| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Qatar |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Music and Performing arts |

| Sport |

The culture of Qatar is strongly influenced by traditional Bedouin culture, with less acute influence deriving from India, East Africa and elsewhere in the Persian Gulf. The peninsula's harsh climatic conditions compelled its inhabitants to turn to the sea for sustenance. Thus, there is a distinct emphasis placed on the sea in local culture. [1] Literature and folklore themes are often related to sea-based activities.

Oral arts such as poetry and singing were historically more prevalent than figurative art because of the restrictions placed by Islam on depictions of sentient beings; however, certain visual art disciplines such as calligraphy, architecture and textile arts were widely practiced. Figurative arts were gradually assimilated into the country's culture during the oil era. [2]

Cultural policies and affairs are regulated by the Ministry of Culture. The current minister is Abdulrahman bin Hamad bin Jassim bin Hamad Al Thani. [3]

Arts and literature

Visual arts

The modern Qatari art movement emerged in the mid-20th century, facilitated by the newfound wealth from oil exports and subsequent societal modernization. Traditionally, Islamic culture's aversion to depicting sentient beings limited the role of paintings in Qatari society, favoring instead art forms such as calligraphy, architecture, and textiles. [4] However, in the 1950s, the Qatari art scene saw significant development, initially overseen by the Ministry of Education and later supported by increased government funding. Figures like Jassim Zaini, regarded as the father of modern Qatari artists, and Yousef Ahmad played a pivotal role in the transition from traditional to global styles. Institutions like the Qatari Fine Arts Society, established in 1980, and the National Council for Culture, Arts, and Heritage, established in 1998, [5] further propelled the growth of the modern art scene in the country. [6]

Qatar's investments in the arts is exemplified by the establishment of Qatar Museums in the early 2000s, aiming to centralize and connect various museums and collections. [7] Following this was the inauguration of several more major art institutions like the Museum of Islamic Art in 2008, [8] Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in 2010, [9] and the National Museum of Qatar in 2019. [10] Plans for additional museums have been announced, including the Art Mill, Lusail Museum, and Qatar Auto Museum. [11]

For the last twenty years, several members of the Al Thani family have led Qatar's interest and involvement into the field of arts and continue to shape the cultural policy of the country. [12] Qatar was revealed to be the world's biggest art buyer in 2011. [13] Figures like Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad Al Thani, [14] Sheikha Moza bint Nasser and Hassan bin Mohamed Al Thani have played instrumental roles in advancing Qatar's art scene and developing its related institutions. [15]

Architecture

Most traditional houses in the capital Doha were tightly packed and arranged around a central courtyard. A number of rooms were situated in the courtyard, most often including a majilis, bathroom and store room. The houses were made from limestone quarried from local sources. Walls surrounding the compounds were made up of compressed mud, gravel and small stones. As they were heavily susceptible to natural erosion, they were protected by gypsum plaster. Mangrove poles wrapped in jute rope provided structural support for the windows and doors. [16]

Roofs were typically flat and were supported by mangrove poles. The poles were covered with a layer of split bamboo and a palm mat locally called manghrour. The mangrove poles often extended past the exterior walls for decorative purposes. Doors were made of metal or wood. Colored glass employing geometrical designs was sometimes used in windows. [16] The local architecture shows the use of the reddish stone of Qatar, as well as little use of wood due to the scarcity of the resource in the region.

Several methods were used in traditional architecture to alleviate the harsh climate of the country. Windows were seldom used in order to reduce heat conduction. [16] The badgheer construction method allowed air to be channeled into houses for ventilation purposes. This was accomplished by several methods, including horizontal air gaps in rooms and parapets, and vertical openings in wind towers called hawaya which drew air into the courtyards. Wind towers, however, were not as common in Doha as they were in other parts of the country. [17]

Folklore

Qatari folklore is rich with narratives that reflect the cultural heritage of the Persian Gulf region, emphasizing sea-based activities. Known locally as hazzawi, folktales hold significant cultural value, with stories often passed down orally from generation to generation. One such popular myth is that of May and Ghilân. Originating from the Al Muhannadi tribe of Al Khor, the story narrates a struggle between two pearl fishers which results in the creation of the sail. [18] Another tale which carries some popularity locally is the Lord of the Sea, which revolves around a half-man half-fish monster named Bū Daryā who terrorizes sailors. [19]

Among the notable folk heroes in Qatari folklore are individuals like Qatari ibn al-Fuja'a, a celebrated war poet from the 7th century, [20] and Rahmah ibn Jabir Al Jalhami, an infamous pirate and ruler of Qatar in the 18th and 19th centuries. [21] These figures embody themes of heroism, adventure, and resilience that are woven into the fabric of Qatari culture. Recurring motifs in Qatari folklore include djinn, pearl diving, and the sea, often serving as allegories for broader cultural values such as bravery, perseverance, and the importance of community. [19]

With the advent of oil exploration and modernization, the tradition of oral storytelling gradually declined. Efforts by government ministries such as the Ministry of Culture, alongside local universities, have sought to preserve and transcribe these tales in publications. Collaborative endeavors between government agencies, educational institutions, and regional bodies like the GCC States Folklore Centre, headquartered in Doha, have played a crucial role in cataloging and promoting Qatari folklore. [22]

Literature

Qatari literature, originating in the 19th century, has evolved significantly over time, influenced by societal transformations and the nation's economic development. Initially centered around written poetry, literary expression diversified with the introduction of short stories and novels, particularly following the mid-20th-century shift spurred by oil revenues. While poetry, notably the nabati form, remained relevant, other literary genres gained prominence, reflecting changing societal dynamics, including increased female participation in the modern literature movement. [23]

The history of Qatari literature can be broadly categorized into two periods: pre-1950 and post-1950. The latter era witnessed a surge in literary output, fueled by newfound prosperity and expanding educational opportunities. [23] Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani's reign in the late 19th century saw early efforts to fund the printing of Islamic texts, laying the groundwork for literary investments. [24] The modern literature movement gained momentum in the 1950s, paralleling broader cultural shifts and facilitated by improved access to education and globalization. [23]

In terms of modern literature, Qatar saw the popularization of short stories and novels in the 1970s, providing platforms for both male and female writers to explore societal norms and cultural values. Qatari women were as equally involved in the literature movement as the men were, a rarity in Qatar's cultural arenas. [25] Kaltham Jaber became the first Qatari female author to publish a collection of short stories, [26] and to publish a major work when she released her anthology of short stories, dating from 1973 to the year of its publishing, 1978. [27] Novels have become vastly more popular in the 21st century, with nearly a quarter of all existing Qatari-authored novels being published post-2014. [28] Efforts to preserve and document Qatari literature have been undertaken through initiatives like the Qatar Digital Library and the establishment of literary organizations and publishing houses. [29]

Poetry

Poetry has been an integral part of the culture since pre-Islamic times. [30] Qatari ibn al-Fuja'a, a folk hero dating to the seventh-century, was renowned for writing poetry. [31] It was seen as a verbal art which fulfilled essential social functions. Having a renowned poet among its ranks was a source of pride for tribes; it is the primary way in which age-old traditions are passed down generations. Poems composed by females primarily focused on the theme of ritha, to lament. This type of poetry served as an elegy. [30]

Nabati was the primary form of oral poetry. [32] In the nineteenth-century, sheikh Jassim Al Thani composed influential Nabati poems on the political conditions in Qatar. [33] Nabati poems are broadcast on radio and televised in the country. [34]

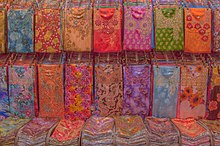

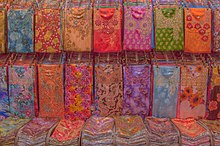

Weaving and dyeing

Weaving and dyeing by women played a substantial role in Bedouin culture. The process of spinning sheep's and camel's wool to produce cloths was laborious. The wool was first disentangled and tied to a bobbin, which would serve as a core and keep the fibers rigid. This was followed by spinning the wool by hand on a spindle known as noul. [35] They were then placed on a vertical loom constructed from wood whereupon women would use a stick to beat the weft into place. [36]

The resulting cloths were used in rugs and carpets and tents. Tents were usually made up of naturally colored cloths, whereas rugs and carpets used dyed cloths; mainly red and yellow. [36] The dyes were fashioned from desert herbs, with simple geometrical designs being employed. The art lost popularity in the 19th century as dyes and cloths were increasingly imported from other regions in Asia. [36]

Embroidery

A simple form of embroidery practiced by Qatari women was known as kurar. It involved four women, each carrying four threads, who would braid the threads on articles of clothing - mainly thawbs or abayas. The braids, varying in color, were sewn vertically. It was similar to heavy chain stitch embroidery. [36] Gold threads, known as zari, were commonly used. They were usually imported from India. [37]

