was hung up in a honey-smeared basket for bees to sting him to death. [10]: 104 |

| Valentinian I |  |

17 November 375 | The Roman emperor suffered a stroke which was provoked by yelling at foreign envoys in anger. [44] |

- ^ Hoff, Ursula (1937). "Meditation in Solitude". Journal of the Warburg Institute. 1 (4) (44 ed.): 292–294. doi: 10.2307/749994. JSTOR 749994.

- ^ Elder (1849). "Menes". Dictionary of Greek and Roman biography and mythology. Vol. 2. Boston: Charles C. Little & James Brown..

- ^ Felton, Bruce (1985). "Most Unusual Death". Felton & Fowler's Best, Worst, and Most Unusual. Random House. p. 161. ISBN 978-0-517-46297-3.

- ^ Murray, Alexander (2007). Suicide in the Middle Ages: Volume 2: The Curse on Self-Murder. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-19-820731-3.

- ^ McGlew, James F. (1993). Tyranny and Political Culture in Ancient Greece. Ithaca, New York and London, England: Cornell University Press. pp. 108–109. ISBN 978-0-8014-8387-5.

- ^ Groebner, Valentin (2002). Liquid Assets, Dangerous Gifts: Presents and Politics at the End of the Middle Ages. The Middle Ages Series. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. p. 131. ISBN 978-0-8122-3650-7.

- ^ Matlock, Brett (2011). The Salt Lake Loonie. University of Regina Press. p. 81.

-

^ Gardiner, EN (1906). "

The Journal of Hellenic Studies". Nature. 124 (3117) (3117 ed.): 121–122.

Bibcode:

1929Natur.124..121..

doi:

10.1038/124121a0.

Fatal accidents did occur as in the case of Arrhichion, but they were very rare...

-

^ Copeland, Cody (10 February 2021).

"The Bizarre Death Of Milo Of Croton".

Grunge.com. Retrieved 3 January 2022.

Milo of Croton's death was bizarre, but fitting

- ^ a b c d e Marvin, Frederic Rowland (1900). The Last Words (Real and Traditional) of Distinguished Men and Women. Troy, New York: C. A. Brewster & Co.

- ^ Burkert, Walter (1972). Lore and Science in Ancient Pythagoreanism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-674-53918-1.

- ^ a b c Simoons, Frederick J. (1998). Plants of Life, Plants of Death. Madison, Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press. pp. 225–228. ISBN 978-0-299-15904-7.

- ^ Zhmud, Leonid (2012). Pythagoras and the Early Pythagoreans. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 137, 200. ISBN 978-0-19-928931-8.

- ^ Fairweather, Janet (1973). "Death of Heraclitus". p. 2. Archived from the original on 6 November 2017.

- ^ Wanley, Nathaniel (1806). "Chapter XXVIII: Of the different and unusual Ways by which some Men have come to their Deaths § 6". The Wonders of the Little World; Or, A General History of Man: Displaying the Various Faculties, Capacities, Powers and Defects of the Human Body and Mind, in Many Thousand Most Interesting Relations of Persons Remarkable for Bodily Perfections or Defects; Collected from the Writings of the Most Approved Historians, Philosophers, and Physicians, of All Ages and Countries - Book I: Which treats of the Perfections, Powers, Capacities, Defects, Imperfections, and Deformities of the Body of Man. Vol. 1 (A new ed.). London. p. 111. LCCN 07003035. OCLC 847968918.

- ^ a b c Marr, John (October 1995). "The Death of Themistocles". Greece & Rome. 42 (2) (2 ed.): 159–167. doi: 10.1017/S0017383500025614. JSTOR 643228.

-

^ Cite error: The named reference

TI138was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ Pliny the Elder. "chapter 3". Naturalis Historiæ. Vol. Book X.

- ^ La tortue d'Eschyle et autres morts stupides de l'Histoire. Editions Les Arènes. 2012. ISBN 978-2352042211.

- ^ a b McKeown, J. C. (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. pp. 136–137. ISBN 978-0-19-998210-3.

- ^ Gregory, Andrew (2013). The Presocratics and the Supernatural: Magic, Philosophy and Science in Early Greece. New York City, New York and London, England: Bloomsbury Academic. p. 178. ISBN 978-1-4725-0416-6.

- ^ Meyer, T. H. (2016). Barefoot Through Burning Lava: On Sicily, the Island of Cain – An Esoteric Travelogue. Temple Lodge Publishing. ISBN 978-1906999940.

- ^ Frater, Jamie (2010). "10 truly bizarre deaths". Listverse.Com's Ultimate Book of Bizarre Lists. Ulysses Press. p. 12–14. ISBN 978-1-56975-817-5.

- ^ J. C. McKeown (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford University Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-19-998212-7.

- ^ McKeown, J. C. (2013). A Cabinet of Greek Curiosities: Strange Tales and Surprising Facts from the Cradle of Western Civilization. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-0-19-998210-3.

- ^ "Suda α 2735".

- ^ Baldi, Dino (2010). Morti favolose degli antichi (in Italian). Macerata: Quodlibet. p. 50. ISBN 978-8874623372.

- ^ Cameron, Alan (1991). "How thin was Philitas?". The Classical Quarterly. 41 (2) (2 ed.): 534–538. doi: 10.1017/S0009838800004717.

- ^ Laërtius 1925, § 28.

- ^ Wright, David Curtis (2001). The History of China. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 49. ISBN 978-0-313-30940-3.

- ^ The First Emperor. Oxford University Press. 2007. p. 82, 150. ISBN 978-0-19-152763-0.

- ^ Hopper, Nate (4 February 2013). "Royalty and their Strange Deaths". Esquire. Archived from the original on 2013-11-19.

- ^ Laertius, Diogenes (1965). Lives, Teachings and Sayings of the Eminent Philosophers, with an English translation by R.D. Hicks. Cambridge, Mass/London: Harvard UP/W. Heinemann Ltd.

- ^ "The Funniest And Weirdest Ways People Have Actually Died –". visual.ly. Archived from the original on 30 April 2017.

- ^ Church, Alfred J. (1883). Roman Life in the Days of Cicero. London: Seeley, Jackson, & Halliday.

- ^ Suetonius Tranquillus, Gaius. The Lives of the Twelve Caesars.

- ^ "LacusCurtius • Tacitus, Annals – Book VI Chapters 28–51". penelope.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- ^ Cossetta, Erin (12 April 2021). "Here's What An Upside Down Cross Really Means". Retrieved 15 August 2021.

- ^ Il Grande Dizionario dei Santi e dei Beati (in Italian). Vol. 4. Rome: Finegil Editoriale/Federico Motta Editore. 2006. pp. 217–218.

- ^ Catholic Online. "St. Lawrence – Martyr". Archived from the original on 4 January 2018.

- ^ "Saint Lawrence of Rome". CatholicSaints.Info. 26 October 2008. Archived from the original on 14 February 2015.

- ^ Nigel Jonathan Spivey (2001). Enduring Creation: Art, Pain, and Fortitude. University of California Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-520-23022-4.

- ^ Cayne (1981). The Encyclopedia Americana. Vol. 17. Grolier. p. 85. ISBN 978-0-7172-0112-9.

- ^ Lenski, Noel (2014). Failure of Empire. University of California Press. p. 142.