| Aspergillus fumigatus | |

|---|---|

| |

|

Scientific classification

| |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Order: | Eurotiales |

| Family: | Aspergillaceae |

| Genus: | Aspergillus |

| Species: | A. fumigatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Aspergillus fumigatus Fresenius 1863

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Neosartorya fumigata | |

Aspergillus fumigatus is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus, and is one of the most common Aspergillus species to cause disease in individuals with an immunodeficiency.

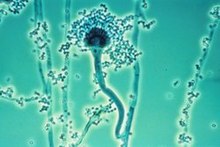

Aspergillus fumigatus, a saprotroph widespread in nature, is typically found in soil and decaying organic matter, such as compost heaps, where it plays an essential role in carbon and nitrogen recycling. [1] Colonies of the fungus produce from conidiophores; thousands of minute grey-green conidia (2–3 μm) which readily become airborne. For many years, A. fumigatus was thought to only reproduce asexually, as neither mating nor meiosis had ever been observed. In 2008, A. fumigatus was shown to possess a fully functional sexual reproductive cycle, 145 years after its original description by Fresenius. [2] Although A. fumigatus occurs in areas with widely different climates and environments, it displays low genetic variation and a lack of population genetic differentiation on a global scale. [3] Thus, the capability for sex is maintained, though little genetic variation is produced.

The fungus is capable of growth at 37 °C or 99 °F ( normal human body temperature), and can grow at temperatures up to 50 °C or 122 °F, with conidia surviving at 70 °C or 158 °F—conditions it regularly encounters in self-heating compost heaps. Its spores are ubiquitous in the atmosphere, and everybody inhales an estimated several hundred spores each day; typically, these are quickly eliminated by the immune system in healthy individuals. In immunocompromised individuals, such as organ transplant recipients and people with AIDS or leukemia, the fungus is more likely to become pathogenic, over-running the host's weakened defenses and causing a range of diseases generally termed aspergillosis. Due to the recent increase in the use of immunosuppressants to treat human illnesses, it is estimated that A. fumigatus may be responsible for over 600,000 deaths annually with a mortality rate between 25 and 90%. [4] Several virulence factors have been postulated to explain this opportunistic behaviour. [5]

When the fermentation broth of A. fumigatus was screened, a number of indolic alkaloids with antimitotic properties were discovered. [6] The compounds of interest have been of a class known as tryprostatins, with spirotryprostatin B being of special interest as an anticancer drug.

Aspergillus fumigatus grown on certain building materials can produce genotoxic and cytotoxic mycotoxins, such as gliotoxin. [7]

Genome

Aspergillus fumigatus has a stable haploid genome of 29.4 million base pairs. The genome sequences of three Aspergillus species—Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus nidulans, and Aspergillus oryzae—were published in Nature in December 2005. [8] [9] [10]

Pathogenesis

Aspergillus fumigatus is the most frequent cause of invasive fungal infection in immunosuppressed individuals, which include patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune or neoplastic disease, organ transplant recipients, and AIDS patients. [11] A. fumigatus primarily causes invasive infection in the lung and represents a major cause of morbidity and mortality in these individuals. [12] Additionally, A. fumigatus can cause chronic pulmonary infections, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, or allergic disease in immunocompetent hosts. [13]

Innate immune response

Inhalational exposure to airborne conidia is continuous due to their ubiquitous distribution in the environment. However, in healthy individuals, the innate immune system is an efficacious barrier to A. fumigatus infection. [13] A large portion of inhaled conidia are cleared by the mucociliary action of the respiratory epithelium. [13] Due to the small size of conidia, many of them deposit in alveoli, where they interact with epithelial and innate effector cells. [11] [13] Alveolar macrophages phagocytize and destroy conidia within their phagosomes. [11] [13] Epithelial cells, specifically type II pneumocytes, also internalize conidia which traffic to the lysosome where ingested conidia are destroyed. [11] [13] [14] First line immune cells also serve to recruit neutrophils and other inflammatory cells through release of cytokines and chemokines induced by ligation of specific fungal motifs to pathogen recognition receptors. [13] Neutrophils are essential for aspergillosis resistance, as demonstrated in neutropenic individuals, and are capable of sequestering both conidia and hyphae through distinct, non-phagocytic mechanisms. [11] [12] [13] Hyphae are too large for cell-mediated internalization, and thus neutrophil-mediated NADPH-oxidase induced damage represents the dominant host defense against hyphae. [11] [13] In addition to these cell-mediated mechanisms of elimination, antimicrobial peptides secreted by the airway epithelium contribute to host defense. [11] The fungus and its polysaccharides have ability to regulate the functions of dendritic cells by Wnt-β-Catenin signaling pathway to induce PD-L1 and to promote regulatory T cell responses [15] [16]

Invasion

Immunosuppressed individuals are susceptible to invasive A. fumigatus infection, which most commonly manifests as invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Inhaled conidia that evade host immune destruction are the progenitors of invasive disease. These conidia emerge from dormancy and make a morphological switch to hyphae by germinating in the warm, moist, nutrient-rich environment of the pulmonary alveoli. [11] Germination occurs both extracellularly or in type II pneumocyte endosomes containing conidia. [11] [14] Following germination, filamentous hyphal growth results in epithelial penetration and subsequent penetration of the vascular endothelium. [11] [14] The process of angioinvasion causes endothelial damage and induces a proinflammatory response, tissue factor expression and activation of the coagulation cascade. [11] This results in intravascular thrombosis and localized tissue infarction, however, dissemination of hyphal fragments is usually limited. [11] [14] Dissemination through the blood stream only occurs in severely immunocompromised individuals. [14]

Hypoxia response

As is common with tumor cells and other pathogens, the invasive hyphae of A. fumigatus encounters hypoxic (low oxygen levels, ≤ 1%) micro-environments at the site of infection in the host organism. [17] [18] [19] Current research suggests that upon infection, necrosis and inflammation cause tissue damage which decreases available oxygen concentrations due to a local reduction in perfusion, the passaging of fluids to organs. In A. fumigatus specifically, secondary metabolites have been found to inhibit the development of new blood vessels leading to tissue damage, the inhibition of tissue repair, and ultimately localized hypoxic micro-environments. [18] The exact implications of hypoxia on fungal pathogenesis is currently unknown, however these low oxygen environments have long been associated with negative clinical outcomes. Due to the significant correlations identified between hypoxia, fungal infections, and negative clinical outcomes, the mechanisms by which A. fumigatus adapts in hypoxia is a growing area of focus for novel drug targets.

Two highly characterized sterol-regulatory element binding proteins, SrbA and SrbB, along with their processing pathways, have been shown to impact the fitness of A. fumigatus in hypoxic conditions. The transcription factor SrbA is the master regulator in the fungal response to hypoxia in vivo and is essential in many biological processes including iron homeostasis, antifungal azole drug resistance, and virulence. [20] Consequently, the loss of SrbA results in an inability for A. fumigatus to grow in low iron conditions, a higher sensitivity to anti-fungal azole drugs, and a complete loss of virulence in IPA (invasive pulmonary aspergillosis) mouse models. [21] SrbA knockout mutants do not show any signs of in vitro growth in low oxygen, which is thought to be associated with the attenuated virulence. SrbA functionality in hypoxia is dependent upon an upstream cleavage process carried out by the proteins RbdB, SppA, and Dsc A-E. [22] [23] [24] SrbA is cleaved from an endoplasmic reticulum residing 1015 amino acid precursor protein to a 381 amino acid functional form. The loss of any of the above SrbA processing proteins results in a dysfunctional copy of SrbA and a subsequent loss of in vitro growth in hypoxia as well as attenuated virulence. Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies with the SrbA protein led to the identification of a second hypoxia regulator, SrbB. [21] Although little is known about the processing of SrbB, this transcription factor has also shown to be a key player in virulence and the fungal hypoxia response. [21] Similar to SrbA, a SrbB knockout mutant resulted in a loss of virulence, however, there was no heightened sensitivity towards antifungal drugs nor a complete loss of growth under hypoxic conditions (50% reduction in SrbB rather than 100% reduction in SrbA). [21] [20] In summary, both SrbA and SrbB have shown to be critical in the adaptation of A. fumigatus in the mammalian host.

