"Reflections on Gandhi" is an essay by George Orwell, first published in 1949, which responds to Mahatma Gandhi's autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth. The essay, which appeared in the American magazine Partisan Review, discusses the autobiography and offers both praise and criticism to Gandhi, focusing in particular on the effectiveness of Gandhian nonviolence and the tension between Gandhi's spiritual worldview and his political activities. One of a number of essays written by Orwell and published between Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), "Reflections on Gandhi" was the last of Orwell's essays to be published in his lifetime and was not republished until after his death.

Background

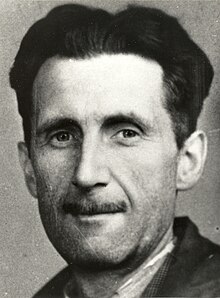

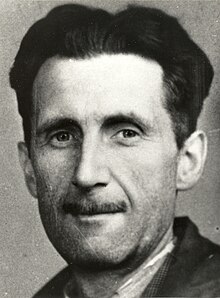

George Orwell was born in Motihari, Bihar, in 1903, and lived there for a year. [1] As a young man he worked for the Indian Imperial Police in the province of Burma, then part of British India, from 1922 until 1927. [2] Later he worked for the BBC's Indian Section, writing and producing reviews and commentaries on news for broadcast in India and Southeast Asia from 1941 to 1943. [3] At the BBC, Orwell worked with Balraj Sahni, who had previously lived with Mahatma Gandhi at his ashram in Sevagram. [4]

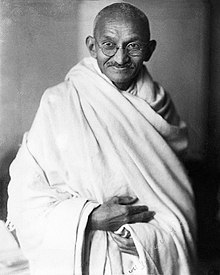

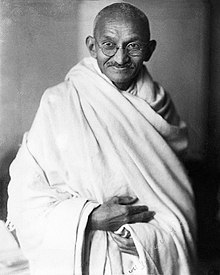

Gandhi's The Story of My Experiments with Truth was first published in serial form in Navajivan from 1925, then translated into English and published as a book in 1927. [5] The book describes Gandhi's childhood, his time spent in London and South Africa, and life in India until the 1920s, with a focus on the author's moral and religious development. [6] The 1948 American edition, published by Public Affairs Press, was the first edition of the full text to be published outside India. [5]

In August 1948, William Phillips invited Orwell to review The Story of My Experiments with Truth for Partisan Review. [5] Orwell was a regular contributor to Partisan Review, which had been established in 1934 as an organ of the Communist Party USA but later became an anti-Communist publication. [7] [8] His contributions between 1941 and 1946 included a number of " London Letters" discussing the Second World War, as well as pieces on politics more broadly and the London literary milieu. [7] [8] Orwell had become well known in the United States after the publication of Animal Farm in 1946. [8]

Orwell had previously written about Gandhi in a number of letters and book reviews, and in his " As I Please" column in Tribune in 1944. [9] In his review of Beverley Nichols' Verdict on India, Orwell defended Gandhi from Nichols' attacks, though in a 1948 letter to Julian Symons he acknowledge he harboured "dark suspicions about Gandhi". [10]

Composition and publication

Orwell quickly accepted Phillips' invitation, writing the essay in late 1948 while revising Nineteen Eighty-Four, and the review was published in January 1949. [11] [12] "Reflections on Gandhi" was one of a number of essays by Orwell published in the years between the publication of Animal Farm in 1945 and Nineteen Eighty-Four in 1949; others include " Notes on Nationalism", " Politics and the English Language", " Why I Write", " The Prevention of Literature" and " Some Thoughts on the Common Toad". [13] "Reflections on Gandhi" was Orwell's last published essay. [14] [15]

In "Reflections", Orwell draws on points he had previously made in a review of Louis Fischer's Gandhi and Stalin (1947), on the question of Gandhi's perspective on the Holocaust and the possible efficacy of Gandhian tactics in a society like that of the Soviet Union. [16] While the essay draws on themes from his earlier writing on Gandhi, in "Reflections" he also offers a more developed perspective on Gandhi and responds to the problems posed by the post-war world. [5] Descriptions of Gandhi as a saintlike figure, which Orwell addresses in the essay, had been advanced by British and American clergymen including John Haynes Holmes and literary figures including the French author Romain Rolland. [17]