Another type of embroidery involved the designing of caps called gohfiahs. They were made from cotton and were pierced with thorns from palm-trees to allow the women to sew between the holes. This form of embroidery declined in popularity after the country began importing the caps. [37]

Khiyat al madrasa, translated as 'school embroidery', involved the stitching of furnishings by satin stitching. Prior to the stitching process, a shape was drawn onto the fabric by a skilled artist. The most common designs were birds and flowers. [38]

Music

The folk music of Qatar finds its roots in sea folk poetry, deeply influenced by the historical significance of pearl fishing. Traditional dances, such as the ardah and tanbura, are performed during festive occasions such as weddings or feasts and are accompanied by percussion instruments like al-ras and mirwas. Other commonly used types of folk instruments include stringed instruments such as the oud and rebaba, and woodwind instruments like the ney and sirttai. Notably, clapping played a major part in most folk music. [39]

Folk music traditions in Qatar are deeply ingrained in social gatherings like the majlis, where songs and dances are commonplace. Various forms of folk music, including sea songs and urban melodies, continue to thrive today as Khaliji (Gulf) music. Efforts have been made by the Ministry of Culture to preserve and document local folk music, [39] alongside efforts to form an active music scene with the establishment of music institutions like the Qatar Music Academy and the Qatar Philharmonic Orchestra.

Songs related to pearl fishing are the most popular genre of male folk music. Each song, varying in rhythm, narrates a different activity of the pearling trip, including spreading the sails, diving, and rowing the ships. Collective singing was an integral part of each pearling trip, and each ship had a designated singer, known locally as al naham. [40] A specific type of sea music, known as fijiri, originated from sea traditions and features group performances accompanied by melodic singing, rhythmic palm-tapping on water jars (known as galahs), and evocative dances that mimic the movements of the sea waves. [41] Qatari women primarily sang work songs associated with daily activities, such as wheat grinding and cooking, in groups. Public performances by women were practiced only on two annual occasions, the first being al-moradah and the second being al-ashori. [42] Classical Qatari melodies share many similarities with their Gulf conterparts, and most of the same instruments are used. [43]

Traditions

Pearling and fishing

As Qatar is an extremely arid country, [44] the traditional ways of life were confined either to nomadic pastoralism practiced by the Bedouins of the interior and to fishing and pearling, which was engaged in by the relatively settled coastal dwellers. Both fishing and pearling were done mainly using dhows, and the latter activity occasionally employed slaves. Pearling season took place from May to September and the pearls would be exported to Baghdad and elsewhere in Asia. While pearl trading was a lucrative venture for traders and dealers of pearls, the pearlers would receive few of the profits themselves. The main fishing and pearling centers of Qatar throughout its history have been Fuwayrit, Al Huwaila, and Al Bidda. [45]

Pearling is an ancient practice in the Persian Gulf, though it is not known exactly when Arabs began diving for pearls. It has been suggested that the profession dates back to the Dilmun civilization in Bahrain 5,000 years ago, which the inhabitants of Qatar came into contact with at the time. The captain of a pearling craft is called noukhadha, and is responsible for the most important tasks of a pearling trip such as managing interpersonal conflicts between the divers (al-fawwas) and the storage of pearls in the pearling vessel, which is known as al-hairat. The al-muqaddim is responsible for all ship operations while the al-sakuni is the driver of the ship. [46]

Nomadic pastoralism

Bedouin lifestyle was nomadic and consisted of frequent migration, which would come after either a water source had been used up or a grazing site was exhausted. [47] However, in Qatar, most Bedouins would only wander during the winter, as it was too hot to do so during the summer; thus, Qatar was mainly a winter grazing ground for Bedouins from the eastern region of the Arabian Peninsula. Goats and camels were the main livelihoods of Bedouins, with products from the former being used in trade and for sustenance and with camels being used as a means of transportation as well as a source of milk. Every tribe would have its own region, called dirah in Arabic, but if the resources in their dirah had become depleted, then the tribe would be forced to migrate to another tribe's dirah, potentially provoking conflicts. [45]

In the winter when tribes wandered through Qatar, [48] it was unusual for a tribe to remain at one location for a period exceeding ten days. Generally, the average daily distance traveled by Bedouins was not very long, so as to preserve energy and resources. Although the traveling speed would be greatly hastened in cases of inclement weather or far-away distances between one pastureland to another. By and large, it was easier for Bedouin tribes to thrive during the winter months, so long as the rains arrived and there was no in-fighting. Women were responsible for making clothing, taking care of children and preparing food, one popular dish being leben, which comprises fermented milk. Men, on the other hand, would frequently go hunting with hawks and dogs during the winter months. [45]

Leaders of Bedouin tribes, known as sheikhs, often gained their positions by proving themselves to be generous and competent rulers. It was expected of them to provide charity to the poorer members of the tribe should the need arise. The sheikh's wife would be expected to help solve complaints brought to her by the female members of the tribe. Bedouins often lived very modestly, lacking a consistent source of income. Nonetheless, due to the cooperation and charity between tribe members, it was rare that one would go hungry except during exceptionally long droughts. Bedouins of all classes had a reputation for being very hospitable towards guests. [45] After the discovery of oil in Qatar, most Qataris moved to urban areas and the Bedouin way of life gradually disappeared. Only a few tribes in Qatar continue this lifestyle. [49]

Migration patterns

Bedouins inhabiting the regions of north and south Qatar exhibit marked distinctions in their migratory practices, ranging from semi-sedentary lifestyles to frequent nomadism. In northern Qatar, nomads traditionally undertook only brief and sporadic movements. The Al Naim tribe, for instance, spent a considerable portion of the year, approximately six to eight months, at their summer encampments in Al Suwaihliya. Here, they erected stone houses for shelter during the hottest months, alongside their tents used as living and working spaces. Upon the onset of fall, they migrated to Al Jemailiya, where they remained for around three months before proceeding to Murwab for another three months. This cyclical pattern ensured that the Al Naim tribe remained within their tribal territory throughout the year. [50]

The nomadic lifestyle in South Qatar diverged significantly, characterized by heightened mobility and frequent migrations. Utilizing camels as their primary mode of transport, these Bedouins traversed vast sand deserts, often engaging in lengthy migrations into the interior regions. They typically migrated northward during late winter and early spring, drawn by abundant grazing opportunities for their flocks and resources for hunting and truffle-gathering. In contrast, the scorching summer months saw them establish stationary camps near wells to the south of Qatar, congregating in larger groups. Springtime, however, witnessed the formation of smaller, more transient camps. [50]

Tents

Tents (known in Arabic as khaïma) were the primary dwellings of Bedouins, and are still used present-day in the desert. In northern Qatar, the tents displayed a remarkable uniformity in appearance and structure, as well as in their furnishing and use. All sides of the tent were enclosed, ensuring complete privacy within. The interior of the tent comprised distinct sections delineated by woven walls or carpets. During the day, these divisions could be rolled up to create a unified space, swiftly reconfigured when necessary. The sections included quarters for unmarried adult men, designated guest areas, and spaces for children and young animals. Furnishings were modest, typically consisting of beddings, seating mats, and essential utensils. Notably, the central hearth served as a focal point for social gatherings and culinary activities, with water and refreshments readily available. [51]

Women predominantly managed domestic affairs within the tent, including cooking, dairy processing, and crafts such as weaving and sewing. The presence of animals within the tent, particularly during nighttime, led to inevitable accumulation of waste, a common observation in these settings. Remarkably, despite the close relationship with livestock, dogs were notably absent from these camps. [51]

In contrast, camps in southern Qatar typically comprising two to seven tents, were organized around kinship groups and facilitated seasonal migrations for grazing and resource access. The tents, while similar in appearance to those in the north, served as fully functional nomadic dwellings. Fellowship in these Bedouin groups centered around shared labor and communal activities, with a collective emphasis on safeguarding and managing resources, particularly camels. [51]

Livestock rearing

Bedouins have traditionally been reliant on the rearing and grazing of livestock. In the north, despite the tribes there leading more sedentary lives, comprehensive livestock inventories could be found, comprising camels, sheep, goats, a few cows, and donkeys for transportation. Poultry, and occasionally pigeons, were also present. Unlike typical nomadic cultures, Bedouins in Qatar did not utilize dogs for camp guarding, relying instead on salukis for hunting purposes. Camps consisted of 2-6 tents, with livestock keeping influencing their size and cooperative arrangements; a typical tent looking after 30 to 40 animals. Livestock care, primarily the responsibility of men, included tasks such as marking, castration, and slaughtering. Women managed milking and dairy production. Donkeys played a crucial role in transportation and camp activities, while camels were less prominent in the north, primarily housed by select families. [52]