Nutrient acquisition

Aspergillus fumigatus must acquire nutrients from its external environment to survive and flourish within its host. Many of the genes involved in such processes have been shown to impact virulence through experiments involving genetic mutation. Examples of nutrient uptake include that of metals, nitrogen, and macromolecules such as peptides. [12] [25]

Iron acquisition

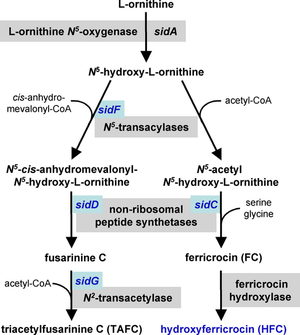

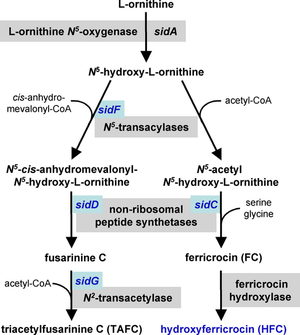

Iron is a necessary cofactor for many enzymes, and can act as a catalyst in the electron transport system. A. fumigatus has two mechanisms for the uptake of iron, reductive iron acquisition and siderophore-mediated. [27] [28] Reductive iron acquisition includes conversion of iron from the ferric (Fe+3) to the ferrous (Fe+2) state and subsequent uptake via FtrA, an iron permease. Targeted mutation of the ftrA gene did not induce a decrease in virulence in the murine model of A. fumigatus invasion. In contrast, targeted mutation of sidA, the first gene in the siderophore biosynthesis pathway, proved siderophore-mediated iron uptake to be essential for virulence. [28] [29] Mutation of the downstream siderophore biosynthesis genes sidC, sidD, sidF and sidG resulted in strains of A. fumigatus with similar decreases in virulence. [26] These mechanisms of iron uptake appear to work in parallel and both are upregulated in response to iron starvation. [28]

Nitrogen assimilation

Aspergillus fumigatus can survive on a variety of different nitrogen sources, and the assimilation of nitrogen is of clinical importance, as it has been shown to affect virulence. [25] [30] Proteins involved in nitrogen assimilation are transcriptionally regulated by the AfareA gene in A. fumigatus. Targeted mutation of the afareA gene showed a decrease in onset of mortality in a mouse model of invasion. [30] The Ras regulated protein RhbA has also been implicated in nitrogen assimilation. RhbA was found to be transcriptionally upregulated following contact of A. fumigatus with human endothelial cells, and strains with targeted mutation of the rhbA gene showed decreased growth on poor nitrogen sources and reduced virulence in vivo. [31]

Proteinases

The human lung contains large quantities of collagen and elastin, proteins that allow for tissue flexibility. [32] Aspergillus fumigatus produces and secretes elastases, proteases that cleave elastin in order to break down these macromolecular polymers for uptake. A significant correlation between the amount of elastase production and tissue invasion was first discovered in 1984. [33] Clinical isolates have also been found to have greater elastase activity than environmental strains of A. fumigatus. [34] A number of elastases have been characterized, including those from the serine protease, aspartic protease, and metalloprotease families. [35] [36] [37] [38] Yet, the large redundancy of these elastases has hindered the identification of specific effects on virulence. [12] [25]

Unfolded protein response

A number of studies found that the unfolded protein response contributes to virulence of A. fumigatus. [39]

Secondary metabolism

Secondary metabolites in fungal development

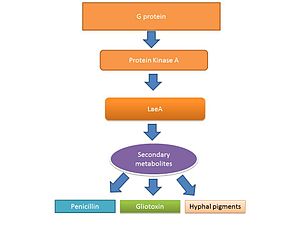

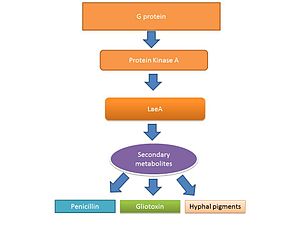

The lifecycle of filamentous fungi including Aspergillus spp. consists of two phases: a hyphal growth phase and a reproductive ( sporulation) phase. The switch between growth and reproductive phases of these fungi is regulated in part by the level of secondary metabolite production. [41] [42] The secondary metabolites are believed to be produced to activate sporulation and pigments required for sporulation structures. [43] G protein signaling regulates secondary metabolite production. [44] Genome sequencing has revealed 40 potential genes involved in secondary metabolite production including mycotoxins, which are produced at the time of sporulation. [9] [45]

Gliotoxin

Gliotoxin is a mycotoxin capable of altering host defenses through immunosuppression. Neutrophils are the principal targets of gliotoxin. [46] [47] Gliotoxin interrupts the function of leukocytes by inhibiting migration and superoxide production and causes apoptosis in macrophages. [48] Gliotoxin disrupts the proinflammatory response through inhibition of NF-κB. [49]

Transcriptional regulation of gliotoxin

LaeA and GliZ are transcription factors known to regulate the production of gliotoxin. LaeA is a universal regulator of secondary metabolite production in Aspergillus spp. [40] LaeA influences the expression of 9.5% of the A. fumigatus genome, including many secondary metabolite biosynthesis genes such as nonribosomal peptide synthetases. [50] The production of numerous secondary metabolites, including gliotoxin, were impaired in an LaeA mutant (ΔlaeA) strain. [50] The ΔlaeA mutant showed increased susceptibility to macrophage phagocytosis and decreased ability to kill neutrophils ex vivo. [47] LaeA regulated toxins, besides gliotoxin, likely have a role in virulence since loss of gliotoxin production alone did not recapitulate the hypo-virulent ∆laeA pathotype. [50]

Current treatments to combat A. fumigatus infections

Current noninvasive treatments used to combat fungal infections consist of a class of drugs known as azoles. Azole drugs such as voriconazole, itraconazole, and imidazole kill fungi by inhibiting the production of ergosterol—a critical element of fungal cell membranes. Mechanistically, these drugs act by inhibiting the fungal cytochrome p450 enzyme known as 14α-demethylase. [51] However, A. fumigatus resistance to azoles is increasing, potentially due to the use of low levels of azoles in agriculture. [52] [53] The main mode of resistance is through mutations in the cyp51a gene. [54] [55] However, other modes of resistance have been observed accounting for almost 40% of resistance in clinical isolates. [56] [57] [58] Along with azoles, other anti-fungal drug classes do exist such as polyenes and echinocandins.[ citation needed]

Gallery

-

Conidia phialoconidia of A. fumigatus

-

Colony in Petri dish

-

A. fumigatus isolated from woodland soil

-

Slide of an infected turkey brain

See also

References

- ^ Fang W, Latgé JP (August 2018). "Microbe Profile: Aspergillus fumigatus: a saprotrophic and opportunistic fungal pathogen". Microbiology. 164 (8): 1009–1011. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000651. PMC 6152418. PMID 30066670.

- ^ O'Gorman CM, Fuller H, Dyer PS (January 2009). "Discovery of a sexual cycle in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus". Nature. 457 (7228): 471–4. Bibcode: 2009Natur.457..471O. doi: 10.1038/nature07528. PMID 19043401. S2CID 4371721.

- ^ Rydholm C, Szakacs G, Lutzoni F (April 2006). "Low genetic variation and no detectable population structure in aspergillus fumigatus compared to closely related Neosartorya species". Eukaryotic Cell. 5 (4): 650–7. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.4.650-657.2006. PMC 1459663. PMID 16607012.

- ^ Dhingra S, Cramer RA (2017). "Regulation of Sterol Biosynthesis in the Human Fungal Pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus: Opportunities for Therapeutic Development". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8: 92. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00092. PMC 5285346. PMID 28203225.

- ^ Abad A, Fernández-Molina JV, Bikandi J, Ramírez A, Margareto J, Sendino J, et al. (December 2010). "What makes Aspergillus fumigatus a successful pathogen? Genes and molecules involved in invasive aspergillosis" (PDF). Revista Iberoamericana de Micologia. 27 (4): 155–82. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2010.10.003. PMID 20974273.