Gita V. Pai suggests that Orwell took the title of "Reflections on Gandhi" from Georges Sorel's Reflections on Violence (1908), which Pai suggests may also have influenced Nineteen Eighty-Four; Pai also suggests that Orwell may have seen connections between Gandhi's use of political symbolism and imagery, and Sorel's argument for the necessity of symbolism and mythology in politics. [18] Alex Woloch, meanwhile, suggests the title—and similar titles, including " Some Thoughts on the Common Toad", " Second Thoughts on James Burnham" and Notes on Nationalism—indicates the importance of the process of thinking, or reflecting, in Orwell's work, and serves "to divide the focus between process and object, means and end". [19]

"Reflections on Gandhi" was not included in Inside the Whale and Other Essays (1940) or Critical Essays (1946), the two volumes of Orwell's essays published in his lifetime, and so remained difficult to find and little-read at the time of his death. [20] In 1949, the Ministry of Information (MOI) obtained permission to print "Reflections on Gandhi" in its Indian publication Mirror. [21] The essay was edited by the MOI with the intention of improving Anglo-Indian relations. [21] In August 1949, months before Orwell's death, he wrote to Fredric Warburg with a proposal for a new collection of essays, in which "Reflections on Gandhi" would be reprinted alongside " Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool", "Politics and the English Language", " Shooting an Elephant", " How the Poor Die", and planned essays on Joseph Conrad and George Gissing. [22]

Overview

Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent, but the tests that have to be applied to them are not, of course, the same in all cases. In Gandhi's case the questions one feels inclined to ask are: to what extent was Gandhi moved by vanity—by the consciousness of himself as a humble, naked old man, sitting on a praying mat and shaking empires by sheer spiritual power—and to what extent did he compromise his own principles by entering politics, which of their nature are inseparable from coercion and fraud? To give a definite answer one would have to study Gandhi's acts and writings in immense detail, for his whole life was a sort of pilgrimage in which every act was significant.

George Orwell, "Reflections on Gandhi" [23]

Orwell introduces The Story of My Experiments with Truth as evidence for a positive appraisal of Gandhi's life, due in part to its focus on Gandhi's life before his involvement in politics, which Orwell finds indicative of Gandhi's shrewdness and intelligence. [23] Orwell recalls reading the autobiography in is original serialised form, and finding that it challenged his preconceptions about Gandhi as not posing a threat to British rule. [23] Orwell notes Gandhi's admirable and upstanding qualities. [24] Orwell also observes that Gandhi's political views developed only slowly, and that, as a result, much of the book describes commonplace experiences. [23]

Rejecting claims by western anarchists and pacifists to claim Gandhi as an adherent to their views, Orwell argues that Gandhi's thought presupposes religious faith and is incompatible with a secular worldview. [25] Turning to Gandhi's asceticism, Orwell finds his views "inhuman" insofar as human existence, Orwell argues, always involves compromise between one's beliefs and one's relationships with others. [26] Discussing Gandhi's pacifism, Orwell praises him for not evading difficult questions such as those surrounding the Holocaust, but notes that a Gandhian political strategy requires the existence of civil rights, and suggests it would not be successful in a totalitarian society. [27] Considering the perceived likelihood of a Third World War, Orwell acknowledges that nonviolence may be necessary, and finds that, although he feels "a sort of aesthetic distaste for Gandhi", he was nonetheless largely politically in the right and politically successful. [28]

Critical responses

In a 1982 article, Shamsul Islam argues that "Reflections on Gandhi" indicates that Orwell, by the late 1940s, found British imperialism a mild form of tyranny compared to that found in totalitarian states, and even to a degree admired it. [29] Also in 1982, Laraine Fergenson finds that Orwell's dichotomy separating Gandhian "other-worldly" commitments and Western humanism is complicated by religious figures such as Daniel Berrigan who have campaigned for political reform on the basis of their religious convictions. [30]