Compared to their northern counterparts, Bedouins in southern Qatar exhibited a more traditional lifestyle, with camels occupying a central role. The Al Murrah tribe, dedicated almost exclusively to camel husbandry, exemplified this tradition. While some groups kept sheep and goats for supplementary purposes, camel herding remained central. [52]

Camels

Camels hold a central position in the lives of desert nomads, particularly among Bedouin tribes. They serve as vital assets for transportation, as well as sources of milk, meat, and various materials. Men primarily oversee breeding and daily care, including tasks like mating, castration, and branding for ownership identification. Women and children also played integral roles in camel care, particularly during migration periods, where they were responsible for loading pack animals and riding camels. Milking is a crucial activity, necessitating the use of udder covers to regulate foal suckling. Training of camels for riding and packing begins at an early age, with specialized saddles employed for different purposes. Equipment for camels includes reins, hobbles, camel sticks for control, and branding irons for marking. [53]

Hunting and scavenging

Hunting is a prominent Bedouin tradition. While wild game was once abundant in Qatar, it had become scarce by the 20th century, with historical accounts recalling hunting with flintlock guns. Bedouins in both the north and south possessed firearms, including rifles and shotguns, but their use for hunting had diminished due to the scarcity of game. In southern Qatar, however, hunting remained more prevalent, with Bedouins equipped with shotguns, rifles, and even falcons, known as wakris. [54]

Falconry was a common pursuit, with falcons trained meticulously for hunting expeditions. Falcons were trained to prey upon hares and other small game, a practice conducted with care and dedication by the falconer. While hunting was esteemed, the scarcity of game meant that falcons were often given priority in obtaining catch. Traps were set for small animals, and falcons were trained to retrieve prey. Hunting hounds, known as salukis, were also occasionally used for hunting to a lesser extent. [54]

In contrast to hunting, collecting activities remained significant, particularly during the truffle season in early spring. Locusts, traditionally valued as food, were gathered during invasions, and natural resources like sea salt were collected from coastal cliffs. Firewood and shrubs were gathered for fuel, though the advent of paraffin stoves reduced the importance of this activity. Collecting extended to salvaging flotsam along the seashores, with timber and planks sought after for various purposes. Additionally, discarded materials from the oil industry and urban areas were systematically collected. [54]

Society and customs

Al-Majlis

A distinctive social tradition among the Persian Gulf people involves communal gatherings at what is known as a majlis, where friends and neighbors convene to discuss matters of mutual interest over cups of Arabic coffee. These gatherings occasionally serve as platforms for various forms of folk arts. In the past, the "dour", or spacious rooms designated for these gatherings, hosted seafarers, dhow captains (noukhadha), and enthusiasts of folk arts between pearl fishing seasons. Here, they engaged in al-samra, evenings of song and dance, celebrated during weddings and other occasions for entertainment. [55]

The majlis also functions as a forum for social interaction, discussion, and conflict resolution, with a particular emphasis on the wisdom and authority of elder members. It serves as a welcoming venue for guests and facilitates social ties. Moreover, the majlis serves an educational function, providing a platform for imparting moral values, etiquette, and life experiences to younger members. [56]

In addition to its social and educational roles, the majlis serves as a form of media, disseminating news, Islamic culture, and literary works through oral storytelling, poetry recitations, and readings of religious texts. It upholds moral standards and etiquette, emphasizing respect for elders, hospitality to guests, and proper conduct during gatherings. The customs and conventions observed in the majlis reflect a broader folk culture characterized by harmony and communal agreement. [56]

The majlis remains a vital component of Qatari society. On 4 December 2015, the majlis was inscribed on UNESCO’s List of Intangible Cultural Heritage in a joint file involving the participation of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, United Arab Emirates, Sultanate of Oman, and Qatar. [57]

Folk beliefs

Folk beliefs in Qatar encompass the various practices rooted in religious and superstitious traditions. Religious beliefs often revolve around rituals and interpretations aimed at averting perceived dangers or invoking divine protection. For instance, the occurrence of an object breaking was interpreted as the removal of evil, while hearing the call to prayer ahead of schedule prompted concerns of impending danger, leading individuals to seek shelter and perform additional prayers. Passing in front of someone engaged in prayer was deemed disrespectful, believed to disrupt the connection between the individual and their deity. [58]

Superstitions permeate various aspects of Qatar's cultural beliefs, with practices aimed at warding off perceived harm or misfortune. Among these, funeral prayers were often recited for individuals believed to harbor envy, accompanied by actions like discreetly sprinkling salt behind their backs to counteract their negative influence. The superstition surrounding open scissors warned of potential discord among family members, prompting swift closure of the shears. Similarly, sleeping on one's back was feared to invite nightmares, attributed to the devil's presence during sleep. Cautionary tales advised against gazing directly at lightning to prevent blindness, while the arrangement of shoes in a reversed position was avoided due to its perceived disrespect towards God. Other taboos included sweeping floors at night, as this would disturb potential djinn residing in homes, and biting one's tongue during meals was interpreted as an ominous sign of impending bad luck. Health-related beliefs were intertwined with practices aimed at maintaining well-being and warding off illnesses. Traditional remedies included consuming specific foods like senna blends or crab meat and shrimp soup, believed to cure various ailments. [58]

Cuisine

Qatari cuisine reflects traditional Arab and Levantine cuisine. [59] It is also heavily influenced by Iranian and Indian cuisine. Seafood and dates are staple food items. [60] As Qatar follows Shariah religious law, alcohol and pork products cannot be brought into the country. [61] Being invited to dine in a Qatari home is considered a special honor, reflecting the cultural value placed on hospitality. One notable aspect of Arab society is the generosity of the host, who typically prepares food in quantities much larger than necessary, ensuring that guests are abundantly provided for. Traditional meals are usually served with guests seated on the floor, partaking of the food with their hands. [62]

Before the meal commences, it is customary to serve coffee or tea. Arabic coffee, brewed in brass coffee pots infused with cardamom, offers a distinctive aroma and flavor. Served in small porcelain cups, guests often consume three to five cups, signaling their satisfaction by gently shaking the cup when they have had their fill. Hot tea, typically flavored with mint and sweetened with sugar, may also be served in small glass mugs. [62]

The main dishes that are considered to be traditional Qatari food, include: [63]

- Machbous (kabsa), which is rice that is cooked with Arabic spices, served with chicken, lamb, or fish. [64] Machbous is mainly served with lamb during big celebrations, and any type of gatherings to show generosity. [65]

- Mathruba, which is rice beaten with cardamom, milk, butter, and any choice of meat, until it turns into porridge form. [64]

- Thareed, consists of bread soaked in vegetable, spices, and chicken/lamb stew. [66] It is specifically served everyday during Ramadan, along with Harees.

- Harees, meat beaten with boiled ground wheat, until it turns into porridge form, to the consistency desired. [67]

- Balaleet, is a sweet and savory dish, that is usually eaten for breakfast or as a dessert, which includes vermicelli cooked with sugar, rose water, cardamom, and saffron, and topped with omelet eggs. [68]

Dress

Clothing laws punish and forbid the wearing of revealing or indecent clothes. [69] The dressing-code law is enforced by a government body called "Al-Adheed". In 2012, a Qatari NGO organized a campaign of "public decency" after they deemed the government to be too lax in monitoring the wearing of revealing clothes; defining the latter as "not covering shoulders and knees, tight or transparent clothes". [69] The campaign targets foreigners who constitute the majority of Qatar's population. [69]

Qatari men wear thawbs (a long white shirt) over loose pants. [70] Aside from protecting the wearer against the dangers of the sun, it also serves as a symbol of affiliation. In previous decades, different types of thawbs were used depending on the occasion, though this is seldom the case now. For instance, the thawb al-nashi is considered the most grand and ornamental type, and was used for celebrations such as weddings, birthdays and family gatherings. Long strips embroidered with beads run down the length of the thawb. It is usually black, but can come in other colors such as blue and red. [71] They also wear a loose headdress, a ghutra, which comes in white or red. [72] Around the ghutra is a black rope called agal, which holds it in place. [70]