- ^ Cui CB, Kakeya H, Osada H (August 1996). "Spirotryprostatin B, a novel mammalian cell cycle inhibitor produced by Aspergillus fumigatus". The Journal of Antibiotics. 49 (8): 832–5. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.832. PMID 8823522.

- ^ Nieminen SM, Kärki R, Auriola S, Toivola M, Laatsch H, Laatikainen R, et al. (October 2002). "Isolation and identification of Aspergillus fumigatus mycotoxins on growth medium and some building materials". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 68 (10): 4871–5. Bibcode: 2002ApEnM..68.4871N. doi: 10.1128/aem.68.10.4871-4875.2002. PMC 126391. PMID 12324333.

- ^ Galagan JE, Calvo SE, Cuomo C, Ma LJ, Wortman JR, Batzoglou S, et al. (December 2005). "Sequencing of Aspergillus nidulans and comparative analysis with A. fumigatus and A. oryzae". Nature. 438 (7071): 1105–15. Bibcode: 2005Natur.438.1105G. doi: 10.1038/nature04341. PMID 16372000.

- ^ a b Nierman WC, Pain A, Anderson MJ, Wortman JR, Kim HS, Arroyo J, et al. (December 2005). "Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus". Nature. 438 (7071): 1151–6. Bibcode: 2005Natur.438.1151N. doi: 10.1038/nature04332. hdl: 10261/71531. PMID 16372009.

- ^ Machida M, Asai K, Sano M, Tanaka T, Kumagai T, Terai G, et al. (December 2005). "Genome sequencing and analysis of Aspergillus oryzae". Nature. 438 (7071): 1157–61. Bibcode: 2005Natur.438.1157M. doi: 10.1038/nature04300. PMID 16372010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ben-Ami R, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP (August 2010). "Enemy of the (immunosuppressed) state: an update on the pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus infection". British Journal of Haematology. 150 (4): 406–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08283.x. PMID 20618330. S2CID 28216163.

- ^ a b c d Hohl TM, Feldmesser M (November 2007). "Aspergillus fumigatus: principles of pathogenesis and host defense". Eukaryotic Cell. 6 (11): 1953–63. doi: 10.1128/EC.00274-07. PMC 2168400. PMID 17890370.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Segal BH (April 2009). "Aspergillosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (18): 1870–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808853. PMID 19403905.

- ^ a b c d e f Filler SG, Sheppard DC (December 2006). "Fungal invasion of normally non-phagocytic host cells". PLOS Pathogens. 2 (12): e129. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020129. PMC 1757199. PMID 17196036.

- ^ Karnam A, Bonam SR, Rambabu N, Wong SS, Aimanianda V, Bayry J (November 16, 2021). "Wnt-β-Catenin Signaling in Human Dendritic Cells Mediates Regulatory T-Cell Responses to Fungi via the PD-L1 Pathway". mBio. 12 (6): e0282421. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02824-21. PMC 8593687. PMID 34781737.

- ^ Stephen-Victor E, Karnam A, Fontaine T, Beauvais A, Das M, Hegde P, Prakhar P, Holla S, Balaji KN, Kaveri SV, Latgé JP, Aimanianda V, Bayry J (December 5, 2017). "Aspergillus fumigatus Cell Wall α-(1,3)-Glucan Stimulates Regulatory T-Cell Polarization by Inducing PD-L1 Expression on Human Dendritic Cells". J Infect Dis. 216 (10): 1281–1294. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix469. PMID 28968869.

- ^ Grahl N, Cramer RA (February 2010). "Regulation of hypoxia adaptation: an overlooked virulence attribute of pathogenic fungi?". Medical Mycology. 48 (1): 1–15. doi: 10.3109/13693780902947342. PMC 2898717. PMID 19462332.

- ^ a b Grahl N, Shepardson KM, Chung D, Cramer RA (May 2012). "Hypoxia and fungal pathogenesis: to air or not to air?". Eukaryotic Cell. 11 (5): 560–70. doi: 10.1128/EC.00031-12. PMC 3346435. PMID 22447924.

- ^ Wezensky SJ, Cramer RA (April 2011). "Implications of hypoxic microenvironments during invasive aspergillosis". Medical Mycology. 49 (Suppl 1): S120–4. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.495139. PMC 2951492. PMID 20560863.

- ^ a b Willger SD, Puttikamonkul S, Kim KH, Burritt JB, Grahl N, Metzler LJ, Barbuch R, Bard M, Lawrence CB, Cramer RA (November 2008). "A sterol-regulatory element binding protein is required for cell polarity, hypoxia adaptation, azole drug resistance, and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus". PLOS Pathogens. 4 (11): e1000200. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000200. PMC 2572145. PMID 18989462.

- ^ a b c d Chung D, Barker BM, Carey CC, Merriman B, Werner ER, Lechner BE, Dhingra S, Cheng C, Xu W, Blosser SJ, Morohashi K, Mazurie A, Mitchell TK, Haas H, Mitchell AP, Cramer RA (November 2014). "ChIP-seq and in vivo transcriptome analyses of the Aspergillus fumigatus SREBP SrbA reveals a new regulator of the fungal hypoxia response and virulence". PLOS Pathogens. 10 (11): e1004487. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004487. PMC 4223079. PMID 25375670.

- ^ Dhingra S, Kowalski CH, Thammahong A, Beattie SR, Bultman KM, Cramer RA (2016). "RbdB, a Rhomboid Protease Critical for SREBP Activation and Virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus". mSphere. 1 (2). doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00035-16. PMC 4863583. PMID 27303716.

- ^ Bat-Ochir C, Kwak JY, Koh SK, Jeon MH, Chung D, Lee YW, Chae SK (May 2016). "The signal peptide peptidase SppA is involved in sterol regulatory element-binding protein cleavage and hypoxia adaptation in Aspergillus nidulans". Molecular Microbiology. 100 (4): 635–55. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13341. PMID 26822492.

- ^ Willger SD, Cornish EJ, Chung D, Fleming BA, Lehmann MM, Puttikamonkul S, Cramer RA (December 2012). "Dsc orthologs are required for hypoxia adaptation, triazole drug responses, and fungal virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus". Eukaryotic Cell. 11 (12): 1557–67. doi: 10.1128/EC.00252-12. PMC 3536281. PMID 23104569.

- ^ a b c Dagenais TR, Keller NP (July 2009). "Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in Invasive Aspergillosis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 22 (3): 447–65. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00055-08. PMC 2708386. PMID 19597008.

- ^ a b Schrettl M, Bignell E, Kragl C, Sabiha Y, Loss O, Eisendle M, et al. (September 2007). "Distinct roles for intra- and extracellular siderophores during Aspergillus fumigatus infection". PLOS Pathogens. 3 (9): 1195–207. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030128. PMC 1971116. PMID 17845073.

- ^ Haas H (September 2003). "Molecular genetics of fungal siderophore biosynthesis and uptake: the role of siderophores in iron uptake and storage". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 62 (4): 316–30. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1335-2. PMID 12759789. S2CID 10989925.

- ^ a b c Schrettl M, Bignell E, Kragl C, Joechl C, Rogers T, Arst HN, et al. (November 2004). "Siderophore biosynthesis but not reductive iron assimilation is essential for Aspergillus fumigatus virulence". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 200 (9): 1213–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041242. PMC 2211866. PMID 15504822.

- ^ Hissen AH, Wan AN, Warwas ML, Pinto LJ, Moore MM (September 2005). "The Aspergillus fumigatus siderophore biosynthetic gene sidA, encoding L-ornithine N5-oxygenase, is required for virulence". Infection and Immunity. 73 (9): 5493–503. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5493-5503.2005. PMC 1231119. PMID 16113265.

- ^ a b Hensel M, Arst HN, Aufauvre-Brown A, Holden DW (June 1998). "The role of the Aspergillus fumigatus areA gene in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis". Molecular & General Genetics. 258 (5): 553–7. doi: 10.1007/s004380050767. PMID 9669338. S2CID 27753283.

- ^ Panepinto JC, Oliver BG, Amlung TW, Askew DS, Rhodes JC (August 2002). "Expression of the Aspergillus fumigatus rheb homologue, rhbA, is induced by nitrogen starvation". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 36 (3): 207–14. doi: 10.1016/S1087-1845(02)00022-1. PMID 12135576.

