From the 1643 edition, published by Francesco Baba. Its position, appended to the end of

De Vita Beata, reflects the manuscript tradition | |

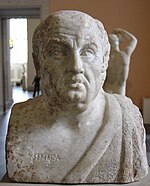

| Author | Lucius Annaeus Seneca |

|---|---|

| Country | Ancient Rome |

| Language | Latin |

| Subject | Ethics |

| Genre | Philosophy |

Publication date | AD c. 62 |

De Otio (On Leisure) is a 1st-century Latin work by Seneca (4 BC–65 AD). It survives in a fragmentary state. The work concerns the rational use of spare time, whereby one can still actively aid humankind by engaging in wider questions about nature and the universe.

Dating

No absolute certainty about the date of writing is possible, but since the contents of the work parallel Seneca's own withdrawal into private life near the end of his life it is thought by a majority of critics to have been written around 62 AD or shortly after. [1] [2]

Title and contents

Otio is from otium, this literally translates as leisure, vacant time, freedom from business. [3]

De Otio survives only in fragmentary form. The manuscript text begins mid-sentence, and ends rather abruptly. [4] [5] In the Codex Ambrosianus C 90 (the main source for Seneca's essays) it is simply tacked onto the end of De Vita Beata suggesting a scribe missed a page or two. [6] The title of the essay, De Otio, is known from the table of contents. The addressee has been erased but appears to have been seven letters long and is assumed to have been Seneca's friend Serenus. [6] De Otio is thus one of a trio of dialogues addressed to Serenus, which also includes De Constantia Sapientis and De Tranquillitate Animi. [7] Chronologically, it is thought to be the last of the three. [7]

Themes

Seneca understood the word otio to represent something more than absolute free-time. He understood it to mean leisure used in service to the community by intellectual activity: [8]

... hoc nempe ab homine exigitur, ut prosit hominibus

... this of course is required of a human, to benefit their fellow humans

In De Otio Seneca debates the appropriate life for a Stoic philosopher. Seneca reports the standard position of the school that wise people will engage in public affairs, unless something prevents them. Seneca lists some arguments against engaging in public life such as if the state is too corrupt, or if the wise person's influence is too limited, or if they are ill. Seneca then shows that private life (otium) far from being a life of listless retirement can be active from a Stoic point of view. The wise person can choose to engage with the wider universe: by moving one's actions from the local to the cosmic perspective and engage with the fundamental questions of the universe, one can still aid all of humankind. [2]

The superior position the sage (ho sophos) inhabits of detachment from earthly (terena) concerns, and an according freedom from possible future events of detrimental nature, is a unifying theme of the dialogue. [9] [7]

References

- ^ G. D. Williams – Lucius Annaeus Seneca – De Otio – Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics (p. 2) (Cambridge University Press, 2003) ISBN 0521588065 [Retrieved 2015-3-16]

- ^ a b R Scott Smith – Brill's Companion to Seneca: Philosopher and Dramatist (edited by Andreas Heil, Gregor Damschen) Brill, 2013 ISBN 9004217088 [Retrieved 2015-3-16]

- ^ Perseus Digital Library – Latin Word Study Tool otium – otio [Retrieved 2015-3-16]

- ^ Howatson, M. (2013). The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. p. 519. ISBN 978-0199548552.

- ^ Bartsch, Shadi; Schiesaro, Alessandro, eds. (2015). The Cambridge Companion to Seneca. p. 79. ISBN 978-1316239896.

- ^ a b Cooper, John M.; Procopé, J. F. (1995). Seneca: Moral and Political Essays. Cambridge University Press. p. 167. ISBN 0521348188.

- ^ a b c Gian Biagio Conte – professor of Latin literature in the Department of Classical Philology at the University of Pisa, Italy. (Translated by J Solodow) (1999). Latin Literature: A History. JHU Press. ISBN 0801862531. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- ^ T E Beck (editor) "Introduction" to B Taegio – La Villa (first published 1559) Penn Studies in Landscape Architecture (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011) ISBN 0812203801 [Retrieved 2015-3-16]

- ^ R Bett – A Companion to Ancient Philosophy p. 531 (edited by Mary Louise Gill, Pierre Pellegrin) [Retrieved 2015-3-19] (ed. Bett was source of term ho sophos)

Further reading

Translations

- G. D. Williams (2003), Seneca – De Otio, De Brevitate Vitae (Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521588065

- Elaine Fantham, Harry M. Hine, James Ker, Gareth D. Williams (2014). Seneca: Hardship and Happiness. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226748332

- Peter J. Anderson (2015), Seneca: Selected Dialogues and Consolations. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 1624663680

External links

-

Works related to

Of Leisure at Wikisource

Works related to

Of Leisure at Wikisource - Seneca's Dialogues, translated by Aubrey Stewart at Standard Ebooks

- De Otio (Latin) (ed. John W. Basore)

From the 1643 edition, published by Francesco Baba. Its position, appended to the end of

De Vita Beata, reflects the manuscript tradition | |

| Author | Lucius Annaeus Seneca |

|---|---|

| Country | Ancient Rome |

| Language | Latin |

| Subject | Ethics |

| Genre | Philosophy |

Publication date | AD c. 62 |

De Otio (On Leisure) is a 1st-century Latin work by Seneca (4 BC–65 AD). It survives in a fragmentary state. The work concerns the rational use of spare time, whereby one can still actively aid humankind by engaging in wider questions about nature and the universe.