Qatari women generally wear customary dresses that include “long black robes” and black head cover hijab, locally called bo'shiya. [73] [74] However, the more traditional Sunni Muslim clothing for women are the black colored body covering known as the abayah together with the black scarf used for covering their heads known as the shayla. [70] A burqa is sometimes worn to conceal their face. [72] It is thought that Qatari women began using face masks in the 19th century amid substantial immigration. As they had no practical ways of concealing their faces from foreigners, they began wearing the same type of face mask as their Persian counterparts. [75] Prior to the age of marriage, girls wear a bukhnoq, an embroidered cloth covering the hair and the upper section of the body. The sleeves are typically designed with local motifs and landscapes. [71]

Jewelry

Jewelry, typically gold-adorned, is very commonly used by Qatari women during special occasions such as weddings. Other pieces of jewelry are designed to be used on a daily basis at home. Most jewelry worn by Qatari women are handmade, even after the rise in popularity of more cost-efficient manufactured jewelry. [76]

Earrings are common pieces of jewelry seen, varying in size from 10 cm to several millimeters. A popular practice involves affixing a short chain, called dalayah, to the earring with a pearl or precious gem attached to the bottom of the chain. Necklaces vary in length, with some being waist-length and others extending only to the top of the neck. Some are highly ornamental, having a pearl attached to the chain which is called maarah, while others use only simple beads. Perhaps the most common piece of jewelry is the mdhaed, or fine bracelets. More than one is typically worn, some times numbering to over a dozen. Other types of bracelets exist, the miltafah being two plaited cables, while others consist only of colored beads, with the occasional golden one. Rings are often worn multiple at a time, with a popular trend being to connect four rings, each to be worn on their corresponding finger, together with a chain, which may also be attached to the woman's bracelets, if worn. [76]

Language

The legitimate language spoken in Qatar is Arabic. [77] However, since more than half of Qatar's population are expats and migrants, English is also commonly spoken at public places especially at shops and restaurants. [78]

The table below includes basic Arabic words: [79]

| Arabic | Arabic (pronunciation) | English |

|---|---|---|

| السلام عليكم | Alsalam-alaykum | Hello |

| وعليكم السلام | Wa-alaykum alsalam | Hello (in response) |

| مرحبا | Marhaba | Welcome |

| كيف حالك | Kaif halak | How are you? |

| بخير | Bkhair | I'm fine |

| لو سمحت | Law samahit | Please/Excuse me |

| مع السلامه | Ma'al-salama | Goodbye |

| شكرا | Shukran | Thank you |

Religion

The state religion in Qatar is Islam. [80] Most Qataris belong to the Sunni sect of Islam. [81] [82] [83] Shiites comprise around 10% of Qatar's Muslim population. [84] Religious policy is set by the Ministry of Islamic Affairs and Islamic instruction is compulsory for Muslims in all state-sponsored schools. [80]

The community is made up of Sunni and Shi’a Muslims, Christians, Hindus, and small groups of Buddhists and Baha’is. [85] Muslims form 65.5% of the Qatari population, followed by Christians at 15.4%, Hindus at 14.2%, Buddhists at 3.3% and the rest 1.9% of the population follow other religions or are unaffiliated. Qatar is also home to numerous other religions mostly from the Middle East and Asia. [86]

Holidays

Qatar's weekends are Friday and Saturday. [87] Qatar National Day was changed from 3 September to 18 December in 2008. [88]

Garangao is a traditional celebration observed on the 15th night of Ramadan, marking its midpoint. Rooted in the Islamic calendar, the festival is derived from the Arabic word "garqaa," signifying a rattling or shaking motion. Celebrated throughout the Middle East, Garangao holds cultural and historical significance in the region. On Garangao night, children don colorful traditional attire and visit homes in their neighborhoods, singing traditional songs and receiving sweets and gifts from residents. This exchange symbolizes the spirit of generosity central to the holy month of Ramadan. The festival is also characterized by unique songs sung by children, invoking blessings for health and prosperity upon the youngest members of families. In contemporary times, Garangao has evolved into a larger-scale celebration, with public events organized in shopping malls, mosques, and cultural organizations. [89]

Notable holidays in the country are listed below:

| Date | English name | Local ( Arabic) name | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Second Tuesday in February | National Sports Day | اليوم الوطني للرياضة | A public holiday. |

| Early March | March bank holiday | عطلة البنك | A bank holiday. |

| 18 December | Qatar National Day | اليوم الوطني لقطر | National Day of Qatar. |

| 1st, 2nd, 3rd Shawwal | Eid ul-Fitr | عيد الفطر | Commemorates end of Ramadan. |

| 10th, 11th, 12th Zulhijjah | Eid ul-Adha | عيد الأضحى | Commemorates

Ibrahim's willingness to sacrifice his son. Also known as the Big Feast (celebrated from the 10th to 13th). |

Sports and recreation

Football is the most popular sport in regards to registered player base. [90] Additionally, athletics, basketball, handball, volleyball, camel racing, horse racing, falconry, cricket and swimming are widely practiced. [91] [92] There are currently 11 multi-sports clubs in the country, and 7 single-sports clubs. [90] Qatar hosted the 2022 FIFA World Cup and is the first Arab nation to have done so. [93]

Historically camel racing was a tradition among the Bedouin tribes of Qatar and would be performed on special occasions such as weddings. [94] It was not until 1972, one year after Qatar's independence, that camel racing was practiced on a professional level. Typically, camel racing season takes place from September to March. [95] Approximately 22,000 racing camels are used in competitions which are mainly held at the country's primary camel racing venue, the Al-Shahaniya Camel Racetrack. The average distance of such races is usually 4 to 8 km depending on the conditions of the camels being raced. [96]

Falconry is widely practiced by Qataris. [97] The only falconry association is Al Gannas, which was founded in 2008 in the Katara Cultural Village and which hosts the Annual Falconry Festival. [98] Hunting season extends from October to April. Prices of falcons can be extremely high, being as expensive as QR 1 million. [99] Saluki dogs are also used for hunting in the desert primarily because of their great speeds. [100] Their main prey in the desert are gazelles and rabbits. [101]

Folk games

Prior to the introduction of football, children played traditional games, including al dahroi, al sabbah, and taq taq taqiyyah for boys, and al kunatb, al laqfah and nat al habl for girls. [102] Variations of a family of board games known as mancala were played in previous decades. [103] Two of the most popular board games were a’ailah and al haluwsah. [102]

Folk games form an important part of Qatar's cultural fabric. Depending on the location, a game could either be a sea game or an urban game; furthermore, most games were gender exclusive. Typically, boys' games would be more physical. One such game was called tnumba, in which two teams would attempt to redirect an airborne ball towards the others' hand-dug pit, which served as a goal. Another similar game was called matoua, and involved taking turns to use a makeshift tennis racket to keep a ball suspended in the air, the winner being that who can keep it in the air for the longest period of time. Farrarah was the name used for a gyroscope which boys would often compete with each other over the length of time they could keep it spinning for. All of these are catgorized as urban games. An example of a sea game, which was less common, was releasing hand-made miniature boats into the water and racing them to a prespecified landmark. The game relied mostly on luck and wind conditions. [104]

Shakaha was a popular girls' game. It involved two girls prone on the ground oriented towards each other, with a third girl attempting to pass by jumping over them. As the game progressed, the girls on the ground would become increasingly outstretched, making it more difficult for the third girl to pass. One game shared by both boys and girls was called zlalwah, and involved the person whose turn it is throwing a stone at the shadow of one of the participants, with the game ending once the targeted person chases and catches one of the others. [104]

Media

There are currently seven newspapers in circulation in Qatar, with four being published in Arabic and three being published in English. [105] Additionally, there are nine magazines. [106]

All radio programmes from Qatar are state-owned and are amalgamated as the Qatar Broadcasting Service. [107] Radio broadcasting in the country began in June 1968 and English transmissions started in December 1971 [108] in order to accommodate the increasing non-Arabic speaking expat community. [109] [110] The QBS currently features radio stations in English, Arabic, French and Urdu. [111]

Al Jazeera, currently Qatar's largest television network, was founded in 1996 and has since become the foundation of the media sector. [112] Initially launched as an Arabic news and current affairs satellite TV channel, Al Jazeera has since expanded into a network with several outlets, including the internet and specialty TV channels in multiple languages. The ' Al Jazeera effect' refers to the global impact of the Al Jazeera Media Network, particularly on the politics of the Arab world. [113]

Cinema

Cinema in Qatar has emerged as a significant cultural and economic force, spurred by initiatives outlined in the Qatar National Vision 2030. The vision's emphasis on human and social development includes a strong commitment to nurturing artistic talents and promoting Qatar's global presence through the film industry. [114] Sheikha Al Mayassa's founding of the Doha Film Institute (DFI) has been pivotal in providing funding, production services, and educational programs to support local and international filmmakers. Through grants, workshops, and festivals, the DFI has facilitated the growth of the local film community. [115]

The Doha Tribeca Film Festival (DTFF) and Ajyal Film Festival are key events that showcase and celebrate cinematic achievements, providing platforms for regional and local talents to exhibit their work. [116] Ajyal, in particular, focuses on engaging audiences in film-centric dialogues and cultivating young talents through volunteering opportunities and youth-focused programs. [117] Additionally, Qumra, a part of the DFI, offers mentorship opportunities and development services for aspiring filmmakers. The establishment of production houses like The Film House and Innovation Films, along with the emergence of notable Qatari directors and filmmakers such as Ahmed Al-Baker and Al Jawhara Al-Thani, have helped advance Qatar's position as a regional film hub.