- ^ Rosenbloom J (December 1984). "Elastin: relation of protein and gene structure to disease". Laboratory Investigation; A Journal of Technical Methods and Pathology. 51 (6): 605–23. PMID 6150137.

- ^ Kothary MH, Chase T, Macmillan JD (January 1984). "Correlation of elastase production by some strains of Aspergillus fumigatus with ability to cause pulmonary invasive aspergillosis in mice". Infection and Immunity. 43 (1): 320–5. doi: 10.1128/IAI.43.1.320-325.1984. PMC 263429. PMID 6360904.

- ^ Blanco JL, Hontecillas R, Bouza E, Blanco I, Pelaez T, Muñoz P, et al. (May 2002). "Correlation between the elastase activity index and invasiveness of clinical isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40 (5): 1811–3. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.5.1811-1813.2002. PMC 130931. PMID 11980964.

- ^ Reichard U, Büttner S, Eiffert H, Staib F, Rüchel R (December 1990). "Purification and characterisation of an extracellular serine proteinase from Aspergillus fumigatus and its detection in tissue". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 33 (4): 243–51. doi: 10.1099/00222615-33-4-243. PMID 2258912.

- ^ Markaryan A, Morozova I, Yu H, Kolattukudy PE (June 1994). "Purification and characterization of an elastinolytic metalloprotease from Aspergillus fumigatus and immunoelectron microscopic evidence of secretion of this enzyme by the fungus invading the murine lung". Infection and Immunity. 62 (6): 2149–57. doi: 10.1128/IAI.62.6.2149-2157.1994. PMC 186491. PMID 8188335.

- ^ Lee JD, Kolattukudy PE (October 1995). "Molecular cloning of the cDNA and gene for an elastinolytic aspartic proteinase from Aspergillus fumigatus and evidence of its secretion by the fungus during invasion of the host lung". Infection and Immunity. 63 (10): 3796–803. doi: 10.1128/IAI.63.10.3796-3803.1995. PMC 173533. PMID 7558282.

- ^ Iadarola P, Lungarella G, Martorana PA, Viglio S, Guglielminetti M, Korzus E, et al. (1998). "Lung injury and degradation of extracellular matrix components by Aspergillus fumigatus serine proteinase". Experimental Lung Research. 24 (3): 233–51. doi: 10.3109/01902149809041532. PMID 9635248.

- ^ Feng X, Krishnan K, Richie DL, Aimanianda V, Hartl L, Grahl N, et al. (October 2011). "HacA-independent functions of the ER stress sensor IreA synergize with the canonical UPR to influence virulence traits in Aspergillus fumigatus". PLOS Pathogens. 7 (10): e1002330. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002330. PMC 3197630. PMID 22028661.

- ^ a b Bok JW, Keller NP (April 2004). "LaeA, a regulator of secondary metabolism in Aspergillus spp". Eukaryotic Cell. 3 (2): 527–35. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.2.527-535.2004. PMC 387652. PMID 15075281.

- ^ Calvo AM, Wilson RA, Bok JW, Keller NP (September 2002). "Relationship between secondary metabolism and fungal development". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 66 (3): 447–59, table of contents. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.447-459.2002. PMC 120793. PMID 12208999.

- ^ Tao L, Yu JH (February 2011). "AbaA and WetA govern distinct stages of Aspergillus fumigatus development". Microbiology. 157 (Pt 2): 313–26. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.044271-0. PMID 20966095.

- ^ Adams TH, Yu JH (December 1998). "Coordinate control of secondary metabolite production and asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 1 (6): 674–7. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(98)80114-8. PMID 10066549.

- ^ Brodhagen M, Keller NP (July 2006). "Signalling pathways connecting mycotoxin production and sporulation". Molecular Plant Pathology. 7 (4): 285–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00338.x. PMID 20507448.

- ^ Trail F, Mahanti N, Linz J (April 1995). "Molecular biology of aflatoxin biosynthesis". Microbiology. 141 (4): 755–65. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-4-755. PMID 7773383.

- ^ Spikes S, Xu R, Nguyen CK, Chamilos G, Kontoyiannis DP, Jacobson RH, et al. (February 2008). "Gliotoxin production in Aspergillus fumigatus contributes to host-specific differences in virulence". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 197 (3): 479–86. doi: 10.1086/525044. PMID 18199036.

- ^ a b Bok JW, Chung D, Balajee SA, Marr KA, Andes D, Nielsen KF, et al. (December 2006). "GliZ, a transcriptional regulator of gliotoxin biosynthesis, contributes to Aspergillus fumigatus virulence". Infection and Immunity. 74 (12): 6761–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00780-06. PMC 1698057. PMID 17030582.

- ^ Kamei K, Watanabe A (May 2005). "Aspergillus mycotoxins and their effect on the host". Medical Mycology. 43 (Suppl 1): S95-9. doi: 10.1080/13693780500051547. PMID 16110799.

- ^ Gardiner DM, Waring P, Howlett BJ (April 2005). "The epipolythiodioxopiperazine (ETP) class of fungal toxins: distribution, mode of action, functions and biosynthesis". Microbiology. 151 (Pt 4): 1021–1032. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27847-0. PMID 15817772.

- ^ a b c Perrin RM, Fedorova ND, Bok JW, Cramer RA, Wortman JR, Kim HS, et al. (April 2007). "Transcriptional regulation of chemical diversity in Aspergillus fumigatus by LaeA". PLOS Pathogens. 3 (4): e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030050. PMC 1851976. PMID 17432932.

- ^ Panackal AA, Bennett JE, Williamson PR (September 2014). "Treatment options in Invasive Aspergillosis". Current Treatment Options in Infectious Diseases. 6 (3): 309–325. doi: 10.1007/s40506-014-0016-2. PMC 4200583. PMID 25328449.

- ^ Berger S, El Chazli Y, Babu AF, Coste AT (2017-06-07). "Aspergillus fumigatus: A Consequence of Antifungal Use in Agriculture?". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8: 1024. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01024. PMC 5461301. PMID 28638374.

- ^ Bueid A, Howard SJ, Moore CB, Richardson MD, Harrison E, Bowyer P, Denning DW (October 2010). "Azole antifungal resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: 2008 and 2009". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 65 (10): 2116–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq279. PMID 20729241.

- ^ Nash A, Rhodes J (April 2018). "Simulations of CYP51A from Aspergillus fumigatus in a model bilayer provide insights into triazole drug resistance". Medical Mycology. 56 (3): 361–373. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx056. PMC 5895076. PMID 28992260.

- ^ Snelders E, Karawajczyk A, Schaftenaar G, Verweij PE, Melchers WJ (June 2010). "Azole resistance profile of amino acid changes in Aspergillus fumigatus CYP51A based on protein homology modeling". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (6): 2425–30. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01599-09. PMC 2876375. PMID 20385860.

- ^ Rybak JM, Ge W, Wiederhold NP, Parker JE, Kelly SL, Rogers PD, Fortwendel JR (April 2019). Alspaugh JA (ed.). "hmg1, Challenging the Paradigm of Clinical Triazole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus". mBio. 10 (2): e00437–19, /mbio/10/2/mBio.00437–19.atom. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00437-19. PMC 6445940. PMID 30940706.

- ^ Camps SM, Dutilh BE, Arendrup MC, Rijs AJ, Snelders E, Huynen MA, et al. (2012-11-30). "Discovery of a HapE mutation that causes azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus through whole genome sequencing and sexual crossing". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e50034. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...750034C. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050034. PMC 3511431. PMID 23226235.

- ^ Furukawa T, van Rhijn N, Fraczek M, Gsaller F, Davies E, Carr P, et al. (January 2020). "The negative cofactor 2 complex is a key regulator of drug resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 427. Bibcode: 2020NatCo..11..427F. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14191-1. PMC 7194077. PMID 31969561.

