Bethel A. M. E. Church | |

| |

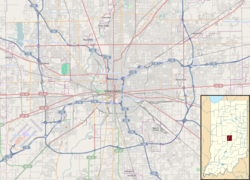

| Location | 414 W. Vermont St., Indianapolis, Indiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°46′23″N 86°9′56″W / 39.77306°N 86.16556°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1869 |

| Architect | Adam Busch |

| Architectural style | Modern Movement, Romanesque, Post Modern |

| NRHP reference No. | 91000269 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | March 21, 1991 |

The Bethel A.M.E. Church, known in its early years as Indianapolis Station or the Vermont Street Church, is a historic African Methodist Episcopal Church in Indianapolis, Indiana. Organized in 1836, it is the city's oldest African-American congregation. The three-story church on West Vermont Street dates to 1869 and was added to the National Register in 1991. The surrounding neighborhood, once the heart of downtown Indianapolis's African American community, significantly changed with post- World War II urban development that included new hotels, apartments, office space, museums, and the Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis campus. In 2016 the congregation sold their deteriorating church, which will be used in a future commercial development. The congregation built a new worship center at 6417 Zionsville Road in Pike Township in northwest Indianapolis.

The Bethel AME congregation has a long history of supporting the city's African American community. It is especially noted for its activities on behalf of the antislavery movement in the years before the American Civil War; its support of the Underground Railroad, which provided protection to slaves en route to Canada; and its commitment to education and community outreach. Bethel also served as the mother church to several AME congregations in Indiana and as a public meeting place in Indianapolis for social activists. Local chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Indiana State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs were organized at the Vermont Street church in the early 1900s.

History

Indianapolis became home to several African Methodist Episcopal Church congregations, but Bethel is the city's oldest African American congregation. Originally established in 1836 and known as Indianapolis Station, it had adopted the name of Bethel AME Church by 1869. [2]

Origins

Augustus Turner, a local barber, organized a small group of African American Methodists in 1836. The congregation's first meetings were held in Turner's log cabin on Georgia Street. A new house of worship was constructed on Georgia Street in 1841. When the congregation sought affiliation with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, William Paul Quinn, an AME circuit rider from Cincinnati, Ohio, who later became an AME bishop, was the first AME minister to serve the Indianapolis Station. Quinn also helped it achieve membership in the AME Church's Western Circuit. Elisha Weaver began serving as the church's first full-time minister in 1850. The congregation adopted the name of Bethel AME Church in the late 1860s. [2] [3] Although the congregation continued to expand into larger buildings and extend its outreach programs to the area's African American community, it faced financial challenges throughout its early history. [4]

Georgia Street church

In 1841 the congregation had its first church built on Georgia Street between the Central Canal and Mississippi Street (present-day Senate Avenue). [5] The Bethel AME congregation continued to use the small, frame structure until 1857, when it bought the first Christ Church building from the city's Episcopal congregation. (The Episcopal parishioners had decided to replace their wood-frame church with a new stone structure on its site on Monument Circle.) The AME congregation had the small church moved to their site on Georgia Street; however, the church was destroyed by fire in 1862. [6] [7] It is believed that the AME congregation's open support of the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad, which provided protection to slaves en route to Canada, may have led some pro-slavery advocates to burn the church. [3] The congregation raised funds and had the frame church rebuilt in 1867. The replacement structure served the congregation until its brick church on West Vermont Street was built in 1868–69. [5] The congregation sold a lot it owned at the corner of Michigan and Tennessee Streets (present-day Capitol Avenue) for $3,000 and used the funds to purchase another lot for $5,000 on West Vermont Street that served as the site for the new church. [1]

Vermont Street church

The church's West Vermont Street site, located in the northwest section of downtown Indianapolis, has historically been the heart of the African American community. The neighborhood included a mix of residential, retail, commercial, and light industry. [1] [2] In 1867 the congregation contracted with Adam Busch to build a new brick church on its West Vermont Street lot. The church was supposed to have cost $10,400. By 1869, when the building was only partially completed, the congregation moved into the new church at 414 West Vermont Street and adopted the name of Bethel AME Church. [5] [8] Bethel congregation sold or mortgaged other property it owned to complete construction of the church. The church was sold on July 24, 1880, to pay off its debts, but its new owner allowed the congregation to repurchase the property in 1891 when sufficient funds had been raised to pay off a mortgage. Subsequent mortgages on the church were paid off in 1944, 1961, and 1982. [9]

Post- World War II development and the declining nearby neighborhood caused the area to change, but the Bethel AME congregation remained in its aging church, which was renovated in 1974 in order to make more space for outreach activities. Eventually, urban development dominated the surrounding area, which included hotels, apartments, museums, and office space along the Central Canal to the east, north, and south. The sprawling IUPUI campus was established west of the church. [1] [2]

Bethel AME Church was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1991; at that time it was the only African-American church building in Indianapolis to receive that recognition. [2] The state historical marker for Bethel AME Church, which is located across from the building on West Vermont Street, was dedicated on June 20, 2009, to commemorate the site that Indianapolis's oldest African-American church had occupied since 1869. [10] [11]