Lydia Fakundiny distinguishes "Reflections" from Orwell's essays " Shooting an Elephant" and " A Hanging", arguing that while those earlier essays present carefully-crafted narratives drawn from personal experience, "Reflections" is a more forthright statement of the author's views. [31] Fakundiny characterises the essay as the product of:

a whole mind revealing its energetic complexity, one mind resisting the conventional, the orthodox, the reductive view of its subject, a mind capacious and supple enough to honor the political achievements of a man whose basic values it dismantles and rejects. [31]

In a 2003 essay in The New Yorker, Louis Menand described "Reflections on Gandhi" as "a grudging piece of writing" and suggested that the successful use of nonviolent resistance by Martin Luther King Jr. indicated that Orwell was wrong to doubt the tactic's effectiveness. [32] Ian Williams rejects Menand's conclusions, finding his assessment of Gandhi to be "inflated" and the essay to be "a well-balanced appreciation". [33]

Lawrence Rosenwald argues that "Reflections on Gandhi" constitutes the culmination of the transformation of Orwell's views on Gandhi "from harsh to almost sentimental", a transformation he suggests may have resulted from a change in Orwell's mood following the end of World War II, from India's independence, or from his re-reading of Gandhi's autobiography. [34] Rosenwald describes the essay as "one of the sanest, most challenging, and most generous essays" about Gandhi, [34] and suggests that key to the essay's strength is Orwell's suggestion that Gandhi's pacifism can be separated from his broader views and practices. [35] Rosenwald suggests that the essay reveals the personal quality of Orwell's critique of pacifism: his tendency to find pacifism worthy of consideration when articulated by pacifists such as Gandhi, who he respects, but not when defended by those he does not respect. [36] Rosenwald takes "Reflections on Gandhi" as a contemplation of "the idea that certain nonviolent practices can be formidably resistant, as uncompromising as battle", which would be articulated in later work by Denise Levertov and Gene Sharp. [37]

In his study of the essay form, G. Douglas Atkins describes "Reflections" as "a supreme instance of essaying." [38] Atkins identifies the question of truth as Orwell's abiding concern in the essay, as indicated by its opening statement on sainthood. [38] Atkins situates Orwell's argument, in particular his rejection of Gandhi's spirituality, as the culmination of a tradition of essay-writing inaugurated by Michel de Montaigne. [39] Atkins contends, however, that the distinction Orwell draws between Gandhian spirituality and the necessities of politics is a false dichotomy, and that religious commitments can in fact emerge from quotidian life. [39]

Peter Marks argues that "Reflections on Gandhi"'s opening phrase recalls the argument of Orwell's earlier essay " Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool", which likened Leo Tolstoy to Gandhi. [40] Marks finds that, for Orwell, Gandhi is a more complex and compelling figure than Tolstoy due to his combination of spiritual sentiment and political astuteness. [15] In Marks' estimation, "Reflections on Gandhi" offers an intervention on global politics through an "astute if contestable" interpretation of the figure of Gandhi. [41]

In a 2011 article, Ioana Nan describes the positions articulated by Orwell in "Reflections on Gandhi" as those of "a skeptical Westerner" attentive to the possibility that Gandhi was used by British imperialists for their own gain. [42] Nan compares Orwell's views on Gandhi to those of Aldous Huxley, whose essay Notes on Gandhi was published in 1948. [43] Nonetheless, the two authors did agree, Nan suggests, that Gandhi was more pragmatic and practical, and less idealistic, than was commonly thought. [43]

Gita V. Pai argues that in "Reflections on Gandhi" Orwell tempered his earlier hostility to pacifism, a topic on which he had criticised Gandhi in the early 1940s. [44] While Orwell rejected Gandhian pacifism during the Second World War, Pai argues, by 1949 (after India's independence and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) he had come to see satyagraha as preferable to western leftists' version of pacifism. [45] Pai suggests that the contradiction between claims for Gandhi's saintliness and the reality of his political shrewdness may be understood in terms of doublethink, a term Orwell coined in Nineteen Eighty-Four to refer to the simultaneous adherence to contrary beliefs. [46]

In Orwell's Roses, Rebecca Solnit argues that "Reflections on Gandhi" recapitulates some of the guiding ideas of Nineteen Eighty-Four, such as a rejection of "inflexible absolutism". Solnit argues that Orwell characterises Gandhi's asceticism as approximate to "ideological fanaticism", but suggests Orwell's interpretation of Gandhi's thought may be inaccurate. [47]

See also

Notes

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 56.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 56–7.