External links

- Emergence of Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and Spread of a Single Resistance Mechanism. at SciVee

- The Aspergillus Trust A registered UK charity engaged in support of people with aspergillus disease worldwide and research into cures

- The Fungal Research Trust

- Aspergillus info from DoctorFungus.org

| Aspergillus fumigatus | |

|---|---|

| |

|

Scientific classification

| |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Fungi |

| Division: | Ascomycota |

| Class: | Eurotiomycetes |

| Order: | Eurotiales |

| Family: | Aspergillaceae |

| Genus: | Aspergillus |

| Species: | A. fumigatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Aspergillus fumigatus Fresenius 1863

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Neosartorya fumigata | |

Aspergillus fumigatus is a species of fungus in the genus Aspergillus, and is one of the most common Aspergillus species to cause disease in individuals with an immunodeficiency.

Aspergillus fumigatus, a saprotroph widespread in nature, is typically found in soil and decaying organic matter, such as compost heaps, where it plays an essential role in carbon and nitrogen recycling. [1] Colonies of the fungus produce from conidiophores; thousands of minute grey-green conidia (2–3 μm) which readily become airborne. For many years, A. fumigatus was thought to only reproduce asexually, as neither mating nor meiosis had ever been observed. In 2008, A. fumigatus was shown to possess a fully functional sexual reproductive cycle, 145 years after its original description by Fresenius. [2] Although A. fumigatus occurs in areas with widely different climates and environments, it displays low genetic variation and a lack of population genetic differentiation on a global scale. [3] Thus, the capability for sex is maintained, though little genetic variation is produced.

The fungus is capable of growth at 37 °C or 99 °F ( normal human body temperature), and can grow at temperatures up to 50 °C or 122 °F, with conidia surviving at 70 °C or 158 °F—conditions it regularly encounters in self-heating compost heaps. Its spores are ubiquitous in the atmosphere, and everybody inhales an estimated several hundred spores each day; typically, these are quickly eliminated by the immune system in healthy individuals. In immunocompromised individuals, such as organ transplant recipients and people with AIDS or leukemia, the fungus is more likely to become pathogenic, over-running the host's weakened defenses and causing a range of diseases generally termed aspergillosis. Due to the recent increase in the use of immunosuppressants to treat human illnesses, it is estimated that A. fumigatus may be responsible for over 600,000 deaths annually with a mortality rate between 25 and 90%. [4] Several virulence factors have been postulated to explain this opportunistic behaviour. [5]

When the fermentation broth of A. fumigatus was screened, a number of indolic alkaloids with antimitotic properties were discovered. [6] The compounds of interest have been of a class known as tryprostatins, with spirotryprostatin B being of special interest as an anticancer drug.

Aspergillus fumigatus grown on certain building materials can produce genotoxic and cytotoxic mycotoxins, such as gliotoxin. [7]

Genome

Aspergillus fumigatus has a stable haploid genome of 29.4 million base pairs. The genome sequences of three Aspergillus species—Aspergillus fumigatus, Aspergillus nidulans, and Aspergillus oryzae—were published in Nature in December 2005. [8] [9] [10]

Pathogenesis

Aspergillus fumigatus is the most frequent cause of invasive fungal infection in immunosuppressed individuals, which include patients receiving immunosuppressive therapy for autoimmune or neoplastic disease, organ transplant recipients, and AIDS patients. [11] A. fumigatus primarily causes invasive infection in the lung and represents a major cause of morbidity and mortality in these individuals. [12] Additionally, A. fumigatus can cause chronic pulmonary infections, allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis, or allergic disease in immunocompetent hosts. [13]

Innate immune response

Inhalational exposure to airborne conidia is continuous due to their ubiquitous distribution in the environment. However, in healthy individuals, the innate immune system is an efficacious barrier to A. fumigatus infection. [13] A large portion of inhaled conidia are cleared by the mucociliary action of the respiratory epithelium. [13] Due to the small size of conidia, many of them deposit in alveoli, where they interact with epithelial and innate effector cells. [11] [13] Alveolar macrophages phagocytize and destroy conidia within their phagosomes. [11] [13] Epithelial cells, specifically type II pneumocytes, also internalize conidia which traffic to the lysosome where ingested conidia are destroyed. [11] [13] [14] First line immune cells also serve to recruit neutrophils and other inflammatory cells through release of cytokines and chemokines induced by ligation of specific fungal motifs to pathogen recognition receptors. [13] Neutrophils are essential for aspergillosis resistance, as demonstrated in neutropenic individuals, and are capable of sequestering both conidia and hyphae through distinct, non-phagocytic mechanisms. [11] [12] [13] Hyphae are too large for cell-mediated internalization, and thus neutrophil-mediated NADPH-oxidase induced damage represents the dominant host defense against hyphae. [11] [13] In addition to these cell-mediated mechanisms of elimination, antimicrobial peptides secreted by the airway epithelium contribute to host defense. [11] The fungus and its polysaccharides have ability to regulate the functions of dendritic cells by Wnt-β-Catenin signaling pathway to induce PD-L1 and to promote regulatory T cell responses [15] [16]

Invasion

Immunosuppressed individuals are susceptible to invasive A. fumigatus infection, which most commonly manifests as invasive pulmonary aspergillosis. Inhaled conidia that evade host immune destruction are the progenitors of invasive disease. These conidia emerge from dormancy and make a morphological switch to hyphae by germinating in the warm, moist, nutrient-rich environment of the pulmonary alveoli. [11] Germination occurs both extracellularly or in type II pneumocyte endosomes containing conidia. [11] [14] Following germination, filamentous hyphal growth results in epithelial penetration and subsequent penetration of the vascular endothelium. [11] [14] The process of angioinvasion causes endothelial damage and induces a proinflammatory response, tissue factor expression and activation of the coagulation cascade. [11] This results in intravascular thrombosis and localized tissue infarction, however, dissemination of hyphal fragments is usually limited. [11] [14] Dissemination through the blood stream only occurs in severely immunocompromised individuals. [14]

Hypoxia response

As is common with tumor cells and other pathogens, the invasive hyphae of A. fumigatus encounters hypoxic (low oxygen levels, ≤ 1%) micro-environments at the site of infection in the host organism. [17] [18] [19] Current research suggests that upon infection, necrosis and inflammation cause tissue damage which decreases available oxygen concentrations due to a local reduction in perfusion, the passaging of fluids to organs. In A. fumigatus specifically, secondary metabolites have been found to inhibit the development of new blood vessels leading to tissue damage, the inhibition of tissue repair, and ultimately localized hypoxic micro-environments. [18] The exact implications of hypoxia on fungal pathogenesis is currently unknown, however these low oxygen environments have long been associated with negative clinical outcomes. Due to the significant correlations identified between hypoxia, fungal infections, and negative clinical outcomes, the mechanisms by which A. fumigatus adapts in hypoxia is a growing area of focus for novel drug targets.

Two highly characterized sterol-regulatory element binding proteins, SrbA and SrbB, along with their processing pathways, have been shown to impact the fitness of A. fumigatus in hypoxic conditions. The transcription factor SrbA is the master regulator in the fungal response to hypoxia in vivo and is essential in many biological processes including iron homeostasis, antifungal azole drug resistance, and virulence. [20] Consequently, the loss of SrbA results in an inability for A. fumigatus to grow in low iron conditions, a higher sensitivity to anti-fungal azole drugs, and a complete loss of virulence in IPA (invasive pulmonary aspergillosis) mouse models. [21] SrbA knockout mutants do not show any signs of in vitro growth in low oxygen, which is thought to be associated with the attenuated virulence. SrbA functionality in hypoxia is dependent upon an upstream cleavage process carried out by the proteins RbdB, SppA, and Dsc A-E. [22] [23] [24] SrbA is cleaved from an endoplasmic reticulum residing 1015 amino acid precursor protein to a 381 amino acid functional form. The loss of any of the above SrbA processing proteins results in a dysfunctional copy of SrbA and a subsequent loss of in vitro growth in hypoxia as well as attenuated virulence. Chromatin immunoprecipitation studies with the SrbA protein led to the identification of a second hypoxia regulator, SrbB. [21] Although little is known about the processing of SrbB, this transcription factor has also shown to be a key player in virulence and the fungal hypoxia response. [21] Similar to SrbA, a SrbB knockout mutant resulted in a loss of virulence, however, there was no heightened sensitivity towards antifungal drugs nor a complete loss of growth under hypoxic conditions (50% reduction in SrbB rather than 100% reduction in SrbA). [21] [20] In summary, both SrbA and SrbB have shown to be critical in the adaptation of A. fumigatus in the mammalian host.