Sale and future development

In 2015 the Bethel AME congregation initiated a capital campaign to raise the $2 million to $3 million needed to repair the deteriorating building, but it proved to be unsuccessful. Without the major funding needed to proceed with the church repairs, the congregation began considering offers to buy the Vermont Street property. In early 2016 the congregation reached an agreement with SUN Development and Management Corporation, an Indianapolis-based developer, to sell the property for an undisclosed amount and relocate. SUN Development, who agreed to preserve as much of the structure as possible, planned to build a hotel on the property. Under the terms of the sale, the congregation had to vacate the property by August 2016. [12] [13]

In February 2017 Indiana University announced that its School of Informatics and Computing at IUPUI had received a grant from the university to create a three-dimensional virtual reality model of the historic Vermont Street church. IUPUI students collected 3,000 images for use in the modeling project. When completed, the model will be accessible to the public through IUPUI's School of Informatics and Computing. Digital images used to create the model will be housed at the IUPUI Library; the digitized archive, along with other archival records from the church, will be held in collection of the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis. [14]

In 2018, the congregation' opened a new church building on Zionsville Road in Pike Township in northwest Indianapolis. [15]

Building description

The Vermont Street site originally consisted of a three-story church and an adjacent two-story parsonage that connected to the main building by an enclosed passageway. The church and parsonage date from 1867 to 1869; the parsonage was converted to a church office at a later date. The church's four-story tower, east gable, and west cross gable were added as part of a major renovation to the church in 1894. A false façade of metal framework and stucco was added to the church's and parsonage's south façade in 1973–74. The church's original brick façade and its main entrance was partially obscured by the 1974 update; however, the building retained many features dating to its construction in 1869 and the renovation in 1894. [1] [16]

Exterior and plan

The three-story church and its square, four-story tower were constructed of red brick over a limestone foundation and contained some Romanesque Revival features. [16] Only the northeast corner of the tower was attached to the church. The tower had paired windows on the second story, multiple round arches above the third-floor windows, and a round arch flanked by pairs of pilasters at the fourth-story level. The tower's hip roof was topped with a cross finial. [1]

The church's main entrance, facing south toward Vermont Street, had a false façade of stucco that included a single arch over the main entrance and two narrow arches on either side. [16] [17] The church's east elevation, partially obscured by the adjacent parsonage, had a cross-gabled section with tall, round-arched windows and two-story arched windows that divided into two lancets at the second-story level. The church's west elevation had vertically-aligned window openings and one doorway on the south. (Another door on the north of this elevation was enclosed.) The west elevation's second and third stories each had five, round-arched windows; its cross gable had a lunette window. The north (rear) elevation had a gabled section with two arched windows on the first story, one round-arched window on the second story, and two round-arched windows on the third floor. A hip-roofed section at the rear had an arched doorway and a window on the ground floor with a two-story arched window that divided into two round-arched lancet windows above. The rear elevation also had an exterior chimney. [1]

An adjacent, two-story parsonage east of the church was erected at the time of the church's initial construction (1867–69). The red brick parsonage connected to the church on the first and second floor and was later converted to a church office. Its gable front (the main façade facing Vermont Street) was covered with a false façade in 1974. Openings in the south façade were blocked in, probably when the false façade was added. A gable-roof porch covered the parsonage's main entry. Originally, the south elevation had arched openings with a door and two windows on the first floor and three windows on the second floor. The east elevation had a two-story gabled main section and a shed-roofed section in the rear. The main section had two windows on the first floor, one on the second; the shed-roof section had one window. [1]

Interior

The church's cube-shaped interior included a sanctuary and meeting rooms; its tower housed a staircase. The church had two entrances, one on its south elevation facing Vermont Street and another in the tower. A narrow lobby across the main building had doors in the north side that lead to a meeting room. Smaller rooms were established along the west wall. The lower level included a kitchen. The main stairway to the second-floor sanctuary was accessed from the east side of the first-floor lobby. [1]

The sanctuary was remodeled in 1894 to a two-story space with the altar on the east wall. A balcony along the west wall was accessible from staircases in the sanctuary's southeast and northwest corners. Auditorium-style seating faced the altar. (This arrangement altered the original plan, which may have placed rows of pews facing an altar located on either the north or south wall.) Two tiers of windows on the west and north walls lighted the sanctuary; tall windows lit the altar. The coved ceiling was covered with beaded wood board and had a square coffer at the center. [1]

Later changes to the building included enlarging its choir loft, installation of a pipe organ and stained-glass windows, and updates to the building's heating, lighting, and electrical systems. [16] [9] The church's hand-carved pulpit was a gift from Reverend Andre Chambers in honor of his wife, Lettie. [18] In 1961 pastor C. T. H. Watkins and architect Walter Exxell redesigned the church's chancel. [18] The congregation also renovated the church building and adjoining parsonage in 1974. [2] Window openings in the sanctuary's south wall were covered over and the related woodwork was removed due to the addition of the false façade on the exterior. [1]

The front door of the parsonage/church office led to a side staircase and hall. A first-floor room was converted to an office. In addition, smaller rooms or offices were made on the parsonage's first and second floors. [1]

Mission

The Bethel AME Church elevated its role in the community as the city's black population increased. [2] [4] Indianapolis's African American population was small during the early decades of the nineteenth century. In 1840, shortly after the congregation organized, only 195 blacks lived in the city. [19] Before the American Civil War, the congregation became active in the antislavery movement and supported the Underground Railroad. [3] At that time Indianapolis's black population comprised less than three percent of the city's total population. In 1860, when Indiana's statewide population reached 1,338,710, its African American population was 11,428. However, as the war progressed, the number of blacks coming to Indianapolis from the South and Indiana's rural areas continued to rise, nearly doubling the state's African American population by 1870, a few years after the Bethel AME church was erected on Vermont Street. By 1900, shortly after the church underwent a major renovation, African Americans comprised nearly ten percent of the city's population. [5] [19] [20]