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Pai 2014, p. 53.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 53–4.

- ^ a b Nan 2011, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Pai 2014, p. 54.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 58–61, 64–6, 70–1.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 54, 57, 72.

- ^ Davison 1996, p. xxvi.

- ^ Marks 2011, pp. 135–6.

- ^ Hammond 1982, p. 187.

- ^ a b Marks 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 66–8.

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 72.

- ^ Woloch 2016, p. 46.

- ^ Marks 2011, pp. 3–4, 187.

- ^ a b Davison 1996, p. 107.

- ^ Davison 1996, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d Orwell 1968, p. 523.

- ^ Orwell 1968, pp. 524–5.

- ^ Orwell 1968, p. 526.

- ^ Orwell 1968, pp. 526–8.

- ^ Orwell 1968, pp. 528–30.

- ^ Orwell 1968, pp. 530–1.

- ^ Islam 1982, p. 346.

- ^ Fergenson 1982, p. 103.

- ^ a b Fakundiny 1991, p. 297.

- ^ Menand 2003.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 54.

- ^ a b Rosenwald 2004, p. 118.

- ^ Rosenwald 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Rosenwald 2004, pp. 119–20.

- ^ Rosenwald 2004, p. 120.

- ^ a b Atkins 2008, p. 182.

- ^ a b Atkins 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Marks 2011, p. 180.

- ^ Marks 2011, pp. 188–9.

- ^ Nan 2011, p. 149.

- ^ a b Nan 2011, p. 151.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 61–2.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 61–2, 71.

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 70.

- ^ Solnit 2021, p. 263.

References

- Atkins, G. Douglas (2008). Reading Essays: An Invitation. University of Georgia Press.

- Davison, Peter (1996). George Orwell: A Literary Life. Palgrave. doi: 10.1057/9780230371408. ISBN 978-0-333-54158-6.

- Fakundiny, Lydia, ed. (1991). The Art of the Essay. Houghton Mifflin.

- Fergenson, Laraine (1982). "Thoreau, Daniel Berrigan, and the Problem of Transcendental Politics". Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 65 (1): 103–122. JSTOR 41178203.

- Hammond, J. R. (1982). A George Orwell Companion: A Guide to the Novels, Documentaries and Essays. St. Martin's Press.

- Islam, Shamsul (1982). "George Orwell and the Raj". World Literature Written in English. 21 (2): 341–347. doi: 10.1080/17449858208588733.

- Marks, Peter (2011). George Orwell the Essayist: Literature, Politics and the Periodical Culture. Bloomsbury.

- Menand, Louis (19 January 2003). "Honest, Decent, Wrong: The Invention of George Orwell". The New Yorker. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Nan, Ioana (2011). "Orwell and the Challenge of Subjective Journalism". Lingua: Language and Culture. X (2): 145–52.

- Orwell, George (1968) [1949]. "Reflections on Gandhi". In Orwell, Sonia; Angus, Ian (eds.). The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Volume IV: In Front of Your Nose 1945–1950. Penguin Books. pp. 523–531.

- Pai, Gita V. (2014). "Orwell's Reflections on Saint Gandhi" (PDF). Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies. 40 (1): 51–77. doi: 10.6240/concentric.lit.2014.40.1.04.

- Rosenwald, Lawrence (2004). "Orwell, Pacifism, Pacifists". In Cushman, Thomas; Rodden, John (eds.). George Orwell: Into the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. pp. 111–125.

- Solnit, Rebecca (2021). Orwell's Roses. Granta.

- Williams, Ian (2004). "In Defence of Comrade Psmith: The Orwellian Treatment of Orwell". In Cushman, Thomas; Rodden, John (eds.). George Orwell: Into the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. pp. 45–62.