Television

The multinational media conglomerate Al Jazeera Media Network is based in Doha [118] with its wide variety of channels of which Al Jazeera Arabic, Al Jazeera English, Al Jazeera Documentary Channel, Al Jazeera Mubasher, beIN Sports Arabia and AlrayyanTV with other operations are based in the TV Roundabout in the city.

- Terrestrial television

Terrestrial television stations now available on Nilesat include:

| Channel | Signal | Format | Station name | Network | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 21 | UHF | DVB-T2 | Q Channel Arabia | Lippo Middle East Group | Local / national |

| 31 | Al Watania TV | Lippo Middle East Group | |||

| 37 | MBC 1 MBC 4 MBC Action SportOne TV |

VIVA | |||

| 39 | Fox ME TV Fox News Arabia Sky News Arabia BBC Arabia CNBC CNN CNTV Arabia (Prabowo Saudia TV) |

EMTEK | |||

| 41 | LBC Sat CoopTV Infinity TV (Prabowo Saudia TV) |

EMTEK | |||

| 43 | ITV 1 ITV 2 Brinklow Meridian |

ITV Arabia Group | |||

| 45 | Al Jazeera | Al Jazeera Media Network | |||

| 47 | OSN First More OSN News Al Yawm Series Channel Pesona HD Inspirasi HD Hidayah HD Emas HD Bintang Tara Pelangi Kiara |

OSN MEDIA | |||

| 49 | Radar TV MNC Sports 1 MNC Sports 2 Sport 24 Russia Today France 24 NHK World Premium |

JPMC | Local | ||

| 51 | I-TV I-Music I-Movies Swara Channel GMA Pinoy TV GMA Life TV GMA News TV International |

City TV GMA Network | |||

| 53 | Qatar TV 1 Qatar TV 2 Qatar Airways Interactive Info |

Q MEDIA | |||

| 55 | Colors Sony TV Garuda TV |

VIACOM TV18 | |||

| 57 | Zee TV Zee Alwan STAR Plus O Channel RTVM KSA 1 RTVM KSA 2 |

Zee Network | |||

| 59 | Ajman TV Infinity TV Noor Dubai TV Al Rayyan TV MDC TV (SINDOtv) DMC TV Elshinta TV Jawa Pos TV |

Etisalat JPMC |

See also

References

- ^ Abu Saud, Abeer (1984). Qatari Women: Past and Present. Longman Group United Kingdom. p. 133. ISBN 978-0582783720.

- ^ Abu Saud (1984), p. 134

- ^ "Minister of Culture opens 'Saber' exhibition at Qatar Photography Center". thepeninsulaqatar.com. 2023-02-07. Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ^ Abu Saud (1984), p. 140

- ^ "Culture & Arts". Consulate General of the State of Qatar. Archived from the original on 10 February 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ Abu Saud (1984), p. 142

- ^ Ouroussoff, Nicolai (2010-11-27). "Building Museums, and a Fresh Arab Identity (Published 2010)". The New York Times. Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ^ "Qatar unveils Islamic arts museum". Al Jazeera. 23 November 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ John Zarobell (2017). Art and the Global Economy. University of California Press. p. 165. ISBN 9780520291539.

- ^ Joanne Martin (28 March 2019). "The Middle East's hottest new museum is here". CNN. Retrieved 12 August 2019.

- ^ "Qatar Reveals Ambitious Plans for Three New Cultural Institutions". www.artforum.com. 2022-03-28. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ Robert Kluijver. "The Al Thani's involvement in the arts". Gulf Art Guide. Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Qatar becomes world's biggest buyer of contemporary art". The Guardian. 13 July 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "HE Sheikha Al Mayassa Al Thani, Chairperson of Qatar Museums, is the Guest Editor of the November 2022 Issue of Vogue Arabia". Vogue Arabia. 2022-11-01. Retrieved 2022-12-02.

- ^ "The Al Thani's involvement in the arts". Archived from the original on 18 May 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2015.

- ^ a b c "Traditional domestic architecture of Qatar". Origins of Doha. 15 February 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ "Gulf architecture". catnaps.org. Retrieved 21 July 2015.

- ^ Anie Montigny (2004). "La légende de May et Ghilân, mythe d'origine de la pêche des perles ?". Techniques & Culture (in French) (43–44): 43–44. doi: 10.4000/tc.1161. Retrieved 21 August 2018.

- ^ a b Katarzyna Pechcin (2017). "A Tale of "The Lord of the Sea" in Qatari Folklore and Tradition". Fictional Beings in Middle East Cultures. University of Bucharest's Center for Arab Studies. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ "نبذة حول الشاعر: قطري بن الفجاءة" (in Arabic). Adab. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Allen J. Fromherz (1 June 2017). Qatar: A Modern History, Updated Edition. Georgetown University Press. p. 49. ISBN 9781626164901.

- ^ Amanda Erickson (28 March 2011). "Saving the stories". Christian Science Monitor. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ a b c Hassan Tawfiq (1 May 2015). الشعر في قطر علي امتداد مائة سنة (in Arabic). Al Jasra Cultural and Social Club. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ "His love of Knowledge and Scholars". Qatar Cultural and Heritage Events Center. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ Rebecca L. Torstrick; Elizabeth Faier (2009). Culture and Customs of the Arab Gulf States. Greenwood. p. 49. ISBN 978-0313336591.

- ^ ﻨﻈﻤﻬﺎ إدارة "اﻟﺒﺤﻮث واﻟﺪراﺳﺎت" ﻧﺪوة ﺛﻘﺎﻓﻴﺔ ﺗﻮﺛﻖ ﻟﻠﺴﺮد اﻟﻘﻄﺮي ﻧﻬﺎﻳﺔ أﻛﺘﻮﺑﺮ (in Arabic). Al Sharq. 14 October 2015. Retrieved 23 July 2017 – via PressReader.

- ^ Abu Saud (1984), p. 161

- ^ Mohammed Mostafa Salem (1 August 2017). "22". In Waïl S. Hassan (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of Arab Novelistic Traditions. Oxford University Press. pp. 383–393. ISBN 9780199349807.

- ^ Nadine El-Sayed (11 November 2014). "Digitizing 1,000 years of Gulf history: The Qatar Digital Library opens up the rich history of the Gulf region to the public". Nature Middle East. doi: 10.1038/nmiddleeast.2014.264.

- ^ a b Abu Saud (1984), p. 152

- ^ نبذة حول الشاعر: قطري بن الفجاءة (in Arabic). Adab. Archived from the original on 8 June 2019. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ^ "Poems from the desert dwellers". Arab News. 2009-10-08. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ Abu Saud (1984), p. 154

- ^ Abu Saud (1984), p. 156

- ^ Abu Saud 1984, p. 135

- ^ a b c d Abu Saud 1984, p. 136

- ^ a b Abu Saud 1984, p. 137

- ^ Abu Saud 1984, p. 140

- ^ a b Zyarah, Khaled (1997). Gulf Folk Arts. Translated by Bishtawi, K. Doha: Al-Ahleir Press. pp. 35–37.

- ^ Abu Saud (1984), p. 146

- ^ Zyarah, Khaled (1997). Gulf Folk Arts. Translated by Bishtawi, K. Doha: Al-Ahleir Press. pp. 19–23.

- ^ Abu Saud (1984), p. 147

- ^ Al-Duwayk, Muhammad Talib (1991). Al-ughniya al-sha biyya f Qatar. 2 vols (in Arabic). Vol. 2. Doha: Ministry of Information and Culture. p. 126.

- ^ "Qatar Main Details". www.cbd.int. Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ^ a b c d Rickman, Maureen (1987). "Qatar". New York, NY: Chelsa House. pp. 12–30.

- ^ Al-Duwayk, Muhammad Talib (1991). Al-ughniya al-sha biyya f Qatar. 2 vols (in Arabic). Vol. 2. Doha: Ministry of Information and Culture. p. 15–17.