Bethel, the city's only AME congregation for thirty years, became the mother church to several congregations of the African Methodist Episcopal churches in Indiana, [3] including the Allen Chapel, Coppin Chapel, Saint John, and Wallace (Providence) congregations. [21] The Bethel congregation also served in the development of the AME church. In 1854, 1859, and 1864, Bethel hosted the denomination's annual conference. [2] [22] In addition, it hosted an AME bishop's conference and a general conference in 1888. [9]

Education was also an important mission of the church. The congregation established its first school for African American children at the church in 1858. (Before the mid-1870s, Indianapolis's public schools did not allow African American children to enroll.) Later, the congregation operated a kindergarten at the church and a day school. [3] [5]

The Bethel church also became a public meeting place for social activism, as well as a venue for organizing and implementing social services including providing money, clothing, and temporary lodging to African Americans immigrating to the city from the South after the Civil War. [23] Over the years the church provided other social programs such as a credit union, counseling services, a well-baby clinic, and day-care services for children and adults. [21] The church also served as a venue for organizing local associations that were instrumental in achieving better housing, education, and equal rights for African Americans. Local chapters of several organizations were created at Bethel, including the Indianapolis chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in the early 1900s and the Indiana State Federation of Colored Woman's Clubs on April 27, 1904. [3] [11] [24]

During the twentieth century, Bethel AME Church continued to support the city's black community living northwest of the downtown area. The congregation operated a food pantry, youth and senior citizens programs, and clothing drives, among other activities. [1] Throughout civil rights activism of the mid-twentieth century, Bethel provided a space of racial solidarity and continued its long tradition of offering community outreach services to the city's African Americans. [2] [25] In 2013 the church became a member of the Indianapolis Congregation Action Network (IndyCan) and has served as headquarters for the network's Mass Transit Campaign. [26]

Membership

The congregation began in 1836 with a few members meeting in a log cabin. By 1848 the small group had grown to 100 members and was meeting in a small frame church on Georgia Street. [3] In the early 1860s, before the congregation expanded to the large brick church on West Vermont Street, the church's membership reached 120. [27] Over the next century the membership continued to increase. By the early 1990s the congregation had an estimated 1,200 members; [2] however, its membership declined in subsequent decades. The congregation's membership was estimated at 120 to 150 when the West Vermont Street property was sold in 2016. [12] [13]

Notable members

- Reverend Willis Revels, a pastor at Bethel AME Church in the 1860s, encouraged African Americans to enlist in the Union army during the American Civil War [27] [28]

- Doctor Samuel Elbert, a physician, was the first African American graduate of the Medical College of Indianapolis and served as the secretary of the Indiana Board of Health [5]

- Madam C. J. Walker, a prominent African American hair care and beauty products entrepreneur, who was also philanthropist and activist in the early twentieth century [5]

- Doctor Joseph Ward, an Indianapolis physician, served as director of the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Medical Center at Tuskegee, Alabama [5]

- Mercer Mance was Indiana's first elected African American judge [5]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Michelle D. Hale, "Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church," in David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, ed. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 318–19. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Aboard the Underground Railroad, Bethel A.M.E. Church". National Park Service. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ a b Stanley Warren (Summer 2007). "The Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 19 (3). Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Society: 32. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i The History of Nine Urban Churches. Indianapolis, IN: The Riley-Lockerbie Ministerial Association of Downtown Indianapolis.

- ^ Most secondary sources report that the fire destroyed the AME congregation's Georgia Street church in 1862; however, Warren, p. 33, says it occurred in July 1864.

- ^ The Christ Church building that the Bethel AME congregation purchased in 1857 was constructed on the Circle in 1838. The Gothic Revival-style structure was painted white and measured 29 feet (8.8 m) by 43 feet (13 m). It had a total seating capacity of 350 people. See Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 413. See also: Carl R. Stockton (1987). Christ Church in Indianapolis: A Selected Chronology. Indianapolis, Indiana: C. R. Stockton. pp. 3–5. See also: Eli Lilly (1957). History of the Little Church on the Circle: Christ Church Parish, Indianapolis, 1837–1955. Indianapolis, Indianapolis: Rector Wardens and Vestrymen of Christ Protestant Episcopal Church. pp. 52–54, 127.

- ^ "Forged Through Fire: Bethel AME Church, Indianapolis Station AME Church, 1836-1869". Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c Warren, pp. 34–35.

- ^ "June 20, 2009–Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ a b "Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Kelly Patrick Slone (April 21, 2016). "Historic Bethel AME Church Sold for Hotel Project". Indianapolis Recorder. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ a b Olivia Lewis (August 22, 2015). "Bethel AME Fights to Keep Legacy Alive". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017. See also: Olivia Lewis (April 11, 2016). "Indy's Oldest African-American Church sold for Hotel Space". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "IUPUI Newsroom: IUPUI Faculty Use Grant to Help Digitally Preserve Historic Indianapolis African-American Church". Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. February 15, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "Church History". Bethel Cathedral AME Church. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Bethel AME Church, Indianapolis (Marion County)" (PDF). Travels in Time: African American Sites. Indiana Department of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ The church's original south façade, now covered, had three openings on its upper and lower portions. The main entrance had a large, round arch. A gabled dormer with a large, round arched window was centered above the entry; however, it was removed as part of the 1973 alteration to the south façade. See "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b The Art and Architecture of Nine Urban Churches. Indianapolis, Indiana: The Riley-Lockerbie Ministerial Association of Downtown Indianapolis.