- Woloch, Alex (2016). Or Orwell: Writing and Democratic Socialism. Harvard University Press.

External links

"Reflections on Gandhi" is an essay by George Orwell, first published in 1949, which responds to Mahatma Gandhi's autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth. The essay, which appeared in the American magazine Partisan Review, discusses the autobiography and offers both praise and criticism to Gandhi, focusing in particular on the effectiveness of Gandhian nonviolence and the tension between Gandhi's spiritual worldview and his political activities. One of a number of essays written by Orwell and published between Animal Farm (1945) and Nineteen Eighty-Four (1949), "Reflections on Gandhi" was the last of Orwell's essays to be published in his lifetime and was not republished until after his death.

Background

George Orwell was born in Motihari, Bihar, in 1903, and lived there for a year. [1] As a young man he worked for the Indian Imperial Police in the province of Burma, then part of British India, from 1922 until 1927. [2] Later he worked for the BBC's Indian Section, writing and producing reviews and commentaries on news for broadcast in India and Southeast Asia from 1941 to 1943. [3] At the BBC, Orwell worked with Balraj Sahni, who had previously lived with Mahatma Gandhi at his ashram in Sevagram. [4]

Gandhi's The Story of My Experiments with Truth was first published in serial form in Navajivan from 1925, then translated into English and published as a book in 1927. [5] The book describes Gandhi's childhood, his time spent in London and South Africa, and life in India until the 1920s, with a focus on the author's moral and religious development. [6] The 1948 American edition, published by Public Affairs Press, was the first edition of the full text to be published outside India. [5]

In August 1948, William Phillips invited Orwell to review The Story of My Experiments with Truth for Partisan Review. [5] Orwell was a regular contributor to Partisan Review, which had been established in 1934 as an organ of the Communist Party USA but later became an anti-Communist publication. [7] [8] His contributions between 1941 and 1946 included a number of " London Letters" discussing the Second World War, as well as pieces on politics more broadly and the London literary milieu. [7] [8] Orwell had become well known in the United States after the publication of Animal Farm in 1946. [8]

Orwell had previously written about Gandhi in a number of letters and book reviews, and in his " As I Please" column in Tribune in 1944. [9] In his review of Beverley Nichols' Verdict on India, Orwell defended Gandhi from Nichols' attacks, though in a 1948 letter to Julian Symons he acknowledge he harboured "dark suspicions about Gandhi". [10]

Composition and publication

Orwell quickly accepted Phillips' invitation, writing the essay in late 1948 while revising Nineteen Eighty-Four, and the review was published in January 1949. [11] [12] "Reflections on Gandhi" was one of a number of essays by Orwell published in the years between the publication of Animal Farm in 1945 and Nineteen Eighty-Four in 1949; others include " Notes on Nationalism", " Politics and the English Language", " Why I Write", " The Prevention of Literature" and " Some Thoughts on the Common Toad". [13] "Reflections on Gandhi" was Orwell's last published essay. [14] [15]

In "Reflections", Orwell draws on points he had previously made in a review of Louis Fischer's Gandhi and Stalin (1947), on the question of Gandhi's perspective on the Holocaust and the possible efficacy of Gandhian tactics in a society like that of the Soviet Union. [16] While the essay draws on themes from his earlier writing on Gandhi, in "Reflections" he also offers a more developed perspective on Gandhi and responds to the problems posed by the post-war world. [5] Descriptions of Gandhi as a saintlike figure, which Orwell addresses in the essay, had been advanced by British and American clergymen including John Haynes Holmes and literary figures including the French author Romain Rolland. [17]

Gita V. Pai suggests that Orwell took the title of "Reflections on Gandhi" from Georges Sorel's Reflections on Violence (1908), which Pai suggests may also have influenced Nineteen Eighty-Four; Pai also suggests that Orwell may have seen connections between Gandhi's use of political symbolism and imagery, and Sorel's argument for the necessity of symbolism and mythology in politics. [18] Alex Woloch, meanwhile, suggests the title—and similar titles, including " Some Thoughts on the Common Toad", " Second Thoughts on James Burnham" and Notes on Nationalism—indicates the importance of the process of thinking, or reflecting, in Orwell's work, and serves "to divide the focus between process and object, means and end". [19]

