| |

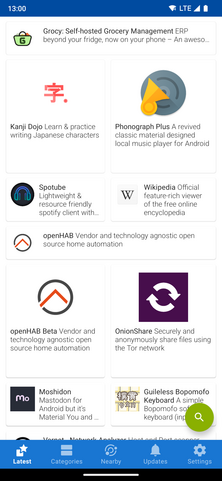

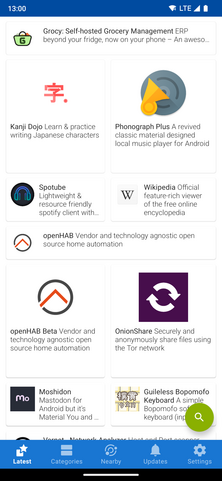

Screenshot of F-Droid 1.19.0 on Android showing the latest apps | |

| Developer(s) | Ciaran Gultnieks

[1]

|

|---|---|

| Initial release | 29 September 2010

[2]

|

| Stable release | 1.17.0

[3]

|

| Repository | |

| Written in | Python (server tools), Jekyll (software) (site), Java (client) |

| Operating system | Android (client), Linux, macOS, Windows 10, FreeBSD (server) |

| Type | Digital distribution of free software, Software repository |

| License | GNU Affero General Public License, version 3.0 or later

[4]

|

| Website |

f-droid |

F-Droid is an open-source app store and software repository for Android, serving a similar function to the Google Play store. The main repository, hosted by the project, contains only free and open source apps. Applications can be browsed, downloaded and installed from the F-Droid website or client app without the need to register for an account. "Anti-features" such as advertising, user tracking, or dependence on non-free software are flagged in app descriptions. [5]

The website also offers the source code of applications it hosts, as well as the software running the F-Droid server, allowing anyone to set up their own app repository. [6] [7] [8]

History

F-Droid was founded by Ciaran Gultnieks in 2010. The client was forked from Aptoide's source code. [10] [11] The project was initially run by the English nonprofit F-Droid Limited. [11] As of 2021, F-Droid Limited was no longer used for donations, [12] and was being shut down, according to spokesman Hans-Cristoph Steiner. [13]

In a 2014 interview for Free Software Foundation, Gultnieks said he was inspired to launch F-Droid because of "lock-down, lock-in and general nefarious behavior from software" on phones. [14]

From 2010 to 2015, F-Droid used the AGPL-licensed Gitorious repository system for development. [15] In 2015, it transitioned to proprietary licensed GitLab [16] when Gitorious was acquired by GitLab. According to Daniel Marti, Former F-Droid Developer, in 2013, removal of AdAway from the Google Play Store caused a spike in searches and downloads of F-Droid, and he estimated there were 30 to 40 thousand users. [17]

Replicant, a fully free software Android operating system, previously used F-Droid as its default and recommended app store. [18] [19] In 2016, the Replicant project determined F-Droid did not comply with GNU Free System Distribution Guidelines, and asked for assistance correcting it, but progress stalled. [20] In June 2022, Replicant announced they had removed F-Droid. [21]

Guardian Project, a suite of free and secure Android applications, started running their own F-Droid repository in early 2012. [22] In 2012, Free Software Foundation Europe featured F-Droid in their Free Your Android! campaign to raise awareness of the privacy and security risks of proprietary software. [23] [24]

In 2014 F-Droid was chosen as part of the GNU Project's GNU a Day initiative during their 30th anniversary to encourage more use of free software. [25]

In January 2016, Hans-Christoph Steiner, a developer for Calyx Institute, [26] Debian, F-Droid, and Guardian Project, said F-Droid was focusing on issues like security, building with Debian, reproducible builds, software requiring trust of as few people as possible, transparency, user privacy, non-internet distribution of apps, block avoidance, and media distribution. [27]

In March 2016, F-Droid partnered with the Guardian Project and CopperheadOS with the goal of creating "a solution that can be verifiably trusted from the operating system, through the network and network services, all the way up to the app stores and apps themselves". [28] Follow-on project GrapheneOS does not include F-Droid, and is developing their own app distribution method for "higher robustness and security". [29]