- ^ Mohammad, T.; Xue, Y.; Evison, M.; Tyler-Smith, C. (2009-07-29). "Genetic structure of nomadic Bedouin from Kuwait". Heredity. 103 (5): 425–433. doi: 10.1038/hdy.2009.72. ISSN 1365-2540. PMC 2869035. PMID 19639002. S2CID 13935301.

- ^ Al-Hammadi, Mariam I. (2018-10-25). "Presentation of Qatari Identity at National Museum of Qatar: Between Imagination and Reality". Journal of Conservation and Museum Studies. 16 (1): 3. doi: 10.5334/jcms.171. ISSN 1364-0429.

- ^ Rickman, Maureen (1987). "Qatar". New York, NY: Chelsa House. p. 50.

- ^ a b Ferdinand, Klaus; Carlsberg Foundation's Nomad Research Project (1993). Bedouins of Qatar. Thames & Hudson. p. 59. ISBN 978-0500015735.

- ^ a b c Ferdinand, Klaus; Carlsberg Foundation's Nomad Research Project (1993). Bedouins of Qatar. Thames & Hudson. p. 98–123. ISBN 978-0500015735.

- ^ a b Ferdinand, Klaus; Carlsberg Foundation's Nomad Research Project (1993). Bedouins of Qatar. Thames & Hudson. p. 60–63. ISBN 978-0500015735.

- ^ Ferdinand, Klaus; Carlsberg Foundation's Nomad Research Project (1993). Bedouins of Qatar. Thames & Hudson. p. 64–74. ISBN 978-0500015735.

- ^ a b c Ferdinand, Klaus; Carlsberg Foundation's Nomad Research Project (1993). Bedouins of Qatar. Thames & Hudson. p. 74–78. ISBN 978-0500015735.

- ^ Zyarah, Khaled (1997). Gulf Folk Arts. Translated by Bishtawi, K. Doha: Al-Ahleir Press. pp. 19–23.

- ^ a b Al-Muhannadi, Hamad. "Chapter 9: The Traditional Roles of al-Majlis" (PDF). Studies in Qatari Folklore. Vol. 2. Heritage Department of the Ministry of Culture and Sports (Qatar). pp. 155–160.

- ^ "UNESCO - Majlis, a cultural and social space".

- ^ a b Basheer, Huda. "Chapter 6: The Role of Kindergartens in Suffusing Tradition in the Minds of Qatari Children" (PDF). Studies in Qatari Folklore. Vol. 2. Translated by El Omrani, Abdelouadoud. Heritage Department of the Ministry of Culture and Sports (Qatar). p. 125–128.

- ^ "The 3 M's of Qatari Cuisine". The Daily Meal. 3 October 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "Culture of Qatar". Hilal Plaza. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- ^ "Qatar - Department of Foreign Affairs". www.dfa.ie. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ^ a b Augustin, Byron; Augustin, Rebecca A. (1 January 1997). Qatar. Enchantment of the World Second Series. New York: Children's Press. pp. 92–93.

- ^ "Qatar World Cup 2022: Seven foods that are distinctly Qatari". Middle East Eye. 2022-10-20. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ^ a b Koduru, Keertana (December 2017). "10 Traditional Qatari Dishes Everyone Must Try". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ Koduru, Keertana (December 2017). "10 Traditional Qatari Dishes Everyone Must Try". Culture Trip. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ^ ansari, hina (2015-07-06). "Ramadan Recipe "Thareed"". Qatar Living. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ^ Almeer, Sheikha Ahmad (2016). The Art of Qatari Cuisine. Doha: Gulf Publishing and Printing Co.

- ^ "Balaleet (Sweet Vermicelli and Eggs)". SAVEUR. 18 March 2019. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ^ a b c "Organizers are calling this campaign "One of Us" - not "No Nudity"". Doha News. Archived from the original on 13 June 2012. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ^ a b c "The Culture of Qatar". HilalPlaza. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ a b Zyarah, Khaled (1997). Gulf Folk Arts. Translated by Bishtawi, K. Doha: Al-Ahleir Press. pp. 44–45.

- ^ a b "Qatar culture". Weill Cornell Medical College in Qatar. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Abu Saud (1984), p. 39

- ^ Courtney King (11 April 2003). "For Qatari Women, Change Slow in Coming". ABC News. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Abu Saud (1984), p. 52

- ^ a b Zyarah, Khaled (1997). Gulf Folk Arts. Translated by Bishtawi, K. Doha: Al-Ahleir Press. pp. 47–50.

- ^ wasim, Saleh (2022-06-14). "What Languages are Spoken in Qatar?". Qatar Just. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ^ "Qatar Culture | Weill Cornell Medicine - Qatar". qatar-weill.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-08.

- ^ "Qatar Culture | Weill Cornell Medicine - Qatar". qatar-weill.cornell.edu. Retrieved 2019-04-09.

- ^ a b US State Dept 2022 report

- ^ "Tiny Qatar's growing global clout". BBC. 30 April 2011. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Qatar's modern future rubs up against conservative traditions". Reuters. 27 September 2012.

- ^ "Rising power Qatar stirs unease among some Mideast neighbors". Reuters. 12 February 2013. Retrieved 13 June 2013.

- ^ "Mapping the Global Muslim Population" (PDF). Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. October 2009. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- ^ "Qatar". rpl.hds.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2023-05-25.

- ^ "Religious Composition by Country" (PDF). Global Religious Landscape. Pew Forum. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- ^ "Public Holidays in Qatar in 2015". Office Holidays. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ "National Day Observances". Timeanddate.com. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Fatemeh Salari (20 March 2024). "What is Garangao and where to celebrate it in Qatar". Doha News. Retrieved 27 April 2024.

- ^ a b "Sports chapter (2013)". Qatar Statistics Authority. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 15 March 2015.

- ^ McManus, John; Al-Dabbagh, Iman (2022-03-20). "Qatar's Most Popular Sport Isn't What You Think It Is". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ "Traditional sports". Qatar Tourism Authority. Archived from the original on 2 May 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2015.

- ^ "Qatar becomes first Arab host of the FIFA World Cup". Retrieved 2023-02-09.

- ^ Breulmann, Marc; Böer, Benno; Wernery, Ulrich; Wernery, Renate; El Shaer, Hassan; Alhadrami, Ghaleb; Gallacher, David; Peacock, John; Chaudhary, Shaukat Ali; Brown, Gary & Norton, John. "The Camel From Tradition to Modern Times" (PDF). UNESCO. Retrieved 23 August 2018.: 25

- ^ "Discovering Traditional Sports - Camel Racing". qlevents.qaactivities. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ^ David Harding (1 May 2017). "Qatar's prized racing camels bred for success". thenational.ae. Agence France-Presse. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Schaff, Erin; Goldbaum, Christina (2022-12-15). "Falconry is an Ancient Sport. In Qatar, Drones Give it a Twist". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2023-01-17.

- ^ "Qatar Maintains Commitment to Falconry as a World Heritage". www.qna.org.qa. 2020-12-04. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ^ "Falconry: A National Sport". Marhaba. 20 September 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- ^ Hecke, Lizette van (2009-08-16). "Hunting with hounds: salukis could be a Bedouin's best friend". The National. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ^ Matthew Cassel (29 January 2012). "In Pictures: Qatar's hunting games". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 26 August 2018.

- ^ a b "Society 2 of 6". Catnaps. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- ^ Igwe, Eleanor (2019-03-03). "LOYAL NANA - The History of Mancala". LOYAL NANA. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

- ^ a b Zyarah, Khaled (1997). Gulf Folk Arts. Translated by Bishtawi, K. Doha: Al-Ahleir Press. pp. 53–58.

- ^ The Report: Qatar 2010. Oxford Business Group. 2010. p. 237. ISBN 9781907065446.

- ^ "IREX Report 2009" (PDF). irex.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 January 2012. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Qatar Country Study Guide Volume 1 Strategic Information and Developments. Int'l Business Publications, USA. 2012. p. 196. ISBN 978-0739762141.

- ^ "QBS FM Radio - Doha". tunein.com. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ "Radio". qmediame.com. Archived from the original on 20 January 2015. Retrieved 20 January 2015.

- ^ Kadhim, Abbas (2013). Governance in the Middle East and North Africa: A Handbook. Routledge. p. 273. ISBN 978-1857435849.

- ^ "Information and Media". qatarembassy.net. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 19 January 2015.

- ^ The Report: Qatar 2009. Oxford Business Group. 2009. p. 200. ISBN 978-1902339252.

- ^ "The 'al-Jazeera Effect': - The Washington Institute for Near East Policy". Washingtoninstitute.org. 2000-12-08. Retrieved 2012-10-24.

- ^ "Qatar National Vision 2030". Government Communications Office. Retrieved 21 April 2019.