Nutrient acquisition

Aspergillus fumigatus must acquire nutrients from its external environment to survive and flourish within its host. Many of the genes involved in such processes have been shown to impact virulence through experiments involving genetic mutation. Examples of nutrient uptake include that of metals, nitrogen, and macromolecules such as peptides. [12] [25]

Iron acquisition

Iron is a necessary cofactor for many enzymes, and can act as a catalyst in the electron transport system. A. fumigatus has two mechanisms for the uptake of iron, reductive iron acquisition and siderophore-mediated. [27] [28] Reductive iron acquisition includes conversion of iron from the ferric (Fe+3) to the ferrous (Fe+2) state and subsequent uptake via FtrA, an iron permease. Targeted mutation of the ftrA gene did not induce a decrease in virulence in the murine model of A. fumigatus invasion. In contrast, targeted mutation of sidA, the first gene in the siderophore biosynthesis pathway, proved siderophore-mediated iron uptake to be essential for virulence. [28] [29] Mutation of the downstream siderophore biosynthesis genes sidC, sidD, sidF and sidG resulted in strains of A. fumigatus with similar decreases in virulence. [26] These mechanisms of iron uptake appear to work in parallel and both are upregulated in response to iron starvation. [28]

Nitrogen assimilation

Aspergillus fumigatus can survive on a variety of different nitrogen sources, and the assimilation of nitrogen is of clinical importance, as it has been shown to affect virulence. [25] [30] Proteins involved in nitrogen assimilation are transcriptionally regulated by the AfareA gene in A. fumigatus. Targeted mutation of the afareA gene showed a decrease in onset of mortality in a mouse model of invasion. [30] The Ras regulated protein RhbA has also been implicated in nitrogen assimilation. RhbA was found to be transcriptionally upregulated following contact of A. fumigatus with human endothelial cells, and strains with targeted mutation of the rhbA gene showed decreased growth on poor nitrogen sources and reduced virulence in vivo. [31]

Proteinases

The human lung contains large quantities of collagen and elastin, proteins that allow for tissue flexibility. [32] Aspergillus fumigatus produces and secretes elastases, proteases that cleave elastin in order to break down these macromolecular polymers for uptake. A significant correlation between the amount of elastase production and tissue invasion was first discovered in 1984. [33] Clinical isolates have also been found to have greater elastase activity than environmental strains of A. fumigatus. [34] A number of elastases have been characterized, including those from the serine protease, aspartic protease, and metalloprotease families. [35] [36] [37] [38] Yet, the large redundancy of these elastases has hindered the identification of specific effects on virulence. [12] [25]

Unfolded protein response

A number of studies found that the unfolded protein response contributes to virulence of A. fumigatus. [39]

Secondary metabolism

Secondary metabolites in fungal development

The lifecycle of filamentous fungi including Aspergillus spp. consists of two phases: a hyphal growth phase and a reproductive ( sporulation) phase. The switch between growth and reproductive phases of these fungi is regulated in part by the level of secondary metabolite production. [41] [42] The secondary metabolites are believed to be produced to activate sporulation and pigments required for sporulation structures. [43] G protein signaling regulates secondary metabolite production. [44] Genome sequencing has revealed 40 potential genes involved in secondary metabolite production including mycotoxins, which are produced at the time of sporulation. [9] [45]

Gliotoxin

Gliotoxin is a mycotoxin capable of altering host defenses through immunosuppression. Neutrophils are the principal targets of gliotoxin. [46] [47] Gliotoxin interrupts the function of leukocytes by inhibiting migration and superoxide production and causes apoptosis in macrophages. [48] Gliotoxin disrupts the proinflammatory response through inhibition of NF-κB. [49]

Transcriptional regulation of gliotoxin

LaeA and GliZ are transcription factors known to regulate the production of gliotoxin. LaeA is a universal regulator of secondary metabolite production in Aspergillus spp. [40] LaeA influences the expression of 9.5% of the A. fumigatus genome, including many secondary metabolite biosynthesis genes such as nonribosomal peptide synthetases. [50] The production of numerous secondary metabolites, including gliotoxin, were impaired in an LaeA mutant (ΔlaeA) strain. [50] The ΔlaeA mutant showed increased susceptibility to macrophage phagocytosis and decreased ability to kill neutrophils ex vivo. [47] LaeA regulated toxins, besides gliotoxin, likely have a role in virulence since loss of gliotoxin production alone did not recapitulate the hypo-virulent ∆laeA pathotype. [50]

Current treatments to combat A. fumigatus infections

Current noninvasive treatments used to combat fungal infections consist of a class of drugs known as azoles. Azole drugs such as voriconazole, itraconazole, and imidazole kill fungi by inhibiting the production of ergosterol—a critical element of fungal cell membranes. Mechanistically, these drugs act by inhibiting the fungal cytochrome p450 enzyme known as 14α-demethylase. [51] However, A. fumigatus resistance to azoles is increasing, potentially due to the use of low levels of azoles in agriculture. [52] [53] The main mode of resistance is through mutations in the cyp51a gene. [54] [55] However, other modes of resistance have been observed accounting for almost 40% of resistance in clinical isolates. [56] [57] [58] Along with azoles, other anti-fungal drug classes do exist such as polyenes and echinocandins.[ citation needed]

Gallery

-

Conidia phialoconidia of A. fumigatus

-

Colony in Petri dish

-

A. fumigatus isolated from woodland soil

-

Slide of an infected turkey brain

See also

References

- ^ Fang W, Latgé JP (August 2018). "Microbe Profile: Aspergillus fumigatus: a saprotrophic and opportunistic fungal pathogen". Microbiology. 164 (8): 1009–1011. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.000651. PMC 6152418. PMID 30066670.

- ^ O'Gorman CM, Fuller H, Dyer PS (January 2009). "Discovery of a sexual cycle in the opportunistic fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus". Nature. 457 (7228): 471–4. Bibcode: 2009Natur.457..471O. doi: 10.1038/nature07528. PMID 19043401. S2CID 4371721.

- ^ Rydholm C, Szakacs G, Lutzoni F (April 2006). "Low genetic variation and no detectable population structure in aspergillus fumigatus compared to closely related Neosartorya species". Eukaryotic Cell. 5 (4): 650–7. doi: 10.1128/EC.5.4.650-657.2006. PMC 1459663. PMID 16607012.

- ^ Dhingra S, Cramer RA (2017). "Regulation of Sterol Biosynthesis in the Human Fungal Pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus: Opportunities for Therapeutic Development". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8: 92. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00092. PMC 5285346. PMID 28203225.

- ^ Abad A, Fernández-Molina JV, Bikandi J, Ramírez A, Margareto J, Sendino J, et al. (December 2010). "What makes Aspergillus fumigatus a successful pathogen? Genes and molecules involved in invasive aspergillosis" (PDF). Revista Iberoamericana de Micologia. 27 (4): 155–82. doi: 10.1016/j.riam.2010.10.003. PMID 20974273.

- ^ Cui CB, Kakeya H, Osada H (August 1996). "Spirotryprostatin B, a novel mammalian cell cycle inhibitor produced by Aspergillus fumigatus". The Journal of Antibiotics. 49 (8): 832–5. doi: 10.7164/antibiotics.49.832. PMID 8823522.

- ^ Nieminen SM, Kärki R, Auriola S, Toivola M, Laatsch H, Laatikainen R, et al. (October 2002). "Isolation and identification of Aspergillus fumigatus mycotoxins on growth medium and some building materials". Applied and Environmental Microbiology. 68 (10): 4871–5. Bibcode: 2002ApEnM..68.4871N. doi: 10.1128/aem.68.10.4871-4875.2002. PMC 126391. PMID 12324333.

- ^ Galagan JE, Calvo SE, Cuomo C, Ma LJ, Wortman JR, Batzoglou S, et al. (December 2005). "Sequencing of Aspergillus nidulans and comparative analysis with A. fumigatus and A. oryzae". Nature. 438 (7071): 1105–15. Bibcode: 2005Natur.438.1105G. doi: 10.1038/nature04341. PMID 16372000.