On 16 July 2019, the project published a "Public Statement on Neutrality of Free Software". This statement was issued to address the project's failure to prevent "oppression or harassment ... at its communication channels, including its forum", controversy surrounding alt-tech social media website Gab, and to explain how Fediverse client Tusky blocking access to it, while client Fedilab allowed its users to choose, was consistent with their principles. [30] [31] [32] [33] Action was considered against several applications, including Purism's Librem One, to exclude them for allowing access to sites such as Gab or spinster.xyz. [34] [35] [36]

According to Ankush Das writing for ItsFoss.com in 2021, F-Droid is known for hosting open-source apps such as Element or Tusky that have been removed from Google Play store. [37]

Scope of project

The F-Droid website lists the apps hosted, over 3,800; [38] the Google Play Store lists about 3 million apps. [39] The project incorporates several software sub-projects:

- Client software for searching, downloading, verifying, and updating Android apps from an F-Droid repository

- fdroidserver – tool for managing existing repositories and creating new ones

- Jekyll-based website generator for a repository

F-Droid builds apps from publicly available and freely licensed source code. The project says it is run entirely by volunteers and has no formal app review process, [40] but some contributors have been paid for their work. [41] [42] [43] New apps, which must be free of proprietary software, are contributed by user submissions or the developers themselves. [44]

Client application

F-Droid is not available on the Google Play Store. To install the F-Droid client, the user has to allow installation from "Unknown sources" in Android settings [45] and retrieve the F-Droid Android application package (.apk file) from the official site.

The client was designed to be resilient against surveillance, censorship, and unreliable Internet connections. To promote anonymity, it supports HTTP proxies and repositories hosted on Tor onion services. Client devices can function as impromptu "app stores", distributing downloaded apps to other devices over local Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and Android Beam. [46] [47] The F-Droid client app automatically offers updates for installed F-Droid apps; when the F-Droid Privileged Extension is installed, updates can also be installed by the app itself in the background. [48] However, automatic updates are not turned on by default. [49] The extension requires the device to have root access, or to be able to flash a zip file. [50]

Key management

The Android operating system checks that updates are signed with the same key, preventing others from distributing updates that are signed by a different key. [51] [52] Originally, the Google Play store required applications to be signed by the developer of the application, while F-Droid only allowed its own signing keys. So apps previously installed from another source have to be reinstalled to receive updates. [53]

In September 2017 Google Play started offering developers a signing key service managed by Google Play, [54] offering a similar service to what F-Droid offered since 2011, and F-Droid now lets developers use their own keys via the reproducible build process. [55]

Security issues

In 2012, F-Droid announced they had removed an app because of a security flaw that could leak personal information. [56] In 2017, F-Droid stated "No malware has been found in f-droid.org in its 7 years of operation." [57] In 2022, F-Droid discovered over 20 distributed applications contained "known vulnerabilities". [58]

Reception

In August 2019, Rae Hodge of CNET recommended F-Droid as a way to avoid malware from Google apps, which according to Google was a low risk. Advantages of F-Droid were said to include better security odds of open source software, avoidance of tracking in apps and a "stringent security auditing process", no hidden costs, and greater customization. Disadvantages were said to be lack of a rating system, only about 2,600 apps in F-Droid, versus more than 2.5 million in the Play store, and more manual process for updating apps. Editors cautioned F-Droid can give users more control and better privacy and security, but also takes more diligence. [59]

In an April 2022 detailed article for HowtoGeek, Joe Fedewa wrote "The selection of apps is much smaller in F-Droid than the Play Store, around 3,000 compared to around 3 million, but that's to be expected. If you're looking to de-Google your life a bit, or you just want to try some apps that have better ethics, F-Droid is a great place to go." [60]

In a December 2022 detailed article in Popular Science, Justin Pot wrote "F-Droid isn't going to replace Google Play for most people, but it's a nice and simple alternative for finding free and safe apps before you dive into the swamp that is Google's app store." [61]

See also

- Digital distribution

- Kali NetHunter

- List of mobile app distribution platforms

- List of Mobile Device Management software

- Mobile app

- Synaptic (software)

References

- ^ "About". Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "F-Droid Is Here". 29 September 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "CHANGELOG.md · master · F-Droid / Client · GitLab". Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "About". Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "Client 0.54 released". F-droid.org. 5 November 2013. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015.