"Reflections on Gandhi" was not included in Inside the Whale and Other Essays (1940) or Critical Essays (1946), the two volumes of Orwell's essays published in his lifetime, and so remained difficult to find and little-read at the time of his death. [20] In 1949, the Ministry of Information (MOI) obtained permission to print "Reflections on Gandhi" in its Indian publication Mirror. [21] The essay was edited by the MOI with the intention of improving Anglo-Indian relations. [21] In August 1949, months before Orwell's death, he wrote to Fredric Warburg with a proposal for a new collection of essays, in which "Reflections on Gandhi" would be reprinted alongside " Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool", "Politics and the English Language", " Shooting an Elephant", " How the Poor Die", and planned essays on Joseph Conrad and George Gissing. [22]

Overview

Saints should always be judged guilty until they are proved innocent, but the tests that have to be applied to them are not, of course, the same in all cases. In Gandhi's case the questions one feels inclined to ask are: to what extent was Gandhi moved by vanity—by the consciousness of himself as a humble, naked old man, sitting on a praying mat and shaking empires by sheer spiritual power—and to what extent did he compromise his own principles by entering politics, which of their nature are inseparable from coercion and fraud? To give a definite answer one would have to study Gandhi's acts and writings in immense detail, for his whole life was a sort of pilgrimage in which every act was significant.

George Orwell, "Reflections on Gandhi" [23]

Orwell introduces The Story of My Experiments with Truth as evidence for a positive appraisal of Gandhi's life, due in part to its focus on Gandhi's life before his involvement in politics, which Orwell finds indicative of Gandhi's shrewdness and intelligence. [23] Orwell recalls reading the autobiography in is original serialised form, and finding that it challenged his preconceptions about Gandhi as not posing a threat to British rule. [23] Orwell notes Gandhi's admirable and upstanding qualities. [24] Orwell also observes that Gandhi's political views developed only slowly, and that, as a result, much of the book describes commonplace experiences. [23]

Rejecting claims by western anarchists and pacifists to claim Gandhi as an adherent to their views, Orwell argues that Gandhi's thought presupposes religious faith and is incompatible with a secular worldview. [25] Turning to Gandhi's asceticism, Orwell finds his views "inhuman" insofar as human existence, Orwell argues, always involves compromise between one's beliefs and one's relationships with others. [26] Discussing Gandhi's pacifism, Orwell praises him for not evading difficult questions such as those surrounding the Holocaust, but notes that a Gandhian political strategy requires the existence of civil rights, and suggests it would not be successful in a totalitarian society. [27] Considering the perceived likelihood of a Third World War, Orwell acknowledges that nonviolence may be necessary, and finds that, although he feels "a sort of aesthetic distaste for Gandhi", he was nonetheless largely politically in the right and politically successful. [28]

Critical responses

In a 1982 article, Shamsul Islam argues that "Reflections on Gandhi" indicates that Orwell, by the late 1940s, found British imperialism a mild form of tyranny compared to that found in totalitarian states, and even to a degree admired it. [29] Also in 1982, Laraine Fergenson finds that Orwell's dichotomy separating Gandhian "other-worldly" commitments and Western humanism is complicated by religious figures such as Daniel Berrigan who have campaigned for political reform on the basis of their religious convictions. [30]

Lydia Fakundiny distinguishes "Reflections" from Orwell's essays " Shooting an Elephant" and " A Hanging", arguing that while those earlier essays present carefully-crafted narratives drawn from personal experience, "Reflections" is a more forthright statement of the author's views. [31] Fakundiny characterises the essay as the product of:

a whole mind revealing its energetic complexity, one mind resisting the conventional, the orthodox, the reductive view of its subject, a mind capacious and supple enough to honor the political achievements of a man whose basic values it dismantles and rejects. [31]

