Daisy Cave, also known as CA-SMI-261, is an archeological site located on San Miguel Island in California. San Miguel Island is the westernmost island in the Channel Islands. [1] The island sits between the Santa Barbara Channel and the Pacific Ocean and is often notably battered by winds all year round, but the Daisy Cave itself provides solace from the weather and has served as an effective shelter time and time again. The cave appears to have multiple archaeological deposits, in which artifacts ranging from the "terminal Pleistocene to the present." [2] San Miguel was once part of a larger 'Superisland,' connected with Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz and Anacapa to make up Santarosae. [3] Santarosae existed as the 'superisland' until as recent as 10,000 years ago, with some estimation. [3]

The first excavations of the Daisy Cave are estimated to have occurred around the early 1900s. [4] These initial excavations are not well documented, nor well executed; therefore, the 1967 excavation led by Charles Rozaire is largely considered to be the first true scientific excavation. Rozaire (curator of archeology at the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History) and his team excavated about 20% of the deposits within the Daisy Cave, but the technology at the time would hardly lend credence to the true age and significance of his findings. Within this first excavation, the remains of about 26 people were found, [2] as well as other various artifacts and remains.

The next excavation would occur in 1985, when Daniel A. Guthrie, Don P. Morris and Pandora E. Snethkamp conducted another, smaller excavation. They would discover "invaluable faunal and artifactal remains," [2] and this was the first time that evidence was dated to be from the Pleistocene, rather than being from the last 3000 years as Rozaire had suggested. The quality of the evidence was invaluable, but the quantity was lacking, these scholars also took the opportunity to correctly date the artifacts that Rozaire had recovered in his excavation back in 1967.

Most recently in 1989, Don P. Morris, S. Hammersmith, and Jon. M Erlandson completed a map of the Daisy Cave and scheduled further site studies and investigations. [4] Erlandson planned investigations for the summers of 1992, 1993, 1994 and 1996. [2] These efforts "completed the stratigraphically controlled excavation of three 50 cm x 100 cm wide test units in the deposits outside the rockshelter and an exploratory sounding extending Rozaire's test pit inside the cave deeper into stratified sediments beneath the cave floor." [2]

The Daisy Cave serves as a time capsule into the lives of Paleo-Indians, Paleo-Coastal peoples, and other maritime populations (ordered sequentially). [2] Each of the relics found in the Daisy Cave provides valuable insight into the lives of the Paleo-Indians and those who came after, as well as the land in which they existed. Artifacts that have been collected included pieces of basketry, various animal fossils, plant remains, shells and stone tools. [4]

Pieces of cordage and basketry from the Holocene (11,700 years ago to the present) have been found in deposits within the Daisy Cave. During Rozaire's 1967 excavation, "over 400 pieces of cordage, clumps of sea grass, and a 13.5 cm x 6 cm piece of a twined sea grass mat or robe" [5] were found deeper within the cave. The most ancient pieces of basketry (basketry is a general term used to describe "baskets, bags, matting, sandals, and other items made with similar techniques and materials,") [5] were discovered in the 1990s and compete in age with some of the oldest fauna remains that have been found so far.

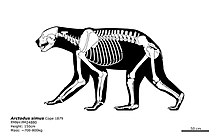

Unlike the mainland of California, an extensive variation of animals is not prevalent. Evidence of dogs, foxes, skunks, birds and mice have been found during the many excavations that have taken place since the early 1900s. [6] Some of the most striking fossil discoveries within the Daisy Cave include those of various rodent species, evidence of the short-faced bear, and remains of two mammoth species.