- ^ Hildenbrand, Jerry (27 November 2012). "F-Droid is the FOSS application store for your Android phone". Android Central. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Nardi, Tom (27 August 2012). "F-Droid: The Android Market That Respects Your Rights". The Powerbase. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ "F-Droid Server Manual". Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Commits by year and month of F-Droid data reported by gitstats". 2017. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "F-Droid initial source code". F-Droid. 19 October 2010. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ a b "F Droid About". Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ F-Droid. "Donations | F-Droid". F-Droid. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Apply for the GitLab Open Source Program (#223) · Issues · F-Droid / admin · GitLab". GitLab. 8 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Interview with Ciaran Gultnieks of F-Droid — Free Software Foundation — Working together for free software". www.fsf.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "F-Droid - Gitorious". 25 December 2010. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "ee/LICENSE · master · GitLab.org / GitLab · GitLab". GitLab. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Martí, Daniel (February 2014). "F-Droid". archive.fosdem.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "FDroid: a free software alternative to Google Market". Replicant Project. 26 November 2010. Archived from the original on 17 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ "FDroid". Replicant Wiki. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "Replicant 6.0 early work, upstream work and F-Droid issue | Replicant". blog.replicant.us. 8 August 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ GNUtoo (3 June 2022). "New Replicant 6.0 0004 release and Replicant 11 status. | Replicant". Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ "Our New F-Droid App Repository". The Guardian Project. 15 March 2012. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Walker-Morgan, Dj (28 February 2012). "FSFE launches "Free Your Android!" campaign". H-online. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "Liberate Your Device!". Free Software Foundation Europe. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "GNU-a-Day". GNU Project. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ "Team - Calyx Institute". calyxinstitute.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Steiner, Hans-Christoph (January 2016). "F-Droid: building the private, unblockable app store". archive.fosdem.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Copperhead, Guardian Project and F-Droid Partner to Build Open, Verifiably Secure Mobile Ecosystem". The Guardian Project. 28 March 2016. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions | GrapheneOS". grapheneos.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Public Statement on Neutrality of Free Software". F-Droid. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Robertson, Adi (12 July 2019). "How the biggest decentralized social network is dealing with its Nazi problem". The Verge. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "TWIF 64: We are back!". F-Droid. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Fedilab (fr.gouv.etalab.mastodon) and FreeTusky (com.thechiefmeat.freetusky) explicitly promote violence (#1736) · Issues · F-Droid / Data". GitLab. 8 August 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "remove spinster app (!6013) · Merge Requests · F-Droid / Data". GitLab. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "depackage Clover (org.floens.chan), Overchan, Overchan (fork), Ouroboros (#1722) · Issues · F-Droid / Data". GitLab. 4 August 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Consider Depackaging Librem One Apps (#1734) · Issues · F-Droid / Data". GitLab. 7 August 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Decentralized Networks Under Attack? Google Removes Open-Source Mastodon Client "Tusky" from the Play Store". It's FOSS News. 18 March 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "F-Droid Main Repository". F-Droid. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Number of available applications in the Google Play Store from December 2009 to December 2020". Statista. 4 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Contribute". F-Droid. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "F-Droid · Expenses - Open Collective". opencollective.com. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Payout request (#194) · Issues · F-Droid / admin". GitLab. 5 January 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Mozilla Speed Dating grant payout and further work (#189) · Issues · F-Droid / admin". GitLab. 5 October 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Inclusion Policy". F-Droid. 4 April 2014. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Android Open Distribution". 31 October 2012. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ "Client 0.76 Released". F-Droid. 14 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ Brandom, Russell (10 June 2014). "Your survival guide for an internet blackout". The Verge. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ "F-Droid Privileged Extension". F-Droid. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Orphanides, K. G. (14 January 2021). "How to move all your WhatsApp groups and get started on Signal". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "org.fdroid.fdroid.privileged.ota_2070". F-Droid. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Marlinspike, Moxie (12 February 2013). "moxie0 commented Feb 12, 2013". Archived from the original on 10 January 2018 – via GitHub.