- ^ a b M. Teresa Baer (2012). Indianapolis: A City of Immigrants. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-87195-299-8.

- ^ Emma Lou Thornbrough, "African-Americans," in David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, ed. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 5–14.

- ^ a b Warren, pp. 33, 35.

- ^ Warren, pp. 32, 33, 34.

- ^ "Colored Immigrants in Indiana: Their Character and Location". The Indianapolis Leader: 1–2. January 24, 1880. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ "Above the Underground Railroad: Bethel AME Church". National Park Service. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Bethel A.M.E. Church, Indianapolis, Indiana. Interviews by Melissa Burlock, 18–21 July 2013. Audio recordings, IUPUI Special Collections and Archives, e-Archives, https://archives.iupui.edu/handle/2450/6956/browse?type=dateissued.

-

^ Carey A. Grady, Senior Pastor of Bethel A.M.E. Church. Phone conversation with writer, 14 July 2014. See also:

"IndyCAN heralds mass transit bill passage". NUVO. Indianapoliis, Indiana. Retrieved July 14, 2014. See also:

"Archived copy". Archived from

the original on 2014-07-18. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

{{ cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title ( link) - ^ a b Warren, p. 33.

- ^ Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 1191.

References

- "Aboard the Underground Railroad, Bethel A.M.E. Church". National Park Service. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- The Art and Architecture of Nine Urban Churches. Indianapolis, Indiana: The Riley-Lockerbie Ministerial Association of Downtown Indianapolis.

- Baer, M. Teresa (2012). Indianapolis: A City of Immigrants. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-87195-299-8.

- "Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- "Bethel A.M.E. Church, Indianapolis, Indiana: Interviews by Melissa Burlock, July 18–21, 2013" (audio recording). IUPUI Special Collections and Archives, e-Archives.

- "Bethel AME Church, Indianapolis (Marion County)" (PDF). Travels in Time: African American Sites. Indiana Department of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

-

"Bethel Cathedral (Archived copy)". Archived from

the original on July 18, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.* Bodenhamer, David J., and Robert G. Barrows, eds. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

ISBN

0-253-31222-1.

{{ cite book}}:|author=has generic name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - "Colored Immigrants in Indiana: Their Character and Location". The Indianapolis Leader. Indianapolis, Indiana: 1–2. January 24, 1880. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- "Forged Through Fire: Bethel AME Church, Indianapolis Station AME Church, 1836-1869". Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- The History of Nine Urban Churches. Indianapolis, IN: The Riley-Lockerbie Ministerial Association of Downtown Indianapolis.

- "IndyCAN heralds mass transit bill passage". NUVO. Indianapoliis, Indiana. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- "IUPUI Newsroom: IUPUI Faculty Use Grant to Help Digitally Preserve Historic Indianapolis African-American Church". Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. February 15, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- "June 20, 2009 –Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Indiana Historical Bureau. June 20, 2009. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- Lewis, Olivia (August 22, 2015). "Bethel AME Fights to Keep Legacy Alive". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Lewis, Olivia (April 11, 2016). "Indy's Oldest African-American Church sold for Hotel Space". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Lilly, Eli (1957). History of the Little Church on the Circle: Christ Church Parish, Indianapolis, 1837–1955. Indianapolis, Indianapolis: Rector Wardens and Vestrymen of Christ Protestant Episcopal Church.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Slone, Kelly Patrick (April 21, 2016). "Historic Bethel AME Church Sold for Hotel Project". Indianapolis Recorder. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Stockton, Carl R. (1987). Christ Church in Indianapolis: A Selected Chronology. Indianapolis, Indiana: C. R. Stockton.

- Warren, Stanley (Summer 2007). "The Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 19 (3). Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Society: 32. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- "Welcome to Bethel AME Church". Bethel AME Church. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

External links

- Bethel AME Church Timeline

- "Bethel A.M.E. Church Records, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1922–2015" Collection Guide, Indiana Historical Society

- "Bethel A.M.E. Church Addition 1871–2016" Collection Guide, Indiana Historical Society

- "Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (Indpls.) Board Minutes, 1871–1909" Collection Guide, Indiana Historical Society

- "Bethel A.M.E. Church (Indianapolis, Ind.) Sunday School Records" Collection Guide, Indiana Historical Society

- African-American history of Indianapolis

- African Methodist Episcopal churches in Indiana

- Churches on the National Register of Historic Places in Indiana

- Romanesque Revival church buildings in Indiana

- Churches completed in 1869

- Churches in Indianapolis

- 1869 establishments in Indiana

- National Register of Historic Places in Indianapolis

Bethel A. M. E. Church | |

| |

| Location | 414 W. Vermont St., Indianapolis, Indiana |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 39°46′23″N 86°9′56″W / 39.77306°N 86.16556°W |

| Area | less than one acre |

| Built | 1869 |

| Architect | Adam Busch |

| Architectural style | Modern Movement, Romanesque, Post Modern |

| NRHP reference No. | 91000269 [1] |

| Added to NRHP | March 21, 1991 |

The Bethel A.M.E. Church, known in its early years as Indianapolis Station or the Vermont Street Church, is a historic African Methodist Episcopal Church in Indianapolis, Indiana. Organized in 1836, it is the city's oldest African-American congregation. The three-story church on West Vermont Street dates to 1869 and was added to the National Register in 1991. The surrounding neighborhood, once the heart of downtown Indianapolis's African American community, significantly changed with post- World War II urban development that included new hotels, apartments, office space, museums, and the Indiana University–Purdue University at Indianapolis campus. In 2016 the congregation sold their deteriorating church, which will be used in a future commercial development. The congregation built a new worship center at 6417 Zionsville Road in Pike Township in northwest Indianapolis.