- ^ "Press | Doha Film Institute". www.dohafilminstitute.com. Retrieved 2023-02-10.

- ^ "Doha Tribeca Film Festival - Full of Eastern promise". The Independent. 2009-11-06. Retrieved 2023-02-02.

- ^ "Made in Qatar opens at Ajyal Film Festival at Lusail's Drive-In Cinema". thepeninsulaqatar.com. 2020-11-21. Retrieved 2023-04-23.

- ^ "Who we are". Al Jazeera Media Network. Retrieved 2023-01-18.

| Part of a series on the |

| Culture of Qatar |

|---|

|

| History |

| People |

| Languages |

| Cuisine |

| Religion |

| Music and Performing arts |

| Sport |

The culture of Qatar is strongly influenced by traditional Bedouin culture, with less acute influence deriving from India, East Africa and elsewhere in the Persian Gulf. The peninsula's harsh climatic conditions compelled its inhabitants to turn to the sea for sustenance. Thus, there is a distinct emphasis placed on the sea in local culture. [1] Literature and folklore themes are often related to sea-based activities.

Oral arts such as poetry and singing were historically more prevalent than figurative art because of the restrictions placed by Islam on depictions of sentient beings; however, certain visual art disciplines such as calligraphy, architecture and textile arts were widely practiced. Figurative arts were gradually assimilated into the country's culture during the oil era. [2]

Cultural policies and affairs are regulated by the Ministry of Culture. The current minister is Abdulrahman bin Hamad bin Jassim bin Hamad Al Thani. [3]

Arts and literature

Visual arts

The modern Qatari art movement emerged in the mid-20th century, facilitated by the newfound wealth from oil exports and subsequent societal modernization. Traditionally, Islamic culture's aversion to depicting sentient beings limited the role of paintings in Qatari society, favoring instead art forms such as calligraphy, architecture, and textiles. [4] However, in the 1950s, the Qatari art scene saw significant development, initially overseen by the Ministry of Education and later supported by increased government funding. Figures like Jassim Zaini, regarded as the father of modern Qatari artists, and Yousef Ahmad played a pivotal role in the transition from traditional to global styles. Institutions like the Qatari Fine Arts Society, established in 1980, and the National Council for Culture, Arts, and Heritage, established in 1998, [5] further propelled the growth of the modern art scene in the country. [6]

Qatar's investments in the arts is exemplified by the establishment of Qatar Museums in the early 2000s, aiming to centralize and connect various museums and collections. [7] Following this was the inauguration of several more major art institutions like the Museum of Islamic Art in 2008, [8] Mathaf: Arab Museum of Modern Art in 2010, [9] and the National Museum of Qatar in 2019. [10] Plans for additional museums have been announced, including the Art Mill, Lusail Museum, and Qatar Auto Museum. [11]

For the last twenty years, several members of the Al Thani family have led Qatar's interest and involvement into the field of arts and continue to shape the cultural policy of the country. [12] Qatar was revealed to be the world's biggest art buyer in 2011. [13] Figures like Sheikha Al-Mayassa bint Hamad Al Thani, [14] Sheikha Moza bint Nasser and Hassan bin Mohamed Al Thani have played instrumental roles in advancing Qatar's art scene and developing its related institutions. [15]

Architecture

Most traditional houses in the capital Doha were tightly packed and arranged around a central courtyard. A number of rooms were situated in the courtyard, most often including a majilis, bathroom and store room. The houses were made from limestone quarried from local sources. Walls surrounding the compounds were made up of compressed mud, gravel and small stones. As they were heavily susceptible to natural erosion, they were protected by gypsum plaster. Mangrove poles wrapped in jute rope provided structural support for the windows and doors. [16]

Roofs were typically flat and were supported by mangrove poles. The poles were covered with a layer of split bamboo and a palm mat locally called manghrour. The mangrove poles often extended past the exterior walls for decorative purposes. Doors were made of metal or wood. Colored glass employing geometrical designs was sometimes used in windows. [16] The local architecture shows the use of the reddish stone of Qatar, as well as little use of wood due to the scarcity of the resource in the region.

Several methods were used in traditional architecture to alleviate the harsh climate of the country. Windows were seldom used in order to reduce heat conduction. [16] The badgheer construction method allowed air to be channeled into houses for ventilation purposes. This was accomplished by several methods, including horizontal air gaps in rooms and parapets, and vertical openings in wind towers called hawaya which drew air into the courtyards. Wind towers, however, were not as common in Doha as they were in other parts of the country. [17]

Folklore

Qatari folklore is rich with narratives that reflect the cultural heritage of the Persian Gulf region, emphasizing sea-based activities. Known locally as hazzawi, folktales hold significant cultural value, with stories often passed down orally from generation to generation. One such popular myth is that of May and Ghilân. Originating from the Al Muhannadi tribe of Al Khor, the story narrates a struggle between two pearl fishers which results in the creation of the sail. [18] Another tale which carries some popularity locally is the Lord of the Sea, which revolves around a half-man half-fish monster named Bū Daryā who terrorizes sailors. [19]

Among the notable folk heroes in Qatari folklore are individuals like Qatari ibn al-Fuja'a, a celebrated war poet from the 7th century, [20] and Rahmah ibn Jabir Al Jalhami, an infamous pirate and ruler of Qatar in the 18th and 19th centuries. [21] These figures embody themes of heroism, adventure, and resilience that are woven into the fabric of Qatari culture. Recurring motifs in Qatari folklore include djinn, pearl diving, and the sea, often serving as allegories for broader cultural values such as bravery, perseverance, and the importance of community. [19]

With the advent of oil exploration and modernization, the tradition of oral storytelling gradually declined. Efforts by government ministries such as the Ministry of Culture, alongside local universities, have sought to preserve and transcribe these tales in publications. Collaborative endeavors between government agencies, educational institutions, and regional bodies like the GCC States Folklore Centre, headquartered in Doha, have played a crucial role in cataloging and promoting Qatari folklore. [22]

Literature

Qatari literature, originating in the 19th century, has evolved significantly over time, influenced by societal transformations and the nation's economic development. Initially centered around written poetry, literary expression diversified with the introduction of short stories and novels, particularly following the mid-20th-century shift spurred by oil revenues. While poetry, notably the nabati form, remained relevant, other literary genres gained prominence, reflecting changing societal dynamics, including increased female participation in the modern literature movement. [23]

The history of Qatari literature can be broadly categorized into two periods: pre-1950 and post-1950. The latter era witnessed a surge in literary output, fueled by newfound prosperity and expanding educational opportunities. [23] Sheikh Jassim bin Mohammed Al Thani's reign in the late 19th century saw early efforts to fund the printing of Islamic texts, laying the groundwork for literary investments. [24] The modern literature movement gained momentum in the 1950s, paralleling broader cultural shifts and facilitated by improved access to education and globalization. [23]

In terms of modern literature, Qatar saw the popularization of short stories and novels in the 1970s, providing platforms for both male and female writers to explore societal norms and cultural values. Qatari women were as equally involved in the literature movement as the men were, a rarity in Qatar's cultural arenas. [25] Kaltham Jaber became the first Qatari female author to publish a collection of short stories, [26] and to publish a major work when she released her anthology of short stories, dating from 1973 to the year of its publishing, 1978. [27] Novels have become vastly more popular in the 21st century, with nearly a quarter of all existing Qatari-authored novels being published post-2014. [28] Efforts to preserve and document Qatari literature have been undertaken through initiatives like the Qatar Digital Library and the establishment of literary organizations and publishing houses. [29]

Poetry

Poetry has been an integral part of the culture since pre-Islamic times. [30] Qatari ibn al-Fuja'a, a folk hero dating to the seventh-century, was renowned for writing poetry. [31] It was seen as a verbal art which fulfilled essential social functions. Having a renowned poet among its ranks was a source of pride for tribes; it is the primary way in which age-old traditions are passed down generations. Poems composed by females primarily focused on the theme of ritha, to lament. This type of poetry served as an elegy. [30]

Nabati was the primary form of oral poetry. [32] In the nineteenth-century, sheikh Jassim Al Thani composed influential Nabati poems on the political conditions in Qatar. [33] Nabati poems are broadcast on radio and televised in the country. [34]

Weaving and dyeing

Weaving and dyeing by women played a substantial role in Bedouin culture. The process of spinning sheep's and camel's wool to produce cloths was laborious. The wool was first disentangled and tied to a bobbin, which would serve as a core and keep the fibers rigid. This was followed by spinning the wool by hand on a spindle known as noul. [35] They were then placed on a vertical loom constructed from wood whereupon women would use a stick to beat the weft into place. [36]