- ^ "Signing Your Applications". Android Developers. Google. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "Release Channels and Signing Keys". F-Droid. 12 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Glick, Kobi (6 September 2017). "Enroll for app signing in the Google Play Console & secure your app using Google's robust security infrastructure". Android Developers Blog. Google. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "Reproducible Builds". F-Droid. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ F-Droid (23 August 2012). "Security Notice – TextSecure". F-Droid.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ F-Droid (13 December 2017). "F-Droid and the Janus Vulnerability". F-Droid.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Flag many apps with KnownVuln (!11496) · Merge requests · F-Droid / Data · GitLab". GitLab. August 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Hodge, Ron (6 August 2019). "Fight Android malware by quitting Google Play and using F-Droid for Android apps". CNET. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ Fedewa, Joe (18 April 2022). "What Is F-Droid and How Is It Different From the Play Store?". How-To Geek. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ "How to set up F-Droid, the open-source alternative to the Google Play Store". Popular Science. 24 December 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

Further reading

- Amadeo, Ron (29 July 2014). "The great Ars experiment—free and open source software on a smartphone?!". Ars Technica. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- Lemmer-Webber, Morgan; Lemmer-Webber, Christine (14 May 2023). "57: F-Droid (featuring Sylvia van Os & Hans-Christoph Steiner!)". fossandcrafts.org. FOSS and Crafts. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

External links

| |

Screenshot of F-Droid 1.19.0 on Android showing the latest apps | |

| Developer(s) | Ciaran Gultnieks

[1]

|

|---|---|

| Initial release | 29 September 2010

[2]

|

| Stable release | 1.17.0

[3]

|

| Repository | |

| Written in | Python (server tools), Jekyll (software) (site), Java (client) |

| Operating system | Android (client), Linux, macOS, Windows 10, FreeBSD (server) |

| Type | Digital distribution of free software, Software repository |

| License | GNU Affero General Public License, version 3.0 or later

[4]

|

| Website |

f-droid |

F-Droid is an open-source app store and software repository for Android, serving a similar function to the Google Play store. The main repository, hosted by the project, contains only free and open source apps. Applications can be browsed, downloaded and installed from the F-Droid website or client app without the need to register for an account. "Anti-features" such as advertising, user tracking, or dependence on non-free software are flagged in app descriptions. [5]

The website also offers the source code of applications it hosts, as well as the software running the F-Droid server, allowing anyone to set up their own app repository. [6] [7] [8]

History

F-Droid was founded by Ciaran Gultnieks in 2010. The client was forked from Aptoide's source code. [10] [11] The project was initially run by the English nonprofit F-Droid Limited. [11] As of 2021, F-Droid Limited was no longer used for donations, [12] and was being shut down, according to spokesman Hans-Cristoph Steiner. [13]

In a 2014 interview for Free Software Foundation, Gultnieks said he was inspired to launch F-Droid because of "lock-down, lock-in and general nefarious behavior from software" on phones. [14]

From 2010 to 2015, F-Droid used the AGPL-licensed Gitorious repository system for development. [15] In 2015, it transitioned to proprietary licensed GitLab [16] when Gitorious was acquired by GitLab. According to Daniel Marti, Former F-Droid Developer, in 2013, removal of AdAway from the Google Play Store caused a spike in searches and downloads of F-Droid, and he estimated there were 30 to 40 thousand users. [17]

Replicant, a fully free software Android operating system, previously used F-Droid as its default and recommended app store. [18] [19] In 2016, the Replicant project determined F-Droid did not comply with GNU Free System Distribution Guidelines, and asked for assistance correcting it, but progress stalled. [20] In June 2022, Replicant announced they had removed F-Droid. [21]

Guardian Project, a suite of free and secure Android applications, started running their own F-Droid repository in early 2012. [22] In 2012, Free Software Foundation Europe featured F-Droid in their Free Your Android! campaign to raise awareness of the privacy and security risks of proprietary software. [23] [24]