The Bethel AME congregation has a long history of supporting the city's African American community. It is especially noted for its activities on behalf of the antislavery movement in the years before the American Civil War; its support of the Underground Railroad, which provided protection to slaves en route to Canada; and its commitment to education and community outreach. Bethel also served as the mother church to several AME congregations in Indiana and as a public meeting place in Indianapolis for social activists. Local chapters of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People and the Indiana State Federation of Colored Women's Clubs were organized at the Vermont Street church in the early 1900s.

History

Indianapolis became home to several African Methodist Episcopal Church congregations, but Bethel is the city's oldest African American congregation. Originally established in 1836 and known as Indianapolis Station, it had adopted the name of Bethel AME Church by 1869. [2]

Origins

Augustus Turner, a local barber, organized a small group of African American Methodists in 1836. The congregation's first meetings were held in Turner's log cabin on Georgia Street. A new house of worship was constructed on Georgia Street in 1841. When the congregation sought affiliation with the African Methodist Episcopal Church, William Paul Quinn, an AME circuit rider from Cincinnati, Ohio, who later became an AME bishop, was the first AME minister to serve the Indianapolis Station. Quinn also helped it achieve membership in the AME Church's Western Circuit. Elisha Weaver began serving as the church's first full-time minister in 1850. The congregation adopted the name of Bethel AME Church in the late 1860s. [2] [3] Although the congregation continued to expand into larger buildings and extend its outreach programs to the area's African American community, it faced financial challenges throughout its early history. [4]

Georgia Street church

In 1841 the congregation had its first church built on Georgia Street between the Central Canal and Mississippi Street (present-day Senate Avenue). [5] The Bethel AME congregation continued to use the small, frame structure until 1857, when it bought the first Christ Church building from the city's Episcopal congregation. (The Episcopal parishioners had decided to replace their wood-frame church with a new stone structure on its site on Monument Circle.) The AME congregation had the small church moved to their site on Georgia Street; however, the church was destroyed by fire in 1862. [6] [7] It is believed that the AME congregation's open support of the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad, which provided protection to slaves en route to Canada, may have led some pro-slavery advocates to burn the church. [3] The congregation raised funds and had the frame church rebuilt in 1867. The replacement structure served the congregation until its brick church on West Vermont Street was built in 1868–69. [5] The congregation sold a lot it owned at the corner of Michigan and Tennessee Streets (present-day Capitol Avenue) for $3,000 and used the funds to purchase another lot for $5,000 on West Vermont Street that served as the site for the new church. [1]

Vermont Street church

The church's West Vermont Street site, located in the northwest section of downtown Indianapolis, has historically been the heart of the African American community. The neighborhood included a mix of residential, retail, commercial, and light industry. [1] [2] In 1867 the congregation contracted with Adam Busch to build a new brick church on its West Vermont Street lot. The church was supposed to have cost $10,400. By 1869, when the building was only partially completed, the congregation moved into the new church at 414 West Vermont Street and adopted the name of Bethel AME Church. [5] [8] Bethel congregation sold or mortgaged other property it owned to complete construction of the church. The church was sold on July 24, 1880, to pay off its debts, but its new owner allowed the congregation to repurchase the property in 1891 when sufficient funds had been raised to pay off a mortgage. Subsequent mortgages on the church were paid off in 1944, 1961, and 1982. [9]

Post- World War II development and the declining nearby neighborhood caused the area to change, but the Bethel AME congregation remained in its aging church, which was renovated in 1974 in order to make more space for outreach activities. Eventually, urban development dominated the surrounding area, which included hotels, apartments, museums, and office space along the Central Canal to the east, north, and south. The sprawling IUPUI campus was established west of the church. [1] [2]

Bethel AME Church was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1991; at that time it was the only African-American church building in Indianapolis to receive that recognition. [2] The state historical marker for Bethel AME Church, which is located across from the building on West Vermont Street, was dedicated on June 20, 2009, to commemorate the site that Indianapolis's oldest African-American church had occupied since 1869. [10] [11]

Sale and future development

In 2015 the Bethel AME congregation initiated a capital campaign to raise the $2 million to $3 million needed to repair the deteriorating building, but it proved to be unsuccessful. Without the major funding needed to proceed with the church repairs, the congregation began considering offers to buy the Vermont Street property. In early 2016 the congregation reached an agreement with SUN Development and Management Corporation, an Indianapolis-based developer, to sell the property for an undisclosed amount and relocate. SUN Development, who agreed to preserve as much of the structure as possible, planned to build a hotel on the property. Under the terms of the sale, the congregation had to vacate the property by August 2016. [12] [13]