- ^ a b Nierman WC, Pain A, Anderson MJ, Wortman JR, Kim HS, Arroyo J, et al. (December 2005). "Genomic sequence of the pathogenic and allergenic filamentous fungus Aspergillus fumigatus". Nature. 438 (7071): 1151–6. Bibcode: 2005Natur.438.1151N. doi: 10.1038/nature04332. hdl: 10261/71531. PMID 16372009.

- ^ Machida M, Asai K, Sano M, Tanaka T, Kumagai T, Terai G, et al. (December 2005). "Genome sequencing and analysis of Aspergillus oryzae". Nature. 438 (7071): 1157–61. Bibcode: 2005Natur.438.1157M. doi: 10.1038/nature04300. PMID 16372010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m Ben-Ami R, Lewis RE, Kontoyiannis DP (August 2010). "Enemy of the (immunosuppressed) state: an update on the pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus infection". British Journal of Haematology. 150 (4): 406–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2010.08283.x. PMID 20618330. S2CID 28216163.

- ^ a b c d Hohl TM, Feldmesser M (November 2007). "Aspergillus fumigatus: principles of pathogenesis and host defense". Eukaryotic Cell. 6 (11): 1953–63. doi: 10.1128/EC.00274-07. PMC 2168400. PMID 17890370.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Segal BH (April 2009). "Aspergillosis". The New England Journal of Medicine. 360 (18): 1870–84. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra0808853. PMID 19403905.

- ^ a b c d e f Filler SG, Sheppard DC (December 2006). "Fungal invasion of normally non-phagocytic host cells". PLOS Pathogens. 2 (12): e129. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0020129. PMC 1757199. PMID 17196036.

- ^ Karnam A, Bonam SR, Rambabu N, Wong SS, Aimanianda V, Bayry J (November 16, 2021). "Wnt-β-Catenin Signaling in Human Dendritic Cells Mediates Regulatory T-Cell Responses to Fungi via the PD-L1 Pathway". mBio. 12 (6): e0282421. doi: 10.1128/mBio.02824-21. PMC 8593687. PMID 34781737.

- ^ Stephen-Victor E, Karnam A, Fontaine T, Beauvais A, Das M, Hegde P, Prakhar P, Holla S, Balaji KN, Kaveri SV, Latgé JP, Aimanianda V, Bayry J (December 5, 2017). "Aspergillus fumigatus Cell Wall α-(1,3)-Glucan Stimulates Regulatory T-Cell Polarization by Inducing PD-L1 Expression on Human Dendritic Cells". J Infect Dis. 216 (10): 1281–1294. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jix469. PMID 28968869.

- ^ Grahl N, Cramer RA (February 2010). "Regulation of hypoxia adaptation: an overlooked virulence attribute of pathogenic fungi?". Medical Mycology. 48 (1): 1–15. doi: 10.3109/13693780902947342. PMC 2898717. PMID 19462332.

- ^ a b Grahl N, Shepardson KM, Chung D, Cramer RA (May 2012). "Hypoxia and fungal pathogenesis: to air or not to air?". Eukaryotic Cell. 11 (5): 560–70. doi: 10.1128/EC.00031-12. PMC 3346435. PMID 22447924.

- ^ Wezensky SJ, Cramer RA (April 2011). "Implications of hypoxic microenvironments during invasive aspergillosis". Medical Mycology. 49 (Suppl 1): S120–4. doi: 10.3109/13693786.2010.495139. PMC 2951492. PMID 20560863.

- ^ a b Willger SD, Puttikamonkul S, Kim KH, Burritt JB, Grahl N, Metzler LJ, Barbuch R, Bard M, Lawrence CB, Cramer RA (November 2008). "A sterol-regulatory element binding protein is required for cell polarity, hypoxia adaptation, azole drug resistance, and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus". PLOS Pathogens. 4 (11): e1000200. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000200. PMC 2572145. PMID 18989462.

- ^ a b c d Chung D, Barker BM, Carey CC, Merriman B, Werner ER, Lechner BE, Dhingra S, Cheng C, Xu W, Blosser SJ, Morohashi K, Mazurie A, Mitchell TK, Haas H, Mitchell AP, Cramer RA (November 2014). "ChIP-seq and in vivo transcriptome analyses of the Aspergillus fumigatus SREBP SrbA reveals a new regulator of the fungal hypoxia response and virulence". PLOS Pathogens. 10 (11): e1004487. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004487. PMC 4223079. PMID 25375670.

- ^ Dhingra S, Kowalski CH, Thammahong A, Beattie SR, Bultman KM, Cramer RA (2016). "RbdB, a Rhomboid Protease Critical for SREBP Activation and Virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus". mSphere. 1 (2). doi: 10.1128/mSphere.00035-16. PMC 4863583. PMID 27303716.

- ^ Bat-Ochir C, Kwak JY, Koh SK, Jeon MH, Chung D, Lee YW, Chae SK (May 2016). "The signal peptide peptidase SppA is involved in sterol regulatory element-binding protein cleavage and hypoxia adaptation in Aspergillus nidulans". Molecular Microbiology. 100 (4): 635–55. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13341. PMID 26822492.

- ^ Willger SD, Cornish EJ, Chung D, Fleming BA, Lehmann MM, Puttikamonkul S, Cramer RA (December 2012). "Dsc orthologs are required for hypoxia adaptation, triazole drug responses, and fungal virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus". Eukaryotic Cell. 11 (12): 1557–67. doi: 10.1128/EC.00252-12. PMC 3536281. PMID 23104569.

- ^ a b c Dagenais TR, Keller NP (July 2009). "Pathogenesis of Aspergillus fumigatus in Invasive Aspergillosis". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 22 (3): 447–65. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00055-08. PMC 2708386. PMID 19597008.

- ^ a b Schrettl M, Bignell E, Kragl C, Sabiha Y, Loss O, Eisendle M, et al. (September 2007). "Distinct roles for intra- and extracellular siderophores during Aspergillus fumigatus infection". PLOS Pathogens. 3 (9): 1195–207. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030128. PMC 1971116. PMID 17845073.

- ^ Haas H (September 2003). "Molecular genetics of fungal siderophore biosynthesis and uptake: the role of siderophores in iron uptake and storage". Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology. 62 (4): 316–30. doi: 10.1007/s00253-003-1335-2. PMID 12759789. S2CID 10989925.

- ^ a b c Schrettl M, Bignell E, Kragl C, Joechl C, Rogers T, Arst HN, et al. (November 2004). "Siderophore biosynthesis but not reductive iron assimilation is essential for Aspergillus fumigatus virulence". The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 200 (9): 1213–9. doi: 10.1084/jem.20041242. PMC 2211866. PMID 15504822.

- ^ Hissen AH, Wan AN, Warwas ML, Pinto LJ, Moore MM (September 2005). "The Aspergillus fumigatus siderophore biosynthetic gene sidA, encoding L-ornithine N5-oxygenase, is required for virulence". Infection and Immunity. 73 (9): 5493–503. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.9.5493-5503.2005. PMC 1231119. PMID 16113265.

- ^ a b Hensel M, Arst HN, Aufauvre-Brown A, Holden DW (June 1998). "The role of the Aspergillus fumigatus areA gene in invasive pulmonary aspergillosis". Molecular & General Genetics. 258 (5): 553–7. doi: 10.1007/s004380050767. PMID 9669338. S2CID 27753283.

- ^ Panepinto JC, Oliver BG, Amlung TW, Askew DS, Rhodes JC (August 2002). "Expression of the Aspergillus fumigatus rheb homologue, rhbA, is induced by nitrogen starvation". Fungal Genetics and Biology. 36 (3): 207–14. doi: 10.1016/S1087-1845(02)00022-1. PMID 12135576.

- ^ Rosenbloom J (December 1984). "Elastin: relation of protein and gene structure to disease". Laboratory Investigation; A Journal of Technical Methods and Pathology. 51 (6): 605–23. PMID 6150137.

- ^ Kothary MH, Chase T, Macmillan JD (January 1984). "Correlation of elastase production by some strains of Aspergillus fumigatus with ability to cause pulmonary invasive aspergillosis in mice". Infection and Immunity. 43 (1): 320–5. doi: 10.1128/IAI.43.1.320-325.1984. PMC 263429. PMID 6360904.