In 2014 F-Droid was chosen as part of the GNU Project's GNU a Day initiative during their 30th anniversary to encourage more use of free software. [25]

In January 2016, Hans-Christoph Steiner, a developer for Calyx Institute, [26] Debian, F-Droid, and Guardian Project, said F-Droid was focusing on issues like security, building with Debian, reproducible builds, software requiring trust of as few people as possible, transparency, user privacy, non-internet distribution of apps, block avoidance, and media distribution. [27]

In March 2016, F-Droid partnered with the Guardian Project and CopperheadOS with the goal of creating "a solution that can be verifiably trusted from the operating system, through the network and network services, all the way up to the app stores and apps themselves". [28] Follow-on project GrapheneOS does not include F-Droid, and is developing their own app distribution method for "higher robustness and security". [29]

On 16 July 2019, the project published a "Public Statement on Neutrality of Free Software". This statement was issued to address the project's failure to prevent "oppression or harassment ... at its communication channels, including its forum", controversy surrounding alt-tech social media website Gab, and to explain how Fediverse client Tusky blocking access to it, while client Fedilab allowed its users to choose, was consistent with their principles. [30] [31] [32] [33] Action was considered against several applications, including Purism's Librem One, to exclude them for allowing access to sites such as Gab or spinster.xyz. [34] [35] [36]

According to Ankush Das writing for ItsFoss.com in 2021, F-Droid is known for hosting open-source apps such as Element or Tusky that have been removed from Google Play store. [37]

Scope of project

The F-Droid website lists the apps hosted, over 3,800; [38] the Google Play Store lists about 3 million apps. [39] The project incorporates several software sub-projects:

- Client software for searching, downloading, verifying, and updating Android apps from an F-Droid repository

- fdroidserver – tool for managing existing repositories and creating new ones

- Jekyll-based website generator for a repository

F-Droid builds apps from publicly available and freely licensed source code. The project says it is run entirely by volunteers and has no formal app review process, [40] but some contributors have been paid for their work. [41] [42] [43] New apps, which must be free of proprietary software, are contributed by user submissions or the developers themselves. [44]

Client application

F-Droid is not available on the Google Play Store. To install the F-Droid client, the user has to allow installation from "Unknown sources" in Android settings [45] and retrieve the F-Droid Android application package (.apk file) from the official site.

The client was designed to be resilient against surveillance, censorship, and unreliable Internet connections. To promote anonymity, it supports HTTP proxies and repositories hosted on Tor onion services. Client devices can function as impromptu "app stores", distributing downloaded apps to other devices over local Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and Android Beam. [46] [47] The F-Droid client app automatically offers updates for installed F-Droid apps; when the F-Droid Privileged Extension is installed, updates can also be installed by the app itself in the background. [48] However, automatic updates are not turned on by default. [49] The extension requires the device to have root access, or to be able to flash a zip file. [50]

Key management

The Android operating system checks that updates are signed with the same key, preventing others from distributing updates that are signed by a different key. [51] [52] Originally, the Google Play store required applications to be signed by the developer of the application, while F-Droid only allowed its own signing keys. So apps previously installed from another source have to be reinstalled to receive updates. [53]

In September 2017 Google Play started offering developers a signing key service managed by Google Play, [54] offering a similar service to what F-Droid offered since 2011, and F-Droid now lets developers use their own keys via the reproducible build process. [55]

Security issues

In 2012, F-Droid announced they had removed an app because of a security flaw that could leak personal information. [56] In 2017, F-Droid stated "No malware has been found in f-droid.org in its 7 years of operation." [57] In 2022, F-Droid discovered over 20 distributed applications contained "known vulnerabilities". [58]

Reception

In August 2019, Rae Hodge of CNET recommended F-Droid as a way to avoid malware from Google apps, which according to Google was a low risk. Advantages of F-Droid were said to include better security odds of open source software, avoidance of tracking in apps and a "stringent security auditing process", no hidden costs, and greater customization. Disadvantages were said to be lack of a rating system, only about 2,600 apps in F-Droid, versus more than 2.5 million in the Play store, and more manual process for updating apps. Editors cautioned F-Droid can give users more control and better privacy and security, but also takes more diligence. [59]