Much of what has been revealed about the Paleocoastal peoples lies in the discovery of their diets. Exploration of the Daisy Cave has revealed fish bones and 'macrobotanical food remains' [7] that help scholars understand the structure of the Paleocoastal people's lives and adaptations. Because of their location, the early Channel Islanders boasted an impressive ingenuity when it came to harvesting food; they were perhaps the first peoples to utilize hook-and-line fishing, as well as boating. This evidence comes from the analysis of about "27,000 fish bones... dated between about 11,500 and 8500 cal B.P," [8] which suggests that fish and other marine creatures made up more than half of the Islander's diets. From the analysis of these remains, not only did fish make up much of the Islander's diet, but there was also a variety of species that the Islanders fished including: "clupeids, surfperch, rockfish, sheephead, flatfish, elasmobranchs, tunas, and other taxa that are essentially the same types of fish captured by late Holocene and ethnographic people in the area." [8] These various fish bones add to the already established evidence of netting and boat materials to conclude that the Channel Islanders were a population adept at fishing and making the most of their maritime habitat.

Despite the Channel Islands being largely considered as lacking in diverse vegetation, evidence has slowly surfaced that suggests the Islander's also used plants to accompany their largely marine diet. The bulk of this knowledge comes from 16 samples extracted during the 1985-86 excavation conducted by Guthrie, Morris and Snethkamp. The 16 samples "yielded 11 carbonized seeds, 109 fragments of corms and related carbonized remains, and 43 small fragments of manroot." [7] These remains reveal the use of geophytes (geophytes: a perennial plant that bears its perennating buds below the surface of the soil) [9] as a food source, also supported by a high nutrient content that would be effective for Islanders, as well as the sheer amount of these plants that grew back as vegetative populations could recover after overgrazing. [7]

- ^ "Daisy Cave, Santa Barbara Co., California, USA". Minddat.org. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Erlandson, Jon M.; Kennett, Douglas J.; Ingram, B. Lynn; Guthrie, Daniel A.; Morris, Don P.; Tveskov, Mark A.; West, G. James; Walker, Phillip L. (1996). "An Archaeological and Paleontological Chronology for Daisy Cave (CA-SMI-261), San Miguel Island, California". Radiocarbon. 38 (2): 355–373. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200017689. ISSN 0033-8222.

- ^ a b Mychajliw, Alexis M.; Rick, Torben C.; Dagtas, Nihan D.; Erlandson, Jon M.; Culleton, Brendan J.; Kennett, Douglas J.; Buckley, Michael; Hofman, Courtney A. (2020-09-16). "Biogeographic problem-solving reveals the Late Pleistocene translocation of a short-faced bear to the California Channel Islands". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 15172. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71572-z. hdl: 11244/325582. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ a b c "History of Archaeological Research | Natural History Museum". nhm.org. Retrieved 2023-03-07.

- ^ a b Connolly, Thomas J.; Erlandson, Jon M.; Norris, Susan E. (April 1995). "Early Holocene Basketry and Cordage from Daisy Cave San Miguel Island, California". American Antiquity. 60 (2): 309–318. doi: 10.2307/282142. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 282142.

- ^ Shirazi, Sabrina; Rick, Torben C; Erlandson, Jon M; Hofman, Courtney A (May 2018). "A tale of two mice: A trans-Holocene record of Peromyscus nesodytes and Peromyscus maniculatus at Daisy Cave, San Miguel Island, California". The Holocene. 28 (5): 827–833. doi: 10.1177/0959683617744266. ISSN 0959-6836.

- ^ a b c Reddy, Seetha N.; Erlandson, Jon M. (2012-01-01). "Macrobotanical food remains from a trans-Holocene sequence at Daisy Cave (CA-SMI-261), San Miguel Island, California". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (1): 33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2011.07.001. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ a b Rick, Torben C.; Erlandson, Jon M.; Vellanoweth, René L. (October 2001). "Paleocoastal Marine Fishing on the Pacific Coast of the Americas: Perspectives from Daisy Cave, California". American Antiquity. 66 (4): 595–613. doi: 10.2307/2694175. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 2694175.

- ^ "Definition of GEOPHYTE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2023-02-22.