Dating

No absolute certainty about the date of writing is possible, but since the contents of the work parallel Seneca's own withdrawal into private life near the end of his life it is thought by a majority of critics to have been written around 62 AD or shortly after. [1] [2]

Title and contents

Otio is from otium, this literally translates as leisure, vacant time, freedom from business. [3]

De Otio survives only in fragmentary form. The manuscript text begins mid-sentence, and ends rather abruptly. [4] [5] In the Codex Ambrosianus C 90 (the main source for Seneca's essays) it is simply tacked onto the end of De Vita Beata suggesting a scribe missed a page or two. [6] The title of the essay, De Otio, is known from the table of contents. The addressee has been erased but appears to have been seven letters long and is assumed to have been Seneca's friend Serenus. [6] De Otio is thus one of a trio of dialogues addressed to Serenus, which also includes De Constantia Sapientis and De Tranquillitate Animi. [7] Chronologically, it is thought to be the last of the three. [7]

Themes

Seneca understood the word otio to represent something more than absolute free-time. He understood it to mean leisure used in service to the community by intellectual activity: [8]

... hoc nempe ab homine exigitur, ut prosit hominibus

... this of course is required of a human, to benefit their fellow humans

In De Otio Seneca debates the appropriate life for a Stoic philosopher. Seneca reports the standard position of the school that wise people will engage in public affairs, unless something prevents them. Seneca lists some arguments against engaging in public life such as if the state is too corrupt, or if the wise person's influence is too limited, or if they are ill. Seneca then shows that private life (otium) far from being a life of listless retirement can be active from a Stoic point of view. The wise person can choose to engage with the wider universe: by moving one's actions from the local to the cosmic perspective and engage with the fundamental questions of the universe, one can still aid all of humankind. [2]

The superior position the sage (ho sophos) inhabits of detachment from earthly (terena) concerns, and an according freedom from possible future events of detrimental nature, is a unifying theme of the dialogue. [9] [7]

References

- ^ G. D. Williams – Lucius Annaeus Seneca – De Otio – Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics (p. 2) (Cambridge University Press, 2003) ISBN 0521588065 [Retrieved 2015-3-16]

- ^ a b R Scott Smith – Brill's Companion to Seneca: Philosopher and Dramatist (edited by Andreas Heil, Gregor Damschen) Brill, 2013 ISBN 9004217088 [Retrieved 2015-3-16]

- ^ Perseus Digital Library – Latin Word Study Tool otium – otio [Retrieved 2015-3-16]

- ^ Howatson, M. (2013). The Oxford Companion to Classical Literature. p. 519. ISBN 978-0199548552.

- ^ Bartsch, Shadi; Schiesaro, Alessandro, eds. (2015). The Cambridge Companion to Seneca. p. 79. ISBN 978-1316239896.

- ^ a b Cooper, John M.; Procopé, J. F. (1995). Seneca: Moral and Political Essays. Cambridge University Press. p. 167. ISBN 0521348188.

- ^ a b c Gian Biagio Conte – professor of Latin literature in the Department of Classical Philology at the University of Pisa, Italy. (Translated by J Solodow) (1999). Latin Literature: A History. JHU Press. ISBN 0801862531. Retrieved 2015-03-19.

- ^ T E Beck (editor) "Introduction" to B Taegio – La Villa (first published 1559) Penn Studies in Landscape Architecture (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011) ISBN 0812203801 [Retrieved 2015-3-16]

- ^ R Bett – A Companion to Ancient Philosophy p. 531 (edited by Mary Louise Gill, Pierre Pellegrin) [Retrieved 2015-3-19] (ed. Bett was source of term ho sophos)

Further reading

Translations

- G. D. Williams (2003), Seneca – De Otio, De Brevitate Vitae (Cambridge Greek and Latin Classics). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521588065

- Elaine Fantham, Harry M. Hine, James Ker, Gareth D. Williams (2014). Seneca: Hardship and Happiness. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226748332

- Peter J. Anderson (2015), Seneca: Selected Dialogues and Consolations. Hackett Publishing. ISBN 1624663680

External links

-

Works related to

Of Leisure at Wikisource

Works related to

Of Leisure at Wikisource - Seneca's Dialogues, translated by Aubrey Stewart at Standard Ebooks

- De Otio (Latin) (ed. John W. Basore)