In an April 2022 detailed article for HowtoGeek, Joe Fedewa wrote "The selection of apps is much smaller in F-Droid than the Play Store, around 3,000 compared to around 3 million, but that's to be expected. If you're looking to de-Google your life a bit, or you just want to try some apps that have better ethics, F-Droid is a great place to go." [60]

In a December 2022 detailed article in Popular Science, Justin Pot wrote "F-Droid isn't going to replace Google Play for most people, but it's a nice and simple alternative for finding free and safe apps before you dive into the swamp that is Google's app store." [61]

See also

- Digital distribution

- Kali NetHunter

- List of mobile app distribution platforms

- List of Mobile Device Management software

- Mobile app

- Synaptic (software)

References

- ^ "About". Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "F-Droid Is Here". 29 September 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "CHANGELOG.md · master · F-Droid / Client · GitLab". Retrieved 7 August 2023.

- ^ "About". Retrieved 29 September 2020.

- ^ "Client 0.54 released". F-droid.org. 5 November 2013. Archived from the original on 26 April 2015.

- ^ Hildenbrand, Jerry (27 November 2012). "F-Droid is the FOSS application store for your Android phone". Android Central. Archived from the original on 16 June 2018. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Nardi, Tom (27 August 2012). "F-Droid: The Android Market That Respects Your Rights". The Powerbase. Archived from the original on 3 December 2013. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ "F-Droid Server Manual". Archived from the original on 6 November 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ^ "Commits by year and month of F-Droid data reported by gitstats". 2017. Archived from the original on 9 July 2017. Retrieved 19 July 2017.

- ^ "F-Droid initial source code". F-Droid. 19 October 2010. Archived from the original on 10 December 2014. Retrieved 10 December 2014.

- ^ a b "F Droid About". Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 28 January 2014.

- ^ F-Droid. "Donations | F-Droid". F-Droid. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Apply for the GitLab Open Source Program (#223) · Issues · F-Droid / admin · GitLab". GitLab. 8 May 2021. Retrieved 10 May 2022.

- ^ "Interview with Ciaran Gultnieks of F-Droid — Free Software Foundation — Working together for free software". www.fsf.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "F-Droid - Gitorious". 25 December 2010. Archived from the original on 25 December 2010. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "ee/LICENSE · master · GitLab.org / GitLab · GitLab". GitLab. Retrieved 11 May 2022.

- ^ Martí, Daniel (February 2014). "F-Droid". archive.fosdem.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "FDroid: a free software alternative to Google Market". Replicant Project. 26 November 2010. Archived from the original on 17 January 2015. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- ^ "FDroid". Replicant Wiki. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018. Retrieved 8 March 2018.

- ^ "Replicant 6.0 early work, upstream work and F-Droid issue | Replicant". blog.replicant.us. 8 August 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ GNUtoo (3 June 2022). "New Replicant 6.0 0004 release and Replicant 11 status. | Replicant". Retrieved 3 August 2022.

- ^ "Our New F-Droid App Repository". The Guardian Project. 15 March 2012. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 29 August 2013.

- ^ Walker-Morgan, Dj (28 February 2012). "FSFE launches "Free Your Android!" campaign". H-online. Archived from the original on 23 July 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "Liberate Your Device!". Free Software Foundation Europe. Archived from the original on 15 August 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- ^ "GNU-a-Day". GNU Project. Archived from the original on 28 July 2014. Retrieved 23 July 2014.

- ^ "Team - Calyx Institute". calyxinstitute.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ Steiner, Hans-Christoph (January 2016). "F-Droid: building the private, unblockable app store". archive.fosdem.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Copperhead, Guardian Project and F-Droid Partner to Build Open, Verifiably Secure Mobile Ecosystem". The Guardian Project. 28 March 2016. Archived from the original on 20 April 2016. Retrieved 19 April 2016.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions | GrapheneOS". grapheneos.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Public Statement on Neutrality of Free Software". F-Droid. Retrieved 3 August 2020.