Daisy Cave, also known as CA-SMI-261, is an archeological site located on San Miguel Island in California. San Miguel Island is the westernmost island in the Channel Islands. [1] The island sits between the Santa Barbara Channel and the Pacific Ocean and is often notably battered by winds all year round, but the Daisy Cave itself provides solace from the weather and has served as an effective shelter time and time again. The cave appears to have multiple archaeological deposits, in which artifacts ranging from the "terminal Pleistocene to the present." [2] San Miguel was once part of a larger 'Superisland,' connected with Santa Rosa, Santa Cruz and Anacapa to make up Santarosae. [3] Santarosae existed as the 'superisland' until as recent as 10,000 years ago, with some estimation. [3]

The first excavations of the Daisy Cave are estimated to have occurred around the early 1900s. [4] These initial excavations are not well documented, nor well executed; therefore, the 1967 excavation led by Charles Rozaire is largely considered to be the first true scientific excavation. Rozaire (curator of archeology at the Los Angeles County Museum of Natural History) and his team excavated about 20% of the deposits within the Daisy Cave, but the technology at the time would hardly lend credence to the true age and significance of his findings. Within this first excavation, the remains of about 26 people were found, [2] as well as other various artifacts and remains.

The next excavation would occur in 1985, when Daniel A. Guthrie, Don P. Morris and Pandora E. Snethkamp conducted another, smaller excavation. They would discover "invaluable faunal and artifactal remains," [2] and this was the first time that evidence was dated to be from the Pleistocene, rather than being from the last 3000 years as Rozaire had suggested. The quality of the evidence was invaluable, but the quantity was lacking, these scholars also took the opportunity to correctly date the artifacts that Rozaire had recovered in his excavation back in 1967.

Most recently in 1989, Don P. Morris, S. Hammersmith, and Jon. M Erlandson completed a map of the Daisy Cave and scheduled further site studies and investigations. [4] Erlandson planned investigations for the summers of 1992, 1993, 1994 and 1996. [2] These efforts "completed the stratigraphically controlled excavation of three 50 cm x 100 cm wide test units in the deposits outside the rockshelter and an exploratory sounding extending Rozaire's test pit inside the cave deeper into stratified sediments beneath the cave floor." [2]

The Daisy Cave serves as a time capsule into the lives of Paleo-Indians, Paleo-Coastal peoples, and other maritime populations (ordered sequentially). [2] Each of the relics found in the Daisy Cave provides valuable insight into the lives of the Paleo-Indians and those who came after, as well as the land in which they existed. Artifacts that have been collected included pieces of basketry, various animal fossils, plant remains, shells and stone tools. [4]

Pieces of cordage and basketry from the Holocene (11,700 years ago to the present) have been found in deposits within the Daisy Cave. During Rozaire's 1967 excavation, "over 400 pieces of cordage, clumps of sea grass, and a 13.5 cm x 6 cm piece of a twined sea grass mat or robe" [5] were found deeper within the cave. The most ancient pieces of basketry (basketry is a general term used to describe "baskets, bags, matting, sandals, and other items made with similar techniques and materials,") [5] were discovered in the 1990s and compete in age with some of the oldest fauna remains that have been found so far.

Unlike the mainland of California, an extensive variation of animals is not prevalent. Evidence of dogs, foxes, skunks, birds and mice have been found during the many excavations that have taken place since the early 1900s. [6] Some of the most striking fossil discoveries within the Daisy Cave include those of various rodent species, evidence of the short-faced bear, and remains of two mammoth species.