- ^ Blanco JL, Hontecillas R, Bouza E, Blanco I, Pelaez T, Muñoz P, et al. (May 2002). "Correlation between the elastase activity index and invasiveness of clinical isolates of Aspergillus fumigatus". Journal of Clinical Microbiology. 40 (5): 1811–3. doi: 10.1128/JCM.40.5.1811-1813.2002. PMC 130931. PMID 11980964.

- ^ Reichard U, Büttner S, Eiffert H, Staib F, Rüchel R (December 1990). "Purification and characterisation of an extracellular serine proteinase from Aspergillus fumigatus and its detection in tissue". Journal of Medical Microbiology. 33 (4): 243–51. doi: 10.1099/00222615-33-4-243. PMID 2258912.

- ^ Markaryan A, Morozova I, Yu H, Kolattukudy PE (June 1994). "Purification and characterization of an elastinolytic metalloprotease from Aspergillus fumigatus and immunoelectron microscopic evidence of secretion of this enzyme by the fungus invading the murine lung". Infection and Immunity. 62 (6): 2149–57. doi: 10.1128/IAI.62.6.2149-2157.1994. PMC 186491. PMID 8188335.

- ^ Lee JD, Kolattukudy PE (October 1995). "Molecular cloning of the cDNA and gene for an elastinolytic aspartic proteinase from Aspergillus fumigatus and evidence of its secretion by the fungus during invasion of the host lung". Infection and Immunity. 63 (10): 3796–803. doi: 10.1128/IAI.63.10.3796-3803.1995. PMC 173533. PMID 7558282.

- ^ Iadarola P, Lungarella G, Martorana PA, Viglio S, Guglielminetti M, Korzus E, et al. (1998). "Lung injury and degradation of extracellular matrix components by Aspergillus fumigatus serine proteinase". Experimental Lung Research. 24 (3): 233–51. doi: 10.3109/01902149809041532. PMID 9635248.

- ^ Feng X, Krishnan K, Richie DL, Aimanianda V, Hartl L, Grahl N, et al. (October 2011). "HacA-independent functions of the ER stress sensor IreA synergize with the canonical UPR to influence virulence traits in Aspergillus fumigatus". PLOS Pathogens. 7 (10): e1002330. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002330. PMC 3197630. PMID 22028661.

- ^ a b Bok JW, Keller NP (April 2004). "LaeA, a regulator of secondary metabolism in Aspergillus spp". Eukaryotic Cell. 3 (2): 527–35. doi: 10.1128/EC.3.2.527-535.2004. PMC 387652. PMID 15075281.

- ^ Calvo AM, Wilson RA, Bok JW, Keller NP (September 2002). "Relationship between secondary metabolism and fungal development". Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 66 (3): 447–59, table of contents. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.66.3.447-459.2002. PMC 120793. PMID 12208999.

- ^ Tao L, Yu JH (February 2011). "AbaA and WetA govern distinct stages of Aspergillus fumigatus development". Microbiology. 157 (Pt 2): 313–26. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.044271-0. PMID 20966095.

- ^ Adams TH, Yu JH (December 1998). "Coordinate control of secondary metabolite production and asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans". Current Opinion in Microbiology. 1 (6): 674–7. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5274(98)80114-8. PMID 10066549.

- ^ Brodhagen M, Keller NP (July 2006). "Signalling pathways connecting mycotoxin production and sporulation". Molecular Plant Pathology. 7 (4): 285–301. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2006.00338.x. PMID 20507448.

- ^ Trail F, Mahanti N, Linz J (April 1995). "Molecular biology of aflatoxin biosynthesis". Microbiology. 141 (4): 755–65. doi: 10.1099/13500872-141-4-755. PMID 7773383.

- ^ Spikes S, Xu R, Nguyen CK, Chamilos G, Kontoyiannis DP, Jacobson RH, et al. (February 2008). "Gliotoxin production in Aspergillus fumigatus contributes to host-specific differences in virulence". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 197 (3): 479–86. doi: 10.1086/525044. PMID 18199036.

- ^ a b Bok JW, Chung D, Balajee SA, Marr KA, Andes D, Nielsen KF, et al. (December 2006). "GliZ, a transcriptional regulator of gliotoxin biosynthesis, contributes to Aspergillus fumigatus virulence". Infection and Immunity. 74 (12): 6761–8. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00780-06. PMC 1698057. PMID 17030582.

- ^ Kamei K, Watanabe A (May 2005). "Aspergillus mycotoxins and their effect on the host". Medical Mycology. 43 (Suppl 1): S95-9. doi: 10.1080/13693780500051547. PMID 16110799.

- ^ Gardiner DM, Waring P, Howlett BJ (April 2005). "The epipolythiodioxopiperazine (ETP) class of fungal toxins: distribution, mode of action, functions and biosynthesis". Microbiology. 151 (Pt 4): 1021–1032. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.27847-0. PMID 15817772.

- ^ a b c Perrin RM, Fedorova ND, Bok JW, Cramer RA, Wortman JR, Kim HS, et al. (April 2007). "Transcriptional regulation of chemical diversity in Aspergillus fumigatus by LaeA". PLOS Pathogens. 3 (4): e50. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030050. PMC 1851976. PMID 17432932.

- ^ Panackal AA, Bennett JE, Williamson PR (September 2014). "Treatment options in Invasive Aspergillosis". Current Treatment Options in Infectious Diseases. 6 (3): 309–325. doi: 10.1007/s40506-014-0016-2. PMC 4200583. PMID 25328449.

- ^ Berger S, El Chazli Y, Babu AF, Coste AT (2017-06-07). "Aspergillus fumigatus: A Consequence of Antifungal Use in Agriculture?". Frontiers in Microbiology. 8: 1024. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01024. PMC 5461301. PMID 28638374.

- ^ Bueid A, Howard SJ, Moore CB, Richardson MD, Harrison E, Bowyer P, Denning DW (October 2010). "Azole antifungal resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus: 2008 and 2009". The Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. 65 (10): 2116–8. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq279. PMID 20729241.

- ^ Nash A, Rhodes J (April 2018). "Simulations of CYP51A from Aspergillus fumigatus in a model bilayer provide insights into triazole drug resistance". Medical Mycology. 56 (3): 361–373. doi: 10.1093/mmy/myx056. PMC 5895076. PMID 28992260.

- ^ Snelders E, Karawajczyk A, Schaftenaar G, Verweij PE, Melchers WJ (June 2010). "Azole resistance profile of amino acid changes in Aspergillus fumigatus CYP51A based on protein homology modeling". Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy. 54 (6): 2425–30. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01599-09. PMC 2876375. PMID 20385860.

- ^ Rybak JM, Ge W, Wiederhold NP, Parker JE, Kelly SL, Rogers PD, Fortwendel JR (April 2019). Alspaugh JA (ed.). "hmg1, Challenging the Paradigm of Clinical Triazole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus". mBio. 10 (2): e00437–19, /mbio/10/2/mBio.00437–19.atom. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00437-19. PMC 6445940. PMID 30940706.

- ^ Camps SM, Dutilh BE, Arendrup MC, Rijs AJ, Snelders E, Huynen MA, et al. (2012-11-30). "Discovery of a HapE mutation that causes azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus through whole genome sequencing and sexual crossing". PLOS ONE. 7 (11): e50034. Bibcode: 2012PLoSO...750034C. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0050034. PMC 3511431. PMID 23226235.

- ^ Furukawa T, van Rhijn N, Fraczek M, Gsaller F, Davies E, Carr P, et al. (January 2020). "The negative cofactor 2 complex is a key regulator of drug resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus". Nature Communications. 11 (1): 427. Bibcode: 2020NatCo..11..427F. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-14191-1. PMC 7194077. PMID 31969561.

External links

- Emergence of Azole Resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus and Spread of a Single Resistance Mechanism. at SciVee

- The Aspergillus Trust A registered UK charity engaged in support of people with aspergillus disease worldwide and research into cures

- The Fungal Research Trust

- Aspergillus info from DoctorFungus.org