The resulting cloths were used in rugs and carpets and tents. Tents were usually made up of naturally colored cloths, whereas rugs and carpets used dyed cloths; mainly red and yellow. [36] The dyes were fashioned from desert herbs, with simple geometrical designs being employed. The art lost popularity in the 19th century as dyes and cloths were increasingly imported from other regions in Asia. [36]

Embroidery

A simple form of embroidery practiced by Qatari women was known as kurar. It involved four women, each carrying four threads, who would braid the threads on articles of clothing - mainly thawbs or abayas. The braids, varying in color, were sewn vertically. It was similar to heavy chain stitch embroidery. [36] Gold threads, known as zari, were commonly used. They were usually imported from India. [37]

Another type of embroidery involved the designing of caps called gohfiahs. They were made from cotton and were pierced with thorns from palm-trees to allow the women to sew between the holes. This form of embroidery declined in popularity after the country began importing the caps. [37]

Khiyat al madrasa, translated as 'school embroidery', involved the stitching of furnishings by satin stitching. Prior to the stitching process, a shape was drawn onto the fabric by a skilled artist. The most common designs were birds and flowers. [38]

Music

The folk music of Qatar finds its roots in sea folk poetry, deeply influenced by the historical significance of pearl fishing. Traditional dances, such as the ardah and tanbura, are performed during festive occasions such as weddings or feasts and are accompanied by percussion instruments like al-ras and mirwas. Other commonly used types of folk instruments include stringed instruments such as the oud and rebaba, and woodwind instruments like the ney and sirttai. Notably, clapping played a major part in most folk music. [39]

Folk music traditions in Qatar are deeply ingrained in social gatherings like the majlis, where songs and dances are commonplace. Various forms of folk music, including sea songs and urban melodies, continue to thrive today as Khaliji (Gulf) music. Efforts have been made by the Ministry of Culture to preserve and document local folk music, [39] alongside efforts to form an active music scene with the establishment of music institutions like the Qatar Music Academy and the Qatar Philharmonic Orchestra.

Songs related to pearl fishing are the most popular genre of male folk music. Each song, varying in rhythm, narrates a different activity of the pearling trip, including spreading the sails, diving, and rowing the ships. Collective singing was an integral part of each pearling trip, and each ship had a designated singer, known locally as al naham. [40] A specific type of sea music, known as fijiri, originated from sea traditions and features group performances accompanied by melodic singing, rhythmic palm-tapping on water jars (known as galahs), and evocative dances that mimic the movements of the sea waves. [41] Qatari women primarily sang work songs associated with daily activities, such as wheat grinding and cooking, in groups. Public performances by women were practiced only on two annual occasions, the first being al-moradah and the second being al-ashori. [42] Classical Qatari melodies share many similarities with their Gulf conterparts, and most of the same instruments are used. [43]

Traditions

Pearling and fishing

As Qatar is an extremely arid country, [44] the traditional ways of life were confined either to nomadic pastoralism practiced by the Bedouins of the interior and to fishing and pearling, which was engaged in by the relatively settled coastal dwellers. Both fishing and pearling were done mainly using dhows, and the latter activity occasionally employed slaves. Pearling season took place from May to September and the pearls would be exported to Baghdad and elsewhere in Asia. While pearl trading was a lucrative venture for traders and dealers of pearls, the pearlers would receive few of the profits themselves. The main fishing and pearling centers of Qatar throughout its history have been Fuwayrit, Al Huwaila, and Al Bidda. [45]

Pearling is an ancient practice in the Persian Gulf, though it is not known exactly when Arabs began diving for pearls. It has been suggested that the profession dates back to the Dilmun civilization in Bahrain 5,000 years ago, which the inhabitants of Qatar came into contact with at the time. The captain of a pearling craft is called noukhadha, and is responsible for the most important tasks of a pearling trip such as managing interpersonal conflicts between the divers (al-fawwas) and the storage of pearls in the pearling vessel, which is known as al-hairat. The al-muqaddim is responsible for all ship operations while the al-sakuni is the driver of the ship. [46]

Nomadic pastoralism

Bedouin lifestyle was nomadic and consisted of frequent migration, which would come after either a water source had been used up or a grazing site was exhausted. [47] However, in Qatar, most Bedouins would only wander during the winter, as it was too hot to do so during the summer; thus, Qatar was mainly a winter grazing ground for Bedouins from the eastern region of the Arabian Peninsula. Goats and camels were the main livelihoods of Bedouins, with products from the former being used in trade and for sustenance and with camels being used as a means of transportation as well as a source of milk. Every tribe would have its own region, called dirah in Arabic, but if the resources in their dirah had become depleted, then the tribe would be forced to migrate to another tribe's dirah, potentially provoking conflicts. [45]

In the winter when tribes wandered through Qatar, [48] it was unusual for a tribe to remain at one location for a period exceeding ten days. Generally, the average daily distance traveled by Bedouins was not very long, so as to preserve energy and resources. Although the traveling speed would be greatly hastened in cases of inclement weather or far-away distances between one pastureland to another. By and large, it was easier for Bedouin tribes to thrive during the winter months, so long as the rains arrived and there was no in-fighting. Women were responsible for making clothing, taking care of children and preparing food, one popular dish being leben, which comprises fermented milk. Men, on the other hand, would frequently go hunting with hawks and dogs during the winter months. [45]

Leaders of Bedouin tribes, known as sheikhs, often gained their positions by proving themselves to be generous and competent rulers. It was expected of them to provide charity to the poorer members of the tribe should the need arise. The sheikh's wife would be expected to help solve complaints brought to her by the female members of the tribe. Bedouins often lived very modestly, lacking a consistent source of income. Nonetheless, due to the cooperation and charity between tribe members, it was rare that one would go hungry except during exceptionally long droughts. Bedouins of all classes had a reputation for being very hospitable towards guests. [45] After the discovery of oil in Qatar, most Qataris moved to urban areas and the Bedouin way of life gradually disappeared. Only a few tribes in Qatar continue this lifestyle. [49]

Migration patterns

Bedouins inhabiting the regions of north and south Qatar exhibit marked distinctions in their migratory practices, ranging from semi-sedentary lifestyles to frequent nomadism. In northern Qatar, nomads traditionally undertook only brief and sporadic movements. The Al Naim tribe, for instance, spent a considerable portion of the year, approximately six to eight months, at their summer encampments in Al Suwaihliya. Here, they erected stone houses for shelter during the hottest months, alongside their tents used as living and working spaces. Upon the onset of fall, they migrated to Al Jemailiya, where they remained for around three months before proceeding to Murwab for another three months. This cyclical pattern ensured that the Al Naim tribe remained within their tribal territory throughout the year. [50]

The nomadic lifestyle in South Qatar diverged significantly, characterized by heightened mobility and frequent migrations. Utilizing camels as their primary mode of transport, these Bedouins traversed vast sand deserts, often engaging in lengthy migrations into the interior regions. They typically migrated northward during late winter and early spring, drawn by abundant grazing opportunities for their flocks and resources for hunting and truffle-gathering. In contrast, the scorching summer months saw them establish stationary camps near wells to the south of Qatar, congregating in larger groups. Springtime, however, witnessed the formation of smaller, more transient camps. [50]

Tents

Tents (known in Arabic as khaïma) were the primary dwellings of Bedouins, and are still used present-day in the desert. In northern Qatar, the tents displayed a remarkable uniformity in appearance and structure, as well as in their furnishing and use. All sides of the tent were enclosed, ensuring complete privacy within. The interior of the tent comprised distinct sections delineated by woven walls or carpets. During the day, these divisions could be rolled up to create a unified space, swiftly reconfigured when necessary. The sections included quarters for unmarried adult men, designated guest areas, and spaces for children and young animals. Furnishings were modest, typically consisting of beddings, seating mats, and essential utensils. Notably, the central hearth served as a focal point for social gatherings and culinary activities, with water and refreshments readily available. [51]

Women predominantly managed domestic affairs within the tent, including cooking, dairy processing, and crafts such as weaving and sewing. The presence of animals within the tent, particularly during nighttime, led to inevitable accumulation of waste, a common observation in these settings. Remarkably, despite the close relationship with livestock, dogs were notably absent from these camps. [51]

In contrast, camps in southern Qatar typically comprising two to seven tents, were organized around kinship groups and facilitated seasonal migrations for grazing and resource access. The tents, while similar in appearance to those in the north, served as fully functional nomadic dwellings. Fellowship in these Bedouin groups centered around shared labor and communal activities, with a collective emphasis on safeguarding and managing resources, particularly camels. [51]

Livestock rearing