In February 2017 Indiana University announced that its School of Informatics and Computing at IUPUI had received a grant from the university to create a three-dimensional virtual reality model of the historic Vermont Street church. IUPUI students collected 3,000 images for use in the modeling project. When completed, the model will be accessible to the public through IUPUI's School of Informatics and Computing. Digital images used to create the model will be housed at the IUPUI Library; the digitized archive, along with other archival records from the church, will be held in collection of the Indiana Historical Society in Indianapolis. [14]

In 2018, the congregation' opened a new church building on Zionsville Road in Pike Township in northwest Indianapolis. [15]

Building description

The Vermont Street site originally consisted of a three-story church and an adjacent two-story parsonage that connected to the main building by an enclosed passageway. The church and parsonage date from 1867 to 1869; the parsonage was converted to a church office at a later date. The church's four-story tower, east gable, and west cross gable were added as part of a major renovation to the church in 1894. A false façade of metal framework and stucco was added to the church's and parsonage's south façade in 1973–74. The church's original brick façade and its main entrance was partially obscured by the 1974 update; however, the building retained many features dating to its construction in 1869 and the renovation in 1894. [1] [16]

Exterior and plan

The three-story church and its square, four-story tower were constructed of red brick over a limestone foundation and contained some Romanesque Revival features. [16] Only the northeast corner of the tower was attached to the church. The tower had paired windows on the second story, multiple round arches above the third-floor windows, and a round arch flanked by pairs of pilasters at the fourth-story level. The tower's hip roof was topped with a cross finial. [1]

The church's main entrance, facing south toward Vermont Street, had a false façade of stucco that included a single arch over the main entrance and two narrow arches on either side. [16] [17] The church's east elevation, partially obscured by the adjacent parsonage, had a cross-gabled section with tall, round-arched windows and two-story arched windows that divided into two lancets at the second-story level. The church's west elevation had vertically-aligned window openings and one doorway on the south. (Another door on the north of this elevation was enclosed.) The west elevation's second and third stories each had five, round-arched windows; its cross gable had a lunette window. The north (rear) elevation had a gabled section with two arched windows on the first story, one round-arched window on the second story, and two round-arched windows on the third floor. A hip-roofed section at the rear had an arched doorway and a window on the ground floor with a two-story arched window that divided into two round-arched lancet windows above. The rear elevation also had an exterior chimney. [1]

An adjacent, two-story parsonage east of the church was erected at the time of the church's initial construction (1867–69). The red brick parsonage connected to the church on the first and second floor and was later converted to a church office. Its gable front (the main façade facing Vermont Street) was covered with a false façade in 1974. Openings in the south façade were blocked in, probably when the false façade was added. A gable-roof porch covered the parsonage's main entry. Originally, the south elevation had arched openings with a door and two windows on the first floor and three windows on the second floor. The east elevation had a two-story gabled main section and a shed-roofed section in the rear. The main section had two windows on the first floor, one on the second; the shed-roof section had one window. [1]

Interior

The church's cube-shaped interior included a sanctuary and meeting rooms; its tower housed a staircase. The church had two entrances, one on its south elevation facing Vermont Street and another in the tower. A narrow lobby across the main building had doors in the north side that lead to a meeting room. Smaller rooms were established along the west wall. The lower level included a kitchen. The main stairway to the second-floor sanctuary was accessed from the east side of the first-floor lobby. [1]

The sanctuary was remodeled in 1894 to a two-story space with the altar on the east wall. A balcony along the west wall was accessible from staircases in the sanctuary's southeast and northwest corners. Auditorium-style seating faced the altar. (This arrangement altered the original plan, which may have placed rows of pews facing an altar located on either the north or south wall.) Two tiers of windows on the west and north walls lighted the sanctuary; tall windows lit the altar. The coved ceiling was covered with beaded wood board and had a square coffer at the center. [1]

Later changes to the building included enlarging its choir loft, installation of a pipe organ and stained-glass windows, and updates to the building's heating, lighting, and electrical systems. [16] [9] The church's hand-carved pulpit was a gift from Reverend Andre Chambers in honor of his wife, Lettie. [18] In 1961 pastor C. T. H. Watkins and architect Walter Exxell redesigned the church's chancel. [18] The congregation also renovated the church building and adjoining parsonage in 1974. [2] Window openings in the sanctuary's south wall were covered over and the related woodwork was removed due to the addition of the false façade on the exterior. [1]

The front door of the parsonage/church office led to a side staircase and hall. A first-floor room was converted to an office. In addition, smaller rooms or offices were made on the parsonage's first and second floors. [1]

Mission

The Bethel AME Church elevated its role in the community as the city's black population increased. [2] [4] Indianapolis's African American population was small during the early decades of the nineteenth century. In 1840, shortly after the congregation organized, only 195 blacks lived in the city. [19] Before the American Civil War, the congregation became active in the antislavery movement and supported the Underground Railroad. [3] At that time Indianapolis's black population comprised less than three percent of the city's total population. In 1860, when Indiana's statewide population reached 1,338,710, its African American population was 11,428. However, as the war progressed, the number of blacks coming to Indianapolis from the South and Indiana's rural areas continued to rise, nearly doubling the state's African American population by 1870, a few years after the Bethel AME church was erected on Vermont Street. By 1900, shortly after the church underwent a major renovation, African Americans comprised nearly ten percent of the city's population. [5] [19] [20]