Much of what has been revealed about the Paleocoastal peoples lies in the discovery of their diets. Exploration of the Daisy Cave has revealed fish bones and 'macrobotanical food remains' [7] that help scholars understand the structure of the Paleocoastal people's lives and adaptations. Because of their location, the early Channel Islanders boasted an impressive ingenuity when it came to harvesting food; they were perhaps the first peoples to utilize hook-and-line fishing, as well as boating. This evidence comes from the analysis of about "27,000 fish bones... dated between about 11,500 and 8500 cal B.P," [8] which suggests that fish and other marine creatures made up more than half of the Islander's diets. From the analysis of these remains, not only did fish make up much of the Islander's diet, but there was also a variety of species that the Islanders fished including: "clupeids, surfperch, rockfish, sheephead, flatfish, elasmobranchs, tunas, and other taxa that are essentially the same types of fish captured by late Holocene and ethnographic people in the area." [8] These various fish bones add to the already established evidence of netting and boat materials to conclude that the Channel Islanders were a population adept at fishing and making the most of their maritime habitat.

Despite the Channel Islands being largely considered as lacking in diverse vegetation, evidence has slowly surfaced that suggests the Islander's also used plants to accompany their largely marine diet. The bulk of this knowledge comes from 16 samples extracted during the 1985-86 excavation conducted by Guthrie, Morris and Snethkamp. The 16 samples "yielded 11 carbonized seeds, 109 fragments of corms and related carbonized remains, and 43 small fragments of manroot." [7] These remains reveal the use of geophytes (geophytes: a perennial plant that bears its perennating buds below the surface of the soil) [9] as a food source, also supported by a high nutrient content that would be effective for Islanders, as well as the sheer amount of these plants that grew back as vegetative populations could recover after overgrazing. [7]

- ^ "Daisy Cave, Santa Barbara Co., California, USA". Minddat.org. Retrieved March 7, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Erlandson, Jon M.; Kennett, Douglas J.; Ingram, B. Lynn; Guthrie, Daniel A.; Morris, Don P.; Tveskov, Mark A.; West, G. James; Walker, Phillip L. (1996). "An Archaeological and Paleontological Chronology for Daisy Cave (CA-SMI-261), San Miguel Island, California". Radiocarbon. 38 (2): 355–373. doi: 10.1017/S0033822200017689. ISSN 0033-8222.

- ^ a b Mychajliw, Alexis M.; Rick, Torben C.; Dagtas, Nihan D.; Erlandson, Jon M.; Culleton, Brendan J.; Kennett, Douglas J.; Buckley, Michael; Hofman, Courtney A. (2020-09-16). "Biogeographic problem-solving reveals the Late Pleistocene translocation of a short-faced bear to the California Channel Islands". Scientific Reports. 10 (1): 15172. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-71572-z. hdl: 11244/325582. ISSN 2045-2322.

- ^ a b c "History of Archaeological Research | Natural History Museum". nhm.org. Retrieved 2023-03-07.

- ^ a b Connolly, Thomas J.; Erlandson, Jon M.; Norris, Susan E. (April 1995). "Early Holocene Basketry and Cordage from Daisy Cave San Miguel Island, California". American Antiquity. 60 (2): 309–318. doi: 10.2307/282142. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 282142.

- ^ Shirazi, Sabrina; Rick, Torben C; Erlandson, Jon M; Hofman, Courtney A (May 2018). "A tale of two mice: A trans-Holocene record of Peromyscus nesodytes and Peromyscus maniculatus at Daisy Cave, San Miguel Island, California". The Holocene. 28 (5): 827–833. doi: 10.1177/0959683617744266. ISSN 0959-6836.

- ^ a b c Reddy, Seetha N.; Erlandson, Jon M. (2012-01-01). "Macrobotanical food remains from a trans-Holocene sequence at Daisy Cave (CA-SMI-261), San Miguel Island, California". Journal of Archaeological Science. 39 (1): 33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2011.07.001. ISSN 0305-4403.

- ^ a b Rick, Torben C.; Erlandson, Jon M.; Vellanoweth, René L. (October 2001). "Paleocoastal Marine Fishing on the Pacific Coast of the Americas: Perspectives from Daisy Cave, California". American Antiquity. 66 (4): 595–613. doi: 10.2307/2694175. ISSN 0002-7316. JSTOR 2694175.

- ^ "Definition of GEOPHYTE". www.merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2023-02-22.