Clement Ligoure | |

|---|---|

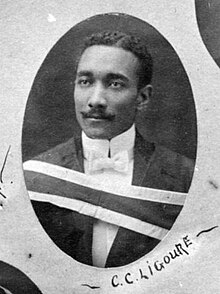

Ligoure in 1913 | |

| Born | 13 October 1887

San Fernando, Trinidad, British West Indies |

| Died | 23 May 1922 (aged 34)

Port of Spain, Colony of Trinidad and Tobago, British West Indies |

| Education | Queen's University |

| Occupation | Doctor of Medicine |

| Spouse | Vivian E. Haynes |

Clement Courtenay Ligoure (13 October 1887 – 23 May 1922) [1] was a Trinidadian doctor and newspaper publisher who was the first Black physician to practise in Nova Scotia, Canada. [2] He is also noted for treating hundreds of victims of the Halifax Explosion from his home clinic as well as being an editor and publisher of The Atlantic Advocate newspaper. [3]

Early life and education

Born in San Fernando, [4] Trinidad and Tobago, he was the son of Clement François and Amanda M. (née) Crooke. His father worked for the Supreme Court of Trinidad and Tobago. [5]

In April 1906 at age 18, Clement Ligoure immigrated to the United States. [6] That same year, he started studies at Queen's University in Ontario, Canada. [7] At the university, he earned a Bachelor of Medicine Degree in 1914 and a Doctor of Medicine degree in 1916. [5]

Career

Military and early medical work

With World War I underway, Ligoure enlisted in the Canadian military and ended up travelling to Halifax, Nova Scotia—arriving in 1916, [8] two months after getting his final degree [7]—to be a medical officer in the No. 2 Construction Battalion, [5] made up of Black recruits. However, an "error" in the application resulted in him being replaced by a white physician, "likely due to the British War Office ergo the Canadian Department of Militias and Defence refusing to see past the colour bar." [5] He still assisted by raising money [5] and spent seven months recruiting [9] for the battalion.

Despite being a licensed physician, Ligoure was not allowed to use hospitals in Halifax. [3] Still, he served as medical officer for Canadian National Railway workers. [5] His fifteen-person clinic [5] was located in his house and named the Amanda Private Hospital for his mother. [3]

Halifax Explosion

After the Halifax Explosion on 6 December 1917, Ligoure worked long hours to treat blast victims. [8] Some of the patients that filled his clinic had been unable to get medical help elsewhere. [7] In a statement to Dr. Archibald MacMechan, Ligoure conveyed that he worked day and night:

In spite of the warning of a second explosion, he worked steadily till 8 p.m. ... Seven people spent the night in his office, laid upon blankets. On December 7th, 8th and 9th, he worked steadily both night and day, doing outside work at night. [10]

At first his only support was from his housekeeper and his boarder. [5] On 10 December, Ligoure requested assistance from City Hall and received two nurses to come with him to establish an "official dressing station" for changing and applying bandages. [7] Eventually, he was leading ten nurses, six other women and four soldiers (one of whom was a physician). [7]

His work continued to 28 December, with records indicating nearly 200 patients were helped each day. [11] His patients were almost all White. [7] According to archival records, patients were not charged. [3] This work has led him to be recognized as a "local hero" [2] and "unsung hero". [12]

The Atlantic Advocate newspaper

Ligoure served as the editor and publisher of The Atlantic Advocate. [11] Publication took place in the home he had purchased in 1917 at 166 North Street. [5] It was the first newspaper in Nova Scotia owned and published by Black Canadians. [13] The newspaper ran from 1915 to 1917 and its masthead read: "Devoted to the interests of colored people." [14]

Death and legacy

During a visit with his brother Clarence in Tobago, Ligoure contracted malignant malaria. He was transported to the Colonial Hospital in Port of Spain, Trinidad, where he died on 23 May 1922. [5]

David Woods' play Extraordinary Acts, in part, dramatized Ligoure's role in the Halifax Explosion. It was scheduled to be staged in 2020, but was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. [8]

An inaugural "Dr. Clement Ligoure Award" was given in 2021 by the Doctors Nova Scotia organization to Nova Scotia's Chief Medical Officer of Health. [11] It is a non-annual prize given to a physician for handling a medical crisis in Nova Scotia. [15]

In Halifax, the former house of Ligoure (of which only a part still stands [5]) was given heritage status on 24 January 2023. The decision by Halifax's regional council followed lobbying efforts by notable Black community members. [3] The house is listed at 5812-14 North Street, [5] and was built in 1892. [3]

References

- ^ [Philip] Hartling, 1-4: PANS RG83, v3, n12, 16 Liguore, Clement C., Nova Scotia Archives, birth date in Dr. Ligoure's own handwriting on medical board application.