In a 2003 essay in The New Yorker, Louis Menand described "Reflections on Gandhi" as "a grudging piece of writing" and suggested that the successful use of nonviolent resistance by Martin Luther King Jr. indicated that Orwell was wrong to doubt the tactic's effectiveness. [32] Ian Williams rejects Menand's conclusions, finding his assessment of Gandhi to be "inflated" and the essay to be "a well-balanced appreciation". [33]

Lawrence Rosenwald argues that "Reflections on Gandhi" constitutes the culmination of the transformation of Orwell's views on Gandhi "from harsh to almost sentimental", a transformation he suggests may have resulted from a change in Orwell's mood following the end of World War II, from India's independence, or from his re-reading of Gandhi's autobiography. [34] Rosenwald describes the essay as "one of the sanest, most challenging, and most generous essays" about Gandhi, [34] and suggests that key to the essay's strength is Orwell's suggestion that Gandhi's pacifism can be separated from his broader views and practices. [35] Rosenwald suggests that the essay reveals the personal quality of Orwell's critique of pacifism: his tendency to find pacifism worthy of consideration when articulated by pacifists such as Gandhi, who he respects, but not when defended by those he does not respect. [36] Rosenwald takes "Reflections on Gandhi" as a contemplation of "the idea that certain nonviolent practices can be formidably resistant, as uncompromising as battle", which would be articulated in later work by Denise Levertov and Gene Sharp. [37]

In his study of the essay form, G. Douglas Atkins describes "Reflections" as "a supreme instance of essaying." [38] Atkins identifies the question of truth as Orwell's abiding concern in the essay, as indicated by its opening statement on sainthood. [38] Atkins situates Orwell's argument, in particular his rejection of Gandhi's spirituality, as the culmination of a tradition of essay-writing inaugurated by Michel de Montaigne. [39] Atkins contends, however, that the distinction Orwell draws between Gandhian spirituality and the necessities of politics is a false dichotomy, and that religious commitments can in fact emerge from quotidian life. [39]

Peter Marks argues that "Reflections on Gandhi"'s opening phrase recalls the argument of Orwell's earlier essay " Lear, Tolstoy and the Fool", which likened Leo Tolstoy to Gandhi. [40] Marks finds that, for Orwell, Gandhi is a more complex and compelling figure than Tolstoy due to his combination of spiritual sentiment and political astuteness. [15] In Marks' estimation, "Reflections on Gandhi" offers an intervention on global politics through an "astute if contestable" interpretation of the figure of Gandhi. [41]

In a 2011 article, Ioana Nan describes the positions articulated by Orwell in "Reflections on Gandhi" as those of "a skeptical Westerner" attentive to the possibility that Gandhi was used by British imperialists for their own gain. [42] Nan compares Orwell's views on Gandhi to those of Aldous Huxley, whose essay Notes on Gandhi was published in 1948. [43] Nonetheless, the two authors did agree, Nan suggests, that Gandhi was more pragmatic and practical, and less idealistic, than was commonly thought. [43]

Gita V. Pai argues that in "Reflections on Gandhi" Orwell tempered his earlier hostility to pacifism, a topic on which he had criticised Gandhi in the early 1940s. [44] While Orwell rejected Gandhian pacifism during the Second World War, Pai argues, by 1949 (after India's independence and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) he had come to see satyagraha as preferable to western leftists' version of pacifism. [45] Pai suggests that the contradiction between claims for Gandhi's saintliness and the reality of his political shrewdness may be understood in terms of doublethink, a term Orwell coined in Nineteen Eighty-Four to refer to the simultaneous adherence to contrary beliefs. [46]

In Orwell's Roses, Rebecca Solnit argues that "Reflections on Gandhi" recapitulates some of the guiding ideas of Nineteen Eighty-Four, such as a rejection of "inflexible absolutism". Solnit argues that Orwell characterises Gandhi's asceticism as approximate to "ideological fanaticism", but suggests Orwell's interpretation of Gandhi's thought may be inaccurate. [47]

See also

Notes

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 51.

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 56.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 56–7.

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 57.

- ^ a b c d Pai 2014, p. 53.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 53–4.