- ^ Robertson, Adi (12 July 2019). "How the biggest decentralized social network is dealing with its Nazi problem". The Verge. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "TWIF 64: We are back!". F-Droid. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Fedilab (fr.gouv.etalab.mastodon) and FreeTusky (com.thechiefmeat.freetusky) explicitly promote violence (#1736) · Issues · F-Droid / Data". GitLab. 8 August 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "remove spinster app (!6013) · Merge Requests · F-Droid / Data". GitLab. 3 December 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "depackage Clover (org.floens.chan), Overchan, Overchan (fork), Ouroboros (#1722) · Issues · F-Droid / Data". GitLab. 4 August 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Consider Depackaging Librem One Apps (#1734) · Issues · F-Droid / Data". GitLab. 7 August 2019. Retrieved 8 February 2021.

- ^ "Decentralized Networks Under Attack? Google Removes Open-Source Mastodon Client "Tusky" from the Play Store". It's FOSS News. 18 March 2021. Retrieved 22 April 2022.

- ^ "F-Droid Main Repository". F-Droid. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Number of available applications in the Google Play Store from December 2009 to December 2020". Statista. 4 February 2021. Retrieved 7 February 2021.

- ^ "Contribute". F-Droid. Archived from the original on 18 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "F-Droid · Expenses - Open Collective". opencollective.com. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Payout request (#194) · Issues · F-Droid / admin". GitLab. 5 January 2021. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Mozilla Speed Dating grant payout and further work (#189) · Issues · F-Droid / admin". GitLab. 5 October 2020. Retrieved 9 February 2021.

- ^ "Inclusion Policy". F-Droid. 4 April 2014. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ "Android Open Distribution". 31 October 2012. Archived from the original on 24 March 2018. Retrieved 31 October 2012.

- ^ "Client 0.76 Released". F-Droid. 14 October 2014. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- ^ Brandom, Russell (10 June 2014). "Your survival guide for an internet blackout". The Verge. Archived from the original on 8 August 2014. Retrieved 2 August 2014.

- ^ "F-Droid Privileged Extension". F-Droid. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Orphanides, K. G. (14 January 2021). "How to move all your WhatsApp groups and get started on Signal". Wired UK. ISSN 1357-0978. Retrieved 10 February 2021.

- ^ "org.fdroid.fdroid.privileged.ota_2070". F-Droid. Archived from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- ^ Marlinspike, Moxie (12 February 2013). "moxie0 commented Feb 12, 2013". Archived from the original on 10 January 2018 – via GitHub.

- ^ "Signing Your Applications". Android Developers. Google. Archived from the original on 15 April 2016. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "Release Channels and Signing Keys". F-Droid. 12 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- ^ Glick, Kobi (6 September 2017). "Enroll for app signing in the Google Play Console & secure your app using Google's robust security infrastructure". Android Developers Blog. Google. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 16 April 2016.

- ^ "Reproducible Builds". F-Droid. Archived from the original on 11 July 2018. Retrieved 10 July 2018.

- ^ F-Droid (23 August 2012). "Security Notice – TextSecure". F-Droid.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ F-Droid (13 December 2017). "F-Droid and the Janus Vulnerability". F-Droid.org. Retrieved 21 April 2022.

- ^ "Flag many apps with KnownVuln (!11496) · Merge requests · F-Droid / Data · GitLab". GitLab. August 2022. Retrieved 6 December 2022.

- ^ Hodge, Ron (6 August 2019). "Fight Android malware by quitting Google Play and using F-Droid for Android apps". CNET. Retrieved 3 June 2023.

- ^ Fedewa, Joe (18 April 2022). "What Is F-Droid and How Is It Different From the Play Store?". How-To Geek. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- ^ "How to set up F-Droid, the open-source alternative to the Google Play Store". Popular Science. 24 December 2022. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

Further reading

- Amadeo, Ron (29 July 2014). "The great Ars experiment—free and open source software on a smartphone?!". Ars Technica. Retrieved 29 July 2014.

- Lemmer-Webber, Morgan; Lemmer-Webber, Christine (14 May 2023). "57: F-Droid (featuring Sylvia van Os & Hans-Christoph Steiner!)". fossandcrafts.org. FOSS and Crafts. Retrieved 3 June 2023.