- ^ a b Heritage, Canadian. "Statement by Minister Hussen on Black History Month". newswire.ca. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Former home of Nova Scotia's first Black doctor granted heritage status". Global News. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Hastings, Paula (16 September 2022). Dominion over Palm and Pine: A History of Canadian Aspirations in the British Caribbean. ISBN 9780228012863. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Zemel, Joel (20 February 2023). "Dr. Clement Ligoure: A Humanitarian Approach To Medical Care". CityNews Halifax. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Zemel, Joel (14 December 2023). "New York, County Naturalization Records, 1791-1980". Retrieved 14 December 2023 – via FamilySearch.

- ^ a b c d e f Remes, Jacob A. C. (2018). "What We Talk About When We Talk About Africville". African American Review. 51 (3): 226. doi: 10.1353/afa.2018.0034. JSTOR 26795151. S2CID 165946312 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c Smith, Emma (6 December 2020). "Nova Scotia's first Black doctor treated hundreds of patients after Halifax Explosion". CBC. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Tennyson, Brian Douglas (21 November 2017). Nova Scotia at War, 1914–1919 (in Arabic). Nimbus+ORM. ISBN 978-1-77108-524-3.

- ^ MacMechan, Archibald (25 January 1918). "Personal Narrative by Dr. C. C. Ligoure to Archibald MacMechan". Nova Scotia Archives.

- ^ a b c Production, Lookout (11 February 2023). "Dr. Clement Ligoure, Nova Scotia's first Black doctor". Pacific Navy News. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Former home of Nova Scotia's first Black doctor granted heritage status". CBC. 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Carrie Best". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Deveau, Leo J. (13 October 2017). 400 Years in 365 Days: A Day by Day Calendar of Nova Scotia History. Formac Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4595-0480-6.

- ^ "Award categories". Doctors Nova Scotia. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

External links

- Personal account of the aftermath of Halifax Explosion by Clement Ligoure from Nova Scotia Archives

- Heritage Designation Application for 5812-14/ 166 North St, Halifax from Friends of the Halifax Common

- Digitized issues and overview of The Atlantic Advocate from Nova Scotia Archives

- Death Notice and Funeral of Dr. Ligoure, Port of Spain Gazette / Digital Library of the Caribbean (dLOC) from Joel Zemel article

- Historic Black Nova Scotia by Bridgial Pachai & Henry Bishop (2006, Nimbus Publishing).

- 1887 births

- 1922 deaths

- Queen's University at Kingston alumni

- Canadian newspaper editors

- Canadian newspaper publishers (people)

- 20th-century Trinidad and Tobago physicians

- 20th-century Canadian physicians

- Trinidad and Tobago emigrants to Canada

- People from San Fernando, Trinidad and Tobago

- People from Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Canadian general practitioners

- Physicians from Nova Scotia

- Black Nova Scotians

Clement Ligoure | |

|---|---|

Ligoure in 1913 | |

| Born | 13 October 1887

San Fernando, Trinidad, British West Indies |

| Died | 23 May 1922 (aged 34)

Port of Spain, Colony of Trinidad and Tobago, British West Indies |

| Education | Queen's University |

| Occupation | Doctor of Medicine |

| Spouse | Vivian E. Haynes |

Clement Courtenay Ligoure (13 October 1887 – 23 May 1922) [1] was a Trinidadian doctor and newspaper publisher who was the first Black physician to practise in Nova Scotia, Canada. [2] He is also noted for treating hundreds of victims of the Halifax Explosion from his home clinic as well as being an editor and publisher of The Atlantic Advocate newspaper. [3]

Early life and education

Born in San Fernando, [4] Trinidad and Tobago, he was the son of Clement François and Amanda M. (née) Crooke. His father worked for the Supreme Court of Trinidad and Tobago. [5]

In April 1906 at age 18, Clement Ligoure immigrated to the United States. [6] That same year, he started studies at Queen's University in Ontario, Canada. [7] At the university, he earned a Bachelor of Medicine Degree in 1914 and a Doctor of Medicine degree in 1916. [5]

Career

Military and early medical work

With World War I underway, Ligoure enlisted in the Canadian military and ended up travelling to Halifax, Nova Scotia—arriving in 1916, [8] two months after getting his final degree [7]—to be a medical officer in the No. 2 Construction Battalion, [5] made up of Black recruits. However, an "error" in the application resulted in him being replaced by a white physician, "likely due to the British War Office ergo the Canadian Department of Militias and Defence refusing to see past the colour bar." [5] He still assisted by raising money [5] and spent seven months recruiting [9] for the battalion.