- ^ a b Nan 2011, p. 148.

- ^ a b c Pai 2014, p. 54.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 58–61, 64–6, 70–1.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 65–66.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 54, 57, 72.

- ^ Davison 1996, p. xxvi.

- ^ Marks 2011, pp. 135–6.

- ^ Hammond 1982, p. 187.

- ^ a b Marks 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 63.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 66–8.

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 72.

- ^ Woloch 2016, p. 46.

- ^ Marks 2011, pp. 3–4, 187.

- ^ a b Davison 1996, p. 107.

- ^ Davison 1996, p. 110.

- ^ a b c d Orwell 1968, p. 523.

- ^ Orwell 1968, pp. 524–5.

- ^ Orwell 1968, p. 526.

- ^ Orwell 1968, pp. 526–8.

- ^ Orwell 1968, pp. 528–30.

- ^ Orwell 1968, pp. 530–1.

- ^ Islam 1982, p. 346.

- ^ Fergenson 1982, p. 103.

- ^ a b Fakundiny 1991, p. 297.

- ^ Menand 2003.

- ^ Williams 2004, p. 54.

- ^ a b Rosenwald 2004, p. 118.

- ^ Rosenwald 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Rosenwald 2004, pp. 119–20.

- ^ Rosenwald 2004, p. 120.

- ^ a b Atkins 2008, p. 182.

- ^ a b Atkins 2008, p. 185.

- ^ Marks 2011, p. 180.

- ^ Marks 2011, pp. 188–9.

- ^ Nan 2011, p. 149.

- ^ a b Nan 2011, p. 151.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 61–2.

- ^ Pai 2014, pp. 61–2, 71.

- ^ Pai 2014, p. 70.

- ^ Solnit 2021, p. 263.

References

- Atkins, G. Douglas (2008). Reading Essays: An Invitation. University of Georgia Press.

- Davison, Peter (1996). George Orwell: A Literary Life. Palgrave. doi: 10.1057/9780230371408. ISBN 978-0-333-54158-6.

- Fakundiny, Lydia, ed. (1991). The Art of the Essay. Houghton Mifflin.

- Fergenson, Laraine (1982). "Thoreau, Daniel Berrigan, and the Problem of Transcendental Politics". Soundings: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 65 (1): 103–122. JSTOR 41178203.

- Hammond, J. R. (1982). A George Orwell Companion: A Guide to the Novels, Documentaries and Essays. St. Martin's Press.

- Islam, Shamsul (1982). "George Orwell and the Raj". World Literature Written in English. 21 (2): 341–347. doi: 10.1080/17449858208588733.

- Marks, Peter (2011). George Orwell the Essayist: Literature, Politics and the Periodical Culture. Bloomsbury.

- Menand, Louis (19 January 2003). "Honest, Decent, Wrong: The Invention of George Orwell". The New Yorker. Retrieved 10 February 2022.

- Nan, Ioana (2011). "Orwell and the Challenge of Subjective Journalism". Lingua: Language and Culture. X (2): 145–52.

- Orwell, George (1968) [1949]. "Reflections on Gandhi". In Orwell, Sonia; Angus, Ian (eds.). The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Volume IV: In Front of Your Nose 1945–1950. Penguin Books. pp. 523–531.

- Pai, Gita V. (2014). "Orwell's Reflections on Saint Gandhi" (PDF). Concentric: Literary and Cultural Studies. 40 (1): 51–77. doi: 10.6240/concentric.lit.2014.40.1.04.

- Rosenwald, Lawrence (2004). "Orwell, Pacifism, Pacifists". In Cushman, Thomas; Rodden, John (eds.). George Orwell: Into the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. pp. 111–125.

- Solnit, Rebecca (2021). Orwell's Roses. Granta.

- Williams, Ian (2004). "In Defence of Comrade Psmith: The Orwellian Treatment of Orwell". In Cushman, Thomas; Rodden, John (eds.). George Orwell: Into the Twenty-First Century. Routledge. pp. 45–62.

- Woloch, Alex (2016). Or Orwell: Writing and Democratic Socialism. Harvard University Press.