Bethel, the city's only AME congregation for thirty years, became the mother church to several congregations of the African Methodist Episcopal churches in Indiana, [3] including the Allen Chapel, Coppin Chapel, Saint John, and Wallace (Providence) congregations. [21] The Bethel congregation also served in the development of the AME church. In 1854, 1859, and 1864, Bethel hosted the denomination's annual conference. [2] [22] In addition, it hosted an AME bishop's conference and a general conference in 1888. [9]

Education was also an important mission of the church. The congregation established its first school for African American children at the church in 1858. (Before the mid-1870s, Indianapolis's public schools did not allow African American children to enroll.) Later, the congregation operated a kindergarten at the church and a day school. [3] [5]

The Bethel church also became a public meeting place for social activism, as well as a venue for organizing and implementing social services including providing money, clothing, and temporary lodging to African Americans immigrating to the city from the South after the Civil War. [23] Over the years the church provided other social programs such as a credit union, counseling services, a well-baby clinic, and day-care services for children and adults. [21] The church also served as a venue for organizing local associations that were instrumental in achieving better housing, education, and equal rights for African Americans. Local chapters of several organizations were created at Bethel, including the Indianapolis chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People in the early 1900s and the Indiana State Federation of Colored Woman's Clubs on April 27, 1904. [3] [11] [24]

During the twentieth century, Bethel AME Church continued to support the city's black community living northwest of the downtown area. The congregation operated a food pantry, youth and senior citizens programs, and clothing drives, among other activities. [1] Throughout civil rights activism of the mid-twentieth century, Bethel provided a space of racial solidarity and continued its long tradition of offering community outreach services to the city's African Americans. [2] [25] In 2013 the church became a member of the Indianapolis Congregation Action Network (IndyCan) and has served as headquarters for the network's Mass Transit Campaign. [26]

Membership

The congregation began in 1836 with a few members meeting in a log cabin. By 1848 the small group had grown to 100 members and was meeting in a small frame church on Georgia Street. [3] In the early 1860s, before the congregation expanded to the large brick church on West Vermont Street, the church's membership reached 120. [27] Over the next century the membership continued to increase. By the early 1990s the congregation had an estimated 1,200 members; [2] however, its membership declined in subsequent decades. The congregation's membership was estimated at 120 to 150 when the West Vermont Street property was sold in 2016. [12] [13]

Notable members

- Reverend Willis Revels, a pastor at Bethel AME Church in the 1860s, encouraged African Americans to enlist in the Union army during the American Civil War [27] [28]

- Doctor Samuel Elbert, a physician, was the first African American graduate of the Medical College of Indianapolis and served as the secretary of the Indiana Board of Health [5]

- Madam C. J. Walker, a prominent African American hair care and beauty products entrepreneur, who was also philanthropist and activist in the early twentieth century [5]

- Doctor Joseph Ward, an Indianapolis physician, served as director of the Tuskegee Veterans Administration Medical Center at Tuskegee, Alabama [5]

- Mercer Mance was Indiana's first elected African American judge [5]

Notes

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Michelle D. Hale, "Bethel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church," in David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, ed. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana University Press. pp. 318–19. ISBN 0-253-31222-1.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Aboard the Underground Railroad, Bethel A.M.E. Church". National Park Service. Retrieved 31 July 2015.

- ^ a b Stanley Warren (Summer 2007). "The Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 19 (3). Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Society: 32. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i The History of Nine Urban Churches. Indianapolis, IN: The Riley-Lockerbie Ministerial Association of Downtown Indianapolis.

- ^ Most secondary sources report that the fire destroyed the AME congregation's Georgia Street church in 1862; however, Warren, p. 33, says it occurred in July 1864.

- ^ The Christ Church building that the Bethel AME congregation purchased in 1857 was constructed on the Circle in 1838. The Gothic Revival-style structure was painted white and measured 29 feet (8.8 m) by 43 feet (13 m). It had a total seating capacity of 350 people. See Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 413. See also: Carl R. Stockton (1987). Christ Church in Indianapolis: A Selected Chronology. Indianapolis, Indiana: C. R. Stockton. pp. 3–5. See also: Eli Lilly (1957). History of the Little Church on the Circle: Christ Church Parish, Indianapolis, 1837–1955. Indianapolis, Indianapolis: Rector Wardens and Vestrymen of Christ Protestant Episcopal Church. pp. 52–54, 127.

- ^ "Forged Through Fire: Bethel AME Church, Indianapolis Station AME Church, 1836-1869". Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ a b c Warren, pp. 34–35.

- ^ "June 20, 2009–Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ a b "Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ^ a b Kelly Patrick Slone (April 21, 2016). "Historic Bethel AME Church Sold for Hotel Project". Indianapolis Recorder. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ a b Olivia Lewis (August 22, 2015). "Bethel AME Fights to Keep Legacy Alive". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017. See also: Olivia Lewis (April 11, 2016). "Indy's Oldest African-American Church sold for Hotel Space". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "IUPUI Newsroom: IUPUI Faculty Use Grant to Help Digitally Preserve Historic Indianapolis African-American Church". Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. February 15, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- ^ "Church History". Bethel Cathedral AME Church. Retrieved April 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d "Bethel AME Church, Indianapolis (Marion County)" (PDF). Travels in Time: African American Sites. Indiana Department of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

- ^ The church's original south façade, now covered, had three openings on its upper and lower portions. The main entrance had a large, round arch. A gabled dormer with a large, round arched window was centered above the entry; however, it was removed as part of the 1973 alteration to the south façade. See "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ a b The Art and Architecture of Nine Urban Churches. Indianapolis, Indiana: The Riley-Lockerbie Ministerial Association of Downtown Indianapolis.