Despite being a licensed physician, Ligoure was not allowed to use hospitals in Halifax. [3] Still, he served as medical officer for Canadian National Railway workers. [5] His fifteen-person clinic [5] was located in his house and named the Amanda Private Hospital for his mother. [3]

Halifax Explosion

After the Halifax Explosion on 6 December 1917, Ligoure worked long hours to treat blast victims. [8] Some of the patients that filled his clinic had been unable to get medical help elsewhere. [7] In a statement to Dr. Archibald MacMechan, Ligoure conveyed that he worked day and night:

In spite of the warning of a second explosion, he worked steadily till 8 p.m. ... Seven people spent the night in his office, laid upon blankets. On December 7th, 8th and 9th, he worked steadily both night and day, doing outside work at night. [10]

At first his only support was from his housekeeper and his boarder. [5] On 10 December, Ligoure requested assistance from City Hall and received two nurses to come with him to establish an "official dressing station" for changing and applying bandages. [7] Eventually, he was leading ten nurses, six other women and four soldiers (one of whom was a physician). [7]

His work continued to 28 December, with records indicating nearly 200 patients were helped each day. [11] His patients were almost all White. [7] According to archival records, patients were not charged. [3] This work has led him to be recognized as a "local hero" [2] and "unsung hero". [12]

The Atlantic Advocate newspaper

Ligoure served as the editor and publisher of The Atlantic Advocate. [11] Publication took place in the home he had purchased in 1917 at 166 North Street. [5] It was the first newspaper in Nova Scotia owned and published by Black Canadians. [13] The newspaper ran from 1915 to 1917 and its masthead read: "Devoted to the interests of colored people." [14]

Death and legacy

During a visit with his brother Clarence in Tobago, Ligoure contracted malignant malaria. He was transported to the Colonial Hospital in Port of Spain, Trinidad, where he died on 23 May 1922. [5]

David Woods' play Extraordinary Acts, in part, dramatized Ligoure's role in the Halifax Explosion. It was scheduled to be staged in 2020, but was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic. [8]

An inaugural "Dr. Clement Ligoure Award" was given in 2021 by the Doctors Nova Scotia organization to Nova Scotia's Chief Medical Officer of Health. [11] It is a non-annual prize given to a physician for handling a medical crisis in Nova Scotia. [15]

In Halifax, the former house of Ligoure (of which only a part still stands [5]) was given heritage status on 24 January 2023. The decision by Halifax's regional council followed lobbying efforts by notable Black community members. [3] The house is listed at 5812-14 North Street, [5] and was built in 1892. [3]

References

- ^ [Philip] Hartling, 1-4: PANS RG83, v3, n12, 16 Liguore, Clement C., Nova Scotia Archives, birth date in Dr. Ligoure's own handwriting on medical board application.

- ^ a b Heritage, Canadian. "Statement by Minister Hussen on Black History Month". newswire.ca. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f "Former home of Nova Scotia's first Black doctor granted heritage status". Global News. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Hastings, Paula (16 September 2022). Dominion over Palm and Pine: A History of Canadian Aspirations in the British Caribbean. ISBN 9780228012863. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Zemel, Joel (20 February 2023). "Dr. Clement Ligoure: A Humanitarian Approach To Medical Care". CityNews Halifax. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Zemel, Joel (14 December 2023). "New York, County Naturalization Records, 1791-1980". Retrieved 14 December 2023 – via FamilySearch.

- ^ a b c d e f Remes, Jacob A. C. (2018). "What We Talk About When We Talk About Africville". African American Review. 51 (3): 226. doi: 10.1353/afa.2018.0034. JSTOR 26795151. S2CID 165946312 – via JSTOR.

- ^ a b c Smith, Emma (6 December 2020). "Nova Scotia's first Black doctor treated hundreds of patients after Halifax Explosion". CBC. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Tennyson, Brian Douglas (21 November 2017). Nova Scotia at War, 1914–1919 (in Arabic). Nimbus+ORM. ISBN 978-1-77108-524-3.

- ^ MacMechan, Archibald (25 January 1918). "Personal Narrative by Dr. C. C. Ligoure to Archibald MacMechan". Nova Scotia Archives.

- ^ a b c Production, Lookout (11 February 2023). "Dr. Clement Ligoure, Nova Scotia's first Black doctor". Pacific Navy News. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Former home of Nova Scotia's first Black doctor granted heritage status". CBC. 24 January 2023. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ "Carrie Best". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 24 February 2023.

- ^ Deveau, Leo J. (13 October 2017). 400 Years in 365 Days: A Day by Day Calendar of Nova Scotia History. Formac Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4595-0480-6.

- ^ "Award categories". Doctors Nova Scotia. Retrieved 25 February 2023.

External links

- Personal account of the aftermath of Halifax Explosion by Clement Ligoure from Nova Scotia Archives

- Heritage Designation Application for 5812-14/ 166 North St, Halifax from Friends of the Halifax Common

- Digitized issues and overview of The Atlantic Advocate from Nova Scotia Archives

- Death Notice and Funeral of Dr. Ligoure, Port of Spain Gazette / Digital Library of the Caribbean (dLOC) from Joel Zemel article

- Historic Black Nova Scotia by Bridgial Pachai & Henry Bishop (2006, Nimbus Publishing).

- 1887 births

- 1922 deaths

- Queen's University at Kingston alumni

- Canadian newspaper editors

- Canadian newspaper publishers (people)

- 20th-century Trinidad and Tobago physicians

- 20th-century Canadian physicians

- Trinidad and Tobago emigrants to Canada

- People from San Fernando, Trinidad and Tobago

- People from Halifax, Nova Scotia

- Canadian general practitioners

- Physicians from Nova Scotia

- Black Nova Scotians