- ^ a b M. Teresa Baer (2012). Indianapolis: A City of Immigrants. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-87195-299-8.

- ^ Emma Lou Thornbrough, "African-Americans," in David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, ed. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. pp. 5–14.

- ^ a b Warren, pp. 33, 35.

- ^ Warren, pp. 32, 33, 34.

- ^ "Colored Immigrants in Indiana: Their Character and Location". The Indianapolis Leader: 1–2. January 24, 1880. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ "Above the Underground Railroad: Bethel AME Church". National Park Service. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- ^ Bethel A.M.E. Church, Indianapolis, Indiana. Interviews by Melissa Burlock, 18–21 July 2013. Audio recordings, IUPUI Special Collections and Archives, e-Archives, https://archives.iupui.edu/handle/2450/6956/browse?type=dateissued.

-

^ Carey A. Grady, Senior Pastor of Bethel A.M.E. Church. Phone conversation with writer, 14 July 2014. See also:

"IndyCAN heralds mass transit bill passage". NUVO. Indianapoliis, Indiana. Retrieved July 14, 2014. See also:

"Archived copy". Archived from

the original on 2014-07-18. Retrieved 2014-07-15.

{{ cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title ( link) - ^ a b Warren, p. 33.

- ^ Bodenhamer and Barrows, eds., p. 1191.

References

- "Aboard the Underground Railroad, Bethel A.M.E. Church". National Park Service. Retrieved July 31, 2015.

- The Art and Architecture of Nine Urban Churches. Indianapolis, Indiana: The Riley-Lockerbie Ministerial Association of Downtown Indianapolis.

- Baer, M. Teresa (2012). Indianapolis: A City of Immigrants. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-87195-299-8.

- "Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- "Bethel A.M.E. Church, Indianapolis, Indiana: Interviews by Melissa Burlock, July 18–21, 2013" (audio recording). IUPUI Special Collections and Archives, e-Archives.

- "Bethel AME Church, Indianapolis (Marion County)" (PDF). Travels in Time: African American Sites. Indiana Department of Historic Preservation and Archaeology. Retrieved July 28, 2017.

-

"Bethel Cathedral (Archived copy)". Archived from

the original on July 18, 2014. Retrieved July 15, 2014.* Bodenhamer, David J., and Robert G. Barrows, eds. (1994). The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis. Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press.

ISBN

0-253-31222-1.

{{ cite book}}:|author=has generic name ( help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list ( link) - "Colored Immigrants in Indiana: Their Character and Location". The Indianapolis Leader. Indianapolis, Indiana: 1–2. January 24, 1880. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- "Forged Through Fire: Bethel AME Church, Indianapolis Station AME Church, 1836-1869". Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- The History of Nine Urban Churches. Indianapolis, IN: The Riley-Lockerbie Ministerial Association of Downtown Indianapolis.

- "IndyCAN heralds mass transit bill passage". NUVO. Indianapoliis, Indiana. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- "IUPUI Newsroom: IUPUI Faculty Use Grant to Help Digitally Preserve Historic Indianapolis African-American Church". Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis. February 15, 2017. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- "June 20, 2009 –Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Indiana Historical Bureau. June 20, 2009. Retrieved July 8, 2014.

- Lewis, Olivia (August 22, 2015). "Bethel AME Fights to Keep Legacy Alive". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Lewis, Olivia (April 11, 2016). "Indy's Oldest African-American Church sold for Hotel Space". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Lilly, Eli (1957). History of the Little Church on the Circle: Christ Church Parish, Indianapolis, 1837–1955. Indianapolis, Indianapolis: Rector Wardens and Vestrymen of Christ Protestant Episcopal Church.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Slone, Kelly Patrick (April 21, 2016). "Historic Bethel AME Church Sold for Hotel Project". Indianapolis Recorder. Indianapolis, Indiana. Retrieved July 31, 2017.

- Stockton, Carl R. (1987). Christ Church in Indianapolis: A Selected Chronology. Indianapolis, Indiana: C. R. Stockton.

- Warren, Stanley (Summer 2007). "The Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church". Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. 19 (3). Indianapolis, Indiana: Indiana Historical Society: 32. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- "Welcome to Bethel AME Church". Bethel AME Church. Archived from the original on August 25, 2017. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

External links

- Bethel AME Church Timeline

- "Bethel A.M.E. Church Records, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1922–2015" Collection Guide, Indiana Historical Society

- "Bethel A.M.E. Church Addition 1871–2016" Collection Guide, Indiana Historical Society

- "Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (Indpls.) Board Minutes, 1871–1909" Collection Guide, Indiana Historical Society

- "Bethel A.M.E. Church (Indianapolis, Ind.) Sunday School Records" Collection Guide, Indiana Historical Society

- African-American history of Indianapolis

- African Methodist Episcopal churches in Indiana

- Churches on the National Register of Historic Places in Indiana

- Romanesque Revival church buildings in Indiana

- Churches completed in 1869

- Churches in Indianapolis

- 1869 establishments in Indiana

- National Register of Historic Places in Indianapolis